When the Talmud Replaced the Temple as the Structure at the Heart of Jewish Life

Judaism became a religion of laws, haunted and bound by the absence of a home for Jewish sovereignty

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

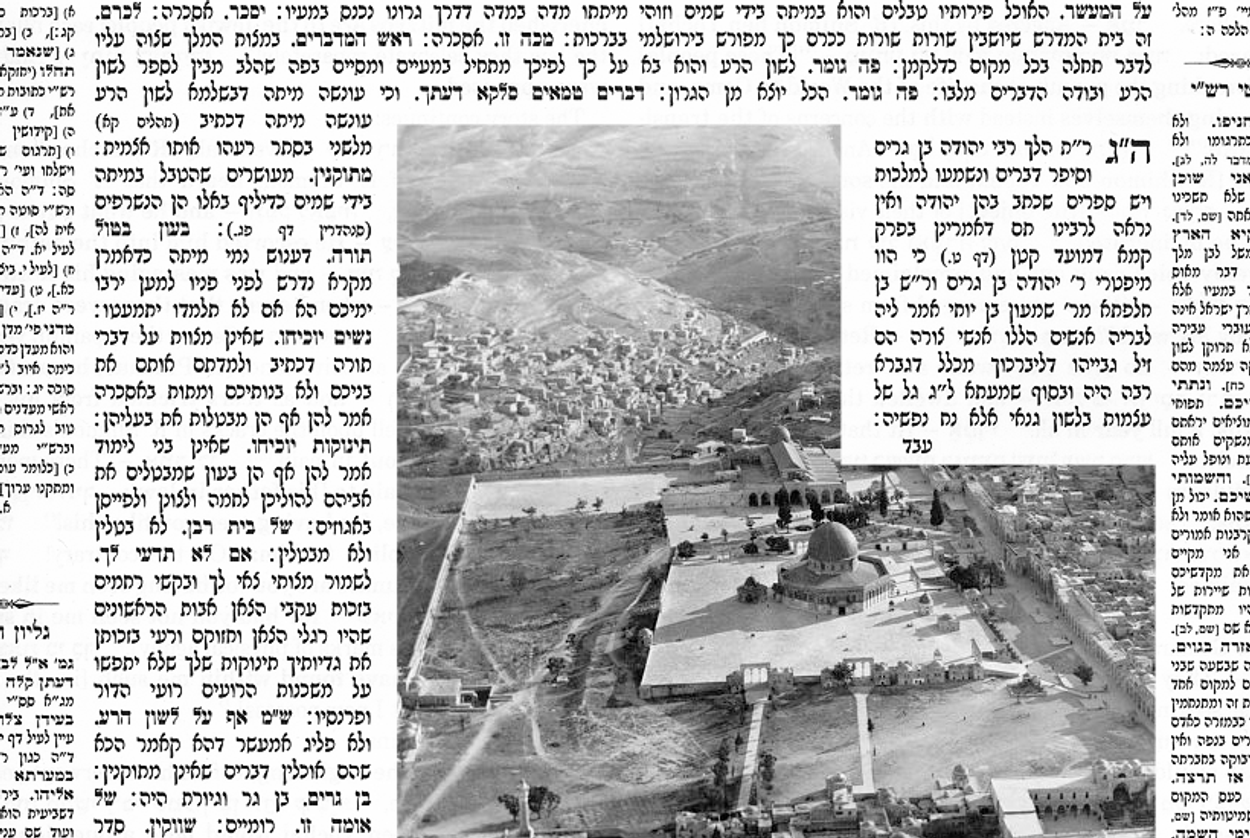

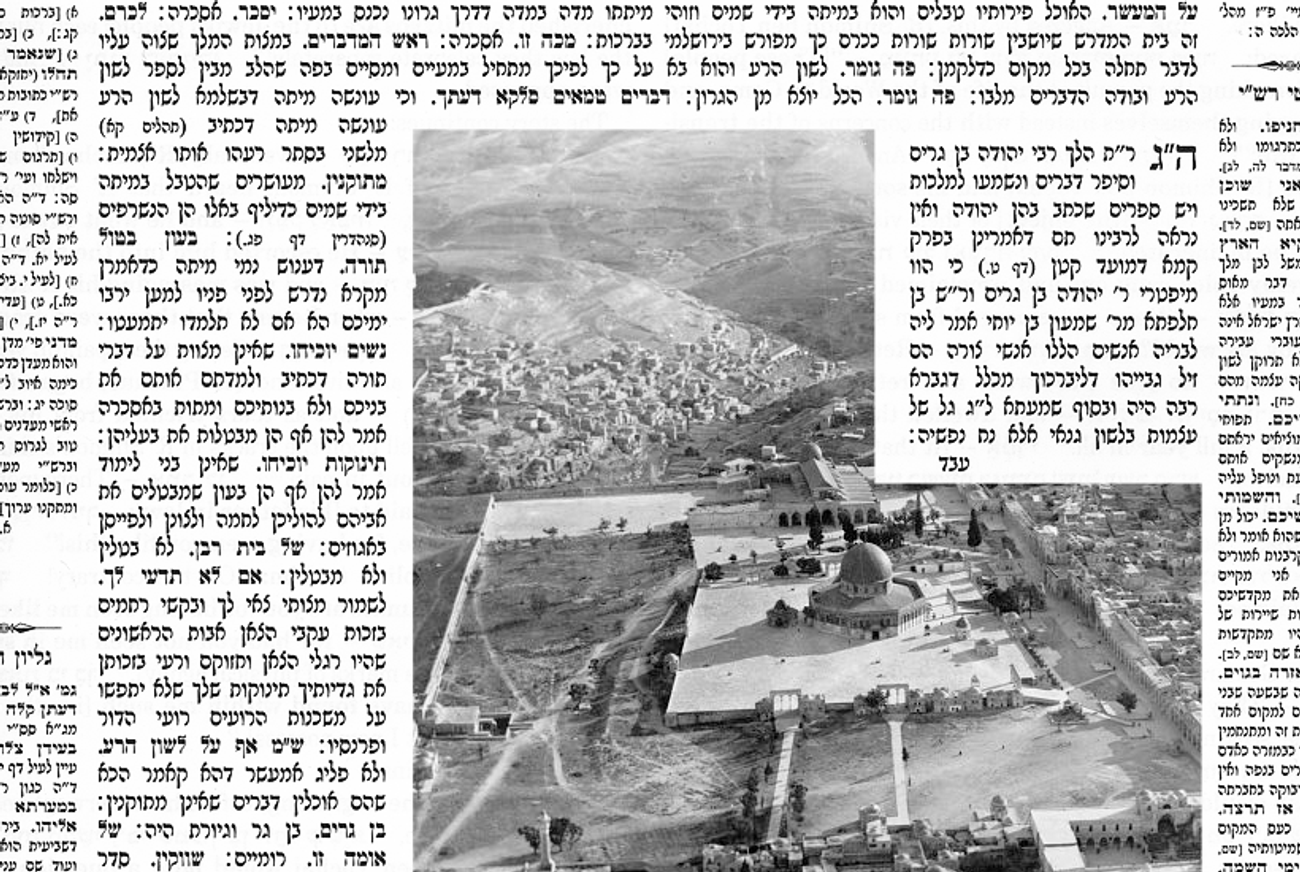

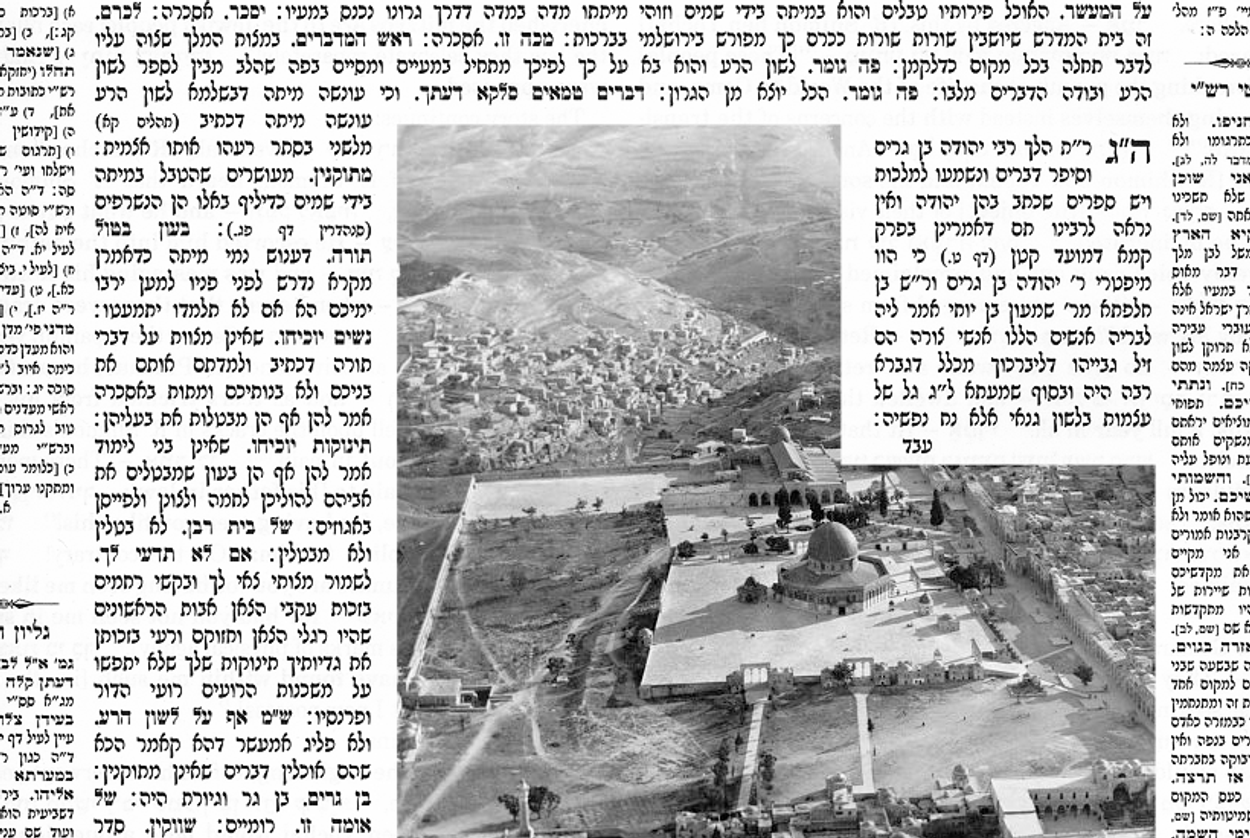

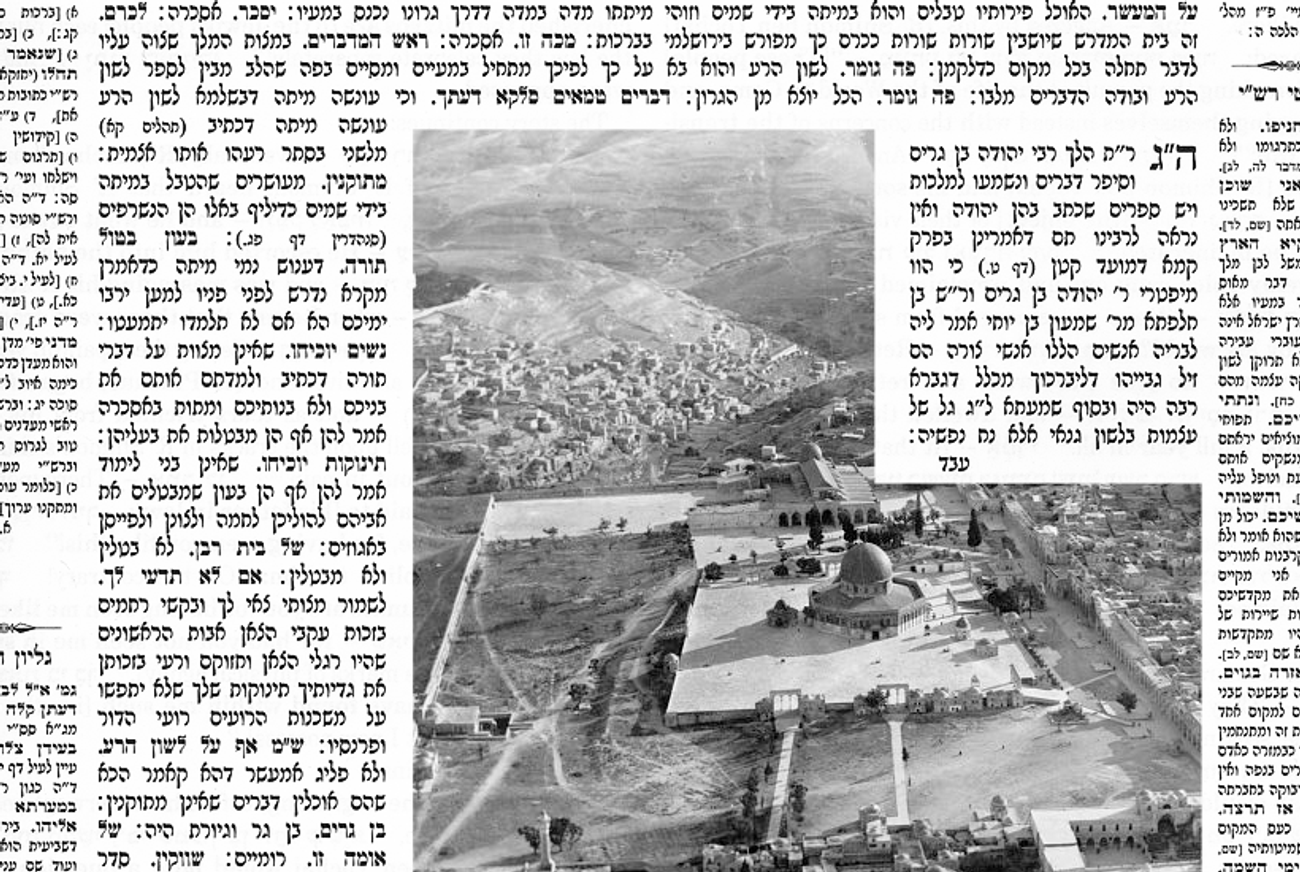

The destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E. might easily have meant the death of Judaism. As we have seen again and again in the Talmud, the Temple was the center of Jewish belief and practice in a way that we can hardly imagine today. It was the only place where Jews could sacrifice to God, the only place where God’s spirit dwelled on Earth—not to mention a powerful symbol of Jewish sovereignty. The fact that Judaism managed to survive after the Temple was burned to the ground is the most remarkable of the many acts of renewal and transformation that have preserved Jewish life over thousands of years.

The legend of Yochanan ben Zakkai is a vivid parable of how Judaism managed to endure that trauma. According to tradition, Yochanan, the leading rabbinic sage of his generation, was trapped in Jerusalem during the Roman siege. The historian Josephus describes this as a time of horrific suffering, when starvation led to infanticide and cannibalism. Yochanan, seeing which way the wind was blowing, decided that his duty was not to perish with the city but to escape. You could not simply walk out of besieged Jerusalem, however—not because of the Romans, but because the Jewish Zealots in charge of the city killed anyone who tried to go over to the enemy.

The dead, however, could be taken out of Jerusalem for burial. So, Yochanan pretended to be a corpse and had himself smuggled out of the city in a coffin. Once he made it to the Roman lines, he pleased the general Vespasian by prophesying that he would one day become emperor—a prediction that indeed came true. In exchange, Vespasian granted Yochanan’s request to set up a new Jewish academy and court in Yavneh. In this way, Yochanan and Judaism itself passed through death into a new, different kind of life. From then on, Judaism would no longer be a Temple-centered religion but a religion of laws. The Talmud itself would replace the Temple as the “structure” at the heart of Jewish life.

The absence of the Temple cannot help but haunt the Talmud, especially in Order Moed, the section that Daf Yomi readers have been exploring for the last two years. These tractates deal with the Jewish holidays, many of which used to be highly Temple-centric. Yom Kippur, for instance, was the occasion of an elaborately choreographed sacrificial ritual in which the high priest would atone for the people’s sins. Rosh Hashanah, too, had its special Temple practices. In Rosh Hashanah 29b, we learn that when the holiday fell on Shabbat, it was forbidden to blow the shofar; but an exception was made for the Temple, where it was allowed.

What was to be done, then, after the Temple’s destruction? Should Jews blow the shofar on Shabbat or not? As we learned in this week’s Daf Yomi reading, this was the subject of one of the nine decrees that Yochanan ben Zakkai issued after 70 C.E., in which he began to create a post-Temple Judaism. According to Yochanan, the court at Yavneh would take the Temple’s place for the purposes of shofar-blowing; and some other sages add that he authorized the shofar anyplace there was a Jewish court. This was a highly symbolic intervention, suggesting as it did that the court had taken the place of the Temple as a holy site, and that rabbis were stepping into the leadership role once held by priests.

As the Gemara goes on to explain, Yochanan faced some opposition to this new rule, which he cunningly disarmed. One year, when Rosh Hashanah fell on Shabbat, Yochanan proclaimed that the shofar should be sounded. But the “sons of Beteira”—members of an ancient family of sages—objected to this, saying, “Let us discuss whether or not this is permitted.” Yochanan replied by suggesting that they blow the shofar first, while there was still time, and then discuss the matter afterwards. Once the shofar had been blown, however, Yochanan presented his critics with a fait accompli: “He said to them: The horn has already been heard in Yavneh, and one does not refute a ruling after action has already been taken.” This bait-and-switch is a good example of a perennial problem in political philosophy—the lawlessness of the lawgiver. If you want to institute a new set of laws, as Yochanan did, you have to break with the existing laws; an act that is illegal when it is committed only then becomes a binding precedent. Yochanan, clearly, did not flinch from this responsibility.

Later in the chapter, the Talmud goes on to list the other new ordinances that Yochanan imposed after the Temple was destroyed. Traditionally, on Sukkot, the lulav was shaken on all seven days of the holiday only in the Temple, while Jews elsewhere shook it only on the first day. Yochanan decreed that from now on, all Jews should take the lulav for seven days, “in commemoration of the Temple.” “And from where do we derive that one performs actions in commemoration of the Temple?” the Gemara asks. The answer is a verse from Jeremiah: “For I will restore health to you, and I will heal you of your wounds, said the Lord; because they have called you an outcast: She is Zion, there is none who care for her.” Because there is “none who care” for the destroyed Temple, it is up to the Jews to show their care by commemorating it in actions.

Other decrees by Yochanan included changing the rules about when the new year’s crop could be eaten; how the Sanhedrin, the supreme Jewish court, should take testimony regarding the new moon; and a rule banning priests from wearing sandals on the bimah, presumably because this was injurious to their dignity. None of these, notably, are major ritual innovations. Yochanan did not take it upon himself to do anything as drastic as institute a new place for sacrifices, or a new Holy of Holies. He recognized that large and important parts of Jewish practice were nullified—or, as he would have said, suspended. For as we have seen before, and the Talmud repeats here during its discussion of the omer offering, the sages believed that someday the Temple would be miraculously restored, and all its laws would go back into force. That is one reason why the Talmud was needed—to remind the Jews of these laws and practices, which are always receding further into the past.

In the course of discussing Yochanan’s decrees, the Gemara offers a poignant fable about the exile of the Shekhinah, the Divine Presence, which paralleled the exile of the Jews themselves. While the Temple stood, it was the house of the Shekhinah, the physical location of God’s presence on Earth. But as the Jewish people became more and more sinful, the Shekhinah “traveled 10 journeys”—that is, it withdrew from the Temple in 10 stages. “From the ark cover to the cherub, and from one cherub to the other cherub, and from the second cherub to the threshold of the sanctuary; and from the threshold to the courtyard; and from the courtyard to the altar; and from the altar to the roof; and from the roof to the wall; and from the wall to the city; and from the city to a mountain; and from that mountain to the wilderness; and from the wilderness it ascended and rested in its place in Heaven.” You can sense the tender reluctance of the Shekhinah to leave her home and her people. At each stage, she might have turned back and come home, if only the Jews had mended their ways. Once God had departed, however, the destruction of his home was only a matter of time.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.