Passover’s Perennial No-Show

At the Seder, we open the door for Elijah. As a child, I thought he’d actually appear. Then I grew up, and anticipation faded into resignation.

I was only 17, but suddenly I felt old.

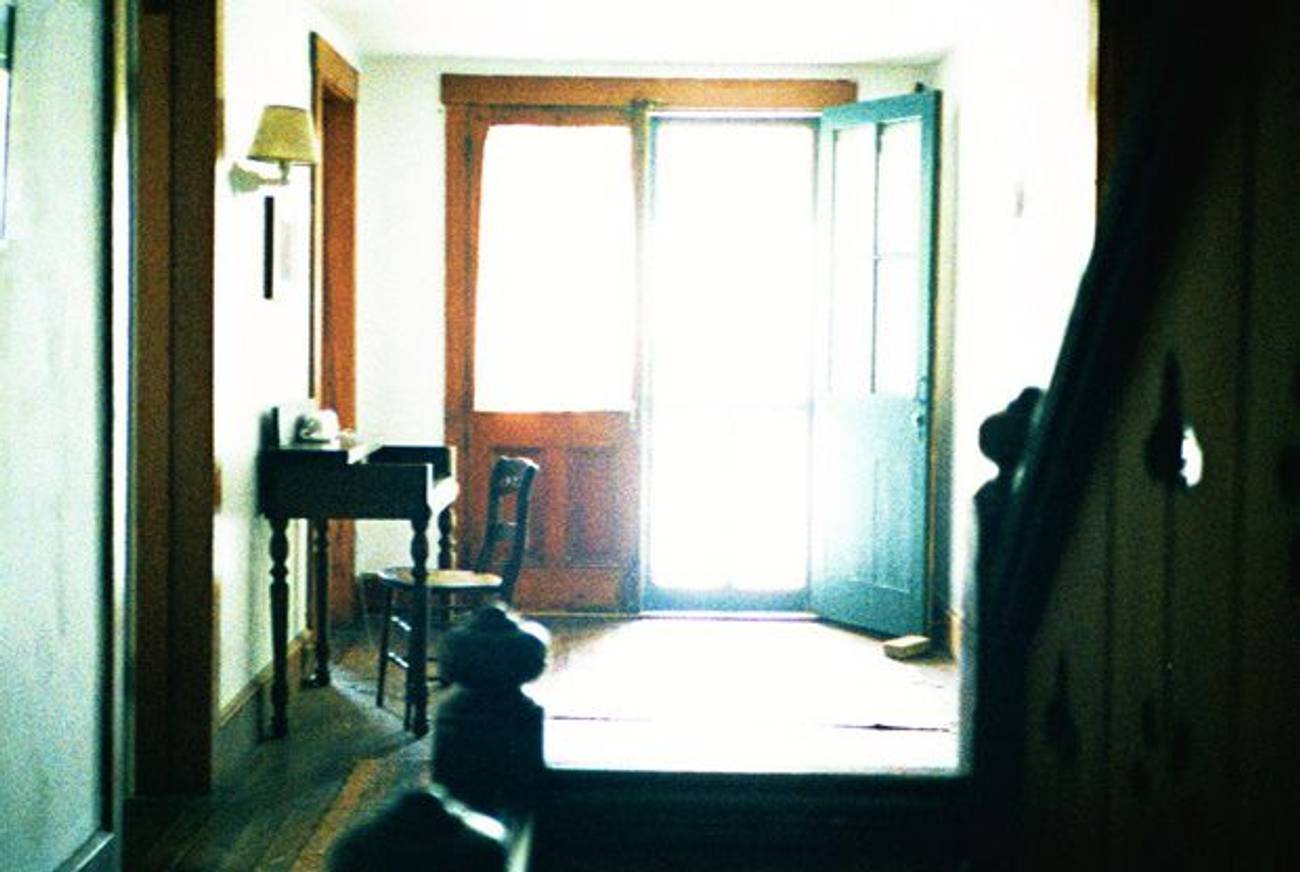

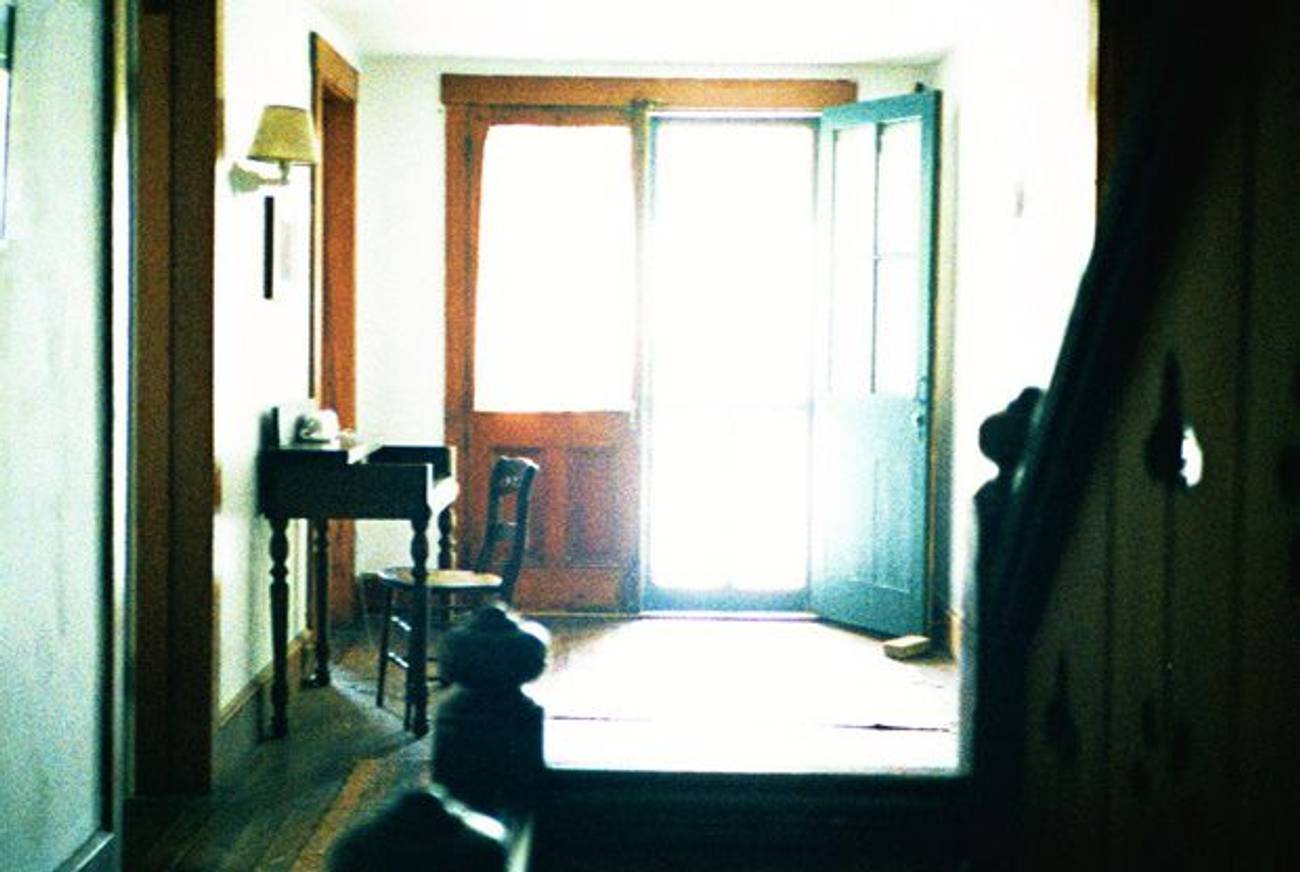

It was the night of the Seder, three years ago. I stood by a wide-open door, a door that had not been knocked on, by a threshold that was unmistakably empty, and wondered whether the person I’d hoped—maybe even expected—to appear had been a figment of my imagination, a fading piece of the naïve child I had been.

The weeks before Passover that year had found the Orthodox Jewish world buzzing, more than usual, with talk of the Messiah. The Iranian nuclear threat, the growing anti-Semitism worldwide, Israel being torn to pieces by the media—It only leads to one conclusion, the old men in synagogue exclaimed and the schoolgirls whispered. We are now experiencing the birth pangs of the Messianic era. Any day now, he’ll come on a magnificent white horse. Students were told to do more good deeds, to give more charity, to refrain from slander. We women were encouraged to learn more Torah, wear longer skirts, pray more; according to the Sages, after all, it is in righteous women’s merit that the Messiah will come.

Even Brighton Beach’s expatriates from Odessa and Kiev had heard of the rumors.

My Ukrainian-born grandmother had called several days before the holiday: “You know what I just heard a rabbi say on the Russian radio? According to the Jewish calendar, this year the sun lines up in the same position as it had during Creation. This happens only once in 28 years!”

“It’s the year of birkat hakhama,” I said. The vernal equinox, the completion of the solar cycle according to Talmudic literature.

“But this year’s position is the same one as the year of the actual Exodus from Egypt,” said my secular grandmother. “It has all these energies. Of freedom, miracles, you know?”

Even my Soviet-educated relatives, the ones who’d pile into small Toyotas and drive in from Brooklyn to join us on Seder nights in New Jersey, were wondering about what might happen on Passover. The Russian rationalists were careful to check the family passports’ expiration dates. Who knows? Maybe Elijah the Prophet will come this year and will take us to Jerusalem; it would be a shame if our papers were out of order.

My younger sisters, too, were making plans for the impending Redemption and checking Israeli real-estate websites for pretty villas. Mili, then 7 years old, announced that she was keeping a packed bag under her bed, in anticipation of a sudden journey to Jerusalem. I had laughed and patted her shoulder.

Yet despite my laughing, I, too, found myself anticipating. I’d lie in bed, look at my posters of the Galilee and the Mediterranean, and wonder how it was that I could be such a worldly 17-year-old, a reader of Chekhov and student of calculus, and still, secretly, fervently, believe in a Messiah. How was it, I wondered, that I found myself setting an extra seat for Elijah, just in case he needed to sit down and eat some of my mother’s chicken de provence before continuing to the next house?

I was sure that his arrival was imminent. Even when, during the first Seder that year, my father rose from the table to open the door for Elijah and ask God to redeem us, to pour out His wrath upon the nations that know Him not, upon the kingdoms that did not call upon His name, for having consumed Jacob and for having laid waste his habitation, and for Petliura’s crusades and Stalin’s purges, for Babi Yar and for that Iron Curtain, too. All of history raining down on us, until we’re forced to throw our doors open and demand justice. Pour out Thy rage upon them, let Thy fury overtake them.

But I sat in dread, because suddenly I realized that there was no justice. The other side of the door would be empty, as it always is, only a slight mocking breeze, a wet street with street lamps in pools of yellow light.

We stood at the table quietly as Papa recited the prayer by the empty doorway.

As a child, I thought that the longer that Papa lingered by the door, the greater the chances that it would happen: that Elijah would come running up our front path, panting and out of breath, his embroidered robes flying. Wait, wait, Doctor Dovid, son of Leib! I’m late, the neighbors held me up! And each year that would pass without Elijah’s arrival, I learned to nod and insist that he’d undoubtedly come next year.

According to our tradition, Elijah’s wine glass would be left out overnight on the kitchen counter, in case he decided to show up later. Growing up, I used to jump out of bed on Passover mornings and check the glass and, when noting that the wine level had dropped by a hundredth of a millimeter, conclude that Elijah had indeed stopped by and taken a sip.

But that night, facing that open door and that invitation that once again went unheeded, I stopped expecting Elijah; he became the friend that always canceled last-minute. I understood that he wouldn’t come during the Haggadah reading, not when we opened the door for him, not while we slept. Not even on a night when the sun’s position was in the exact same place as it had been during the Exodus.

My father’s walk back to the table from the front door was slow, steady. “Well, let’s proceed,” Papa said, looking to my mother and turning a page in the Haggadah. But our disappointment in God and in peace and in destiny didn’t have time to settle—the younger kids had finished preparing their annual Passover performance.

They came trumpeting down the stairs, holding boxes of stage props, shouting for the grown-ups to be quiet already—they were just about to start their Pesach show. Years before, as the eldest, I had been the director of the holiday performances at family gatherings; I’d write the script several days in advance, boss the younger kids around, and scold them for not remembering their lines. Now I sat and smiled demurely at the adults’ table, but it felt like yesterday that I had stood there, too, in biblical robes, stepping carefully through an imaginary Red Sea into a Promised Land.

The adults laughed as my cousins and sisters performed their antics. Here were Moses and Pharaoh, in clothing made of bed sheets, badminton rackets serving as shepherds’ staffs. Two blue blankets were the Red Sea; the smallest cousins walked between them into freedom. And then, the conclusion, a look to the future: My youngest sister came out, riding a toy horse and wearing a long white beard—the Messiah.

We clapped and cheered on the little theater troupe. What a clever performance! And then we finished the Seder. I smiled weakly and sang the conclusion in Hebrew, the same words Jews have been singing for thousands of years: Next year in Jerusalem. I realized, with discomfort, that I was tired of it.

“Such a lovely phrase,” my great-aunt remarked. Yes, lovely. These enlightened Kiev-born engineers and Kharkov-born teachers, physicists and doctors, were now sitting at a Seder table in New Jersey, yearning for a bearded Messiah to come. They were suddenly somber when they remembered Jerusalem and her white limestone alleys. As I looked around, I noticed that there was something heartrending in their faces.

At 17, that Seder night, I went through the Diaspora Jew’s rite of passage. I silently understood the duality of anticipation and resignation; how to whisper breathily about the promise of peace, while glancing back at Jewish history, amused with my own naïveté. I learned to say “Jerusalem” with a millennia-old sigh and faraway eyes, just as my ancestors had always done. And when the relatives sat and drank tea, talked and laughed—not about Elijah or the future, but perhaps about politics and history and anecdotes, as they had always done, I learned to join them, behind a door left only slightly ajar.

Avital Chizhik is a writer living in New York City and a frequent contributor to Haaretz.