American Jews Speak English, but Our Sacred Texts Are in Hebrew

What happens when the most authoritative guardians of the tradition are sometimes baffled by the tradition themselves?

Literary criticAdam Kirschis readinga page of Talmuda day, along with Jews around the world.

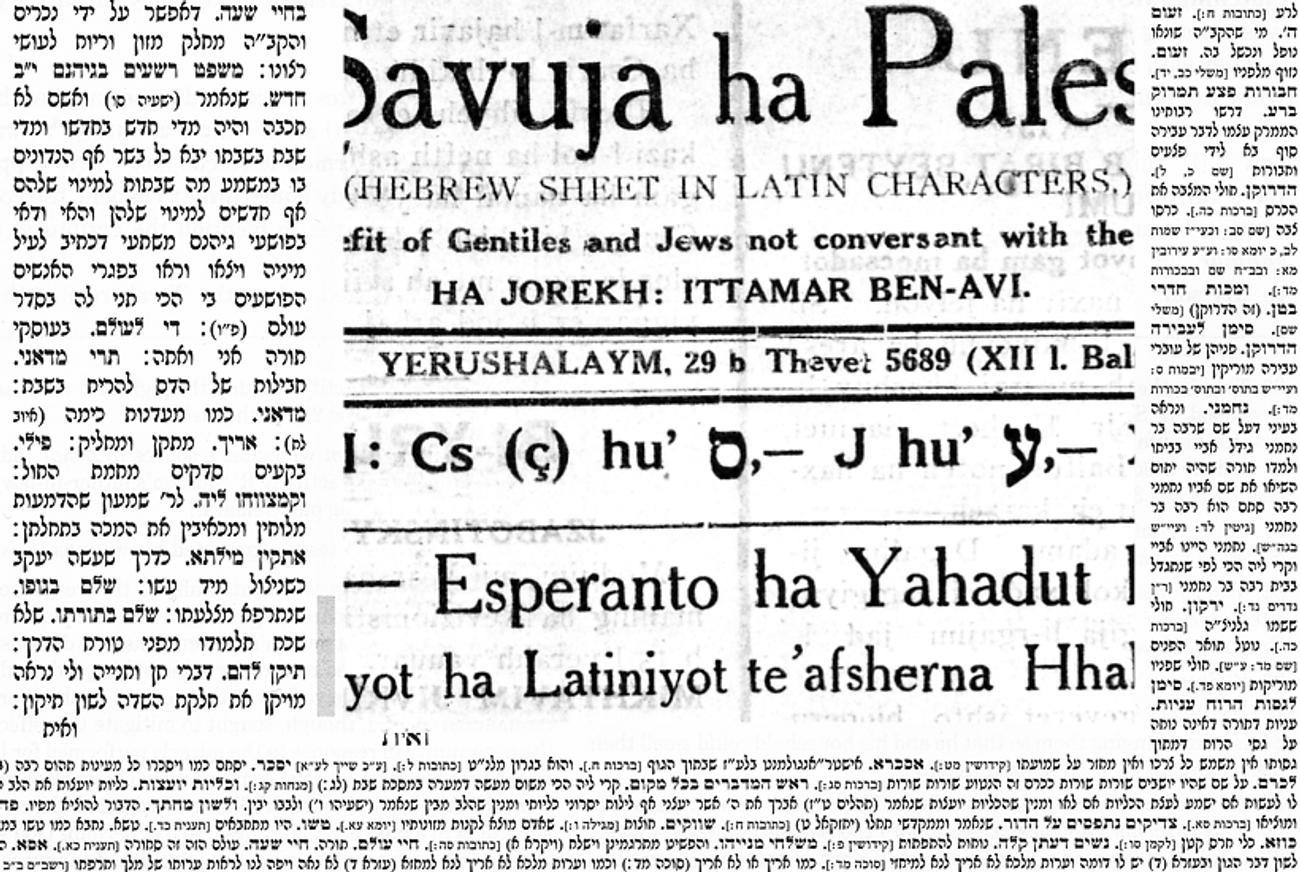

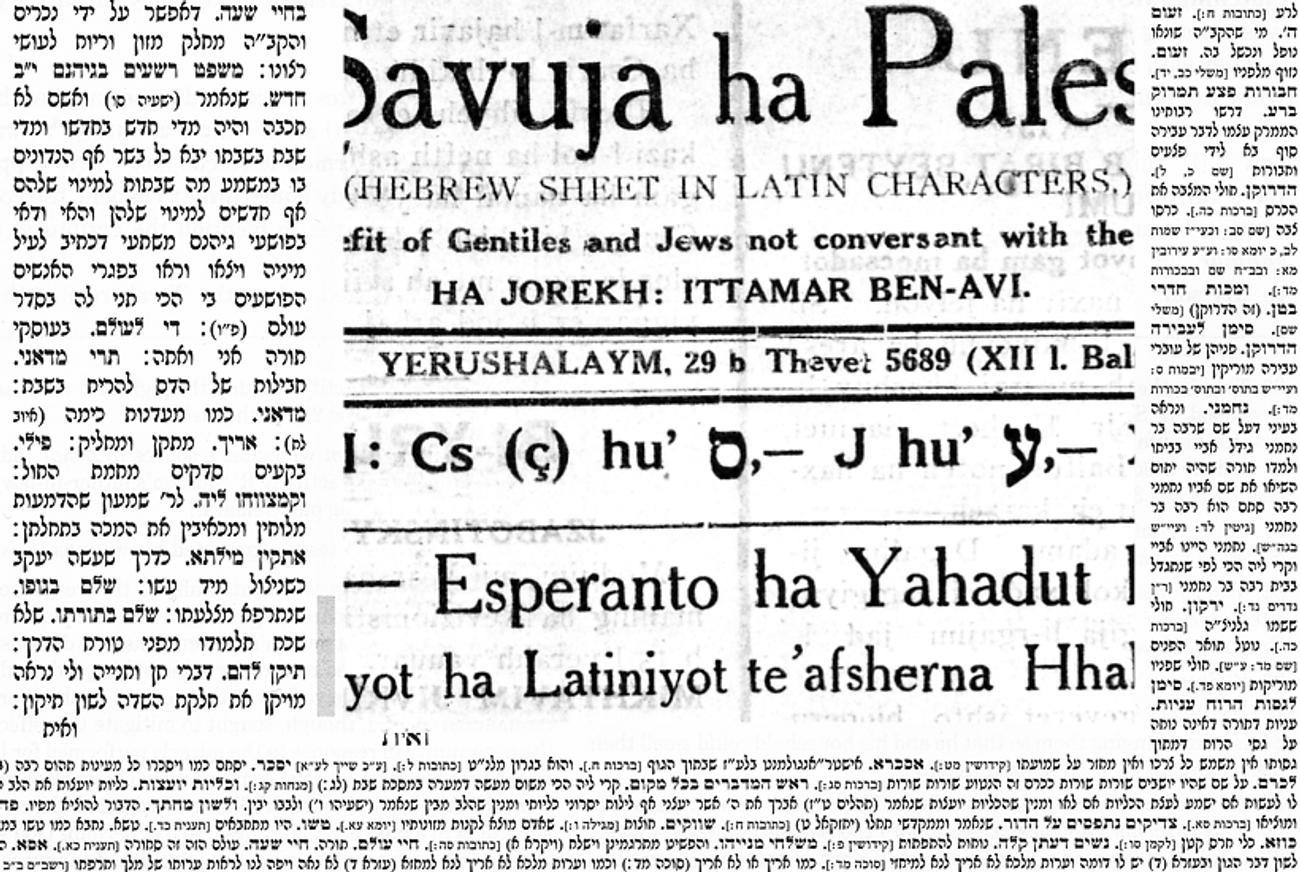

You don’t have to spend much time in a Reform or Conservative synagogue to realize that American Judaism has a language problem, one that’s simple to describe but hard to solve. American Jews speak English, but our sacred texts—the Torah readings, the prayers—are in Hebrew. As a result, most of us don’t know what we’re hearing, or even what we’re saying, during a prayer service. Yet if you try to reduce the amount of Hebrew in the service, by saying prayers in English, you lose the sense of connection with ancient tradition that is such a large part of Jewish spirituality. The only real solution to this dilemma would be for every Jew to become fluent in Hebrew, but we will be waiting a long time before that day comes.

It was consoling to read Daf Yomi this week, then, and realize that this is not just an American problem; it’s been with Judaism since the Babylonian exile. The language of the Tanakh is Hebrew, but by the time the Talmud was compiled, the Jewish people even in the Holy Land no longer spoke Hebrew as a native language; instead, they spoke the closely related Aramaic. And Jews in other parts of the classical world didn’t even know Aramaic, conducting their lives instead in Greek. Indeed, Philo of Alexandria, the biblical commentator who lived in the 1st century C.E., based his detailed explication of the Torah on the Greek translation known as the Septuagint; it’s not certain that he even knew Hebrew at all. Judaism has been a religion of and in translation almost since the beginning.

The language question emerges in the second chapter of Tractate Megilla, when the Talmud raises the question of how the Book of Esther should be read. It might seem obvious, but the Mishna begins by clarifying that the text must be read in the order it was written: “One who reads the Megilla out of order … has not fulfilled his obligation.” Further, like the Torah, it cannot be read from memory: A physical text must be there for the reader to look at. Later in the chapter, we learn that this should ideally be a dedicated scroll that contains just the book of Esther. If it is part of a larger book, say a scroll containing all the Writings, at least the pages of the Megilla must be noticeably shorter or taller than the other pages. This is to make visible to the audience that the reader is fulfilling the mitzvah of Purim by reading the Book of Esther, and not some other biblical text. Nor can you use just any ink in writing a Megilla: The Mishna lists several substances that are forbidden, including samma, orpiment, and komos, a type of tree resin.

The Mishna goes on to say that the mitzvah is fulfilled only if the Megilla is read out loud; reading it silently to yourself does not count. How do we know this, the Gemara wonders? After all, the scriptural basis of reading the Megilla is Esther 9:28, which says, “And that these days shall be remembered and observed throughout every generation, every family, every province, and every city; and that these days of Purim should not cease from among the Jews, nor their memorial perish from their seed.” Nothing is said explicitly about reading a book, just about “remembering.” But Rava finds an answer, by using the favorite exegetical tool of verbal analogy with another biblical verse. Just as Esther commands us to “remember,” so in Exodus we find God telling Moses, “Write this for a memorial in the book”; “Just as there [it says] in a book, so too here, in a book,” Rava explains in Megilla 18a.

Even so, the Gemara points out, this analogy only proves that we must read the Esther story in a book. It doesn’t prove that the book must be read aloud, as the Mishna tells us: “Perhaps it requires merely looking into the book.” How do we derive this further rule? Again the rabbis have a scriptural explanation, based on yet another instance of the word “remember.” “Remember what Amalek did to you,” reads Deuteronomy 25:17, and then two verses later, “You shall not forget.” One of the key principles of Talmudic exegesis is that the Torah does not use redundancy for no reason: If the Torah says “remember” and then “do not forget,” it is because we are meant to learn two different points of law. So, the Gemara explains, “do not forget” refers to “the heart,” while “remember” refers to “the mouth”: We must not just remember silently, but out loud.

It is at this point that the language question raises its head. We know that the Megilla must be read out loud from a book, but does that book have to be written in Hebrew, or is a translation also valid? The Mishna’s answer at first seems to be contradictory: “If he read it in translation or in any other language … he has not fulfilled his obligation. However, for those who speak a foreign language, one may read the Megilla in that foreign language. And one who speaks a foreign language who heard the Megilla read in Ashurit [that is, Hebrew], has fulfilled his obligation.”

A whole series of questions immediately presents itself. First the Mishna says that reading the Megilla in translation is invalid; then it says that it’s permitted to translate the Megilla into the language an audience understands; then it says that Hebrew is always valid even if the audience doesn’t understand it. (Actually, what it says is that Ashurit—the “Assyrian” script in which Hebrew is written—is valid; but does this refer to the language or merely the script, so that a foreign language written in Ashurit is also OK? According to the Koren Talmud, later commentators disagree on this point.) Which is the correct procedure?

The Gemara boldly attempts to unravel the Mishna’s answer. Perhaps the reason why reading in translation is forbidden is that it violates the rule about reading the Megilla aloud directly from a text. In other words, perhaps what the Mishna means to forbid is looking at a Hebrew text of the Megilla and translating it out loud into Aramaic for an Aramaic-speaking audience. After all, this would essentially be a form of reading from memory, since it requires the reader to come up with a translation in his head. But no, the Gemara decides, this is not what the Mishna means. Even if you were reading an Aramaic text aloud, it would still not qualify.

But how are we to reconcile this rule with the Mishna’s next statement that “for those who speak a foreign language, one may read the Megilla in that language”? The answer, according to Rav and Shmuel, is that the Mishna doesn’t mean just any foreign language, but specifically Greek. Here we see that Greek enjoyed a special status as a language of Judaism, even though it was not actually a Jewish language (not unlike English today, perhaps). Indeed, a little later on, Rabban Shimon ben Gamliel rules that books of the Bible can be written in only two languages, Hebrew and Greek. This fits with the legend that the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, known as the Septuagint, was guided by God. When King Ptolemy of Egypt ordered 72 Jewish sages to translate the Bible into Greek, each one came up with exactly the same text, an obvious miracle. The story helps to lend authority to the Greek Bible in a way that would have been appreciated by the many Jews, like Philo, who knew no other language.

Still, Rav and Shmuel’s elegant solution doesn’t go uncontested. Unfortunately, there is a baraita that says, “If one reads the Megilla in Coptic … Elamite, Median, or Greek, he has not fulfilled his obligation.” This seems pretty explicitly to contradict what Rav and Shmuel said about reading the text in Greek. Matters get more complicated still when the Gemara mentions another baraita that directly refutes the first one: “If one reads the Megilla in Coptic to Copts … in Elamite to Elamites, or in Greek to Greeks, he has fulfilled his obligation.” The principle at work here, the Gemara decides, is that it is acceptable to read the Megilla in any language so long as the audience understands that language.

By that logic, it seems that it would be halachically acceptable to read the Megilla in English to an American congregation, though I don’t know what the actual law is on this point. Still, the Talmud preserves a special place for Hebrew: Hearing the Megilla in Hebrew always fulfills a Jew’s Purim obligation, even if he doesn’t understand what he’s hearing. This may seem to contradict the Gemara’s earlier logic, but it is not so. Rather, “it is just as it is with women and uneducated people [ami ha’aretz]”; these categories of people usually don’t know Hebrew, yet they are still able to discharge their obligation by hearing the Megilla in the holy language.

And then Ravina intervenes with a remarkable statement. Even the sages, he points out, do not always fully understand the Hebrew they are reading; even they encounter words whose exact meaning has been lost with time. The most authoritative guardians of the tradition are sometimes baffled by the tradition. Indeed, they sometimes have to turn to “women and uneducated people” for guidance, as we learn in a series of anecdotes. The sages, we read, “did not know what is meant by the word seirugin,” until one day the maidservant in Yehuda HaNasi’s house “said to the sages who were entering the house intermittently rather than in a single group: How long are you going to enter seirugin seirugin?” This showed them that the word meant intermittently, which in turn clarified one of the rules of Purim, that the Megilla may be read seirugin, at intervals, rather than all in one go. It’s pleasing to think that, on occasion, even the greatest teachers of Torah could be taught something by the common Jew.

***

To read Tablet’s complete archive of Daf Yomi Talmud study,click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.