Can German Jews Pray for Their Country?

In Germany, synagogues ask whether they can say the traditional Prayer for the Country

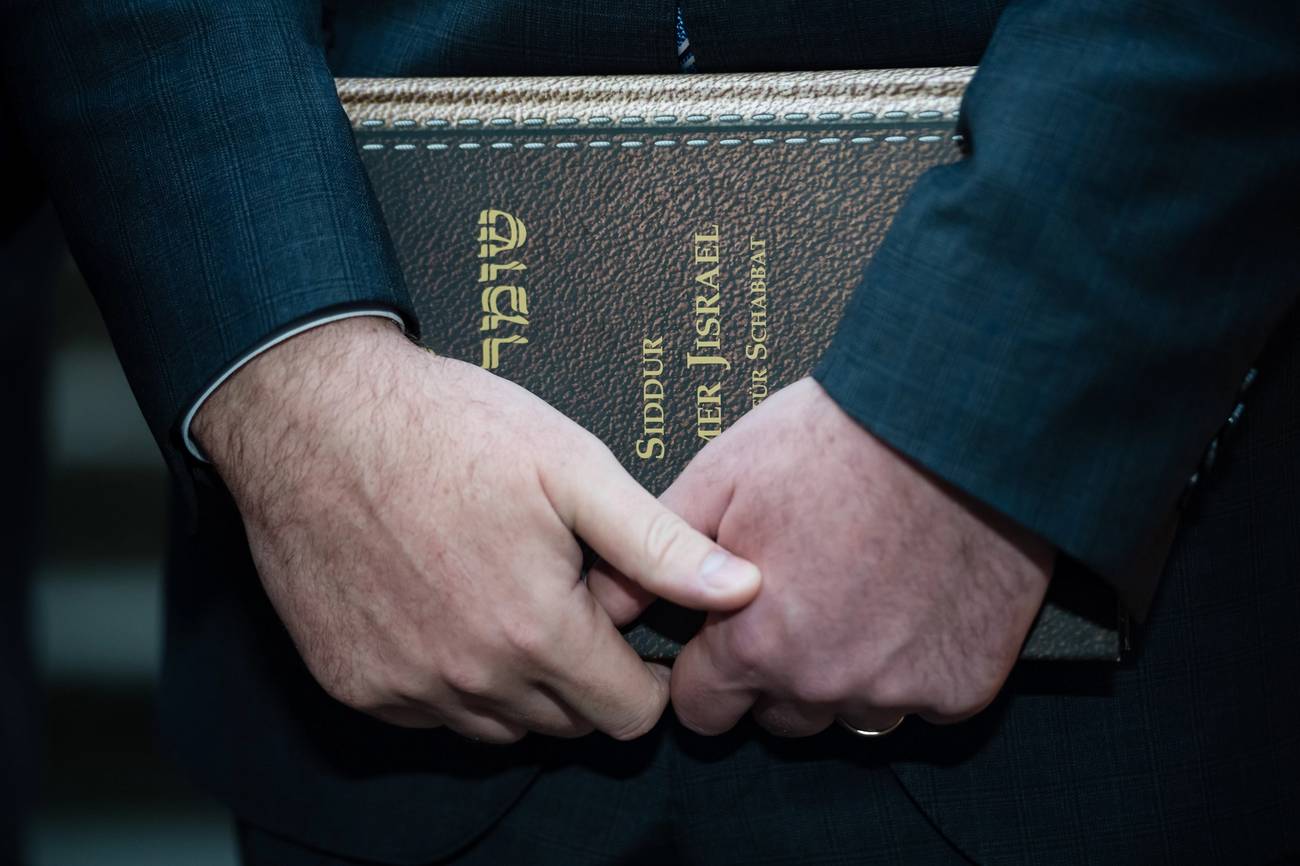

After Kiddush one day in February, a crowd smaller than a minyan lingered at the Oranienburger Strasse Synagogue in Berlin. Having already prayed and bentshed after Kiddush, they remained for a shiur, a talk, on the history of praying for the government. When the shiur’s subject was announced, the congregants shifted in their seats. Rabbi Nils Ederberg got up and spoke of a special siddur found in the Jewish Theological Seminary’s archive in the United States. This siddur made its way from 1930s Germany to the United States, like countless other possessions brought over by Jewish refugees. What makes it special? A handwritten addition to the Prayer for the Country—the country being Germany—naming the country’s leader, Adolf Hitler.

Today, the Prayer for the Country, a regular feature of Jewish worship in most countries, is a taboo subject for many here. Though within easy walking distance to the Reichstag, the congregation, like many in Germany, prays for the State of Israel but never for Germany, their country of residence. German congregations once prayed for their country, and now, understandably, seldom if ever do. Which raises some questions: How did this tradition of praying for the Jews’ diasporic countries got started? And where it stops—in Germany, for very good reason—is it ever time to bring it back?

There are various reasons why Jewish communities began to pray for the well-being of the government. The Jews exiled to Babylon after the destruction of the First Temple were instructed to “seek the welfare of the city to which I have exiled you and pray to God on its behalf; for in its prosperity you shall prosper” (Jeremiah 29:7). In the millennia since, this verse and various talmudic passages (such as Pirkei Avot 3:2) led to the custom of Jewish communities praying for the well-being of their country of residence. Hanoten Teshua, the classic prayer originating from this practice—you can read one version here—has been said since the 16th century in synagogues around the world, from Amsterdam to New York to Berlin.

German Jews became emancipated in 1871 under Emperor Wilhelm I. During the reign of his grandson Wilhelm II, the New Synagogue of Berlin, a leading Reform congregation, included a prayer for the emperor in its prayer book Seder Tefilot le-kol ha-Shanah (1898). The prayer was a departure from Hanoten Teshua. Written in German, it asked for a blessing for the king, Wilhelm II, so that “truth and justice would blossom under his scepter.” As it continued, concern broadened from the emperor and empress to the German state, calling on God to “bless the entire German Vaterland [fatherland]” as well as “our Vaterstadt [father city], granting it success and prosperity.”

The New Synagogue’s prayer retained themes of the earlier Hanoten Teshua prayer. Both featured calls to bless the country’s leader, for the leader to act favorably toward Israel, and for a form of redemption. Yet the New Synagogue’s wording featured something new: identification with the German Empire. This prayer claimed a dual Jewish German identity, spoken by congregants who were not only residents of the Vaterstadt Berlin but citizens of the Vaterland. It’s hard to imagine saying a similar prayer today.

“How can you identify with Germany in that way?” asked Daniel Stein Kokin, when he first decided to look into the prayer for Germany. His question began in 2016 when Stein Kotkin, now 44, was living in Berlin, teaching at the University of Greifswald, and he noticed the absence of the prayer while attending services. His interest led to a Berlin Limmud presentation and a shiur at the Fraenkelufer Synagogue. At the core of his work was a question that continues to be asked in 2020: “How do German Jews identify themselves?”

In 1893, that question led to the founding of the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith, or Zentralverein. Founded to help ensure the rights granted to Jewish citizens and combat anti-Semitism, community leaders were aware that emancipation granted equality only in the eyes of the law. Jewish Germans needed to understand that they were no longer wandering Jews and commit to their status as German citizens.

In 1945, that question seemed to be a relic of another era. The previous 12 years had turned German and Jew into opposites. The German Rabbi Leo Baeck declared, shortly after surviving Theresienstadt, “for us Jews from Germany a historical epoch has ended ... Our belief was, that the German spirit and the Jewish spirit could meet on German soil and through this marriage could become a blessing. This was an illusion. The era of Jews in Germany is over once and for all.”

A prayer for the country that murdered millions of Jews seemed more blasphemous than praying for the empire that destroyed the First Temple. Yet perhaps time blunts blasphemy. Tefillot le-khol ha-Shanah, a prayer book published by the official Berlin Jewish community in 1968, included two variations of the prayer for the state. Though both versions ask for God “to bless the Vaterland [fatherland],” only version B describes the Vaterland as “deutsches [German].”

The inclusion (or absence) of a direct reference to Germany is one way a community asserts their understanding of Jewish German belonging. Though the Berlin Jewish community is by far the largest in Germany, there are numerous smaller, active communities scattered throughout the country. (These are “communities” in the informal sense—not to be confused with the “official” Jewish community as recognized and defined by the government: the Central Council, or Zentralrat.) Some of these congregations, including those in the towns of Oldenburg and Braunschweig, have featured two variations of a prayer to Germany in recent years that respectively reference the Bundesrepublik, the Federal Republic, and the Bundesrepublik Deutschland.

In the German capital, progressive synagogue Bet Haskala prays from Seder ha-Tefillot (2010). The siddur includes prayers for the “Regierung [government]” and for “Internationale Verständigung [international understanding].” Neither prayer mentions the Vaterland or Bundesrepublik.

In Potsdam, just outside of Berlin, a prayer for Germany has been said at various official events held at the Reform-affiliated Abraham Geiger College, such as the rabbinic ordination ceremonies. The German government has been involved in supporting the school and its Conservative counterpart, Zacharias Frankel, as well as the resurgence of Jewish studies throughout the country. It’s a stark reminder that though contemporary Germany stands in the shadows of the Third Reich, today’s country has moved on (even as many Jewish residents feel that their safety and security have not always been taken seriously in recent years).

Abraham Geiger rabbinical student Max Feldhake’s interest in the prayer for Germany stemmed from his belief that Jewish diasporic communities “need to have adequate responses to issues surrounding the state and nation.” He doesn’t question if a prayer for Germany can be said. According to Jewish law, it can be. In postwar Germany, the prayer is one of identity, rather than law.

Feldhake believes that German Jews should try to write a new prayer and wonders how the unique German Jewish experience might translate. “A prayer for the state is an expression of feelings held by the community,” he said. “And if you don’t have consensus about how you feel, it’s quite difficult to create a liturgical motif for that.”

A poignant and sensitive prayer that addresses the German context remains missing from the liturgical toolbox. If written, some German rabbis, and their communities—again, informally speaking, as the official Central Council has no say over liturgy—could use it to strengthen their identity as Jews who care about the well-being of their country of residence.

Of course, the physical and emotional legacy of the Shoah further complicates any attempt for a community consensus. Each generation has lived in a different Germany. What is Germany today was occupied by the Allied Powers, then divided into East and West Germany, and then, in 1990, reunited. Each government had its own way of addressing the Nazi past and understanding its relationship to it. Jewish communities in Germany sought to find various ways forward as Jews, but not necessarily as Germans.

In the words of Leo Baeck, the German spirit and the Jewish spirit have begun to meet again. In the past 30 years, many migrants and refugees have made their way to Germany, including a large influx of Jews from the former Soviet Union. A smaller number of Israelis and Jewish Americans flocked to Germany, many with a German passport in hand, a right they have as descendants of those who had their German citizenship stripped in the 1930s.

As Jews have chosen to live, or remain, in Germany, many have become residents, if not always citizens, at a time when Germany simultaneously navigates both an uptick in far-right activities (as the Yom Kippur attack in Halle, Germany, last fall illustrated) and a diversifying society (1 in 4 German residents has an immigration background) that challenges an ethnocentric German identity.

In that paradoxical country, Berlin is a relatively tolerant, cosmopolitan place, and an easier place for Jews to call home—but a new prayer for the city, the Vaterstadt, would ignore the rest of the German Jewish community. And although Jewish life might be easier in Berlin, its Jewish communities are not isolated from events impacting Jews that occur elsewhere in the country. In February, when the centrist CDU (Christian Democratic Union) formed a coalition with the right-wing AfD (Alternative for Germany) in elections in the state of Thüringen, the morning minyan at Abraham Geiger College reacted. The events gave them “Anlass” [cause] to add a prayer for the German government. One that, they hope, can allow truth and justice to prosper for all of its residents.

Paige Harouse is completing a service year in Holocaust education in Berlin. She’s a student and author interested in religion, identity, and nationalism.