‘We Must Engage the World Right Now’

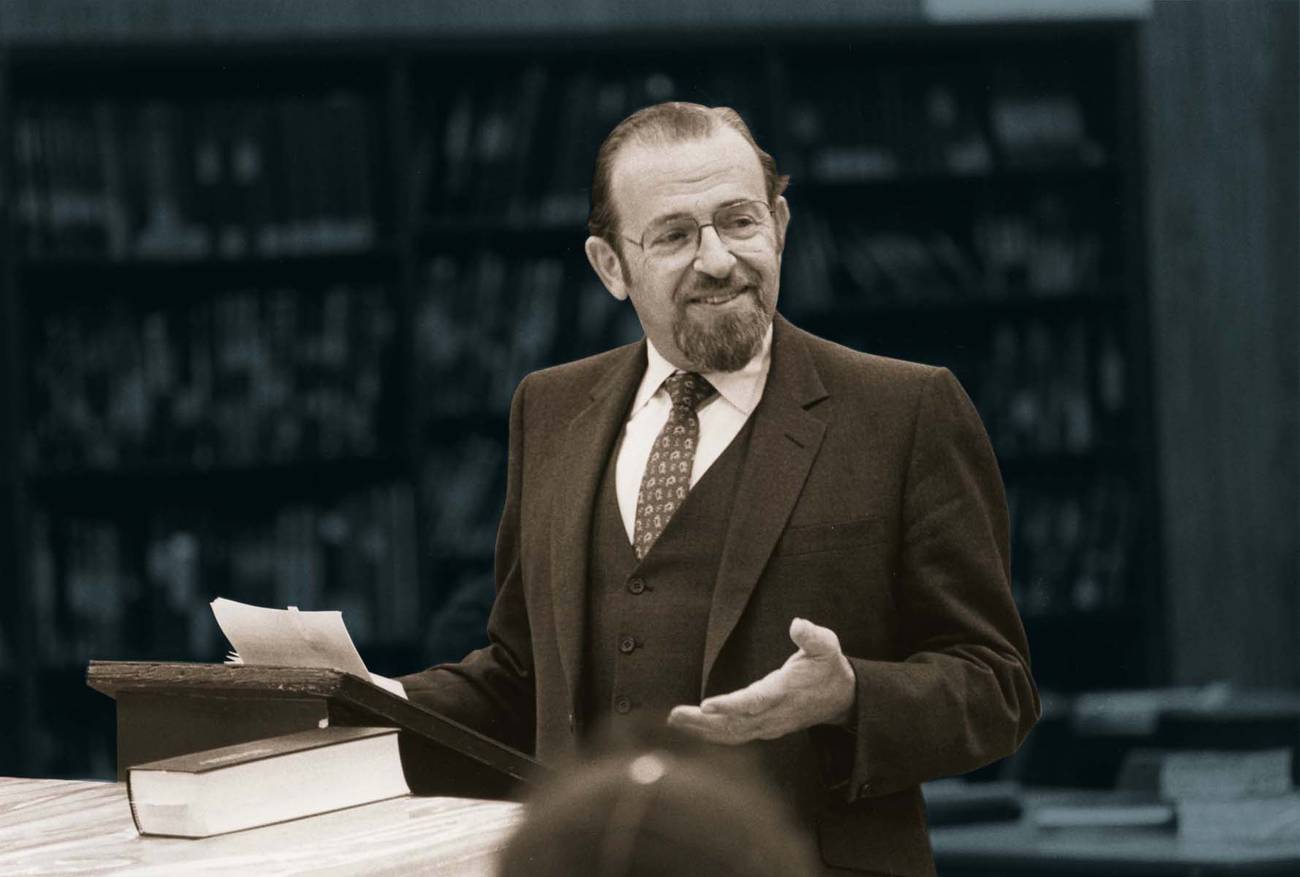

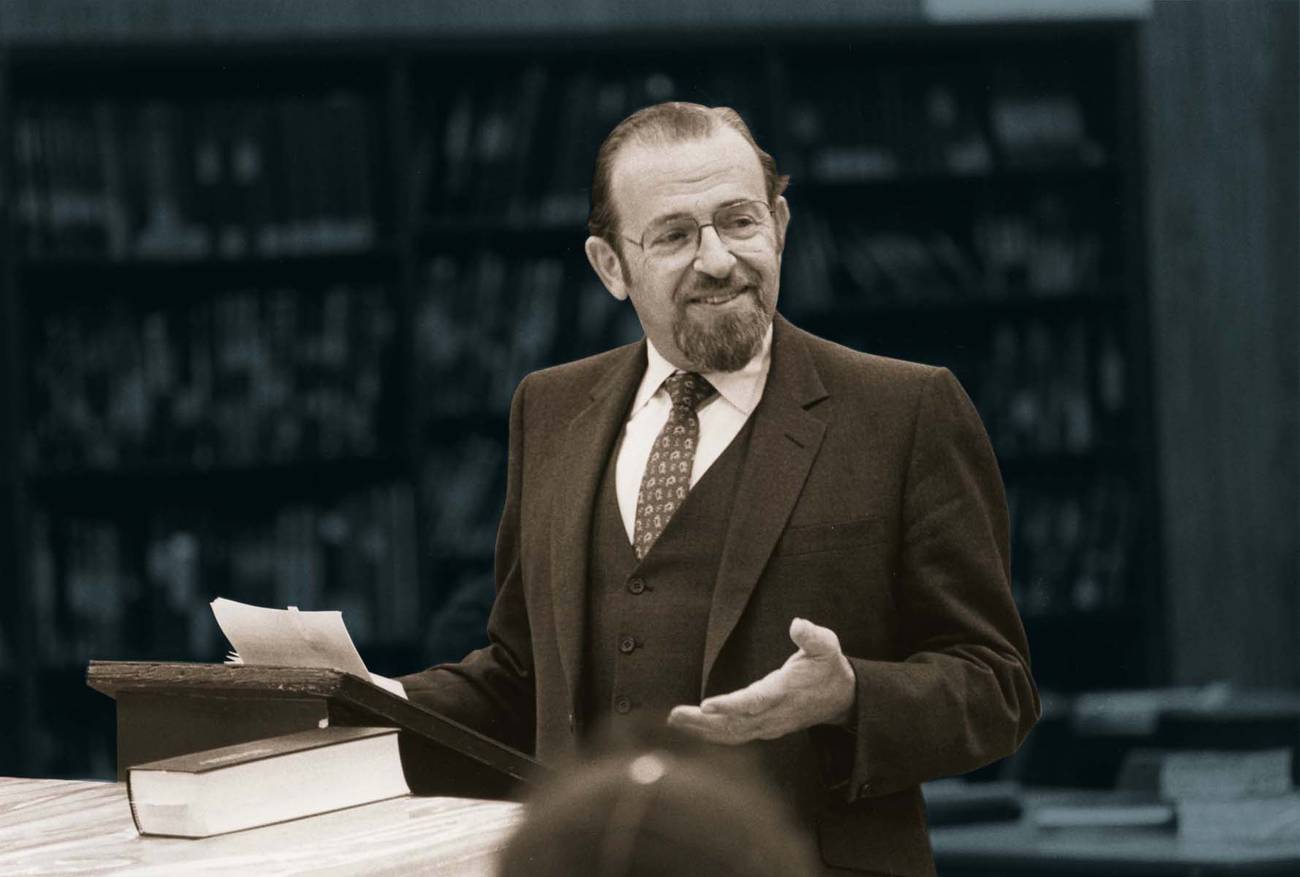

Rabbi Norman Lamm—theologian, orator, and my grandfather—believed that in the struggle against racism, Jews should both teach and listen

It was Sunday evening, the day after Shavuot, and my body felt like it was shutting down.

The first thing I learned when I turned on my phone just after the holiday ended was that my grandfather, Rabbi Dr. Norman Lamm, had taken a turn for the worse. By Sunday morning he had died. He was perhaps the greatest Jewish orator of the last century, legendary theologian, and president of Yeshiva University. He was also my guide, my hero, and my teacher. His death would’ve been devastating for me under any circumstance, but it was even more so because my beloved grandmother Mindella Lamm had passed away just a month earlier from COVID-19.

These twin losses, coming after months of sheltering in place and economic devastation and civil rights protests, were more than I could take. By the time I returned home from my grandfather’s funeral on Sunday, I felt something inside of me give out. I lay down on the couch. I couldn’t move. I could barely think. I slept. It didn’t help. The Jewish tradition warns us against despair, but, to be honest, at that moment I felt something very close to it.

In a daze, I stumbled to my bookshelf. I found my grandfather’s books, and began scanning through the tables of contents, searching for something, anything that would bring him back to me. I rifled through erudite disquisitions on religious doubt, Jewish higher education, modesty, even the spiritual implications of extraterrestrial life. All wonderful, but, somehow, I knew none of these would bring me what I sought.

And so I turned to his sermons.

While my grandfather’s many scholarly books and essays represented him at his most analytical, what I needed in my moment of anguish was not learned words on a page, but the sound of his voice. I needed to hear him speak from the soul. I needed his sermons, which, at their best, majestically captured the poetry of the Torah and its wisdom. I needed to see if he’d left behind any wisdom that might help me find some light in our dark collective moment. I clicked on the digitized database of his sermons, and clicked almost at random. And there, in a sermon from 1952, was the voice I was hoping to find:

“When the propaganda machines have ceased their loud clattering and the din of the partisan shouting has been silenced,” read the sermon, “the still small voice of religion must make known its moral and spiritual judgment.”

Consider the state of the Union when a young Rabbi Lamm wrote those words. The country was still mired in an increasingly unpopular overseas conflict. Domestically, a polio epidemic was sweeping across the nation. And on the social policy front, the nation was firmly in the bloody grip of Jim Crow. Twenty-seven states still had anti-miscegenation laws in force. Many states mandated racially separate services for railcars, to restaurants, to barbers. Three days after my grandfather preached these words, in fact, the Supreme Court began to hear arguments in Brown v. Board of Education.

I read and reread my grandfather’s words perhaps a dozen times. I was stunned. I could almost hear my grandfather calling out from the halls of heaven, reassuring the Jewish people and our country that there is a way forward; that the Torah—the still small voice of the Jewish tradition—must inform our present, and holds the key to our future.

For my grandfather, Torah required two things: listening and teaching. Regarding the first, my grandfather believed, with ancient Jewish tradition, that God is the architect of creation, and that the Torah is the blueprint from which He worked. So in order to know God and His Torah, we must investigate and appreciate all the mysteries of creation, from physics and astronomy, to literature, history and all other records of the human condition. My grandfather articulated this point as a fleshed-out philosophy in his most famous book, Torah Umadda, published in 1990. But its roots lie already in his sermons, which are replete with references not only to traditional Jewish sources, but also the writings of Plato and Aristotle, scientific and literary journals, and great works of contemporary philosophy and social critique. The point is clear: In its most refined form, Judaism requires that we listen to, and learn from, others.

This is a critical message for us in 2020: As the nation continues to wrestle with historic mistreatment of black Americans, now is precisely the time when listening to those communities tell their stories would be both a source of increased wisdom and a catalyst for healing. Keeping our ears open to black experiences can help us better understand our fellow bearers of the divine image, and bring to life the Torah’s call, enshrined on the Liberty Bell, to “proclaim liberty throughout the land.”

A willingness to listen is especially important at a time when prominent voices in the commentariat and government close their ears in the name of “law and order.” In a sermon delivered in 1968, following unrest in nearly every major American city in the wake of Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, titled “Law and Order,” Rabbi Lamm preached:

Human law is important—but it is not infallible, inviolate, or absolute. It must be subordinated to a divine dayyan [judge]. In essence this means that law prevails, but not above conscience, not above religious principle, not in the presence of a higher moral code. Therefore, for instance, Jewish religion teaches that dina de’malkhuta dina, that the law of the country wherein we dwell remains our law. However, when such governmental law bids us violate the law of the Torah, then it must yield, for human law is subordinate to divine law.

The higher, divine law requires us to listen and learn so that, as the Psalmist taught, we may gain a heart of wisdom.

But listening alone is insufficient. In fact, it is cowardly, reflecting a belief that deep down we have nothing to add ourselves. The student of Torah has much to learn from others, but has tenfold as much to teach. As my grandfather relentlessly emphasized for decades, all of society—the lofty and downtrodden alike—desperately needs the Torah’s wisdom as well.

If that strikes you as a rabbi’s wishful thinking, take a moment and study the long and still ongoing struggle for freedom and rights in this country. In the entire history of our nation, we have not achieved a single victory in the fight against racism that hasn’t depended upon the values and stories of the Hebrew Bible. Abraham Lincoln, perhaps America’s foremost theologian of liberty, drew extensively upon the Hebrew biblical tradition, especially in his famous Second Inaugural Address. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography of Frederick Douglass, David Blight referred to the legendary black orator as a “prophet of freedom,” noting “Douglass’ deep grounding in the Bible, especially the Old Testament.” Martin Luther King Jr.’s public addresses are saturated through and through with learned references to the great Hebrew prophets, from Isaiah and Ezekiel, to Amos and Zechariah. Barack Obama’s repeated references during the 2008 presidential campaign to “the Joshua generation” are incomprehensible without an understanding of the Hebrew scriptures. It is true, as Haifa University’s Eran Shalev documents, that white abolitionists in America’s antebellum period evinced an increasing tendency to invoke the Christian Bible as well. But this “further spotlights the one group that did not take the privileged American majority’s lead in preferring the New Testament to the Old: black Americans, enslaved and free, would remain committed to the Hebrew Bible throughout the antebellum period and beyond.”

The Torah, as my grandfather understood, is civilization’s best hope. It represents the greatest, grandest moral tradition in the history of humanity. America’s Jewish and black communities (which, of course, sometimes overlap), have always understood this best. And without the Torah, my grandfather warned during the turbulent summer of 1953, we all become “easy prey for any cruel ‘ism’, which can tyrannize the empty souls of ignorant children, from atheism to communism to materialism.”

This is my grandfather’s answer from beyond the grave to the question of how Jews should contribute to society. Should we attend rallies? Should we give to activist causes? Should we call our members of Congress? Perhaps all of the above are worthy options. But these are activities in which anyone can engage. But what can we do that no one else can? What unique service can Jews render to society?

My grandfather’s answer is that we are the ones best prepared to bring forth the Torah from Zion and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem. In my grandfather’s words, “we must engage the world right now and, speaking in a cultural idiom it understands, say that we are dissatisfied with it.” The answers society seeks will not be found in secular academia, the jargonized world of activism, or the trendy domains of pious social media exhibitionism. None of today’s cruel, or even just empty “isms” could ever substitute for the majesty and wisdom of the Torah.

To give just one example: In place of the clunky, alienating phrase “systemic racism,” we can instead teach an American public still attuned to the language and morals of biblical religion that racism constitutes the sin of idolatry. Rabbi Lamm, in fact, developed this theory in several sermons spanning almost a decade. The Shabbat after the march on Washington in 1963, my grandfather drew upon the 19th-century commentator Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin (known by the acronym “Netziv”) in explaining that idolatry—a crime that usually requires the support of an entire social and cultural apparatus—is the best way to think about racism in America:

It was bad enough when hate-frenzied mobs lynched individual Negroes, but this crime of shefikhat damim [homicide] is exceeded by the greater blot on our record: the methodical economic exploitation of one segment of our population, the systematic oppression of one race as the source of cheap labor and its designation as the first to suffer in any economic recession. When the economy of a great nation is built upon such patent injustice, it is a crime of avodah zarah [idolatry], it is a breach of faith. It bespeaks lack of faith in G-d who is av echad le-kulanu, One Father for all humans, making us all brothers.

Here we can find all the concepts that talking about systemic racism hopes to convey. But rather than reflecting the sterile terminology of academia’s secular gospel, Rabbi Lamm drew from an elevating biblical vocabulary that has always nourished this country. He employed the only common language Americans have ever shared for discussing race, equality and human dignity: the Hebrew Bible. These, my grandfather reminds us, are the truths we can and must teach our fellow Americans.

My grandfather believed that the Jewish people must listen to and learn from others, yes, but he also knew that we must never accept the role of listening or following only, even when this is what social justice activists demand. This would be an abdication of our responsibility to teach, bringing the Torah’s insights to those around us.

Reading through my grandfather’s sermons, the dual charge to listen and to teach, came through clear as day. But the more deeply I delved into them, the more I also began to perceive a warning simmering just beneath the surface. I think he expressed it best in a sermon from 1970, “Confessions of a Confused Rabbi,” delivered two weeks after the Kent State shootings and shortly after the beginning of America’s Cambodian campaign.

In that sermon, my grandfather relates that young people in his congregation had approached him to ask why he hadn’t addressed those events when they occurred. He confessed that he felt conflicted. On the one hand, he was outspoken against the Vietnam War and considered the Kent State and Jackson shootings “a blot on the history of our nation.” Moreover, he several times delivered spirited (if qualified) defenses of hippie culture and ’60s campus activism. (Considering his audience of prim, refined German Jews, that was probably the bravest stand he ever took in his rabbinic career). And yet, as he explained, he could not go all the way with the zealous student activists of the day. He gave several reasons, but the third one in particular stands out:

Third, I question the priorities and consistency of many Jewish students when they make of the Black Panthers a cause celebre of their moralistic movement. Yes, I agree that they are, in this country, entitled to a fair trial and to be protected from police brutality and vindictiveness. I believe we should see to it that the police who were brutal are punished, and that even Black Panthers receive their rights as American citizens. But they are not our friends! They are anti-Semites and they are anti-Israel. I would like to see young Jews who seek justice for the Black Panthers—and more power to them in their passion for justice—oppose these pernicious anti-Semites with equal zeal.

Although my grandfather considered the anti-racist cause for which the Black Panthers, the most influential black militant political organization of the late 1960s, fought a righteous one, he could not and would not ignore their blatant anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism. Citing the early rabbinic sage Hillel’s famous dictum, “if I am not for myself, who will be?” he exclaimed, “I have nothing but contempt for the so-called ‘universal’ Jew who makes every people’s concern his own, save that of his own people.”

That my grandfather believed with all his heart that black lives matter and, in light of American history, require special care and protection, I have no doubt. He said as much, and more, over the course of decades’ worth of preaching and teaching. What, however, would my grandfather have thought of the Movement for Black Lives, an umbrella organization that, to this day, proudly proclaims on its website that Israel is an apartheid state (in its “Cut Military Expenditures Brief”)? We cannot know of course. What I do know is that he insisted that everything we do, we do not because we are “allies,” but because we are Jews. That means that we are morally bound—whether by God, as he believed, or at least by the force of history or self-respect—to exhibit no tolerance for those who would demonize our people. As my grandfather stressed, “we have no right merely to dismiss offhand the interests of kelal yisrael [the Jewish people].”

I suspect that while today’s Jewish community’s anti-racist activism would have made him proud, as it did once upon a time, he would have been horrified by those, like the Movement for Black Lives, who ignore, excuse, or only half-heartedly protest the defamation of our people by those who should know better. It would certainly be much easier, especially in the untamed wilds of social media, to downplay our concerns, or weakly deflect that “this is not about us.” But as my grandfather preached in that same sermon from 1952 with which I began, “if Peace conflicts with Truth, Peace must go and Truth must prevail.”

By the time I finished reading, it was long past midnight. I had read through dozens, maybe hundreds of sermons, luxuriating in the sound of my grandfather’s poetic, prophetic voice. Yes, I was still completely heartbroken. But I found that I could stand a little straighter. In a world and at a time that feels so broken, I began to feel a surge of hope. My grandfather may have departed this world for the next, but he left his wisdom behind for us. He instructed us to listen with an open heart to the perspectives of others; he charged us to bring the Torah out into the world around us; and he cautioned us never to forget our Jewish self-respect when we engage with society.

In the end, as I eventually drifted off to sleep, all I could think about were the words with which my grandfather concluded his eulogy for his own grandfather in 1949: “I [imagined] him say to me, in an affectionately mocking tone, ‘Why make a fool of yourself crying here now?’ And then, ‘Go home and start learning. You have a lot of constructive work to do that you’ll be missing if you tarry here too long. Not that I mind your presence …’”

Rabbi Dr. Ari Lamm is the CEO of the Bnai Zion Foundation, and a historian of religion