Girl, You’ll Be a Woman Soon

As the seven-and-a-half-year cycle of page-a-day ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study comes to a close, the ancient rabbis discuss when adolescence ends and compare female sexual maturity to ripening figs

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

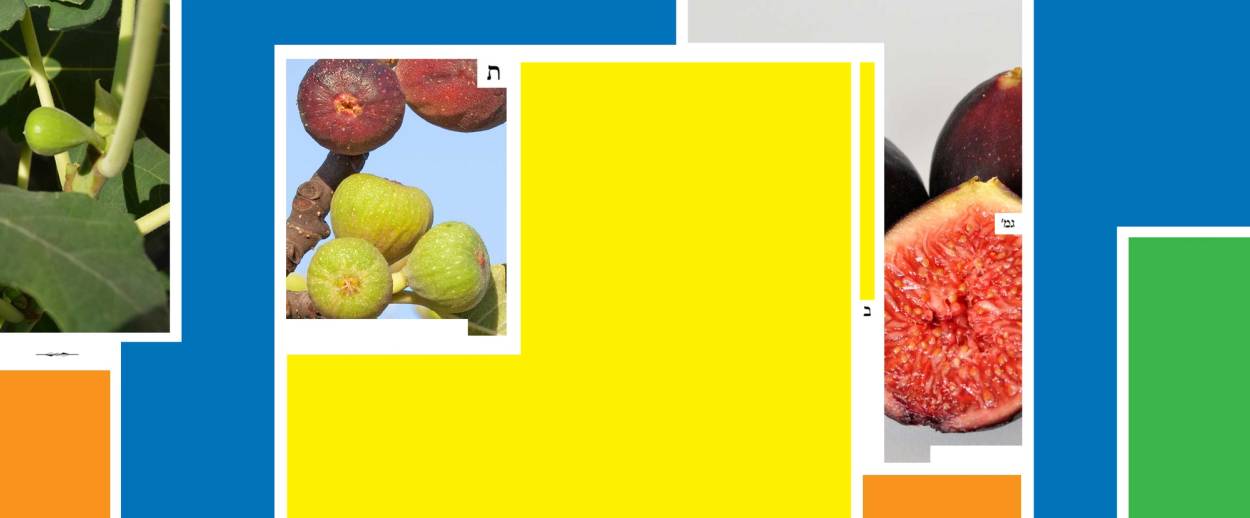

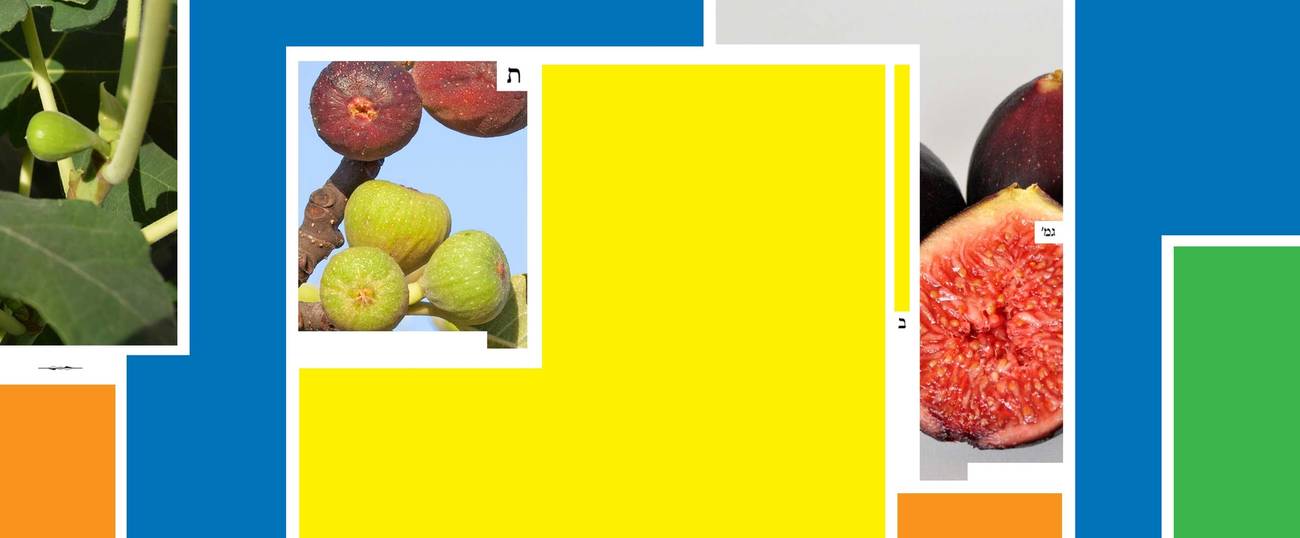

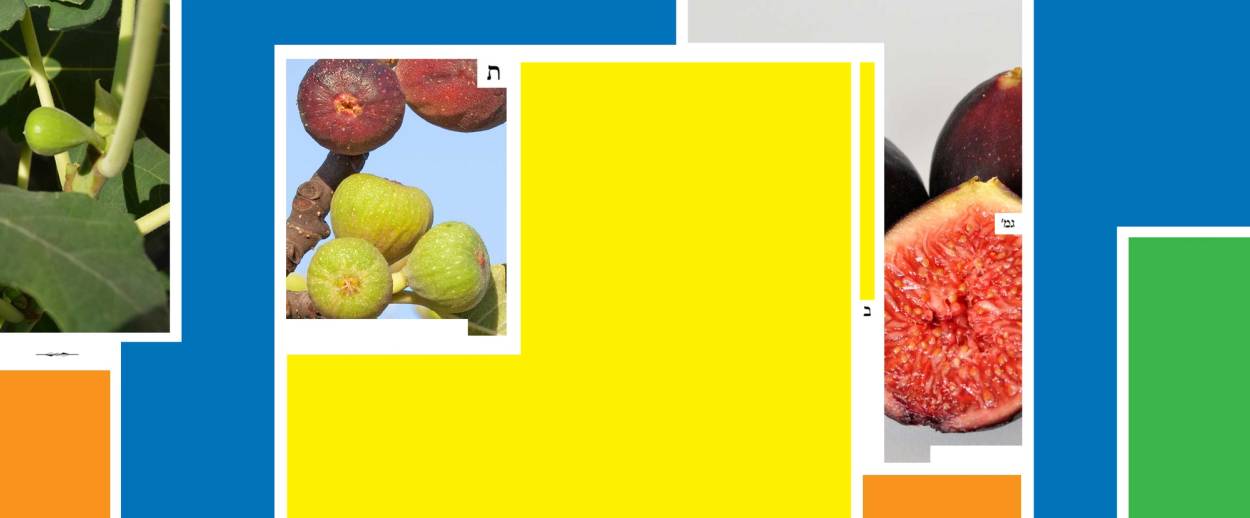

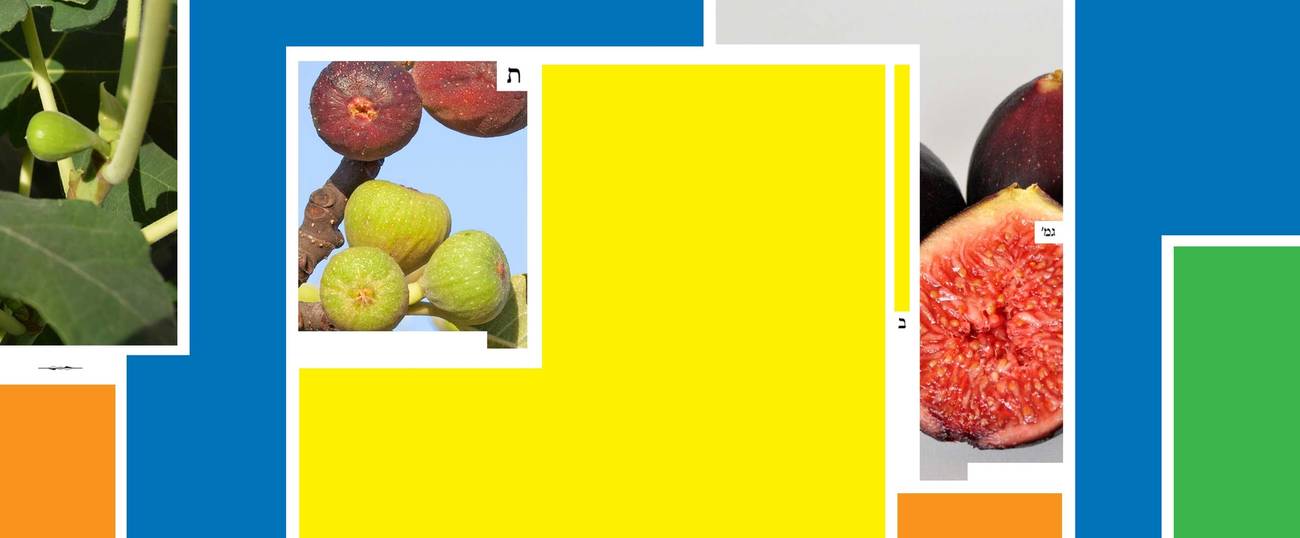

Each volume of the Koren Talmud Bavli comes in a dust jacket that bears an image related to its contents. Avoda Zara, about idol worship, features a marble bust of a Greek god; Menachot, about meal offerings, has an illustration of a sacred vessel full of flour. So I was curious, as Tractate Nidda approached, how the publishers would choose to illustrate a volume whose main subject is menstrual blood. Their clever solution was to use an image of figs, for reasons that Daf Yomi readers discovered in last week’s reading.

In the mishna on Nidda 47a, the sages offer a “parable” comparing the development of a woman to the growth of a fig tree: A girl is like an “unripe fig,” a young woman is like a “ripening fig,” and an adult is like a “ripe fig.” For the rabbis, this metaphor is meant to clarify practical legal issues about how the rights and responsibilities of a woman change as she gets older. Not all of these issues pertain to menstruation, but it makes sense that they are discussed in Tractate Nidda, since menstruation is an indicator of puberty. And puberty, for boys as well as girls, is the key dividing line between minors, who are not halachically responsible for their words and actions, and adults, who are.

As a child, a girl is under the legal control of her father, which means that he owns any object she finds or any wages she earns. As we saw much earlier in the Daf Yomi cycle, in Tractate Nedarim, a father also has the power to nullify a minor child’s vows to God—promises to avoid eating certain foods, for instance, or not to cut her hair. There is a similar principle in American law, where a minor can’t enter into a contract.

But while American law defines minority in simple chronological terms—in most states, you become a legal adult at age 18—things are more complicated in the Talmud. To become a legal adult in Jewish law, a boy must be 13 years old and have grown two pubic hairs, while a girl must be 12 years old and have grown two pubic hairs. Obviously it’s not the possession of hair itself that matters; rather, this is a sign of the beginning of puberty, which is supposed to bring greater mental and emotional maturity. That is why the ages are different for boys and girls: According to Yehuda HaNasi, “the Holy One, Blessed be He, granted a woman a greater understanding than a man,” so she attains mental maturity sooner. (Rav Shmuel bar Yitzhak dissents from this view, however, arguing that since boys study Torah and girls don’t—at least, they didn’t in talmudic times—“cleverness enters” boys’ minds earlier.)

But if a young girl is an unripe fig and a girl older than 12 is a ripe one, who is what the Talmud calls a “ripening fig”? The answer comes in Nidda 45b, where the mishna explains that for both girls and boys, there is a transitional phase between childhood and adulthood. This period begins one year before the age of majority—at 11 for girls and at 12 for boys—and involves a special relationship to vows. (In general, the rabbis strongly discourage the taking of vows, since they create an opportunity for an unnecessary sin.)

The vows of children are legally invalid, even if they claim to know exactly what they are doing: “Even if they said: We know in Whose name we vowed … their vow is not a vow.” After the age of majority, on the other hand, a person’s vows are binding even if he claims not to have fully understood the significance of vowing: “even if they said: We do not know in Whose name we vowed … their vow is a vow.” But during the transitional year, the validity of a minor’s vow is decided on a case-by-case basis. They must be “examined” by a sage to determine whether they understand what it means to take a vow to God. This is in keeping with Numbers 6:2, which says, “when a man or a woman shall clearly utter a vow”: Only if a minor understands the full meaning of the vow does it count as “clearly uttered.”

This transitional period acknowledges the possibility that a child who is on the cusp of adulthood might be what the Talmud calls “discriminating.” But it also creates a problem for the legal definition of adulthood, which involves both chronological and biological milestones. Ordinarily, even if a girl under the age of 12 or a boy under the age of 13 develops two pubic hairs, they do not become legal adults, because these are not considered to be true pubic hairs. Rather, they are treated like “hairs that grow on a mole,” which can appear before the onset of puberty.

But what if someone grows two pubic hairs during the year when they are a discriminating minor? If they are mentally mature enough to take vows and physically mature enough to show signs of puberty, why shouldn’t they become legal adults even before the age of 12 or 13? This is a matter of dispute among the rabbis: Rabbi Yochanan says that if a discriminating minor grows pubic hairs, they ought to be punished for their sins like an adult, but Rabbi Zeira disagrees, and it is his view that prevails.

Another problem arises when the rabbis ask about the signs of puberty in girls. Ordinarily, puberty is defined by what the rabbis call “the signs below”—the growth of two pubic hairs. But women, unlike men, also have “the signs above”—the development of breasts. This is defined differently by different sages—for instance, when “a fold appears below the breast,” or when “the areola darkens.” The question then arises whether it’s possible for a girl to possess the upper signs without the lower signs, and if so, which should determine whether she is a legal adult. After some debate, the rabbis finally decide that it is impossible for a girl to develop breasts before she grows pubic hair. If that appears to be the case, we read in the Gemara in Nidda 48b, it can only be because the hairs “appeared but later they fell out.”

Who is responsible for ascertaining whether a girl has grown two pubic hairs? The rabbis never consider trusting a girl’s own report, and one might assume that she must submit to the examination of a sage—just as the sages are the ones who examine blood-stained clothes to determine if a woman is menstruating. But the idea of adult men examining the bodies of young women would obviously go against talmudic sexual morality, which is based on preserving the modesty of women and avoiding the temptation of men.

Accordingly, the Gemara states that the determination of whether a girl has pubic hair is made “based on the testimony of women.” Some sages would entrust this task to their own female relatives: “Rabbi Eliezer would give the girls to his wife to examine, and Rabbi Yishmael would give the girls to his mother to examine.” This is a notable departure from usual halakhic practice, which requires the testimony of two male witnesses. But when patriarchal values collide, it seems, the rabbis are willing to suspend male authority in order to preserve female purity.

It feels strange to say this, but after seven and a half years, this is the next to last column in my series about Daf Yomi. The cycle concludes on Jan. 4 with the last page in Tractate Nidda, before starting all over again the next day with the first page of Berachot. Next month, in my final column, I will reflect on my long talmudic journey and on the Siyum HaShas, which will bring together 90,000 Jews to celebrate the Daf Yomi experience on New Year’s Day.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.