Shalom Chaver!

In this week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study, how Jewish conceptions of friendship and trust are tied up in ritual purity and levels of religious observance

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

Since I began the Daf Yomi cycle, I’ve been wondering how accurately the Talmud reflects the actual practices of the Jews of its time. The rabbis in the Talmudic academies spent their lives learning the complex laws governing everything from Sabbath boundaries to ritual sacrifices, and even they often disagree on the exact scope of those laws. How could the average Jewish farmhand or wagon driver be expected to know all the details, much less to observe them? The question is especially interesting for modern American Jews, who generally don’t observe Jewish law very carefully, but still see themselves as part of a Jewish community. Was it the same for our ancestors in ancient Babylonia?

The question is impossible to answer fully, but the Talmud offers some hints. The rabbis often refer to a kind of Jew they call am ha’aretz, which literally means “people of the land,” but carries the implication of a person who is ignorant or careless about Jewish law. Even an am ha’aretz, one imagines, could not have been nonobservant in the way many modern Jews are. Living in a Jewish community, as almost all Jews did in ancient times, meant that certain communal norms were automatically enforced. For instance, in Tractate Shabbat, the rabbis pondered the question of whether it was possible for there to be a Jew who was ignorant of what Shabbat was, and decided it was not, unless he had been kidnapped by gentiles in infancy. There must have been people who were more or less strict about carrying in public domains, or creating eruvim; but open defiance of Shabbat was a capital crime and must have been basically nonexistent, even for an am ha’aretz.

Just what defines an am ha’aretz, then? This week, Daf Yomi readers received a detailed explanation. It came in Chapter 4 of Tractate Bekhorot, in the course of a discussion of the rules about giving firstborn male animals to a priest. As we have seen over the last few weeks, the Torah commands that Jews donate the firstborn male offspring of every kosher animal to the priesthood.

But when exactly is this to be done? The mishna in Bekhorot 26b explains that an animal should not be donated as soon as it’s born; this is considered undignified, and it also shifts the burden of raising the animal until it’s old enough to be eaten. Rather, the mishna establishes a timeline: Small animals like sheep or goats should be donated after they are 30 days old, while cattle should be 50 days old. “If the priest says to the owner within that period, Give it to me, that owner may not give it to him,” the rabbis emphasize. There is also an outer time limit: The Torah says “you shall eat it before the Lord your God year by year,” which the rabbis interpret as meaning that the animal must be eaten within the first year of its life.

Firstborn animals could be given to any priest of the individual’s choosing, which naturally, opens up the prospect of favoritism and even bribery, since priests would be able to compete for donations. Indeed, the Gemara in Bekhorot 27a suggests that this must have been a problem, since it is specifically prohibited for a priest to pay a Jew for the right to take his animal. Payment would transform what is supposed to be a gift into a commercial transaction. However, there is a loophole, since it is permitted for a priest’s relative to pay on his behalf.

Another possibility for abuse arises when it comes to determining whether an animal is blemished. A firstborn animal given to a priest for sacrifice must be unblemished—that is, without a physical defect. If it is blemished, the owner is supposed to let it graze for a year, until it becomes too old to sacrifice, and then he can eat it. Determining whether an animal is blemished is a complicated job that the Talmud says only an expert can perform—“an expert like Ila in Yavne,” who must have been renowned for his skills. But there’s clearly an incentive here for an animal’s owner, who benefits if his animal is found to be blemished, to pay the judge to reach that conclusion. That is why judges cannot be paid according to the verdict they render, but have to receive a fixed fee in advance, regardless of whether they find the animal blemished or unblemished. That was Ila’s practice: He received four issar for examining a small animal and six for a large one.

By the same principle, the rabbis go on to explain, no Jewish judge is allowed to receive fees from litigants. “One who takes his wages to judge, his rulings are void,” says the mishna in Bekhorot 29a, just as one cannot pay a witness to give testimony. This suggests that judges have to work for free, which would naturally make it hard to find a qualified person willing to take on the work. This is especially true since, as the mishna says in Bekhorot 28b, a judge who issues a mistaken ruling that causes damage to a litigant is personally liable—he “must pay damages from his home,” that is, from his personal funds.

This is a very different way of thinking about a judge’s role than we are used to in modern American law, where judges are paid civil servants with no personal financial stake in their work. And in fact, the Talmud comes to a similar conclusion, ruling that while judges can’t be paid fees according to their verdict, they can receive compensation for their time: The litigant must “give him his wages like a laborer.” The Gemara clarifies that this means he should be paid for the time he lost from his usual occupation by judging, in the amount he could otherwise have earned.

The same principle applies to teaching Torah: It is a sin for someone learned in Torah to charge fees for teaching it. In Deuteronomy, Moses tells the Israelites, “I have taught you statutes and ordinances as the Lord my God commanded me”; just as God taught Moses for free, the rabbis deduce, so Moses taught the Israelites for free, and so should all future transmitters of Torah. As often happens in the Talmud, however, this noble ideal isn’t put into practice because of simple necessity: If no one could be paid for teaching, there wouldn’t be enough teachers. So an exception is made to allow teachers to accept a livelihood.

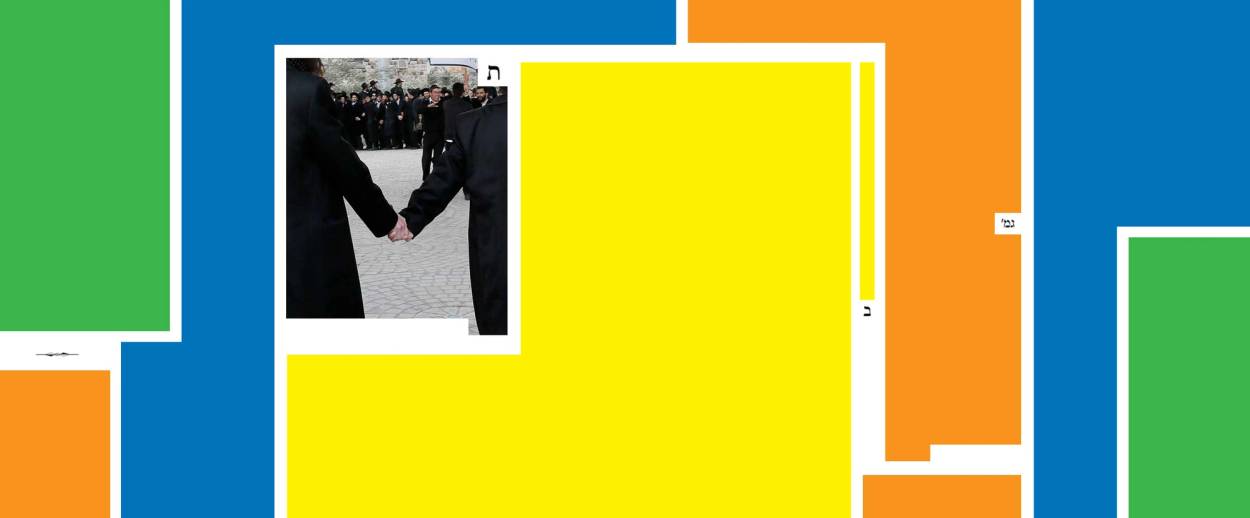

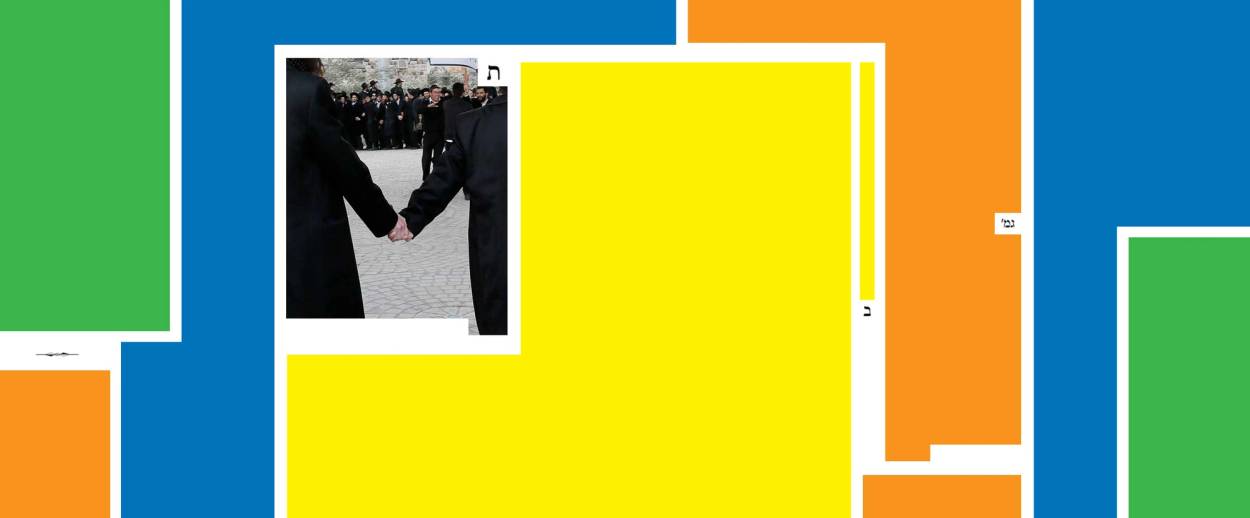

Finally, the chapter reaches the subject of who can be trusted to fully observe Jewish law. If someone isn’t strict in his observance of one area of Halakha, such as the sabbatical year, can he be trusted to observe another area, such as tithing? In the course of this discussion, the Gemara explains the concept of a chaver, who is the opposite of an am ha’aretz. A chaver—literally, a friend—is someone who “accepts upon himself” the responsibility of fully observing Jewish law, in particular the laws related to tithing and ritual purity. “Friends” could trust one another when it came to buying and selling produce and livestock, knowing that they would be properly tithed.

But how did one become a chaver? Obviously, the whole point would be lost if an am ha’aretz could claim to be a chaver without being trustworthy about observance. That is why becoming a chaver was a stringent process, requiring a promise to observe all the laws without exception. “One who comes to accept upon himself the commitment to observe the matters associated with chaver status except for one matter, which he does not wish to observe, he is not accepted,” the Gemara says. Further, to become a chaver one must first demonstrate proper observance at home: “If we have seen that he practices such matters in private, within his home, he is accepted,” and then taught the full obligations of being a chaver. The first step is to be “accepted with regard to hands”: That is, once an am ha’aretz proves that he is careful about washing his hands to avoid ritual impurity, then he can become a chaver candidate. Even then, there is a 12-month probation period. Clearly, even in Talmudic times, it was not a given that every Jew would be an observant Jew.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.