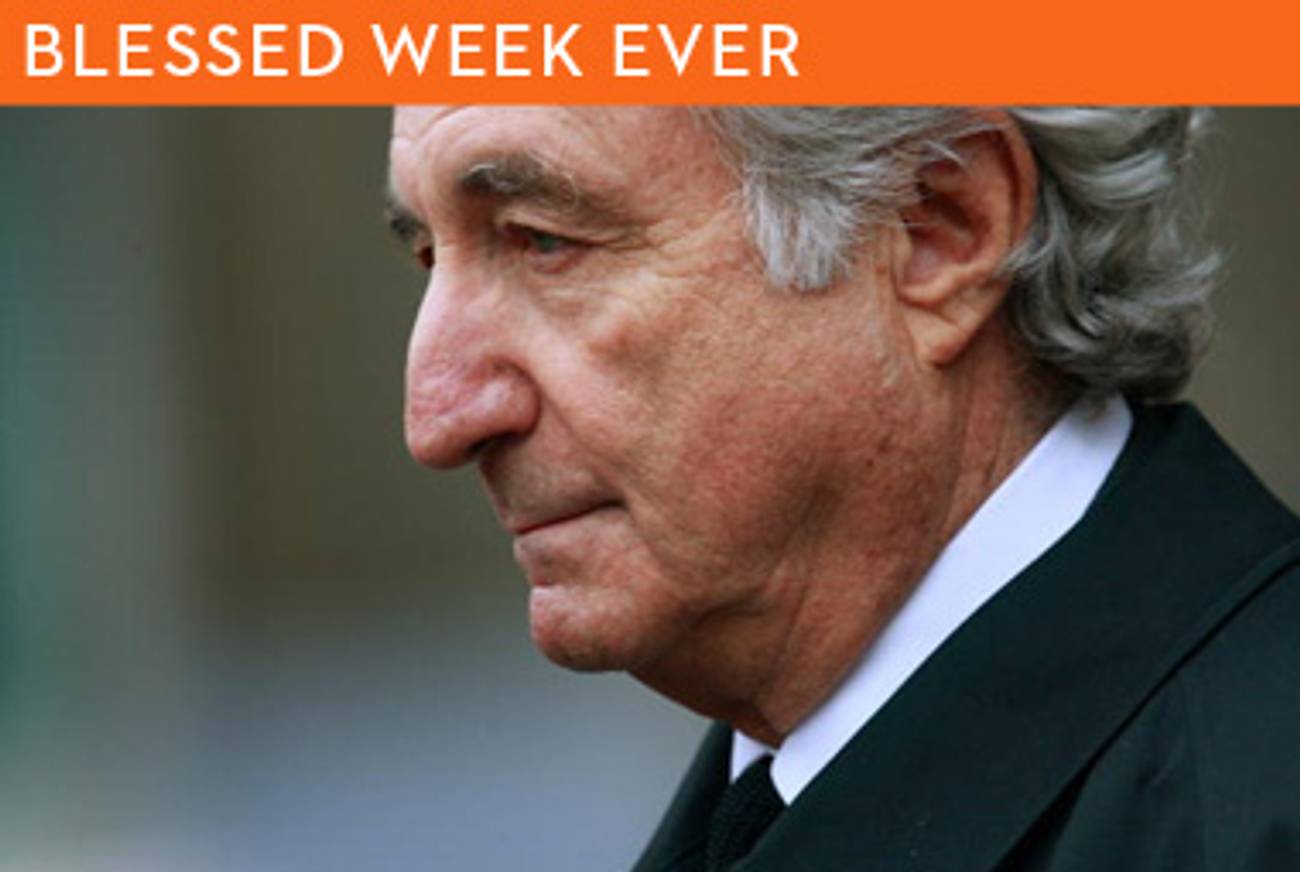

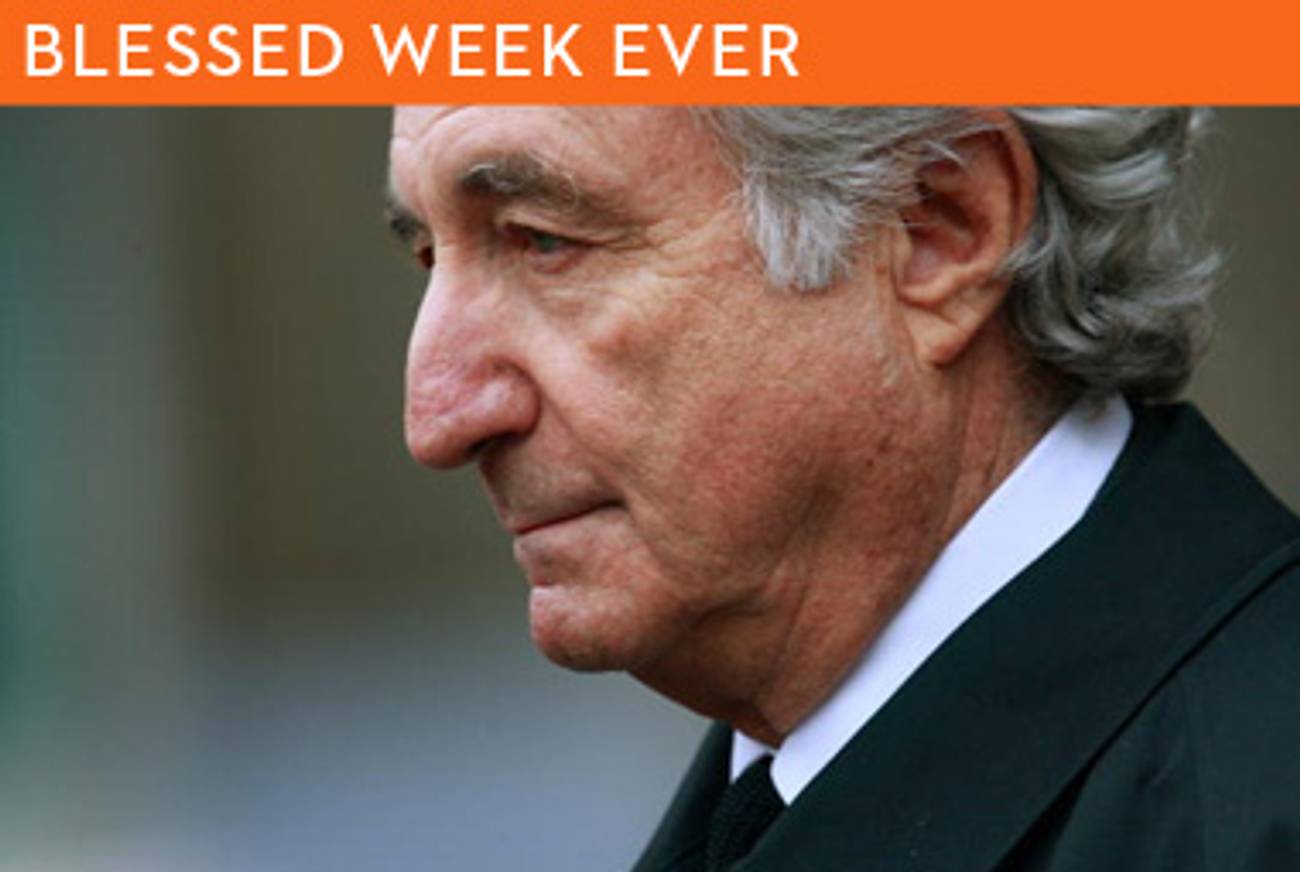

In Defense of Bernie

Like Moses, who staked his place in history to defend his people after the Golden Calf debacle, Madoff, too, realized that the true value of money isn’t always what it seems

As a young boy growing up in a fairly traditional Israeli family with a rich rabbinic history, I was raised to see the Bible’s heroes as history’s ultimate good guys. For the most part, this wasn’t a problem. Any kid, after all, can dig David the giant-slayer, secretly wish he could talk to animals like Solomon the wise, or read in awe about Abraham’s knife-wielding blind faith. But I never understood Moses. Moses made no sense.

This week’s parasha provides a good example of the man’s strange nature. Moses climbs up to the mountain to receive the word of God, tarries in returning, climbs down, and sees the Golden Calf. Reading the story as a child, I was incensed on his behalf: Having just witnessed the true spirit of God, I asked myself, the Israelites couldn’t even give Moses the benefit of the doubt for running a bit behind schedule? Are a few weeks truly that much of a setback that a nation that had just been awarded the Torah would resolve to break the divine rules and erect a shining statue? And, most troubling of all, what to make of Moses’ own baffling response? Rather than fume at the ungrateful idolaters, Moses wrestles with God on their behalf. The supreme being is in a genocidal state of mind; bravely, Moses takes a stand and demands that God spare the Israelites. “If you do not forgive them,” he tells the Lord, “blot me out from the book that you have written.” Why go through all that trouble, risking anonymity in perpetuity, to protect a sinful horde?

Just ask Bernie Madoff.

The disgraced financier is not a man usually associated with biblical wisdom, but a series of recent disclosures, including interviews with Madoff himself, suggest that he and Moses might have shared a fundamental understanding of the human condition. Speaking to a reporter from the New York Times, Madoff argued that the various banks and financial institutions he’d defrauded were guilty of “willful blindness,” and that there was no way these large and savvy investors—as opposed to private individuals—did not know his unnaturally profitable operation was a sham.

Some newly released documents support Madoff’s claim. Earlier this month, for example, internal communications of JPMorgan Chase employees were made public in a lawsuit, indicating that some at the bank were suspicious of Madoff long before he was arrested. On June of 2007, a senior executive at the bank, the Times reported, sent an email to colleagues and said that another executive at Chase “just told me that there is a well-known cloud over the head of Madoff and that his returns are speculated to be part of a Ponzi scheme.”

Much of Madoff’s recent statements, of course, are self-serving, an attempt, perhaps, to lessen the effect of his grievous actions. But there’s much more we can learn from his comments that the banks were somehow complicit in his crime: What Madoff understood, the fundamental truth lying at the heart of his deceptions, was not that people are greedy, but that people would go to tremendous lengths to try and overcome the basic unknowability, the profound impermanence that is at the core of human existence. People invested with Madoff because he suggested that he could turn the market—tempestuous, unpredictable, sometimes vengeful, frequently wild—into a tamed beast that behaved just as you liked it to behave, a reliable animal that gave and gave and asked for nothing in return. And the banks collaborated not only because great wealth was being generated, but also because Madoff’s fantasy was too strong to resist.

It’s the same story, essentially, as this week’s parasha. As the story begins, the Israelites are introduced to God, a mysterious and invisible being that presents them with rules but is never entirely familiar to them. They are awed, but their awe soon turns to anxiety. Like the Wilpons and the Picowers and Madoff’s other victims, they needed something permanent, something they could grasp, something controlled and controllable, something so unlike God. They ask for a calf, and Aaron, the great priest, doesn’t hesitate for a moment: He collects their jewelry and fashions them an idol. Like the gentlemen at JPMorgan Chase, he understands that what’s truly at stake is not material but spiritual, and that what the people are asking for is assurance in a world that has none.

Moses, the wisest of leaders, knows all of this, and he refuses to succumb to the Lord’s wrath. Even God’s divine book, he knows, is written for humans, and no story is more human than striving to eliminate uncertainty. If the punishment for such human actions is genocide, he tells God, write me out of the book.

And God is soothed. He understands—neither for the first time in the Good Book nor for the last—that his people are stiff-necked, and that no matter how many signs they’re given, they’re still likely to abandon his ways for any fleeting chance at tangible, earthly representations of divinity. He realizes that the laws he advocates depend on faith, not evidence and are, therefore, an abstraction. And he knows that the people congregated in the desert, sweating and scared, vie for the concrete. Therefore, he forgives—he orders the Israelites to destroy their remaining jewelry, but he spares them their lives. There’s no other way to reconcile God and Man.

If he’s studying the Torah in his North Carolina jail cell, Bernie Madoff may take some comfort in this bit of divine good will. And let us, too, show Bernie some mercy: His crimes are terrible, but they transcend simple greed or sheer arrogance. As we learn from this week’s parasha, we’ve had Madoffs since the dawn of time, and we will continue to have them, most likely, for as long as we strive to impose order on a world that is unruly, for as long as we think we can fashion our own gods, for as long, that is, as we’re human.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.