Impure Thoughts

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study, the practical-minded, hyperspecific, sometimes contradictory rules of Jewish ritual purity. Plus: Why religious uncleanliness is like a virus.

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

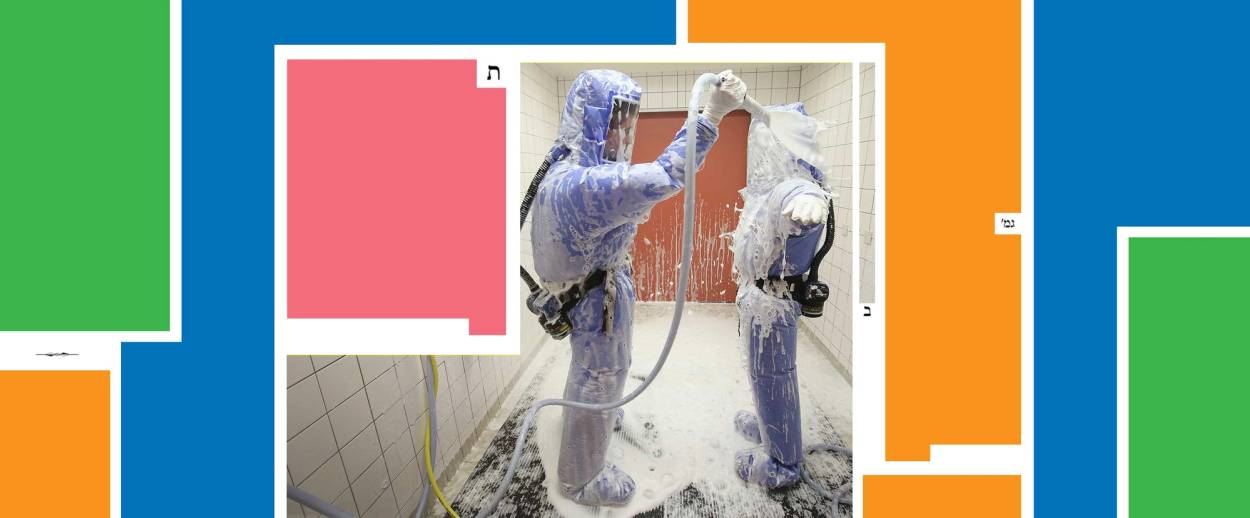

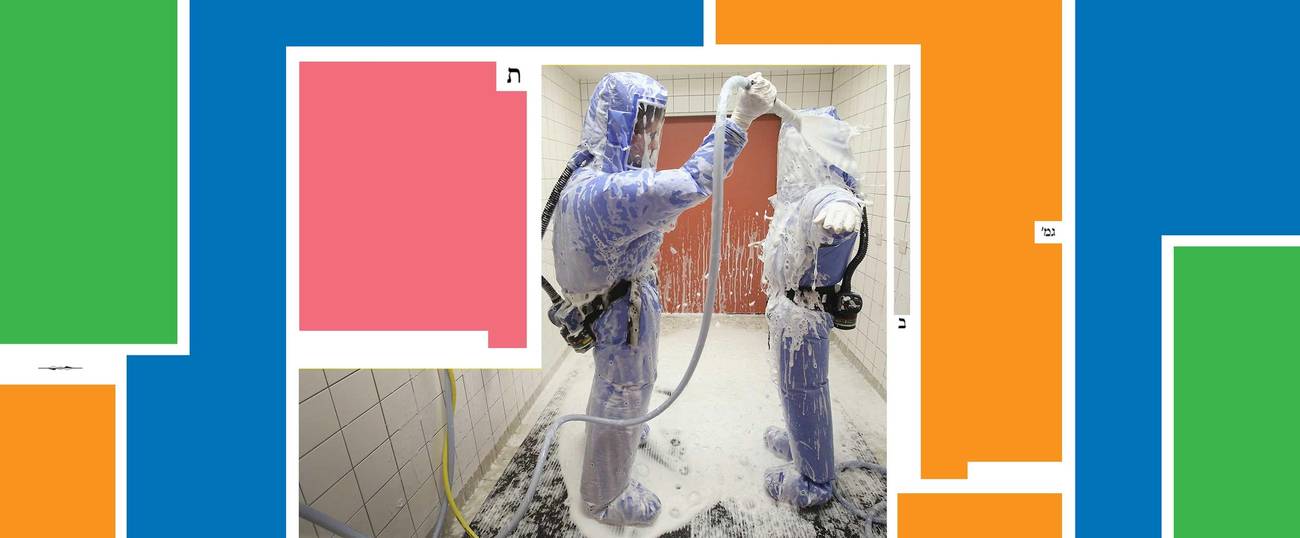

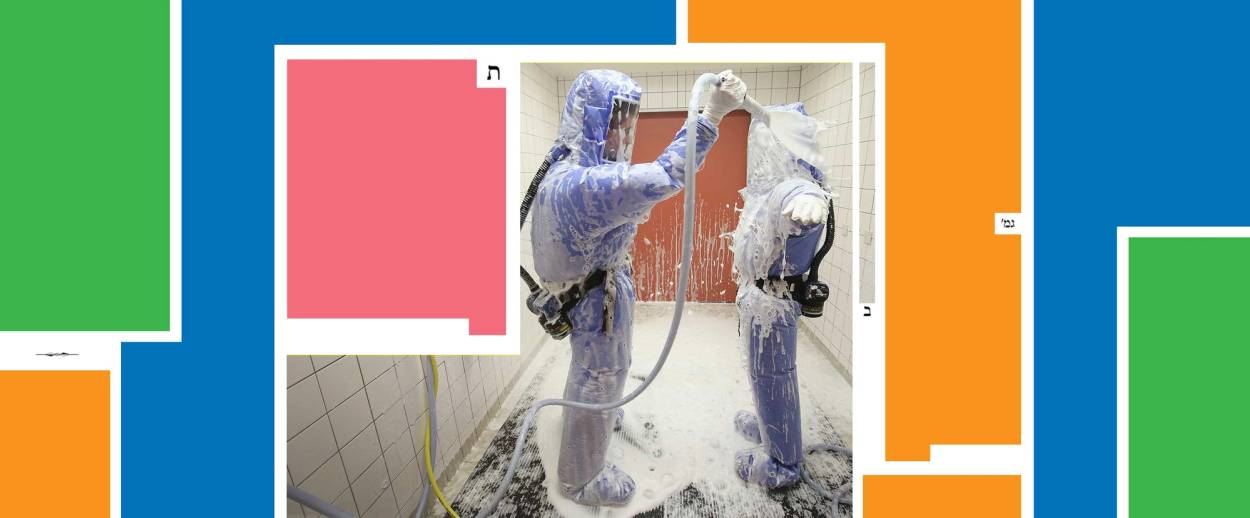

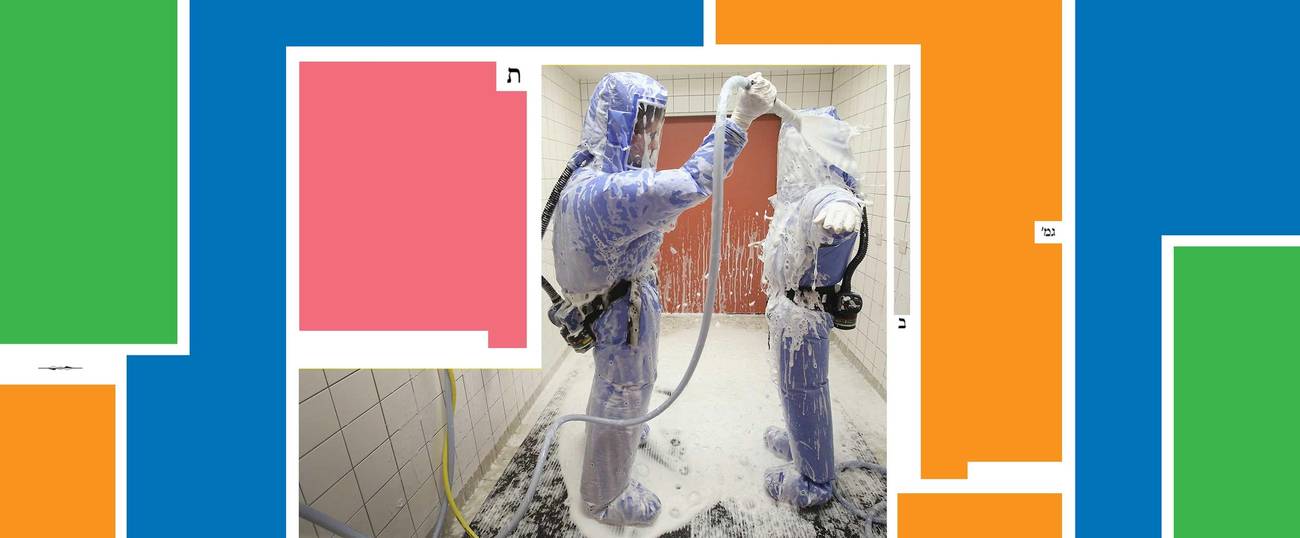

One of the most important subjects in the Talmud, in terms of the sheer quantity of attention devoted to it, is ritual purity. Yet purity, taharah, and impurity, tumah, are among the Talmudic concepts that make least intuitive sense today. They are not moral concepts but taboos that originate in a superstitious dread of contamination. An assortment of apparently unrelated people and things—including corpses, lepers, menstruating women, men who have had a seminal emission, and certain kinds of lizards—are defined in the Torah as bearers of tumah. You can contract it by touching them or, in some cases, even just being under the same roof with them.

Perhaps the best modern metaphor for tumah would be a virus: It is invisible to the naked eye and can be transmitted through touch, food, or cooking utensils. Its effects are serious: Depending on the type of tumah, a person who had it could not share food or housing with other people, have sex, enter the Temple, or perform priestly rites. Fortunately, there are ways to cure tumah. Vessels can be boiled or broken, lepers can shave their hair, women can immerse in a ritual bath. For the worst kind of tumah of all, the kind that comes from a corpse, the only cure was a ceremony involving the ashes of a red heifer.

Today, most of the laws of purity are moot. (The exception are the laws governing menstruation and sex, which are still practiced by Orthodox Jews.) In the absence of the Temple there is no way for tumah to be purged, so technically, over the last 2,000 years, all Jews have become tamei in one way or another. This makes taharah and tumah one of those Talmudic subjects—like the laws of Temple ritual or animal sacrifice—that have to be studied for their own sake, rather than for the purpose of practical implementation. It is completely abstract, yet the subjects it deals with could not be more concrete: Talking about tumah means talking about corpses, sores, blood, semen, and chunks of meat.

A good example came in this week’s Daf Yomi reading, in Chapter 9 of Tractate Chullin. In a sense, this chapter is an anomaly in the tractate, which deals with animal slaughter rather than the laws of purity. But when you slaughter an animal you’re left with meat, and meat is one of the things that can become impure if it makes contact with a source of impurity. The general rule is that a piece of meat can only transmit tumah if it is the size of an egg-bulk. (Talmudic measurements of small volumes are based on foods: Things can be a bean-bulk, an olive-bulk, or an egg-bulk in size.)

The question asked in the mishna in Chullin 117b is how you define an egg-bulk of meat. Does it have to be all meat, or can it include other things that are often found with cooked or uncooked flesh? For instance, say you have a lump of meat attached to a piece of animal hide, or stuck to a bone—do those substances count toward the egg-bulk measurement? What about gravy or spices in a stew?

The mishna gives a double answer. For the purposes of food impurity, these things do join with meat to create the necessary measure. If you have a scrap of meat attached to a femur, for instance, the whole thing can become impure, since together they are greater than an egg-bulk. But for the purposes of carcass impurity, they don’t join together. The difference between meat that is food and meat that is a carcass has to do with how the animal died: If it was slaughtered in kosher fashion it is meat, while if it died of disease, or was killed in a nonkosher way, it is a carcass and must not be eaten. In effect, then, there is a higher standard for food impurity than for carcass impurity: “The Torah included certain items to impart impurity of food beyond those which it included to impart impurity of animal carcasses.”

The Gemara’s discussion of this point turns out to be extraordinarily lengthy and complicated. First, the rabbis ask about the scriptural basis for the notion that bone or claw or tendon can join with meat to make up the required measure. This is not stated explicitly in the Torah, so where does the mishna get the principle from? The answer is that it is implied by a verse in Leviticus, where the Torah teaches that “any sowing seed that is sown” can contract tumah. A seed that is sown in the ground, the Gemara points out, has a covering, a shell or husk that protects the grain. It follows that an item’s covering or protection is included with the item itself when it comes to contracting impurity.

However, Rabbi Yehuda teaches in Chullin 118b that this principle only applies to the first layer of protection, not to a second layer—the covering of a covering. He uses the example of an onionskin, which according to Yehuda has three layers or peels. The innermost peel counts as part of the food itself, and the middle peel counts as the covering of the edible part; but the outermost peel is a covering of a covering, and so it does not transmit tumah.

Translated into animal terms, this clearly means that an animal’s hide should be counted toward its measurement for purposes of tumah, since it is a covering of the flesh. But what about its hair? The hair grows on top of the hide, so in a sense it is a covering of a covering of the meat. Does it also count toward the measurement for impurity? Surprisingly, Reish Lakish says it does: If you touch the hair of an animal carcass, you contract tumah. This is because, the Gemara explains, while it may seem that hair sits on top of the hide, it actually “penetrates through” the hide, so that the base of the hair touches the animal’s flesh. That means it is itself a covering, not just the covering of a covering.

This statement, however, prompts an objection from Rav Acha bar Ya’akov, based on an entirely different issue. The scrolls of tefillin are made of parchment, which is dried and treated animal hide. Now, if it is true that an animal’s hair grows through its hide, then parchment would be porous—it would have countless tiny pores where the hairs grew. But “Don’t we require phylacteries to be written with a perfect writing?” asks Rav Acha. If there were perforations in the parchment, then the letters wouldn’t be “perfect” but would contain lots of little holes.

Happily, there is an answer to this objection, “which they say in the West”—that is, in the Land of Israel, which was west from the point of view of the Babylonian rabbis: “Any perforation over which the ink passes and which it covers is not considered a perforation.” In other words, the pores in parchment are so small that they are invisible through the ink, so they don’t count. As abstract as Talmudic reasoning can be, the rabbis know that in the end, the law must respect the practical needs of Jewish life.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.