Fading

The one custom for celebrating Shavuot is to stay up all night and study Jewish texts. But will we continue celebrating the printed word as more and more of what we read is electronic?

Most Jewish holidays have a ritual or physical symbol connected with them, a means of accessing the import the day. In the spring we rid ourselves of leavened products; in the fall, we build temporary structures; in the winter we light special candelabras. The holiday of Shavuot is an anomaly. There are no rituals that need to be performed, no special blessings to be pronounced. This is a holiday of pared-down simplicity, symbolized by the custom in Eastern Europe of making paper-cuts (called “shavuoslekh” in Yiddish) to decorate the home and synagogue.

The one custom for Shavuot is to stay up all night studying Jewish texts. This custom itself was enabled because of a particular innovation in food technology, as historian Elliot Horowitz has explained: the availability of caffeine. Horowitz discusses how once the stimulant became widely available in the 16th century, it enabled even the most sluggish among Jewish scholars to remain in a roused state through the early morning hours of Shavuot. Somehow this tension, between the corporeal (of our need for stimulants, or at least rest) and the spiritual aspects of awaiting revelation feels particularly Jewish to me, given the way our religion is rooted in the body.

The study of text on Shavuot takes no fixed form. Compilations of texts for this nocturnal holiday do exist, and they contain excerpts from the Torah, Mishnah, Talmud, and kabbalistic texts, but these are suggested modes of study. You could read anything really—Art Spiegelman’s Maus or stories by Amir Gutfreund. Shavuot is a time for Jews to focus on what it means to have a text and grapple with it, to be and to celebrate being the people of the book.

But what does it mean to be the people of the book these days? Recently, I went with my 10-year-old daughter to our local Borders, which was having a going-out-of business sale. My daughter looked at me and said, “I don’t think there will be any bookstores when I’m grown up.” This is a child who is notoriously pessimistic; she often fears that she will miss the school bus or doubts that she’ll able to finish her homework. I am usually quick to reassure her. In this case, I couldn’t. I think she’s right.

I appreciate so much about our electronic world, but I worry too, particularly the way it might be changing our approach to reading. Sven Birkerts writes of reading as an “ignition to inwardness, which has no larger end, which is the end itself.” In Ethics of the Fathers, Rabbi Ben Bag-bag (whose own name is probably a play on Torah with its repetitive use of the second and third letters of the Hebrew alphabet) writes, “Turn it over and turn it over for all is in it.” How do we do that, how do we manage that sustained attention, let alone valuing one book, our Hebrew Bible, above all others, in our times?

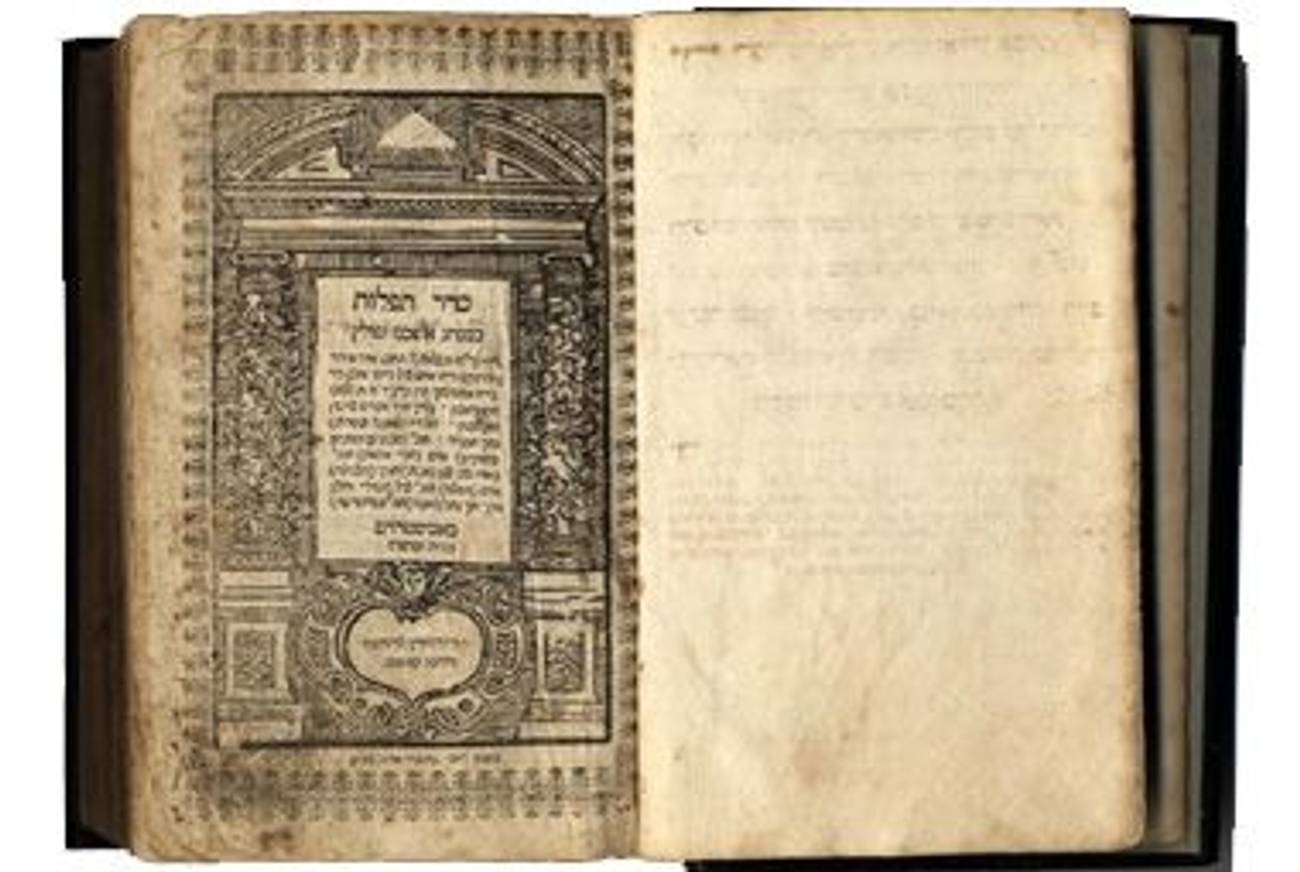

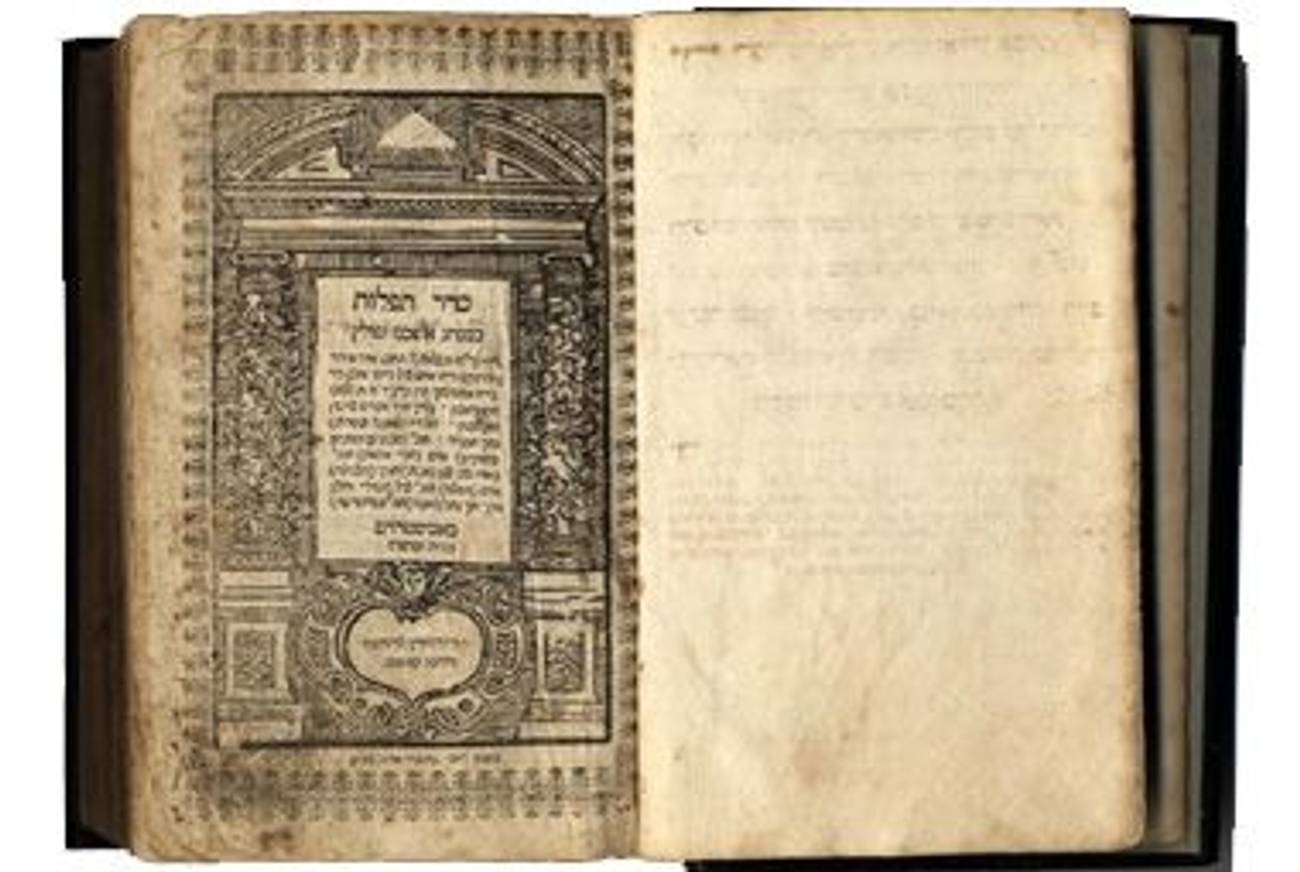

Another historian of the book, Anthony Grafton has written of his Kindle that it “liberates” him because he always has a text to read on a long flight. Yet he also expresses his concern that postmodern reading is “rapid, superficial, appropriative and individualistic.” Physical objects give us information that we can’t glean electronically. Grafton writes of a scholar in an archive noting the smell of vinegar on a text which makes him aware that it had been disinfected during a cholera epidemic, giving us clues about the spread of disease.

I believe that Jewish books as objects will endure even if we move, as we seem to be doing, to a culture in which our texts are wholly electronic. We have been a culture that places a value on hiddur mitzvah, on the aesthetic value behind doing any commandment, so I believe Jews will continue to find value in lovely books for ritual use. Most of Jewish literature—from the Bible through rabbinic literature and modern halachic responsa—is available in electronic form. Yet we still handwrite scrolls and create beautiful book objects. It’s difficult to imagine the Torah ever being read from a Kindle for a congregation; we need rituals around our readings. So, we will have to stay in the corporeal and spiritual once again, using modern book technology as it is valuable, while taking time to sniff the ink on our handwritten Torah scrolls.

The revelation of Shavuot in the Bible, the Ten Commandments, begin with the letter aleph, of the word anokhi. Aleph is a silent sound, so all language that emanates from this revelation begins in silence. The text of the revelation is itself smashed and re-written. Moses creates one set of tablets, which he destroys; then he is told to recreate them; and then the destroyed tablets are still placed in the Ark of the Tabernacle, rendering it in effect the first geniza, a repository for a Jewish text. I think it’s essential that both old and new versions were placed in the ark. Perhaps this most ancient of biblical models can serve as a guideline for the ways we produce and consume texts today, that we can find a way to make an ancient desire to immerse oneself in a text to enlarge and deepen our experience, along with the liberation we find in the information instantly available at our electronically charged fingertips.

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.