Republic of Letters

This week’s parasha argues that to become a great leader one must see beyond earthly concerns. It’s a lesson Israel’s current leadership could stand to revisit.

Herein is a newly revealed protocol from a meeting between some of the Israeli government’s highest-ranking officials, dated Jan. 21, 1958.

“Instead of Dewey,” said the professor, “I suggest Whitehead.”

The historian was distracted. He turned to the old man. “Do you want to translate all of Pliny?”

“We need to translate all of it,” the old man said. “It’s a book from the time of the Second Temple, and it played an important part.”

The professor seemed incredulous. “Did you enjoy all of Pliny’s answers?” he asked.

“I did not enjoy them,” said the old man. “I was disappointed. But he’s the only one we have left from the time of Flavius. It was an entire Jewish world.”

A few more asides were tossed around. Then the gentlemen continued to talk about Pliny. The poet said he agreed with the old man: The Roman philosopher was worthy of consideration. “But it’s not easy to digest all of his work,” he added. “Also, I’m missing Maimonides. Without Maimonides I can’t consider myself educated.” And so it went for hours.

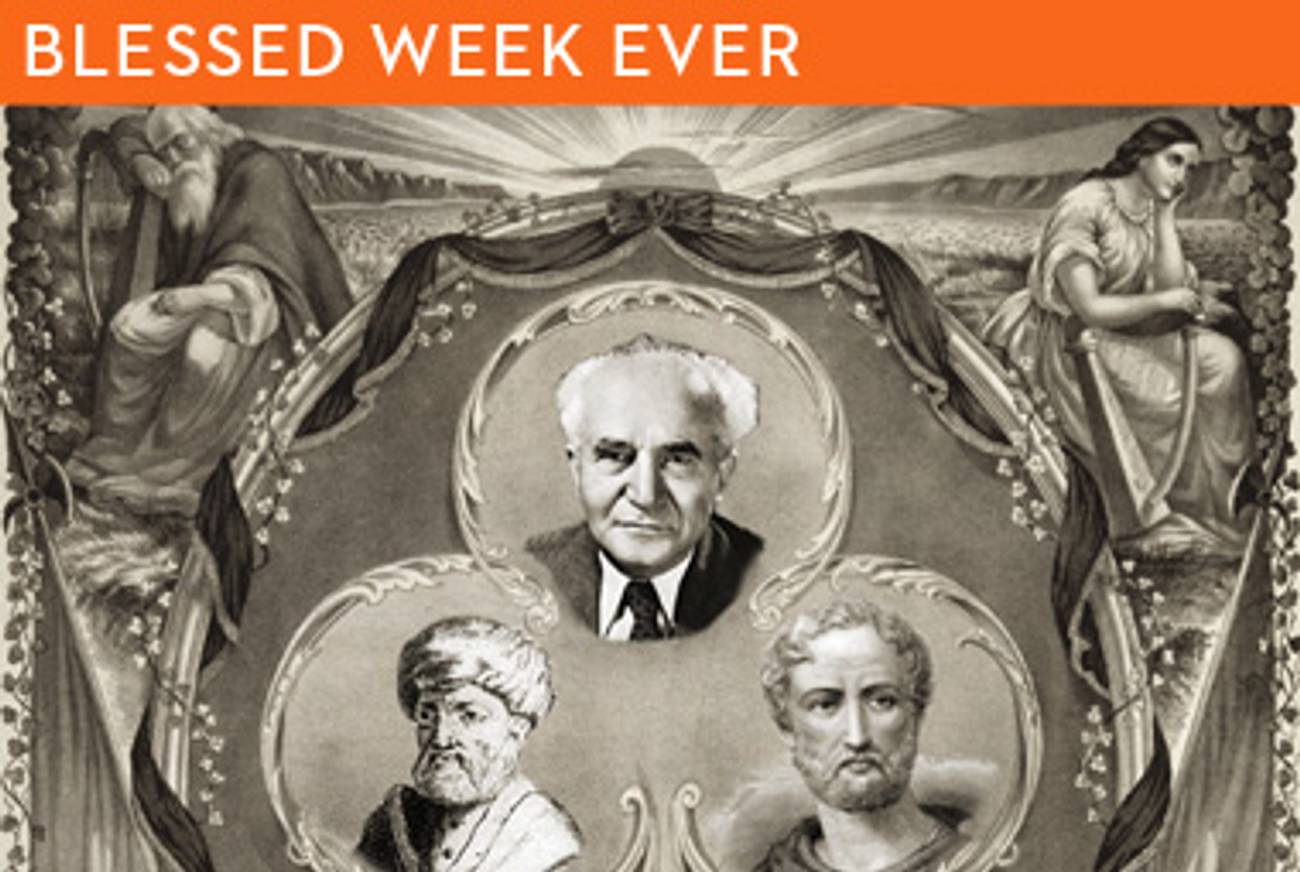

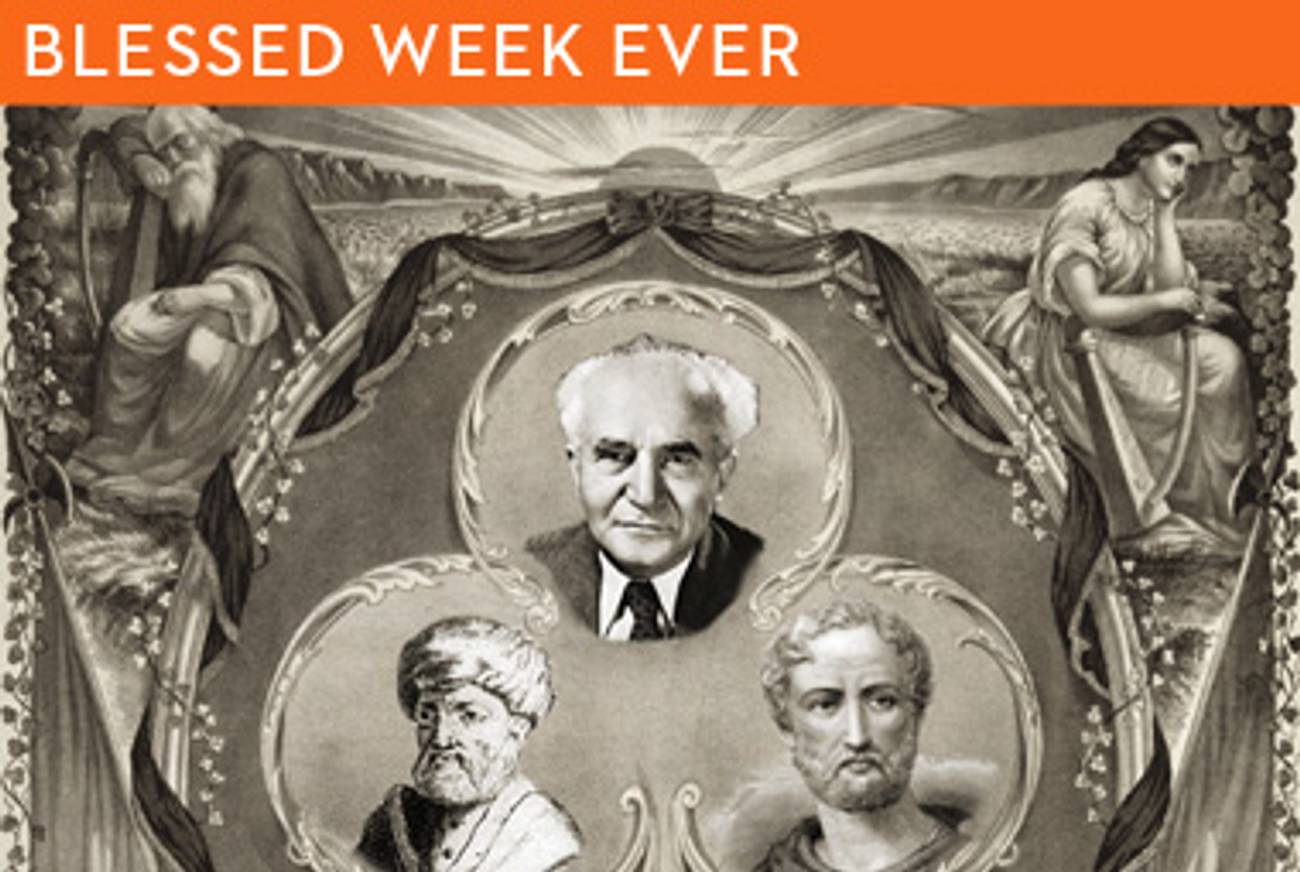

The discussion did not take place in a musty office at some university. Nor was it held at an obscure salon, or among aging intellectuals. The old man was David Ben Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister; the professor was Martin Buber, the historian Ben-Zion Dinur and the poet was Zalman Shazar, who a few years later would become Israel’s third president. They were gathered—along with other intellectuals and politicians—in the prime minister’s office, discussing what they all deemed a matter of great national importance: a government initiative to sponsor the translation of key classical works into Hebrew.

“You may think I’m a dreamer,” said Ben Gurion, channeling his inner John Lennon, “but the idea has been nagging at me for many years. Ever since the founding of the state I’ve felt that alongside founding a state we must also found a republic of the spirit. … We must provide our generation, in Hebrew, with all of the treasures of the human spirit, as each and every one of us is also a citizen of the world.”

Reading the meeting’s protocol this week, I was touched. Here, after all, was Israel’s founding father, fighting not only for the Jewish state’s physical survival but also for its intellectual well being, as comfortable talking about the Upanishads (he liked the overall vibe, but found the abundance of minor details too cumbersome) as he was discussing U.N. resolutions. Here was the architect of modern Jewish nationhood acknowledging that even in the midst of struggling for a homeland, one must never abandon the affinities that bind one to humanity at large and that span across time and cultures. Hallelujah, I thought, and amen.

And then I read the news. Ben Gurion met with Buber; Bibi Netanyahu, his eventual successor as Israel’s leader, couldn’t even meet with Justin Bieber. Ben Gurion’s government approved funding for a translation of Ibn Khaldun, the great 14th-century Arab historian; Netanyahu’s Cabinet helped pass a bill to defund institutions that teach the Arab point of view on Israel’s establishment.

These are more than mere differences in style. Regardless of political inclinations and ideological convictions, watching Netanyahu at the helm is a painful lesson in the corruption of a formerly great institution—Jewish leadership—which has historically perceived its duties as being simultaneously sacred and concrete, in charge of navigating earthly affairs but constantly fixing its gaze upon the heavens.

It’s an ancient tradition, and it is also the focus of this week’s parasha, which deals largely with the kohanim, or priests. These servants of God, we’re told, cannot come in contact with dead bodies or marry divorced or promiscuous women or serve if they are in any way physically deformed. From a modern perspective, the letter of the law is harsh, but its spirit is profoundly moving: When it comes to leading the people, we must demand no less than severe purity.

One could object, of course, and argue that the priests weren’t truly the leaders of the nation but merely its clerics, a small and separate and holy caste. But much evidence suggests otherwise; when God identifies the Israelites as his chosen people, for example, he commands them to be “a kingdom of priests, and a holy nation.” The recurring dichotomies between the worldly and the divine are not incidental. The children of Israel must become not just a kingdom, but a kingdom of priests, not just a nation, but a holy one. Their notion of leadership, therefore, must revolve not only around canny politics and able armies, but also—and primarily—around the spiritual essence through which the Lord had set them apart from the rest of mankind.

A similar discussion is held later on in the biblical story, when the Israelites demand to be governed by a king. The prophet Samuel, the nation’s shepherd at the time, is appalled, but God soothes him. “Listen to all that the people are saying to you,” he instructs Samuel. “It is not you they have rejected, but they have rejected me as their king. As they have done from the day I brought them up out of Egypt until this day, forsaking me and serving other gods, so they are doing to you. Now listen to them; but warn them solemnly and let them know what the king who will reign over them will do.”

In the eyes of God, a king is a distraction from the grand vision of Sinai, a vision that imagines the entirety of the populace as holy, the whole nation as priests. But if a king must be appointed, let the people beware, and let the king himself govern only by the grace of God. It is not surprising, therefore, that the bulk of the Bible is dedicated to tales of mighty rulers felled by the Lord after losing their piety: In Israel, being in charge means being holy.

This is a much more momentous task for a contemporary leader to undertake. The exacting rituals described in this week’s parasha and elsewhere no longer apply. But the principle still stands: Every Jewish state must, at least in part, be also a republic of the spirit. Ben Gurion realized this instinctively and worked to disseminate great works of literature and philosophy. It is time for the same spirit to once again stir in the prime minister’s office in Jerusalem.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.