Mapping the Temple

Daf Yomi: Talmudic rabbis, as distant from the original animal sacrifices as we are from the Civil War, try to piece together a layout that matches the Torah

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

The subject of Tractate Zevachim, whose fifth chapter Daf Yomi readers completed this week, is the exact ritual protocol for animal sacrifice in the Temple. The rabbis treat this subject with the same passion for exactitude that they bring to every area of Jewish law. They specify which sacrifices are offered in which part of the Temple courtyard, how the blood is sprinkled on the corners of the altar and poured out at the base, and when and where the meat from the slaughtered animal can be consumed. There are the usual disputes among the rabbis, but these have more to do with how a given ritual is derived from the Torah text than with the proper nature of the ritual itself.

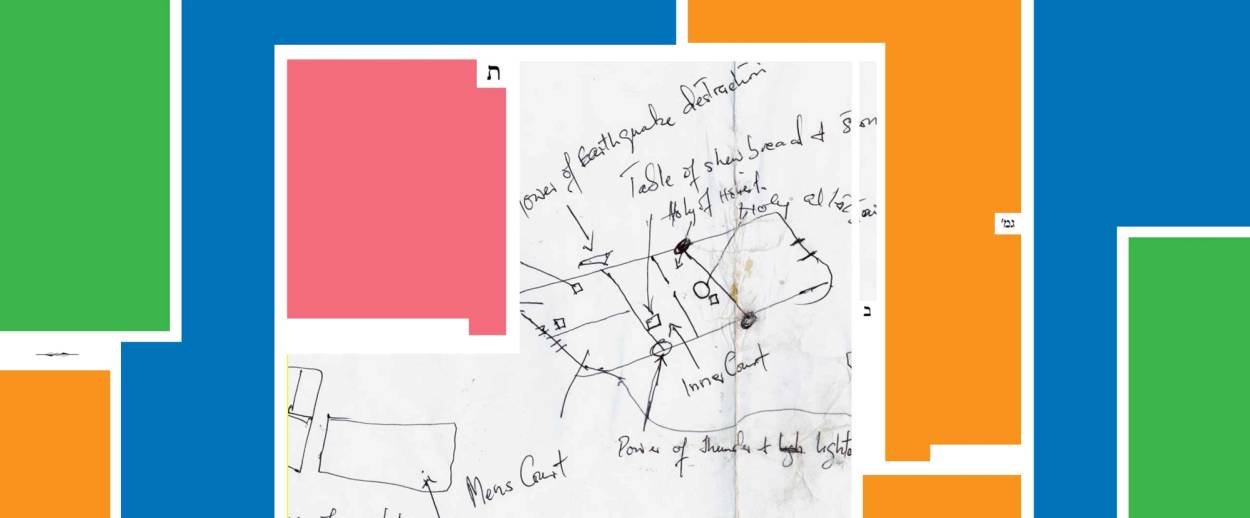

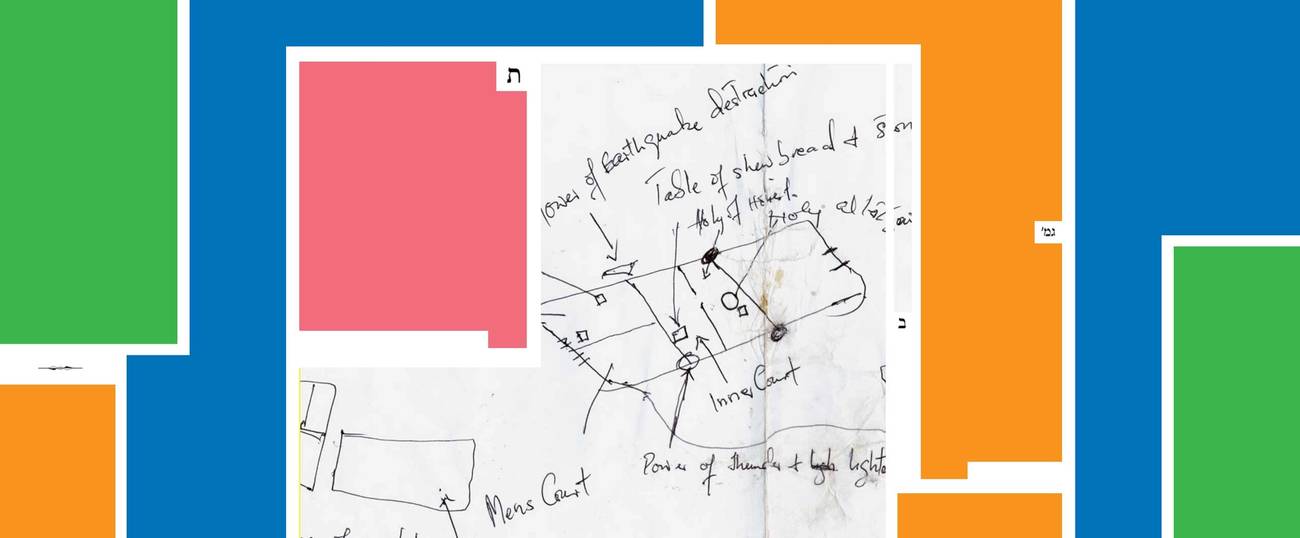

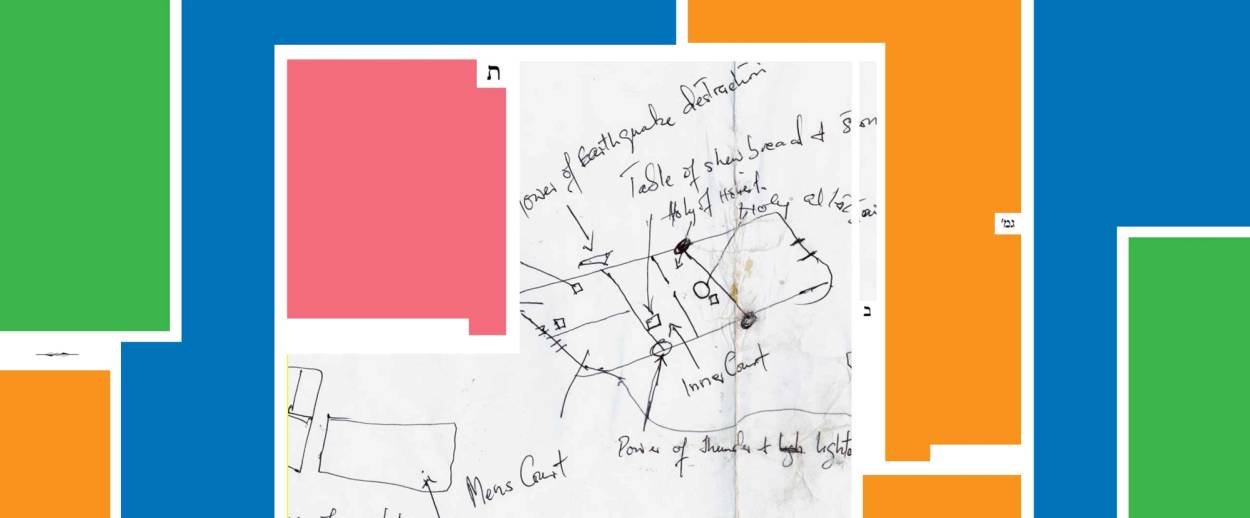

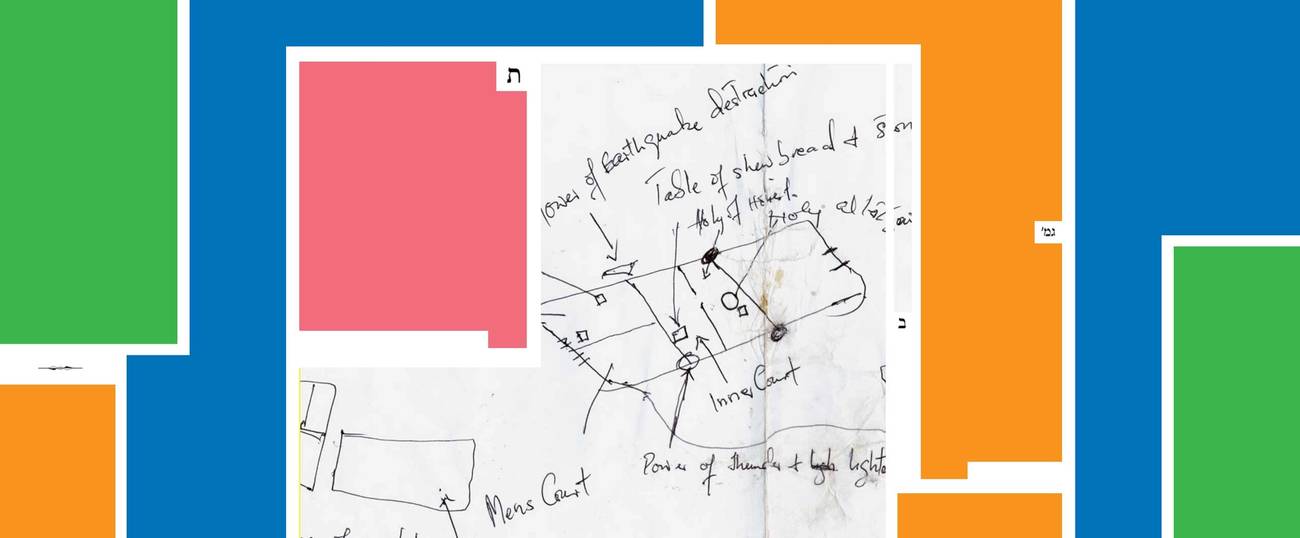

So it is strange to reflect that, by the time the Mishna was compiled around the year 200 C.E., no living person had witnessed a Temple sacrifice. Yehuda HaNasi was roughly as distant from the destruction of the Temple as we are from the American Civil War; and the amoraim, the rabbis of the Gemara, lived hundreds of years later. They were all trying to mentally reconstruct a series of long-vanished rituals that they knew about only from the Torah and from some scraps of oral tradition. Crucially, they had no diagrams, which would have helped enormously in figuring out the exact dimensions and placement of the altar, the courtyard, and the other parts of the Temple complex.

So it’s no wonder that they frequently ran into difficulties. Sacrifices were carried out on an altar, and involved two stages. First the blood of the animal would be sprinkled on the corners of the altar, each of which had a short post; then the remainder of the blood would be poured out against the base of the altar. However, the rabbis believe that the base did not extend all the way around the square altar; there was no base on the southeastern corner. This doesn’t seem to make much architectural sense, and it is not explicitly mentioned in the Torah. Why would the altar have been built this way?

The reason, the Gemara explains, is that the land on which the Temple sat was taken from the territory of two different tribes, Judah and Benjamin. According to Jacob’s deathbed blessing, Benjamin would have the privilege of seeing the altar built on his land. That is how the rabbis interpret the verse “Benjamin is a wolf that tears apart; in the morning he devours the prey, and in the evening he divides the spoil.” In context, this might seem to be a prophecy of Benjamin’s prowess in hunting and war-making. But the rabbis, who generally dislike such rough patriarchal activities, read the passage as referring to the altar, which is where the “prey” of sacrifices is “devoured” by the sacred fire.

It follows that the Temple altar has to stand on land belonging to the tribe of Benjamin. And since the southern and eastern borders of the altar stood on the land of the tribe of Judah, the altar did not extend into that territory even to the extent of the altar’s base. (According to Rabbi Hama, the Benjaminites were permanently jealous of the Judahites for even this tiny encroachment on the sacred space: “The tribe of Benjamin the righteous would agonize over it every day.”) Of course, the idea that a tribe’s territory could be accurately demarcated down to the level of inches—or, as the rabbis say, cubits—is highly unlikely. But the rabbis adopt the notion because it allows them to harmonize the Genesis tradition about Judah and Benjamin with the Leviticus tradition about the measurement of the altar.

Still, the idea that the altar lacked a southeastern base is inherently improbable, as the Gemara suggests when it cites a mishna: “The altar was 32 cubits by 32 cubits.” This suggests that it was a perfect square, with a base running along all four sides. Indeed, the Gemara in Zevachim 54a specifies that the altar was built by pouring a mixture of stone, plaster, lead, and tar into a wooden frame. How could this result in a base that was missing its southeastern corner? Perhaps, the Gemara proposes, the builder first makes a square and then cuts out the southern and eastern sides. But this would involve cutting the stone, and the Temple has to be built from uncut stones. Rav counters that the southeastern portion of the frame is not filled with the molten mixture at all; instead, the builder “places something under the frame,” such as wooden sticks, and then removes it when the altar has hardened, leaving an empty place.

But this creates a new problem. Several types of sacrifices require the priest to sprinkle the blood of the animal on all four sides of the altar. How can this be done if there is no base on the southern and eastern sides? The rabbis’ answer is that the base must actually extend one cubit onto the southern and eastern sides. The priest pours the blood on the northeastern corner and the southwestern corner, and the blood dripping down will flow a little onto each of the four sides of the square. (Shmuel asks us to visualize the Greek letter gamma, which looks like a right angle, with the southeastern corner empty.) In this way, only two sprinklings are required to place blood on all four sides of the altar.

Finally, the Gemara considers a seemingly fatal objection raised by another baraita, which specifically says that bird sacrifices were performed at the southeastern corner of the altar. (The procedure for killing a bird was up close and personal: The priest would pinch the nape of its neck with his fingernail.) If this corner had no base, how could the bird’s blood drip onto it, as the sacrifice required? “Is he merely performing the rite in the air?” asks the Gemara incredulously. But Rav Nachman ben Yitzchak has the answer: The airspace of the southeastern corner belongs to the territory of Benjamin, so a sacrifice performed in that airspace is valid. It is only the land that belongs to Judah, which is why the altar needs no base in that corner.

If the rabbis could have traveled back in time and visited the Temple, would they have found the altar just as they imagined it? Or would they have seen a regular square, complete with southeastern corner? I have a suspicion that it would be the latter, and that much of the rabbis’ ingenious theorizing is a result of a problem they themselves created. But of course, there’s no way to be sure—not until the Third Temple comes into being, as the rabbis were certain would happen someday.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.