Why Early Jews Didn’t Care at All About Christians

In a struggle against the idea of history, Jewish life strives to change as little as possible, even when new religions take over

Literary criticAdam Kirschis readinga page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

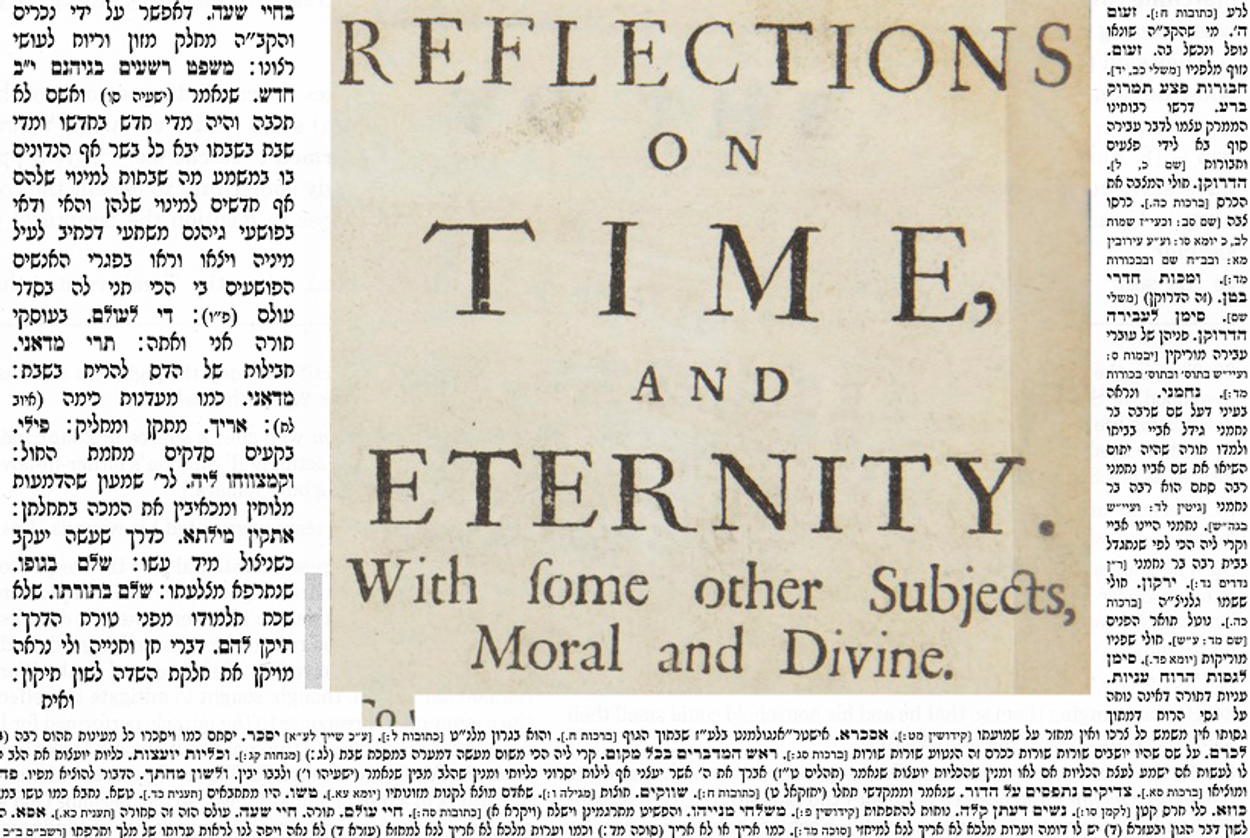

In this week’s Daf Yomi reading, the fourth and last chapter of Tractate Ta’anit, I was surprised to encounter a word that, as far as I can remember, has not previously appeared in two years of Talmud reading. That word is “Christians” (notzrim, derived from the name of Nazareth, Jesus’ home). My surprise came not from the fact that the rabbis of the Talmud recognized the existence of the rival faith, but from their ability to ignore it so completely for so long. After all, we hear regularly in the Talmud about the Romans, who ruled Palestine at the time the Talmud was being compiled, and occasionally about the Persians, who ruled Babylonia.

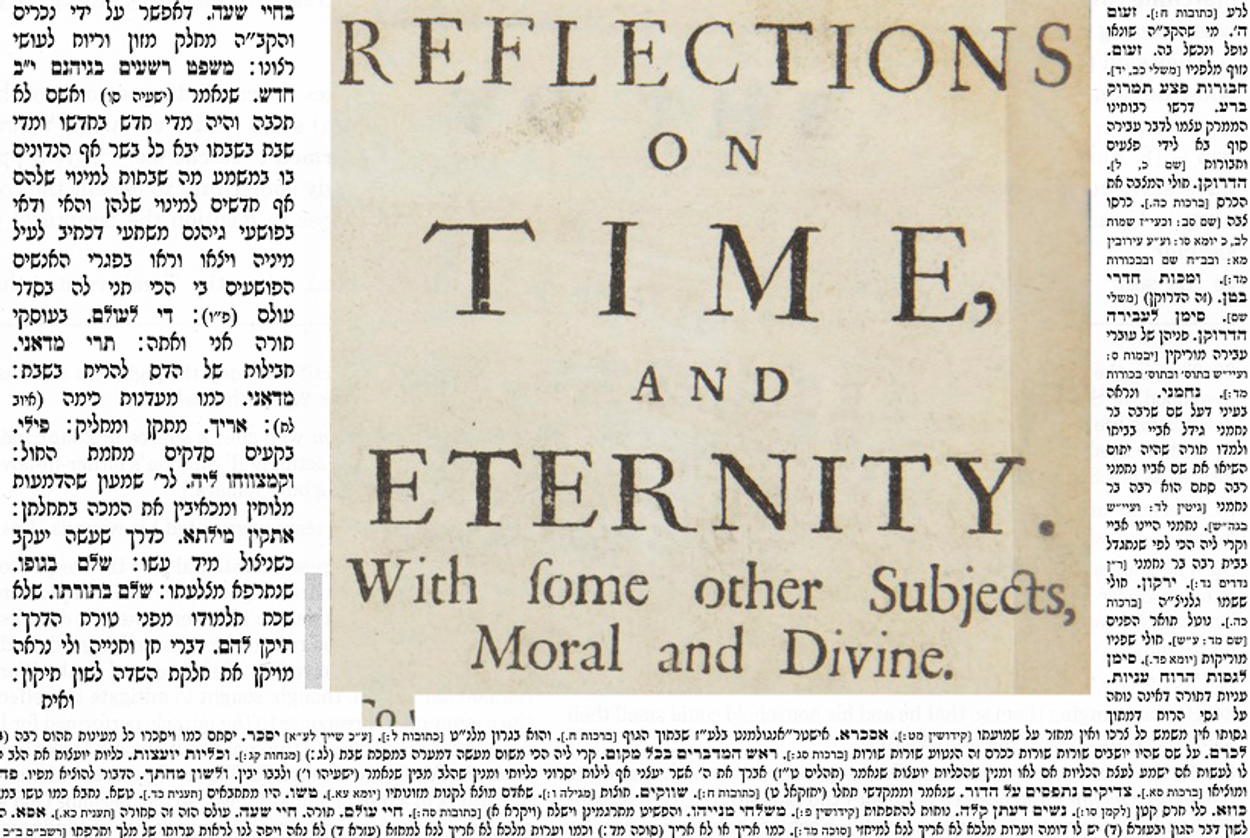

The era of the Talmud’s composition—the third to fifth centuries C.E.—was exactly the period when Christianity went from being a persecuted sect to the official religion of the Roman Empire, and the largest faith in the Near East. It would be natural to expect the rabbis to have something to say about this religion, which emerged out of Judaism and utterly transformed the world in which Jews lived. Indeed, it would be natural to assume that the Talmud itself was in some sense a response to Christianity—a way of defining Judaism as a religion of laws just at the moment when Christianity declared those laws to be obsolete.

Perhaps I will find as I continue to read the Talmud that there are indeed more references to Christianity; but so far, it has been conspicuous by its absence. The rabbis simply do not seem to feel that the existence of Christianity, its critique of Judaism, or its tremendous success in the world pose any real challenge to Judaism as they understand it. The point of rupture in Jewish history, as the rabbis see it, was not the birth of Jesus but the Temple’s destruction, which suddenly made much of Jewish ritual and practice impossible. And this rupture was, crucially, internal to Judaism—not a challenge from another belief system, but one that involves repairing and reinventing Jewish life to meet changed circumstances.

In Western culture, we tend to see Christian history as absolute history, and we learn about Jewish history largely in terms of its interactions with Christianity—whether that means persecution in the Crusades, or emancipation at the time of the French Revolution, or the failure of European assimilation in the 20th century. One reason I find it so illuminating to read the Talmud is that it presents an autonomously Jewish understanding of the world, in which Jews act rather than react. Indeed, the Talmud might even be said to struggle against the whole idea of history. Seder Mo’ed seems to inhabit a timeless time of ritual repetition, during which Jewish life strives to change as little as possible, keeping itself ready for the arrival of redemption.

The reference to Christianity in Ta’anit 27b comes during a discussion of fasting, which is this tractate’s main subject. In earlier chapters, we have heard about the procedures for fasting in response to drought and other calamities. Yet there are also certain fast days that are fixtures on the Jewish calendar, and the last chapter of Ta’anit explains their rationale. Some of these fasts remain central to Jewish practice—the 9th of Av, and to a lesser extent the 17th of Tammuz, which falls today, in a rare coincidence of the Daf Yomi calendar with the Jewish calendar. But the Talmud begins by talking about a whole category of fasts that disappeared from post-Temple Judaism: the fast of the “non-priestly watches.”

The priests who served in the Temple were divided into 24 “watches” or shifts, each the responsibility of a certain priestly family. (The Koren Talmud lists the names of these families, which were preserved in Jewish memory long after the Temple fell.) We’ve heard about these watches in earlier tractates; but now we learn that each of them had a corresponding watch made up of Israelites, common Jews who didn’t belong to the castes of Kohanim or Levites. These people served as representatives of the people at large, witnessing the sacrifices that were brought in the name of the whole Jewish nation. When a priestly watch was serving in Jerusalem, some members of the corresponding non-priestly watch would accompany them, while other members stayed home and read specified Torah portions.

From Monday to Thursday, the non-priestly watch would fast, and each day, the Gemara explains, was devoted to a specific worthy cause. “On Monday they would fast for seafarers,” because God created the sea on the first Monday of Creation; “on Tuesday for those who walk in the desert,” because the dry land was created on Tuesday; on Wednesday “over croup, that it should not befall the children”; and on Thursday “for pregnant women and nursing women.” Friday they would break the fast to prepare for Shabbat, and of course they would not fast on Shabbat itself. But what about Sunday—why didn’t the non-priestly watches fast that day?

“Due to the Christians,” Rabbi Yochanan explains, with enigmatic concision. This could either mean that the Jews did not want to appear to be observing Sunday as the Christian Sabbath, or that they were afraid to anger the Christians by appropriating their holy day. In either case, this precaution reveals that the Jews of Talmudic times were well aware of their Christian neighbors and of at least some of the practices of Christianity. Other rabbis, however, have very different explanations for the refusal to fast on Sunday. To Reish Lakish, this was “due to the added soul.” On Shabbat, Judaism has long believed, Jews are endowed with an extra soul, as a sign of the day’s holiness. At the close of Shabbat this soul departs, and Reish Lakish imagines that on Sunday Jews are convalescents, still recovering from the loss. It would be dangerous for them to fast in this weakened state.

Soon the Gemara turns to the fixed fast days, the 9th of Av and the 17th of Tammuz, and explains why they are so terrible in Jewish memory. We have already seen, in Tractate Rosh Hashanah, that the rabbis like to imagine many important events in Jewish history all taking place on the same date. Such coincidences are signs that history is not random but follows a predetermined course. How else could it be that the First Temple was destroyed by Nebuchadnezzar on the 9th of Av, and then, 500 years later, the Second Temple was destroyed by Titus on the same date?

And if the dates need a little massaging to line up, the rabbis aren’t bothered. The Book of Kings actually says that the First Temple was burned down on the 7th of Av, and Jeremiah says it happened on the 10th. How to reconcile these dates with each other, and with the traditional date of the 9th? The rabbis explain: On the 7th “gentiles entered the sanctuary,” on the 8th they desecrated it, on the 9th they set fire to it, and on the 10th it burned down completely. Any of these dates could conceivably have been chosen as the official anniversary, and indeed Rabbi Yochanan says, “Had I been alive in that generation, I would have established the fast only on the tenth of Av, because most of the sanctuary was burned on that day.” But the sages hold that “it is preferable to mark the beginning of the tragedy,” on the ninth.

The two temples are not the only tragedies associated with the 9th of Av. “A meritorious matter is brought about on an auspicious day, and a deleterious matter on an inauspicious day,” the Gemara says, and so bad things seem to be attracted to the 9th like a magnet. On the same date, the spies sent by Moses into Canaan returned with their discouraging prophecies—a sign of lack of faith that God punished by decreeing that the whole generation of the Exodus had to die before the Israelites could enter the Promised Land. More than a millennium later, the same date marked the fall of Beitar during the Bar Kochba rebellion, and the date when the Romans plowed the city of Jerusalem as a sign of its total destruction. The 17th of Tammuz also has several calamities associated with it. On that day, King Manasseh placed an idol in the Temple; centuries later, the Romans forbade the Jews to offer sacrifices there. The secret logic of history is revealed through this pattern of sin and retribution.

But the rabbis make what seems like a deliberate decision to end this tractate, which is devoted to calamity and repentance, with an episode of pure joy. According to the mishna, “There were no days as joyous for the Jewish people as the 15th of Av and as Yom Kippur, for on them the daughters of Jerusalem would go out in white clothes … and dance in the vineyards. And what would they say? ‘Young man, please lift up your eyes and see what you choose for yourself for a wife. Do not set your eyes toward beauty, but set your eyes toward a good family.’ ” There is something almost Shakespearean about this midsummer idyll, with its dancing maidens and wooing lads. It would be a mistake, the Talmud seems to say, to think of Jewish history solely through the lens of fasting; we must remember the feasting, too.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study,click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.