Guess Who’s Coming to Seder

A Passover in Berlin stirs up questions of freedom and faith

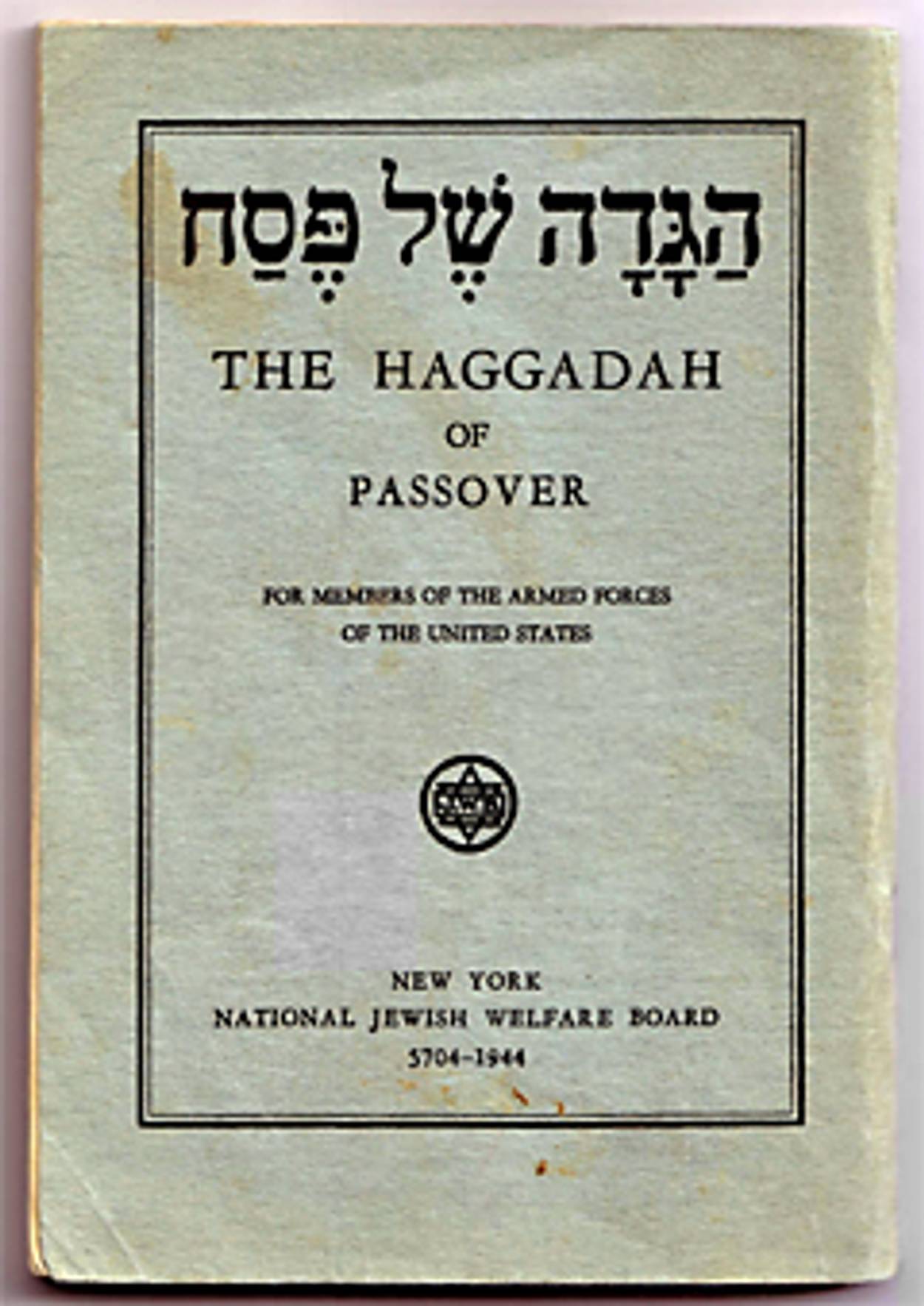

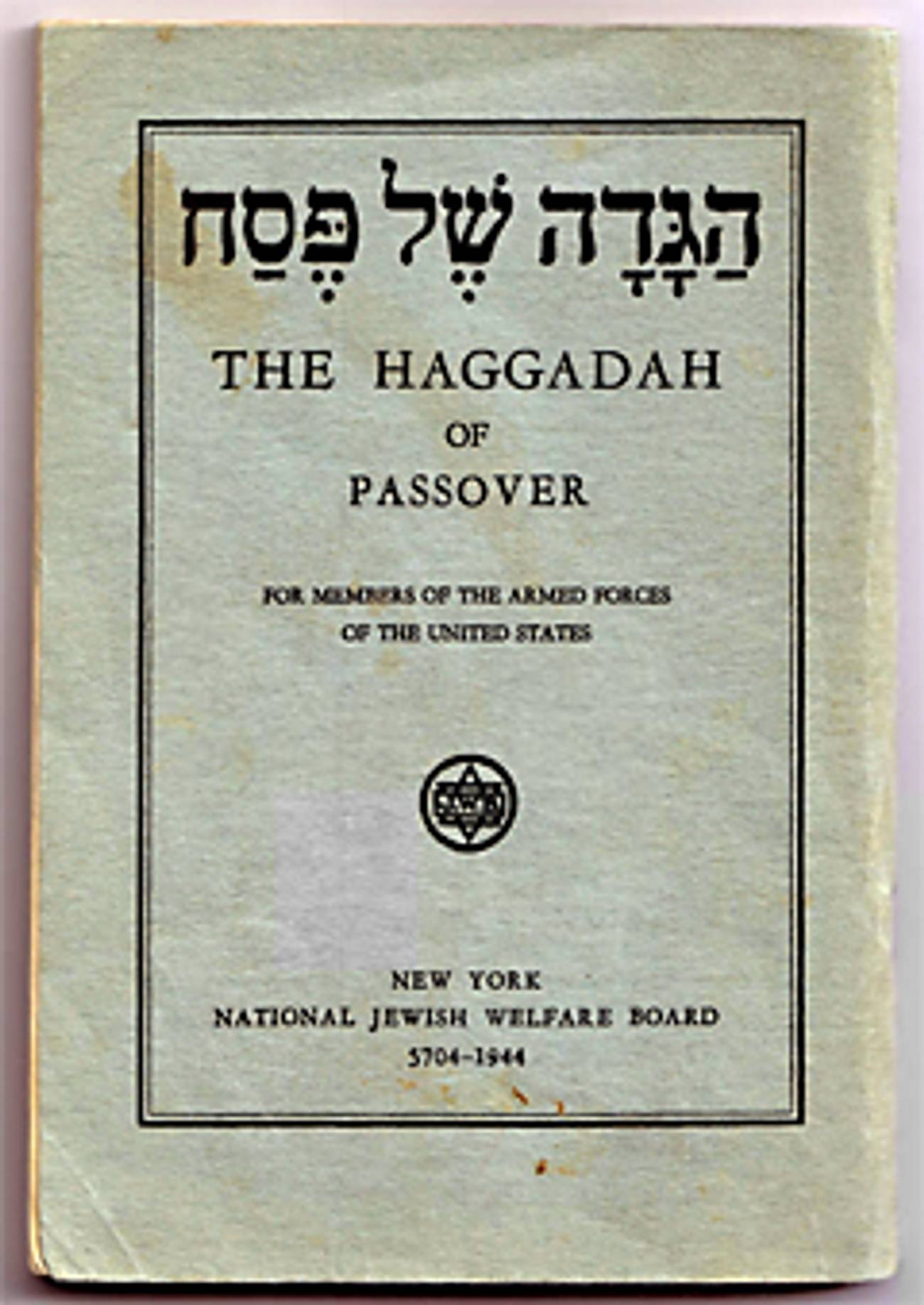

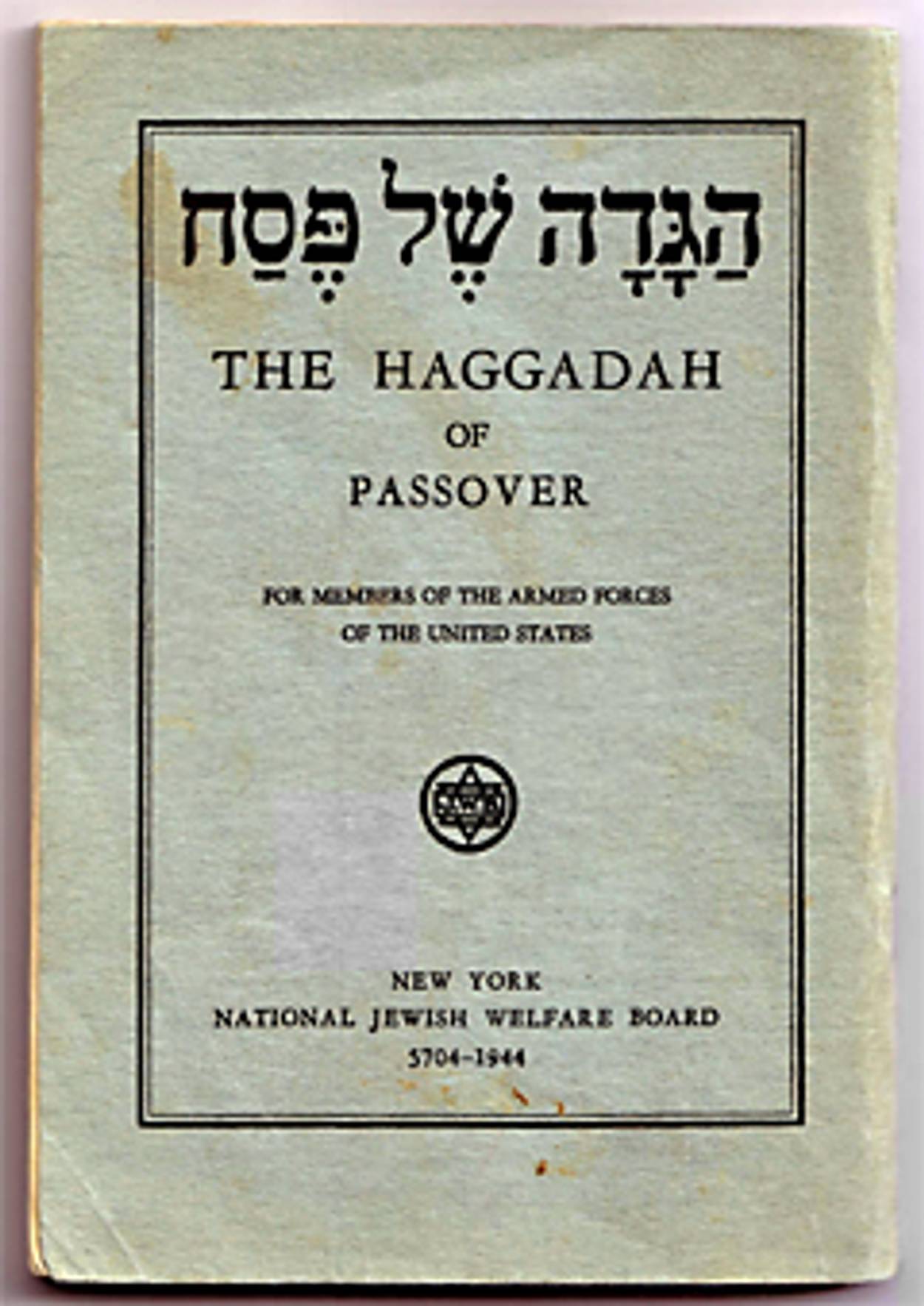

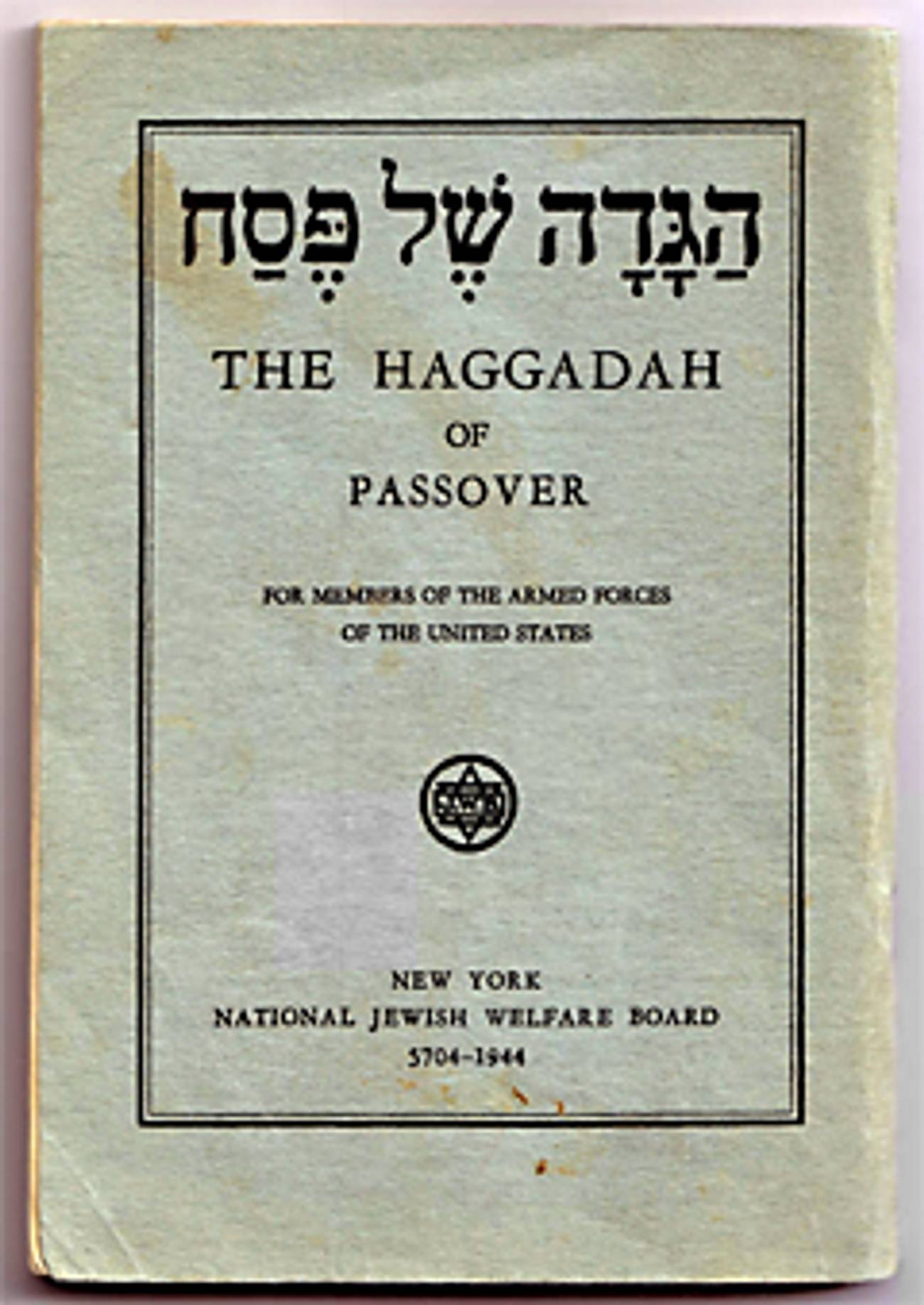

I pulled out our single haggadah yesterday to admire it, shamelessly, on the kitchen table. It’s a pamphlet, basically: an iron-gray paper cover, scruffy and soft like construction paper, stapled on the right-hand side. Two dark splotches look like coffee but may well be faded wine. The pages curl pleasantly from the repeated touch of wet fingers. The typefaces—an old-timey, newspaper serif for the English, a florid Hebrew script—show up remarkably clear and true on the page, like that magical moment in the optometrist’s office when the right lens swings into focus. Turn to the back page and you’ll find the lyrics to The Star-Spangled Banner and America, right across from the Hatikvah: all kinds of freedom songs, rubbing up against one another.

Our haggadah dates from 1945, when it was printed “for the members of the Armed Forces of the United States,” as its cover proclaims, sponsored by something called the New York National Jewish Welfare Board. According to the flyleaf, it’s one of 260,000 copies, printed (with increasing urgency) between 1943 and 1945. When our haggadah was crisp and new, Germany was falling, and Allies were liberating concentration camps, peopled with the dead and nearly dead. Bringing “freedom” to such places is almost bitterly laughable: even if your body survives, who would ever feel free of such memories?

We bought this haggadah during the year we lived in East Berlin, to celebrate our very first seder among Germans and Americans. An odd mission for me, a German-American ex-Catholic and for my husband Seth, an American Jew of remarkable laxness, both of us atheists. Our Jewish credentials are an unorthodox American mix: ten years living in New York, some Hebrew school, a growing if miscellaneous bookshelf of Jewish-American writers. And our plan in holding a seder in Germany, I realize now, was just as all-American: artlessly simple to start, mind-bogglingly ambitious to complete.

We wanted to start our own Jewish tradition: to teach our German friends something about Judaism that does not revolve around grainy documentary footage and the inescapable guilt of their grandparents. And most audaciously, to bring a little levity to this experiment: fewer bombs, more humor, even if it’s clouded by the gallows. Modern Germans rub up against Jewish culture constantly as a culture of crisis, of national shame and of pervasive memorial. What really jarred me was how little contact they seemed to have with actual Jews. What about ongoing Jewish life, beyond its attempted annihilation in the past?

* * *

We moved to Germany to pursue two year-long grants: Seth’s in musicology, mine in journalism. It was a year that began with an all-expenses-paid summer of language school and hotel living by the Rhine. What could be finer?

Little rumblings began immediately. Strolling along the Rhine under bright leaves, we’d meet, say, an older couple, he with his Alpine walking-sticks, she with her blue, hand-embroidered sweater. We chat with casual civility and grace, in another language, too. But then the long shadow drops, the shifty mental calculations start up: how old were they back then? How complicit, by extension? The very ground you’re standing on emits a few sinister spores. Heuchelei! Hypocrisy! How could people like that have done this? The more we came to love Germany—its liberal, secular Enlightenment values; its emphasis on education and the arts; its wealth counterbalanced by environmentalism and social welfare; its careful foreign policy; every sanity, in short, our own country seemed to be careening away from—the more this contradiction clung. It undercut many of our best moments in Germany, a rift you never really resolve. You just learn to live with it, the way you live with the awareness that you’ll die.

Soon I noticed other things—chiefly, the continuing cultural costs of the war. I knew about the scientists, poets, lawyers, philosophers who fled and never returned, who taught their children and grandchildren, never to return. But what I missed in Germany was simpler, more localized: no Jews means no Jewish culture. Well, I exaggerate: there are Jews now in Germany, most notably a community of expatriate Russians in Berlin. While their symbolic importance is high, their actual numbers are low—and, from where we sat at least, their impact on dominant German culture felt slight. Just like my African-American friend Talaya, consternating German hairdressers with her kinky hair, it was one of those small, unanticipated lacunae of moving overseas that mushroomed overnight into a real problem, a vehicle for my homesickness.

In a land of heavenly bakeries, bagels come frozen and hamantashen are non-existent. Same with corned beef, lox, latkes, matzoh-ball soup, all those good winter eats. In this cradle of Western music, klezmer fills the concert halls, but no one knows it’s dancing music, no one sings along. Many have read their Wiesel and Arendt, but they laugh nervously at Philip Roth; they don’t know I.B. Singer, Grace Paley, A.B. Yehoshua at all. Rules are rules, a thousand percent non-negotiable. Nobody blurts out the wrong thing and belly-laughs; no one nags. Hardly anybody talks with their hands. Stereotypes, sure, but only in Germany did I see the kernel of truth in them. Who knows how much of this is New York or Jewish or both? I missed all of it, sorely.

So I went on the benevolent counterattack. In language class I unloaded an arsenal of Yiddish words, many still alive in German: meshugenah, mishigas, schlep, schnorr, all those sloppy, hilarious words so appropriate to the welcome-to-the-sausage-factory scenario of adults learning grammar again. Together with the other students—a Texan and a Russian—we learned that Mensch here just means “person,” not a man you harangue your daughter to marry. Naschen in Germany refers exclusively to sweets. One day I bumped into the Russian hard and exclaimed, “Entschuldigung! Ich bin solche Schlimazel!” (“I’m sorry! I’m such a schlimazel!”) Blank faces all around the table.

* * *

September rolled around, and we moved from Bonn, where we’d gone to language school, to Berlin, where our year-long grant projects would play out. My sense of otherworldliness faded, but still I sniffed the air for opportunities to explain ourselves, to enjoy Berlin our way.

Not that it takes much effort. Bonn is a drowsy fairy-tale town on the Rhine, a hugely enjoyable place to shelve your real life and learn a new language, but Berlin is wonderful precisely because it is real—sprawling and electric. Casually anarchic, crammed with experimental art, it has its own bone-dry wit, Berliner Schnauze, which feels uncannily like home. Our street came to feel like a sunnier Brecht-Weill stageset. Enter our landlord Thomas, for example: bowtie flapping and spats a-sparkle, in round black glasses and hair slicked back with water. One morning he invited us, impromptu, to brunch. “Hallo, Jood and Zet! Come meet Reza and Avi! We have just stolen the corner building back for them from the Nazis!” That’s how we learned Thomas the lawyer also defends claims from once-German Jews, restoring family property. Our German teacher Dirk shone with calm and intelligence, a lovely, soft-faced man from the former GDR. He questioned us guilelessly about what Jews eat and do, what certain holidays mean. I called him our “Jewish mother” when he pressed Seth about homework. Snarky and curious, our German drinking buddies—Chrish, Thomas, Heidi, and Bianca—even asked me Jewish questions: tall, striding, blondly Teutonic me, who fooled all comers here: hardly the go-to girl for things Jewish back home. Their questions are shy, nothing big: asking us to explain Yiddish words we drop, comparing kosher rules to Turkish halal. Clearly, we’re the one-eyed men here, now half-kings.

The year turned; it was almost spring. I had been nursing the idea of our first seder for weeks now. My mother- and brother-in-law planned a visit, and their arrival fell on the first night of Pesach. Seth and I wheeled into action and invited a good 20 people, not one of them Jewish. My mother-in-law Barbara was ecstatic; she wrapped matzoh in laundry and smuggled it in her suitcase. (We haggled but decided against gefilte fish: too leaky.)

I love seder. All his life Seth had been only fitfully observant, but when we moved to New York, we always scored a seder invite from someone—and always attended, our one persistent link to the faith. What’s not to like about a holiday tailor-made for strangers and children, loaded with audience participation, fueled by wine and song, explaining freedom in all its joy, terror, and responsibility? Having sat at the kids-and-Gentiles table at plenty of seders myself, I like seeing how the ceremony shape-shifts from house to house, elegantly ad hoc and durable, always recognizable. For weeks I’ve been fit-to-bust to share this experience with our friends.

But when the day arrived, exactly around charoset-apple-chopping time, I started to panic. For one, cooking for 20 with a dorm-sized refrigerator was no joke. We had no haggadahs, and Seth insisted on searching bookshops, today, for them. The panic deepened: Why were we doing this? Was it wrong to cherry-pick your holidays? Atheists that we are, is it lying? Was I a faker, an ex-Catholic who thought she’s going to explain Judaism and repair one inch of the Holocaust’s many breaches? All my fine ideas and proudly strung-together facts of Seder suddenly seem like used confetti: grubby, dust-tinged, an insult to any real celebration.

Then Seth burst in with lamb, horseradish, parsley, a henhouse worth of eggs—and a real haggadah! Not so much the product of calculated odds as enormous luck: he had strolled into the first used bookshop he saw and asked bald-facedly: “Haben Sie einige Haggadah für Pesach?” Do you have any haggadah for Pesach? The bookseller snorted—meaning, bloody unlikely, son—then limped over to the right shelf, and clocked a real double-take at his find: our Army-issued, English-language haggadah, uncannily materialized for the occasion. Back at home, though, we had only a minute to marvel at it, because the guests were already arriving. Everyone came loaded with wine; Chrish had whipped up an eggy, cream-cheese custard, crisply brown; a more un-kosher complement to our beef stew you can hardly imagine. Everyone sat, a little shyly, and we started.

And the flubbing started soon after. The Germans were having trouble following the baroque English during Kiddush, so we quickly veered off into our own English and German. We skimmed nervously through the haggadah for the parts we know: the Four Questions, the four types of sons. We were reciting the plagues—blood, frogs, gnats, fly-swarms, cattle plagues—just as a plate of matzoh caught on fire. Thomas, one of the Germans, slapped his napkin desperately at the evil votive candle, looking deeply rattled: Their sacred bread is on fire! We sped on to Dayenu to soothe him: it’s enough, it’s enough. Then another little fire started, from another pesky candle; Barbara doused it deftly with wine. We blessed pesach, matzoh and maror, juicy Prussian horseradish, a fiery drop of which was enough to sprout hair on your tongue. And god bless those Germans: they obediently choked down the entire dollop, smiling tearily about how “nice” it was.

And then it was almost over. Already Seth’s brother Chance was clattering around, trying to find the afikomen. Was that it? We should have planned better; we shouldn’t have screwed up so roundly; what was I thinking, killing our guests with bioweapons-grade maror and an unholy zeal for votive candles? My eyes pinged nervously to the uneaten eggs on our plates—how did we miss that part?—and I announced robotically, a desperate nonsequitur to close the ceremony: “Heute feiern wir Freiheit. Wir sind frei, miteinander zu feiern.” (“We’re celebrating freedom today; we’re free to celebrate with each other.”)

And that was it, isn’t it? The right lens clicked into place; the room, its air particles and faces like pale balloons, everything seemed sharper. We were teaching others about freedom and Judaism, but we were also learning. We’re free to bungle this, but also to recover from mistakes. And it’s no small thing that we felt free to do this in Germany, and that Germans stepped into our circle—with a shame deeper than our mere embarrassment—and tried to learn with us. We showed our friends something of Judaism they’d never witnessed: a ceremony that was still rare in these parts, but also certain contradictory truths about freedom: that it must be earned, that it was laced with suffering and doubt, that it was wildly precious and fragile, that it demanded amazing generosity to exist.

And here’s the kicker: we did it with our kind of humor; while the seders at home weren’t quite so riddled with errors, the strangely warm quality of our chaos felt the same. So it didn’t go perfectly—we have next year, the rest of our lives, to practice. Humor brings its own grace, but it always comes unpredictably. Don’t haggle or nitpick: just celebrate, hard, when it arrives.