How to Pray in a Plague

Three times a day, Jews are asked to do something very difficult and essential to our well-being

The other day, a good friend whose relative lay dying of COVID-19 in a New York hospital told me something that shook me to the core.

“You know,” he said, “I’m having trouble lately finding any kavannah.”

Kavannah, as any observant Jew will tell you, means purpose. It’s the intentionality we’re commanded to muster when praying three times daily, real and true and unmitigated gratitude to God for all His bounty. And if my friend, a rock of quiet faith, couldn’t hack it, even in a time of a plague, I thought, we’re in trouble.

This thought didn’t make praying any easier. As a lifelong modern Orthodox Jew, much of my religious observance is relatable to those outside my sliver of Judaism. I only eat certain foods, like vegans. I observe Shabbat while The New York Times and Emmy-nominated filmmakers encourage “tech Shabbats,” preaching of the restorative power of unplugging one day a week. Others find their spiritual cleanses in silent retreats or meditation apps. While some readers seek happiness in Aristotle’s Way and contentment in the verses of first-century Roman poets, I turn to the stories of Abraham’s journeys and David’s Psalms for succor. But what sets my daily life apart from that of so many others is my practice of praying. And it is a rather mysterious ritual, even to its devoted practitioners.

For thousands of years, Jews have argued about this strange practice. How does it work? Doesn’t it come across as pretentious to “praise God”? Can we update ancient verbiage for more modern accessibility? Do our requests really sway God? Won’t it feel like having a one-sided conversation some, most, or even all the time? And if we can’t focus, or have kavannah, for the entirety of the sometimes-lengthy services, what are the most important parts, where mindfulness is mandated?

The talmudic rabbis weren’t even sure when the practice of praying three times a day was established. One ancient scholar suggested the prayers correspond to the schedule of animal sacrifices conducted daily in the Temple. Another argued that we pray three times a day because each of our three forefathers—Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob—each established a prayer of his own: Abraham while looking out over Sodom, whose citizens’ deaths he had tried and failed to prevent; Isaac while venturing to the field in the afternoon, a solitary figure longing to connect with someone who could comfort him over the loss of his mother; and Jacob in the evening alone on a mountain, pillowed by rocks, uncertain what his future held. These were prayers of isolation, of distance, of loss, of precariousness. They’re also a heck of an example to follow.

How, then, are we supposed to pray? The rabbis could mostly tell us what not to do: “One who makes his prayers set,” Rabbi Eliezer says in the Mishna in Tractate Brachot, “those prayers are not proper supplications.” In other words, if you think that simply following the motions and reading the words on the page is enough, forget about it.

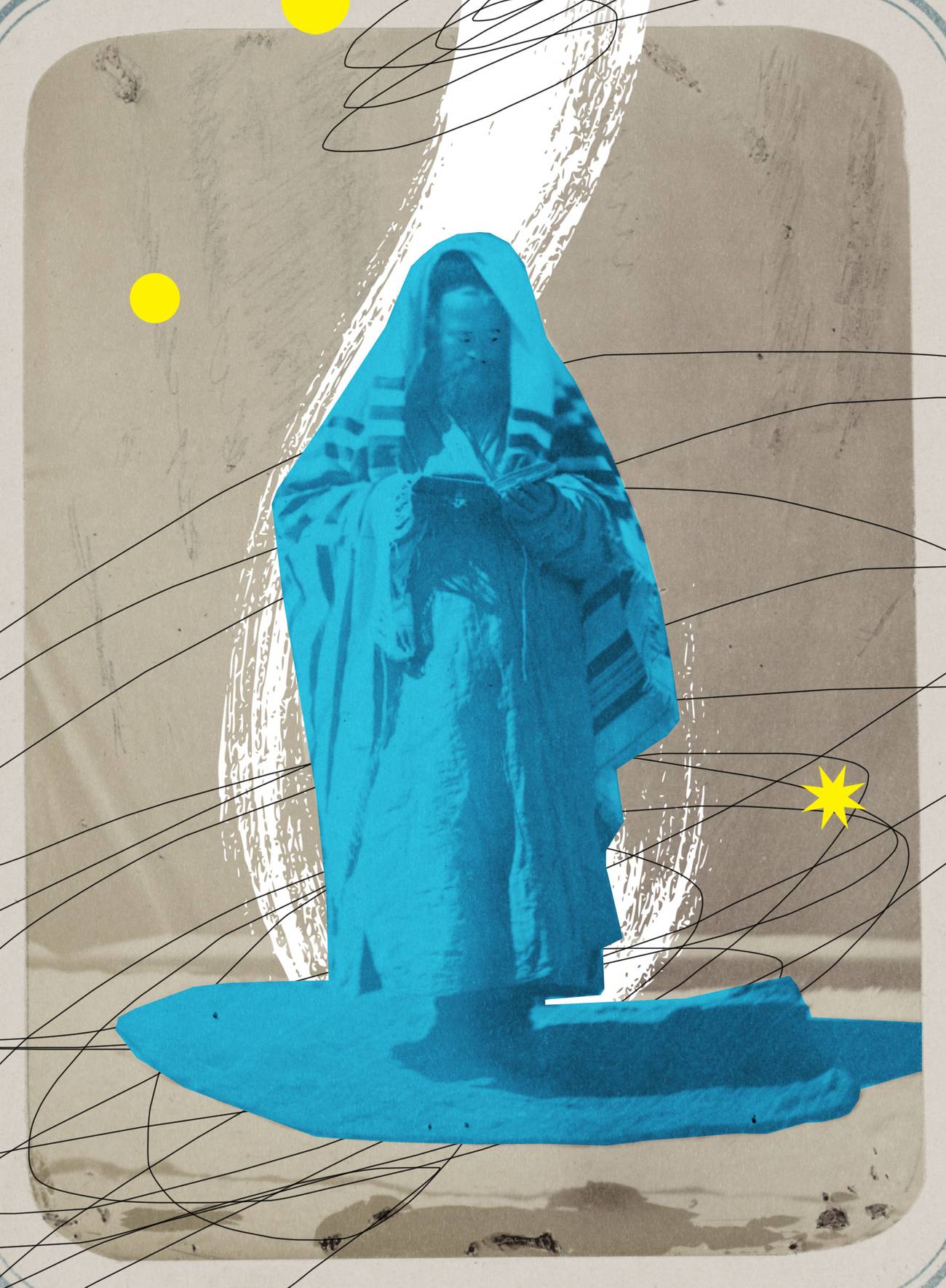

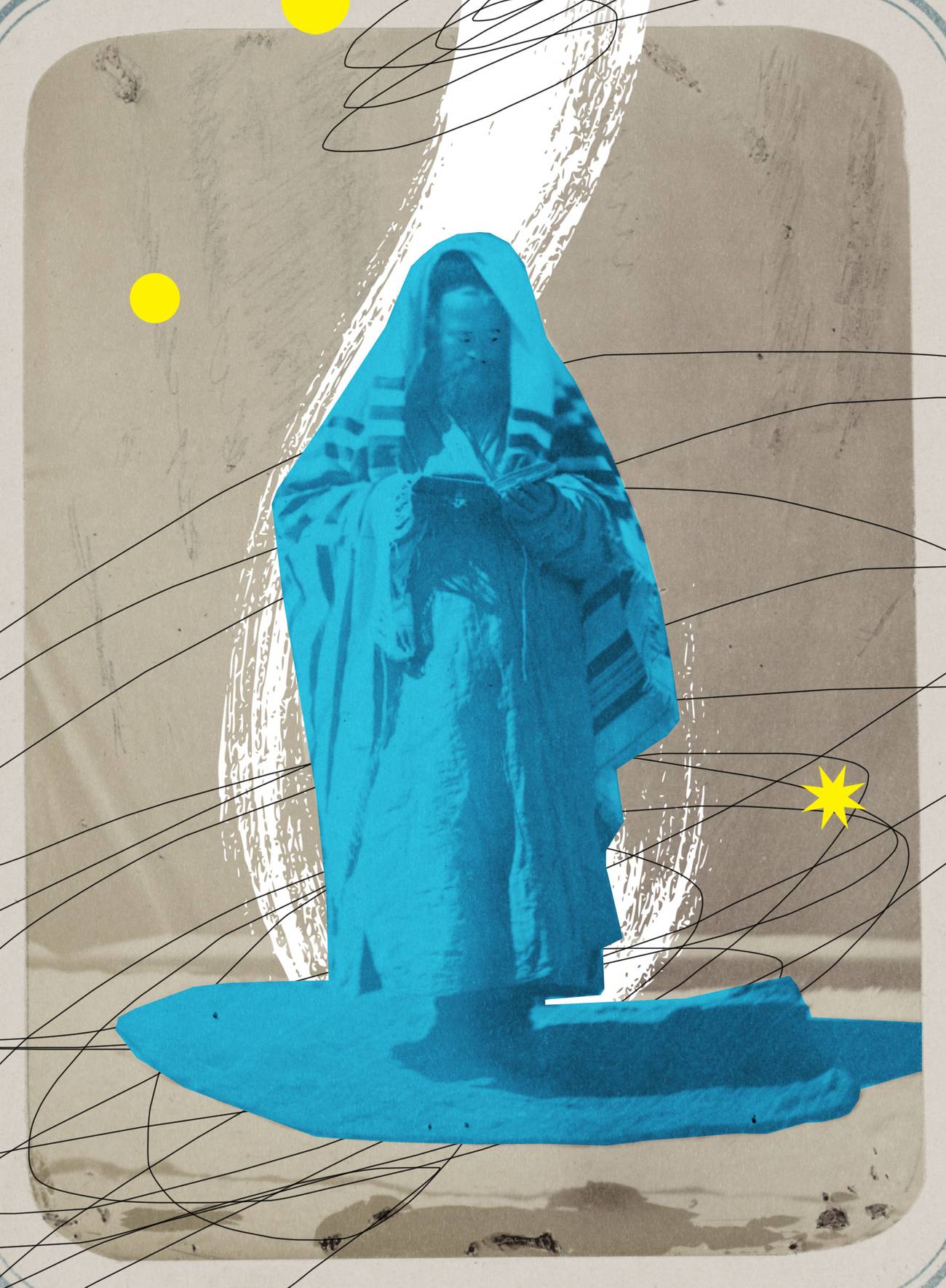

Maybe that’s why so many of us sway back and forth as we pray, as if a bit of motion could quell all that insecurity about prayer, or as if the movement was some sort of physical manifestation of the inherent anxiety of the whole enterprise, a reminder that no matter how hard we try, we can never get too close to God.

That realization is difficult enough under the best circumstances; when considered in the midst of a pandemic—with more than 40,000 dead and tens of millions unemployed in this country alone—it can be downright depressing. But if we ask ourselves seriously and candidly, as my devout friend had, how we should go on and find kavannah in these dire times, the answer may surprise—and comfort—us.

“The basic function of prayer,” the celebrated Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik wrote, “is not its practical consequences but the metaphysical formation of a fellowship consisting of God and man.”

Each morning, I wake up and rather than succumb to my instinct and rush to my inbox or to the coffee maker or to the newspaper on my front door, I stop. For 40 minutes, I try to get into a space outside of all other spaces. I put aside all thought of the calculus of lives lost or careers furloughed, and try instead to thank the Creator for all His kindness to the world and me, for this gift of life, for one more day with my wife and my children.

It’s not easy. But it was never meant to be: Standing alone, praying to a supreme being you can’t see and who does not talk back is an exercise in transcending our ego and the other boundaries that hold us back. Sometimes this exercise leaves us feeling drained and exhausted. Sometimes our mind can’t fly above the stream of earthly troubles. But when it can—maybe four times out of 10, still the sort of average that would get you into the Baseball Hall of Fame—everything changes. To find kavannah is to understand what Rav Soloveitchik was talking about when he rhapsodized about that metaphysical fellowship between Man and God. To find kavannah is to realize that every morning is a new act of creation, and that, like Adam, we are now God’s partners in this miraculous act, called upon to be the best we can be and avoid succumbing to our baser instincts, from sinking into depression to wasting our time raging at strangers on Twitter. Prayer, even—or especially—in a plague, can still calibrate our souls and guide us through our anxiety, taking us from muddled to mindful.

If all this sounds a bit too lofty coming from a religious person, the same exact insight also comes in other flavors: Recently, everyone from Harvard professors to TED Talks discovered the psychologically fortifying power of expressing daily gratitude for even the smallest of gestures. An internationally newsmaking study showed how such a practice could even save your life. Thousands of years before these insights were offered, our patriarchs and priests had already set this engine of well-being in motion by commanding us to pray.

And pray we should. There’s hardly a better way to find balance and purpose, especially during a plague. Some of us will do it by putting on tefillin and a tallis and reciting the ancient Hebrew words of praise and gratitude to God. Some of us will opt for less traditional, more personal variations on the same theme. But all of us can benefit from joining my friend in his foundational struggle, the struggle to train our hearts on other, higher plains. If the siddur isn’t your jam, maybe you’ll find a bit of inspiration in the words of another religious man who contemplated the correlation between well-being and prayer, John Milton, who imagined God’s intent in creating Adam thus:

Created in his image, there to dwell

And worship him, and in reward to rule

Over his works, on earth, in sea, or air,

And multiply a race of worshippers

Holy and just! thrice happy if they know

Their happiness, and persevere upright!

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada, which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, Esther in America, Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth and Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.