How Not to Kill

On a popular app, Israelis and Palestinians tap into biblical wisdom with surprising results

This May, amid an awful flare-up of tensions, a small group of Palestinians and Israelis got together on the conferencing app Clubhouse to talk. Called simply Meet Palestinians and Israelis, the intimate gathering of friends and acquaintances quickly grew to a global meeting with over 500,000 participants over the course of two weeks. Actual Palestinians and Israelis—real-life people impacted by arguably the most watched conflict on Earth—shared their own stories and feelings as many others listened on. The group, Israeli-American rapper Rami Even-Esh wrote in Variety, was “the only place where individuals can have productive, unfiltered, solution-oriented conversations about such a difficult topic.”

We Americans are a fractured bunch these days, and in much need of new ways to have uncomfortable discussions. What, then, can we learn from this unexpected source, a Clubhouse group, about talking to, rather than past, each other?

The answer to that thorny question, like so many others, may very well be in the Bible, which urges us to distinguish between two fundamentally different ways of being in the world: Cities of Moses and Cities of Cain.

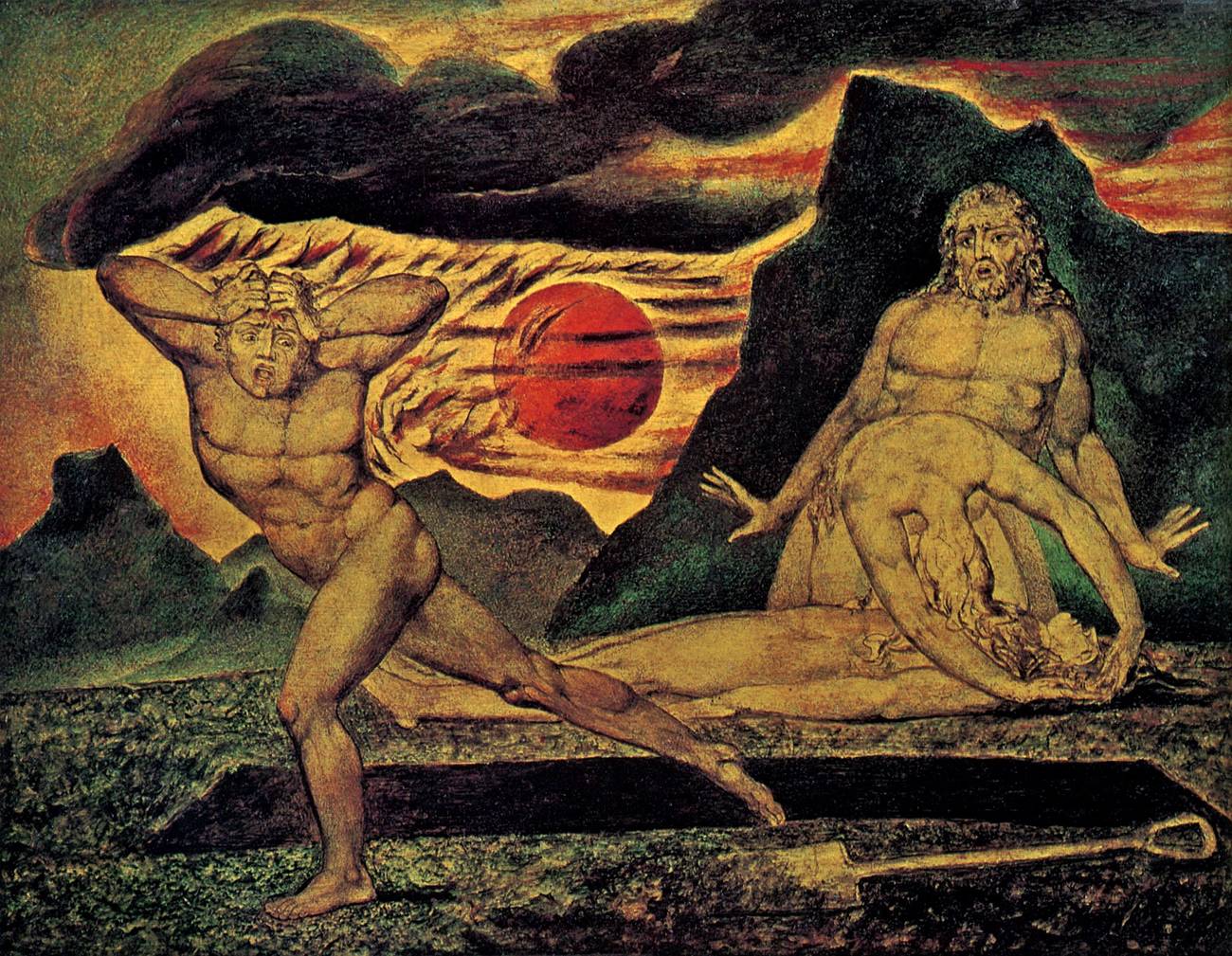

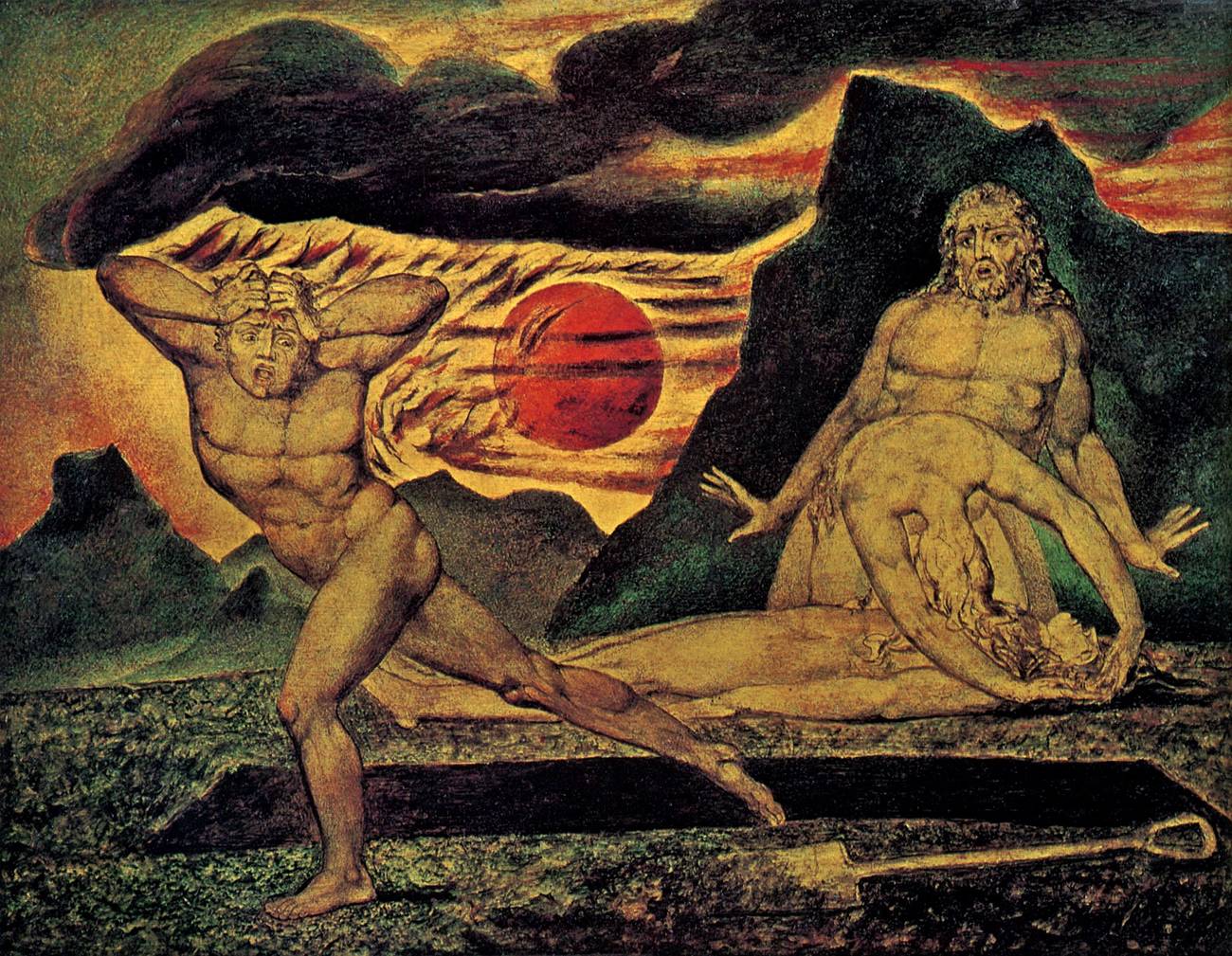

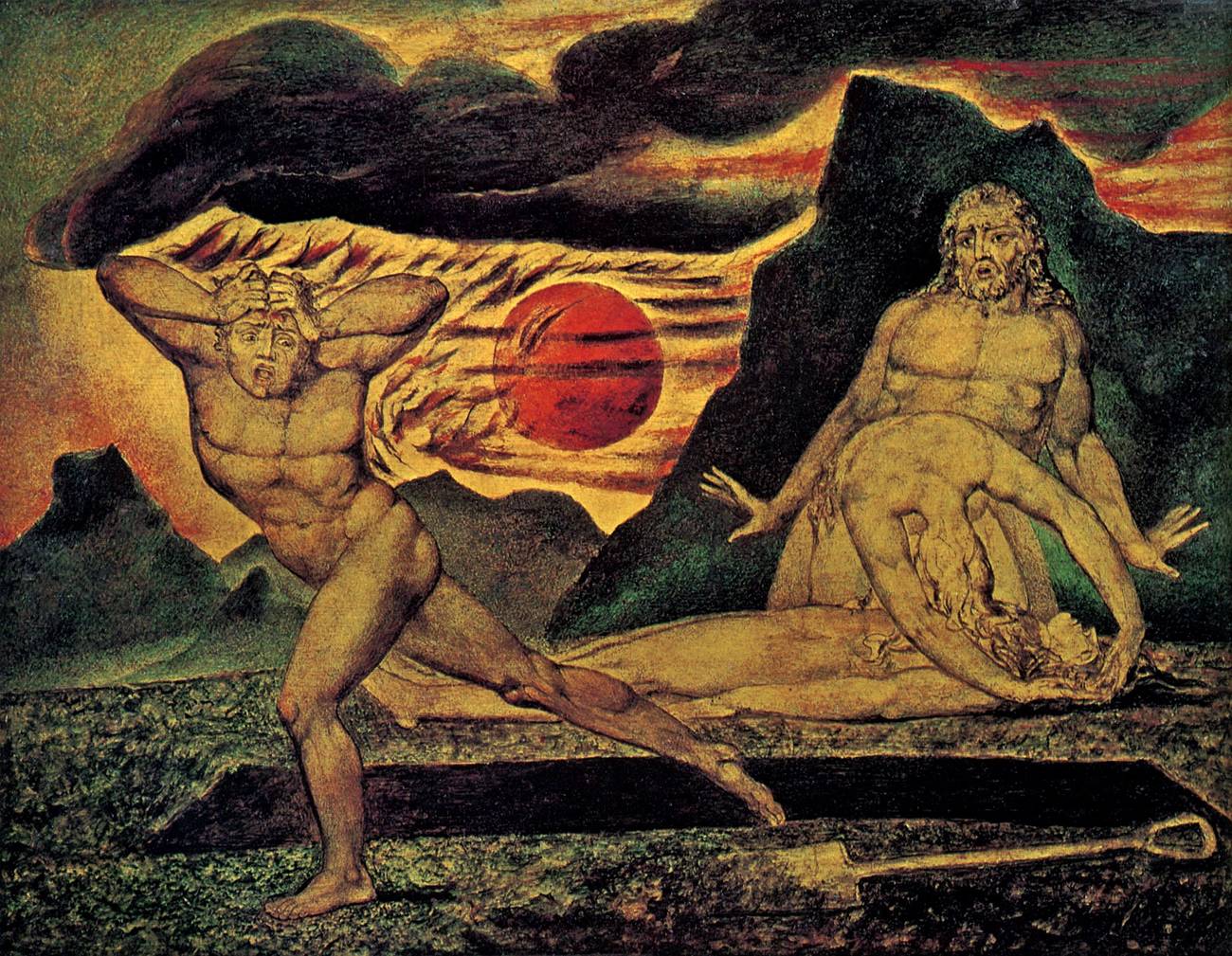

If you are even mildly familiar with the book of Genesis, it’s likely you know the first part of Cain’s saga, which ends with history’s first and still most famous murder. What you may not know of, however, is Cain’s second act: Cain creates the Bible’s first city.

In biblical terms, that the Bible’s first killer would make the Bible’s first city makes a great deal of sense. Throughout the Tanach, cities are depicted as strongholds shut off from the outside, ideally, as Deuteronomy instructs us, “fortified with high walls, gates, and bars” to protect those inside from the dangers beyond. And Cain, of all people, knows well the dangers that lurk out in the open. The same verse in which Cain kills Abel specifically mentions that the murder took place when they were in the field. Of course he would want to shut that danger out, and keep his new family in.

The problem is that shutting the violence out doesn’t work. The last we hear of Cain’s family is from Cain’s descendant Lamech, who, wouldn’t you know, murders a guy who bruised him. The message couldn’t be clearer: Try shutting the gates and leaving the horrors outside, and you’ll soon learn that the violence was coming from within all along.

While Cain slays his brother and walks away, Moses takes a very different approach, demanding that the innocent search their souls at the scene of the crime.

Enter Moses. Like Cain, the great prophet, known in Hebrew as Rabeinu—our teacher—also kills a man. But while Cain slays his brother and walks away, Moses takes a very different approach, demanding that the innocent search their souls at the scene of the crime.

As the Children of Israel prepare to enter the Land of Israel, Moses readies them for the great responsibility that comes with the great power of sovereignty. Should someone be murdered and his body left in the field, Moses thunders, and the identity of the killer is unknown, the people must collectively take responsibility for the bloodshed by performing a complex and bloody ceremony:

Your elders and magistrates shall go out and measure the distances from the corpse to the cities nearby.

And the elders of the city nearest to the corpse shall then take a heifer which has never been worked, which has never pulled in a yoke. And the elders of that city shall bring the heifer down to an ever-flowing wadi, which is not tilled or sown. There, in the wadi, they shall break the heifer’s neck …

The priests, sons of Levi, shall come forward; for the LORD your God has chosen them to minister to Him and to pronounce blessing in the name of the LORD, and every lawsuit and case of assault is subject to their ruling.

Then all the elders of the town nearest to the corpse shall wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken in the wadi. And they shall make this declaration:

“Our hands did not shed this blood, nor did our eyes see it done. Absolve, O LORD, Your people Israel whom You redeemed, and do not let guilt for the blood of the innocent remain among Your people Israel.”

And they will be absolved of bloodguilt. (Deuteronomy 21:1-8)

What is the meaning of this gory ceremony? Perhaps it is a rejection of the worldview of Cain.

When Cain murders Abel, God asks Cain where Abel might be. “I do not know,” Cain responds, and then, famously, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” To which God fires back, “Your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground.” Cain goes on to leave the scene of that blood, turn his back on the open ground, and hide away in his cloistered city.

Moses, on the other hand, tells his followers to do precisely the opposite: Exit the city and return to the field, to the scene of the crime, to the spilled blood on the ground. He doesn’t want them to be, like Cain, in a state of perpetual denial; he wants them to accept responsibility because they are, as we are all, their brothers’ keepers.

According to Rashi, this call to accountability is even more far-reaching. After all, Rashi asks, “would it enter anyone’s mind that the elders of the court are suspect of shedding blood?” Instead, Rashi suggests, “the meaning of the declaration is: We never saw [the victim alive in our city] and knowingly let him depart without food or accompaniment.” We never turned a blind eye to his needs in a dangerous world.

The ritual holds the city elders—paragons of virtue and justice—accountable for the crime that occurred near to their city’s limit because perhaps they have allowed a culture of negligence to flourish, and that negligence may have allowed that violence to happen. Cain, in other words, might have asked “Am I my brother’s keeper?” but in Moses’ world, even asking the question is never an option.

The differences between Cain and Moses don’t end there. Even after God offers him a lesson in personal responsibility, Cain remains silent and sullen. We can feel his seething resentments—against his brother, who bests him, and perhaps even against his mother and father, Adam and Eve, so conspicuously absent from his life’s story. How will he resolve all of his issues? How will he address his rage?

The Bible answers this question with a master class in drama. Here’s Genesis 4:8:

Cain said to his brother Abel/and when they were in the field, Cain set upon his brother Abel and killed him.

Cain opens his mouth. He’s about to speak. And then, suddenly, jarringly, he’s cut off. Mid-verse, the story switches to the murder. When words fail us, the Torah teaches, violence ensues.

Moses knows this, which is why he does not allow the elders to remain silent. They make a pronouncement. They do so in the presence of the priests—the caste that, we are told, oversees every lawsuit and case of assault: whose role is to arbitrate the difficult conversations and to address the moments when those hard conversations explode into something worse. And the ritual itself isn’t a stand-alone performance, but part of an entire construct of laws that recognize that men are everywhere inclined to be wild and murderous, and therefore must be steered by a culture that obliges them to temper their anger by listening to and engaging with others in ways that help mitigate their rage and reduce the chances of more lives lost.

You hardly have to be a rabbi to see how these ideas apply to us today. And it starts with re-understanding what God first told Cain. The beast of wrongdoing, the Almighty warned Cain, always crouches at the door. Poor Cain took this bit of divine warning a touch too literally, imagining a demon to be shut out and a door that could be slammed shut and protect those inside. Instead, he ended up trapped alongside his seething anger, killing his brother in a fit of jealousy. God, the rabbis explain, had meant for Cain to realize that because the beast—our basest, cruelest instincts—never goes away, our only choice is to become its master and get it to heel, which, sadly, requires engaging with it right on. To master the beast, you must look into the private and dark corners of your soul—to get the strength to fling the door wide open.

That soul-searching and door-opening is the basis of the City of Moses—then and now. “It is an extraordinary thing,” the writer Dahlia Lithwick observed of her experience on the Israeli-Palestinian Clubhouse group, “that technology—‘it’s just code’ someone said—allows a room of 900-plus listeners to come together with gifted, empathetic moderators, across security fences and checkpoints and oceans and generations to talk.”

Of course, that same code is the foundation of the echo chambers we build around ourselves every day, the Facebook groups and TikTok accounts we flock to in order to shout our darkest opinions and see them confirmed by people who feel and think just as we do and who share our suspicion that others, those outside the walls of our gated virtual community, are only there to hurt us. The infrastructure of the city of Cain is identical to that of the City of Moses; only the morality we bring to those spaces has the ultimate sway in deciding what sort of city we inhabit.

The City of Cain is a moral tragedy. The City of Moses is a transformational possibility. But, as those Israelis and Palestinians on Clubhouse teach us, it’s possible to transform the one into the other. To leave the City of Cain behind and move on to a City of Moses, we need to be ready to do something that is perhaps harder than merely tinkering with the doors, or changing the technologies that create them. We need to be willing to unlock those doors, walk outside, and finally encounter each other—by finally facing ourselves.

Abe Mezrich is a Jewish poet and software marketer, and author of the collection Between the Mountain and the Land Lies the Lesson.