Saying #Kaddish

As an atheist, I needed to find my own way to observe Jewish rituals when my father died

For most of my life, a vexing question had gently gnawed at me: What would I do when the dreaded but inevitable day arrived that one of my parents died? Specifically, what would I—an atheist—do about the Kaddish? When the answer came, the day after my father’s funeral, it was as unexpected as it was spontaneous. And it came with a hashtag.

Mine had been a typical South African Jewish upbringing. I grew up in Durban, a semitropical, semicolonial, semisleepy city on the Indian Ocean. The pedestrian intrigues of community life, the political situation, and—always—the beach were the stuff of our daily preoccupations. My dad, Lenny to all, was an orthopedic surgeon, meaning he had transportable skills. In June 1976, there was an eruption of violence in Soweto, 400 miles away. Black children, protesting the use of Afrikaans as the language of instruction in their schools, were gunned down in the streets by the feared boere, the South African police. My mother told me about it in grave tones when she picked me up from school that day. “Race riots.” I had never heard the term. Within days the country was engulfed in violence. A few months later, in December, we decamped to Cape Town for our summer vacation. As we lay on the exquisite, whites-only beach, smoke from ongoing “unrest” in the African and “colored” townships and shanties inland drifted over majestic Table Mountain. It was clear that our own “fight or flight” moment was upon us.

We immigrated to America in 1978; I had just turned 16.

In South Africa, my Jewish education had been rigorous, if not quite to a yeshiva standard. My younger brother Anton and I attended Carmel, the Jewish day school in Durban. Ours was a largely Orthodox community; many of my classmates were ostentatiously religious, vying to outdo one another in their displays of religiosity, with flamboyantly embroidered yarmulkes and extravagant swaying and wailing during our daily morning prayers. The rest of us, gently secular, endured the relentless blasts of Jewish studies and Hebrew classes with irreverent humor; we did our best to resist the powerful undertow exerted by the community elders, with their residual memories of the “old country” and its shtetls, and their fear of being the generation that would let its guard down and allow us all to assimilate. We went to shul every Friday night (which didn’t necessarily mean that we attended the services). The boys laid tefillin at school every morning (we called it “Jewish bondage”). I could recite the Amidah by heart (at least until the interminable silent bit). I still can.

I was culturally Jewish, an identity I enthusiastically embraced. Growing up in a Jewish home—my kashrut-observant grandparents were pretty frum, my parents less so, although they still avoided pork and shellfish—I observed religious rituals. I sang the songs and offered bikkurim (a shoebox filled with fruit) on Shavuot. I loved the Passover Seder. I fasted on Yom Kippur and walked to shul (many miles) and even put stones in my shoes so that the walk wouldn’t be too easy or too comfortable. (A family of menacing brothers, certainly the most fanatical of the religious clans at our school, told the rest of us to do that. Who were we to challenge them?)

But even as I observed these rituals, I can’t think of a single moment when I believed in God in any form, much less the form prescribed by my own religion. So when, eventually, I learned the word “atheist,” it was a “phew, so that’s what I am” kind of moment. I was 14; the tedium of studying for my bar mitzvah, pantomiming the behaviors of a good Jewish South African boy, lay behind me. And when we emigrated two years later, my years of religious instruction were formally over. Sure, we’d go to shul in Larchmont most Friday nights and my siblings and I were dragged to the High Holidays, but my mom never went, and my dad was clearly just following some expected script.

School in America was a revelation. There were (of course) lots of Jews in Scarsdale, but the alternative school I opted to attend was joyously secular and screamingly liberal. Rashi and Martin Buber had no place there. Instead I was suffused with John Stuart Mill, Karl Marx, Thoreau, Faulkner, and Virginia Woolf. Religion, for me, became even more rigidly compartmentalized: When I was around family, I’d sing the songs and eat the prescribed foods. When with my friends, at the A-school and then later at college in upstate New York, I never gave it a thought.

I took a long time getting around to marriage, and when I did it was to a (not particularly religious) Presbyterian. She and her two daughters expressed incredulity at my ability to square my avowed atheism with my penchant for sometimes reciting the Kiddush over wine on Friday nights, trying to fast every Yom Kippur, and enjoying the Seder. How could I possibly do all of those things yet plausibly claim not to believe in God?

Ritual, I feebly retorted. Isn’t that the point of ritual? To not be thinking too deeply about the meaning, while going through the rote motions?

The thing that most of the rituals I chose to observe had in common was that they were relatively easy to adhere to, self-contained, and involved food and community. Kiddush over wine? Thirty seconds on a Friday night before dinner. The Seder? Who doesn’t love a Seder, especially with the little kids mah-nishtana-ing, the dayenus and ilu-hotsianu? Even Yom Kippur: an indulgent flirtation with self-denial once a year, followed by cinnamon buns and many varieties of pickled herring (a South African Jewish thing, apparently).

But the Kaddish? That required some real commitment and effort. Also, it felt like something not to take lightly. Honoring the dead. My dead. I had to do it in good faith, or not at all.

My dad had provided some guidance regarding the question of Kaddish through his own example when his parents died. He had on occasion talked about envying other people who believed in God, because it “made things easier” for them at the end—implying that he wasn’t a believer himself, although he assiduously avoided coming out and saying it. On the few occasions when I broached the subject of God’s nonexistence with him, he’d listen and perhaps nod. He never came out and disagreed with what I was saying, but he also never explicitly stated his own belief, or lack thereof. When his parents died, he became more conscientious about going to shul, at least every Friday night; he never went as far as seeking a morning minyan, though.

Dad died in the first hour of Yom Kippur in 2018; it was his 85th birthday. I think he deliberately held on until that day, and then relaxed his grip on life; Lenny always had a plan. I gave the eulogy at the funeral the following day; the weather was warm and hazy. Many of his “neighbors” in the cemetery were also South Africans, and some of them had been very close friends. I said the Kaddish first at the graveside, and then again in the evening, in the garden of my parents’ beautiful little house on the Hudson. We stood at dusk, the mighty reach of river flowing past the wall that had been built to keep it in check after the ravages of Superstorm Sandy. These were public recitations, de rigueur and prescribed; it never even occurred to me to not recite them. In that sense they were purely ritualistic, like the Kiddush and the Seder.

But saying Kaddish for the next 11 months was a separate question.

I’d like to say that I actively wrestled with the issue of whether or not to embark on nearly a year of reciting the Kaddish, but that wouldn’t really be true. I think I’d always assumed, deep down, that I’d inevitably give it a try, that it probably wouldn’t take, and that I’d find a way of rationalizing my failure after the fact (and key to that rationale would be framing it as anything but “failure”; I’m pretty good at those sorts of rationalizations).

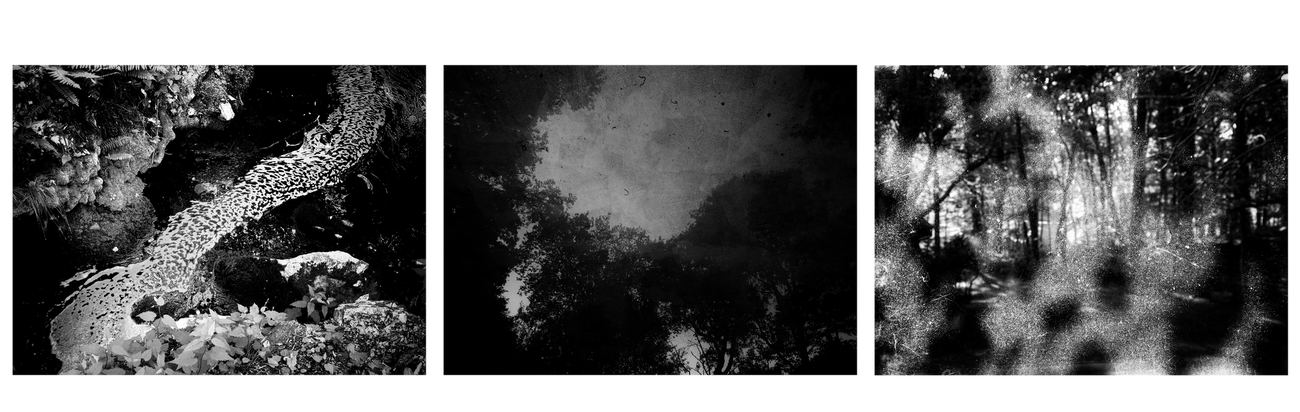

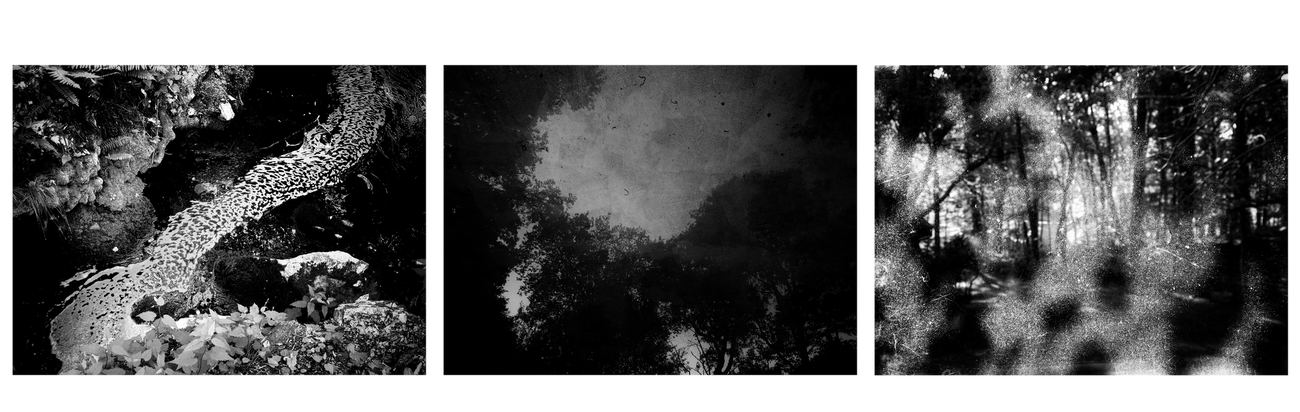

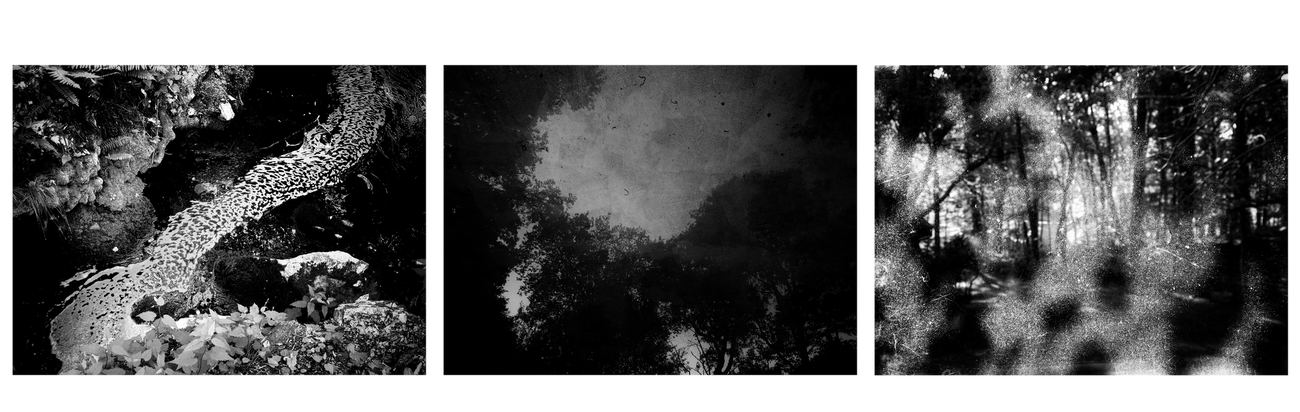

The day after the funeral, I walked up the steep wooded hill behind my house in northern Westchester County, where the New York metropolis melts into the countryside. I needed a moment of reprieve from the enervating drama and oscillating emotions of my dad’s last few months. At the rocky outcropping where I’ve spent countless hours in mindless reverie, with its great view to the southern reaches of the Hudson Highlands and the distant hills on the other side of the river, I started to recite the Kaddish. My voice was strong and unwavering; I didn’t feel the mawkish self-consciousness I had always anticipated. The ancient words just flowed out of me. The imperative opening, Yitgadal v’yitkadash shme rabah. Amen. I kept going, just as I’d muttered along for almost half a century; the words were practically tattooed on the inside of my cranium. The next section, more matter-of-fact: B’almah divrah chirutay ...) And then my favorite part, the incantatory “yitbaRACH v’yishtaBACH v’yitpoAR v’yitroMAM v’yitnaSEH,” guttural, percussive, assertively rhythmic, the cadences of a camel loping across an interminable desert. My appreciation for the prayer is willfully divorced from its literal meaning—I have a residual memory of the translation, but to have kept that in mind would have been to eviscerate it of the meaning that I was starting to project onto it. My first solo Kaddish ended. I felt the breeze, light on my face.

I understood, in that instant, that my own ritual, my own practice, had started to take shape.

I paused at the end, and then quite naturally slipped my iPhone out of my pocket. I took a photograph of exactly what I’d been looking at as I recited—not aiming for a great photograph, but just to record the moment. I immediately converted it to black and white, fiddled a little with the contrast and levels, and there it was.

There was one piece missing: the biblical requirement for a congregation, a minyan. I didn’t know where the local congregations were (which took some willful oblivion on my part, as northern Westchester is replete with synagogues), but I knew where to find people on social media. I posted the photograph I’d just taken on Instagram, with the hashtag #kaddishforlenny.

I understood, in that instant, that my own ritual, my own practice, had started to take shape.

Without any real conscious effort on my part, I had fallen into a space that ended up sustaining me for the 11 months and one day of Kaddish. I did it every day (no skipping for Shabbos or the High Holidays, which, technically, are supposed to be skipped). Every day, when the moment felt right, I’d recite the Kaddish, take a photograph of the there-and-then, and post on Instagram. My minyan quickly coalesced—a loyal band of family, friends, and acquaintances around the world who checked in every day and “liked” that day’s image as a way of bearing gentle witness. Sometimes there would be a comment on a particularly resonant image. Many days I found myself in those same woods up behind the house, sometimes looking at a stand of mushrooms muscling their way out of the ground, or a particular twisted vine. One day I walked with my mother along the Hudson, under a mackerel sky. Some days found me in my study at home, reciting the Kaddish as rain sluiced crazy patterns down the large picture window with its view of the old stone wall and our road. Icy puddles. My shadow. Fiddlehead ferns. Even, once, the artificial shrubbery in my shrink’s office. Sometimes I chose the moment spontaneously, sometimes I’d contrive to be in a certain place where I knew I’d get a better photograph, and then say the Kaddish there. On some occasions I’d recite in the presence of others. My wife, my stepdaughters. My Palestinian son-in-law (in fact, very early on I modified the Kaddish by adding the words “v’Falestin” (“and Palestine”), to the last line so it now said “May he who makes peace for us and for all Israel and Palestine …”) At the very end of the 11 months many of the people in my Instagram minyan wrote to say that they’d appreciated the opportunity to be ambient fellow-travelers on this deeply moving journey.

Infusing this all, of course, was a single conscious deliberation while I was reciting: a deep concentration on my father, on the gentle magnificence of Lenny Seimon. The grief that suffused that autumn melted into a profound sense of appreciation by the time spring arrived. In other words, the very reason that Kaddish, the traditional Kaddish, has evolved the way it has—with the daily repetition and the almost yearlong duration—revealed itself to me. The Kaddish kept me focused, but also allowed me, very gently, to let go. And every day, as I ended my practice, I’d look up, then close my eyes and say thank you. Thank you, Lenny. Thank you, Dad.

Jon-Marc Seimon, digital media strategist, UX designer, and photographer, contemplates the benign indifference of the universe from his perch in the Lower Hudson Valley.