‘Let Justice Roll Down Like Waters’

Lessons for 2020 from Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s 1963 address on religion and race

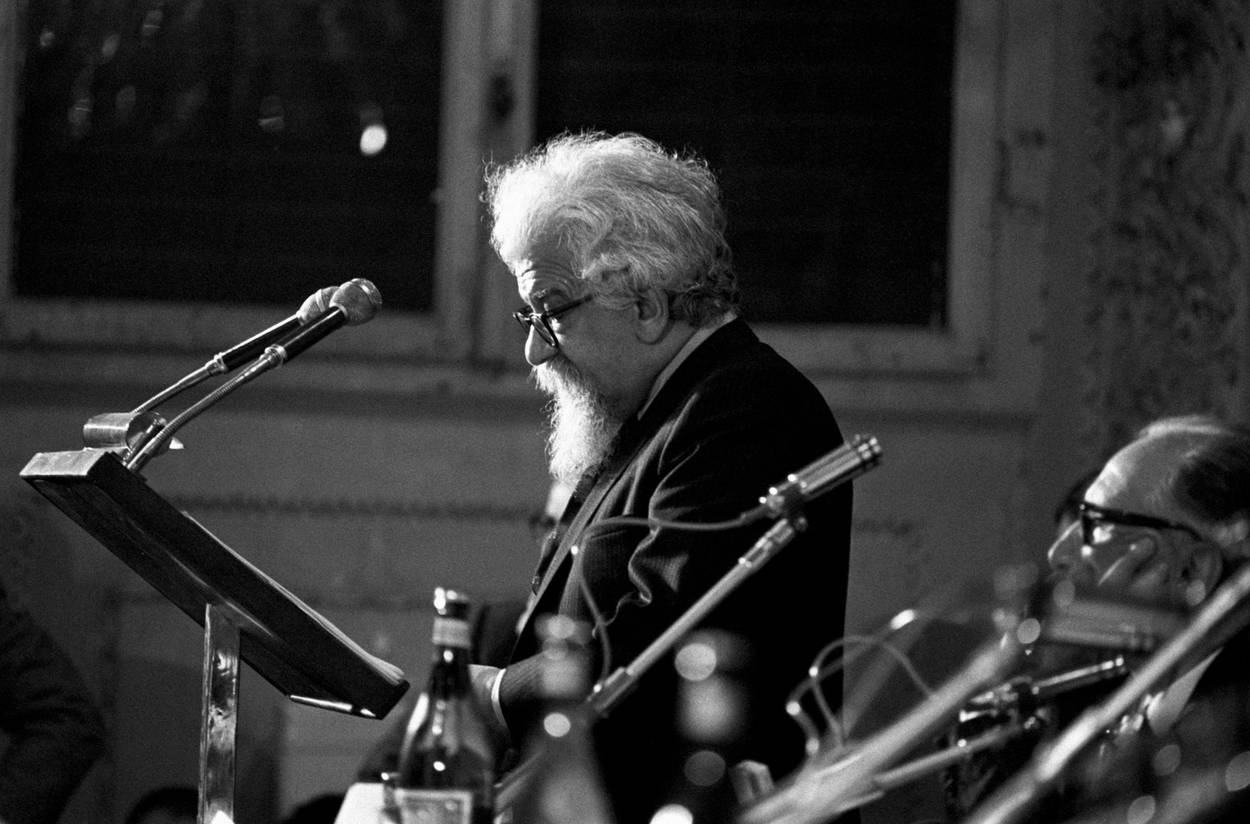

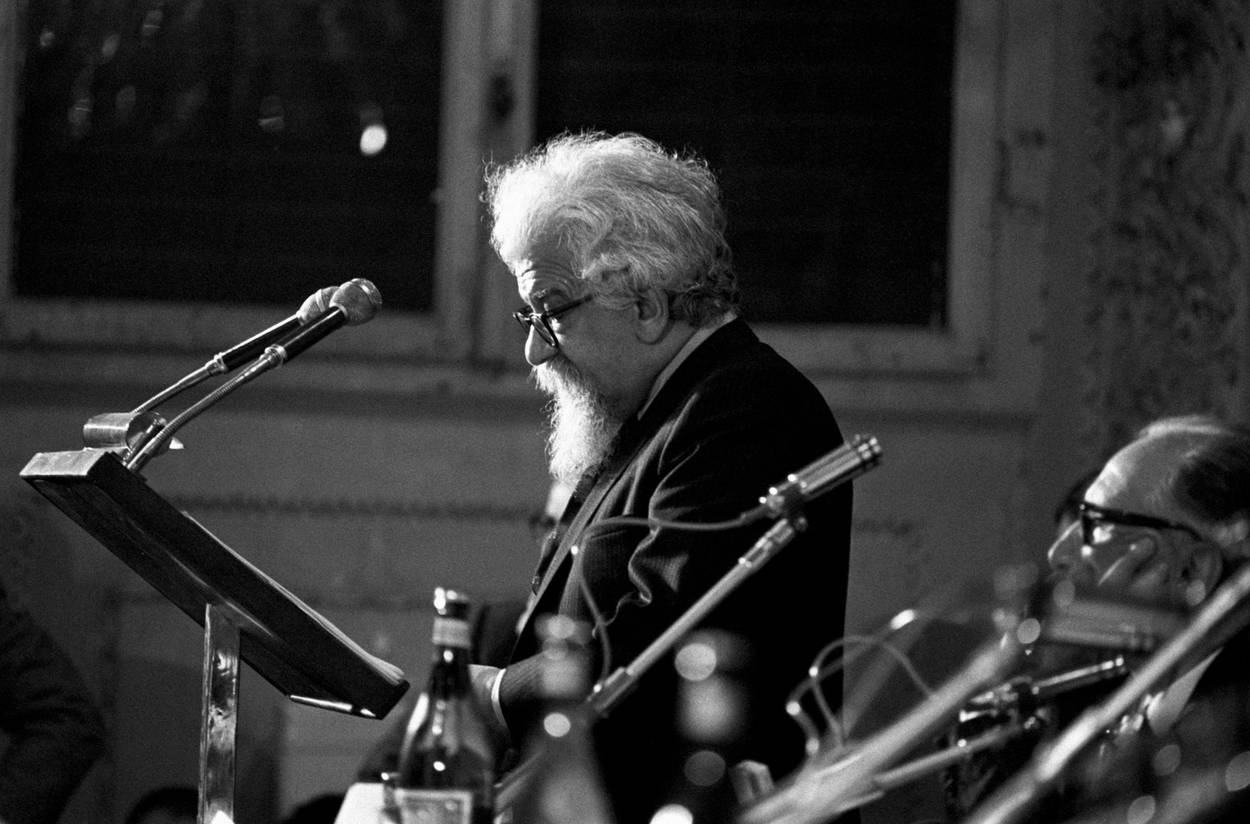

In January 1963, with the struggle for Black civil rights in full upswing, Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel delivered a groundbreaking address to the first ever National Conference on Religion and Race in Chicago.

It was a tense and tumultuous moment in American history: Debate raged over school integration, segregated public buses, and voting rights for African Americans. Heschel’s talk followed that of a young pastor from Georgia named Martin Luther King Jr., who had increasingly become the most recognized spokesperson for equality—propelled by his charismatic speaking style, his commitment to nonviolent protest, and his powerful, faith-based rhetoric. Yet King’s brand of activism was not universally applauded in the religious community. The civil rights leader and his concerns were seen by some Jews and Christians as too radical, and by others as outside the purview of religious life entirely.

Heschel—himself a unique mixture of mystic, philosopher, and activist, as well as a refugee from Nazi Germany—saw the conference as an opportunity to teach a Jewish lesson that would dovetail with King’s powerful Christian narrative, to dig deeply into the biblical and rabbinic traditions and pose questions such as: What would the prophets say about segregation? What does the Torah teach about racism? What does God demand of us in this moment? The resulting essay is a sweeping moral and religious argument in favor of social activism and of racial equality.

It was at that conference that Heschel and King met for the first time and began to develop a friendship that would strengthen both of their resolve. From there, they went on to influence one another’s writing and preaching, to support one another on important civil rights projects, and even to march side-by-side through the streets of Alabama.

In some ways, 1963 was a different time: before the Civil Rights Acts, before Affirmative Action, and long before the election of America’s first Black president. Yet, nearly six decades later, issues surrounding institutional racism are still very real, and the ideas that Heschel offers in “Religion and Race” still resonate.

Racism is a religious issue

In his essay, Heschel frames the issue of racism in powerful religious terms:

At the first conference on religion and race, the main participants were Pharaoh and Moses. Moses’ words were: “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, let My people go that they may celebrate a feast to me.” While Pharaoh retorted: “Who is the Lord, that I should heed this voice and let Israel go?” The outcome of that summit meeting has not come to an end … The exodus began, but is far from having been completed.

Heschel thus places the struggle for African American civil rights in a Jewish religious context: that of the exodus from Egypt. His basic argument is a familiar one today: Human beings are part of a single family, created in the image of God. Anything less than the full equality of all people is an abrogation of God’s will and a travesty to God’s very being on Earth.

He thus defines racism essentially as a form of idolatry—as the exaltation of petty human prejudices above God’s truth. At the same time he asserts that racism is a “disease”—one that affects “the spiritual substance and condition of every one of us.”

This dual definition of racism is important. Through it, Heschel asserts that the problem of racism exists in two spheres—the public and the private, the realm of social policy and the realm of individual bias/fear/privilege. Which means that it must be addressed in both spheres. It is not enough to outlaw hiring based on race, since employers’ decisions are shaped by unconscious prejudices. It is meaningless to declare “equal protection under the law,” as long as police officers and the African American community remain locked in a cycle—fueled by trauma, fear, power, and prejudice—that pits them against one another. It is premature to proclaim that our schools are integrated when Black and white students go home to such different neighborhoods, live with such different assumptions about themselves and their opportunities, and know so little about each other. These policy shifts must be accompanied by educational efforts, by training for law enforcement officers, by allocation of resources to address the deep traumas in the Black community, and by an honest individual accounting of each of our own personal biases—no matter how neutral or alert to injustice we think we are.

There can be no neutrality

By challenging us to admit our own prejudices, Heschel challenges the notion that one can be neutral in the face of racism. He argues in no uncertain terms that there can be no neutrality on this issue:

There is an evil which most of us condone and are even guilty of: indifference to evil. We remain neutral, impartial, and not easily moved by the wrongs done to other people. Indifference to evil is more insidious than evil itself. … An honest examination of the moral state of our society will disclose: Some are guilty but all are responsible.

Surely, when writing these words, he had in mind the crimes of Nazi Germany a mere 20 years earlier—in which whole segments of the population were systematically singled out for discrimination or destruction while so many stood by with feigned neutrality. Heschel drives home his point by drawing upon a halachic argument—found in the Talmud—that equates the crime of humiliation with that of murder:

“Bloodshed,” in Hebrew, is the word that denotes both murder and humiliation.

Thus, by the definition of Jewish law, a society that humiliates or mistreats its citizens is morally equivalent to one that murders. And for a citizen to live quietly, “neutrally,” in such a society is tantamount to being guilty of murder. This is one of the hard lessons of 2020: that the absence of active racism does not mean the presence of equality, since to do nothing is to preserve the status quo. Those of us (even within the Jewish community) who benefit from the privilege of being recognized as white have been—knowingly or not—perpetuating the deep racial divide in American society and the ongoing subjugation of the Black community. Knowing this calls for an active, anti-racist response to the current situation.

To act is not optional

Rabbi Heschel’s final call, then, is for teshuvah—for a societywide process of repentance and change:

We have failed to use the avenues open to us to educate the hearts and minds of men, to identify ourselves with those who are underprivileged. But repentance is more than contrition and remorse for sins, for harms done. Repentance means a new insight, a new spirit. It also means a course of action.

Would that these words were somehow less applicable today than they were in 1963. But they most certainly are not. Today, the problem of systemic racism still demands a sweeping and fulsome process of teshuvah in our society: an examination of the historical inequities, the resource allocations, the modes of training and education, the biases—both conscious and unconscious—that have led to the current situation. Not to do so would be an abrogation of our responsibility as citizens, as humans, as moral beings.

But even as Heschel exhorts us that this issue cannot be ignored, he reminds us that it can be solved, that “the greatest heresy is despair” and that the human capacity for goodness and for love is not to be underestimated. This hopeful message has resonance today as well, for in the midst of all the pain, the anger and the anguish, there is a real sense—perhaps more real than ever before—that change is possible. That the work is underway. That it is time to finally carry forward the task that was begun so long ago. Finally, let the passion of protest lead to lasting societal change. Finally, let words of hope be transformed into real equality. Finally, as the prophet Amos once wrote—and as both Rabbi Heschel and Dr. King were known to proclaim—“Let justice roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

Micah Streiffer is a rabbi, writer, musician and teacher based in Toronto. He serves as spiritual leader of Kol Ami Congregation in Thornhill, Ontario, and is the host of the weekly 'Seven Minute Torah' podcast.