Talmud’s Warriors and Scholars

This week’s Daf Yomi reframes the debate over the primacy of force or scholarship in Jewish values

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

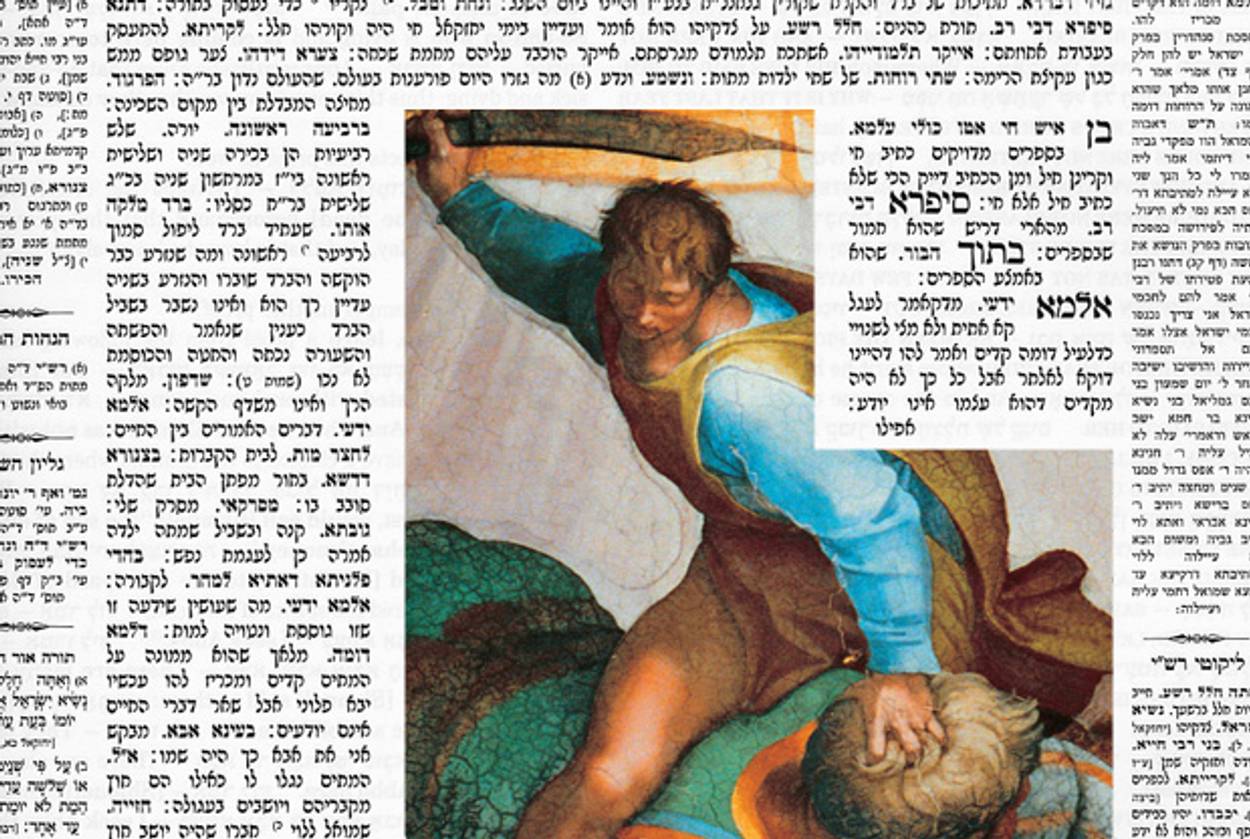

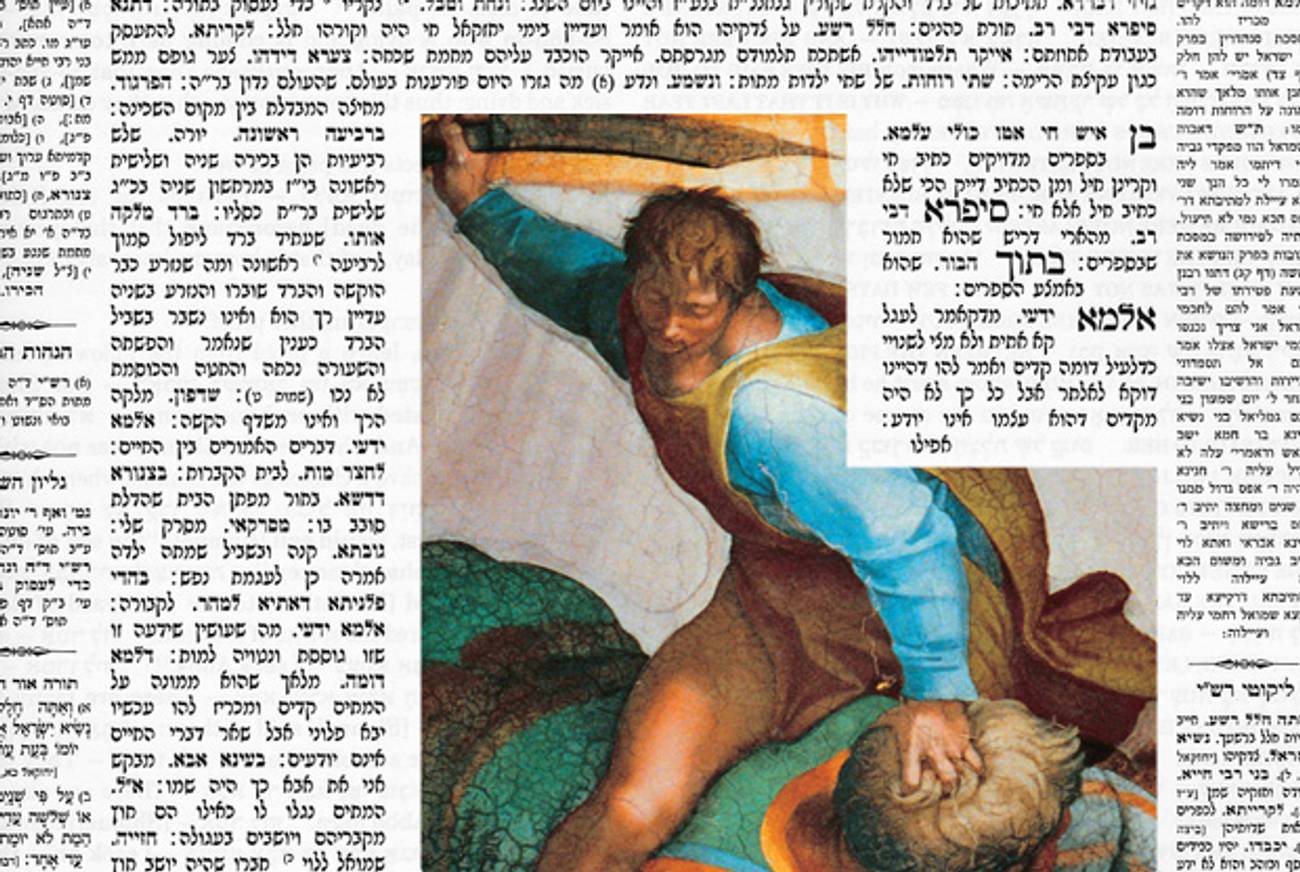

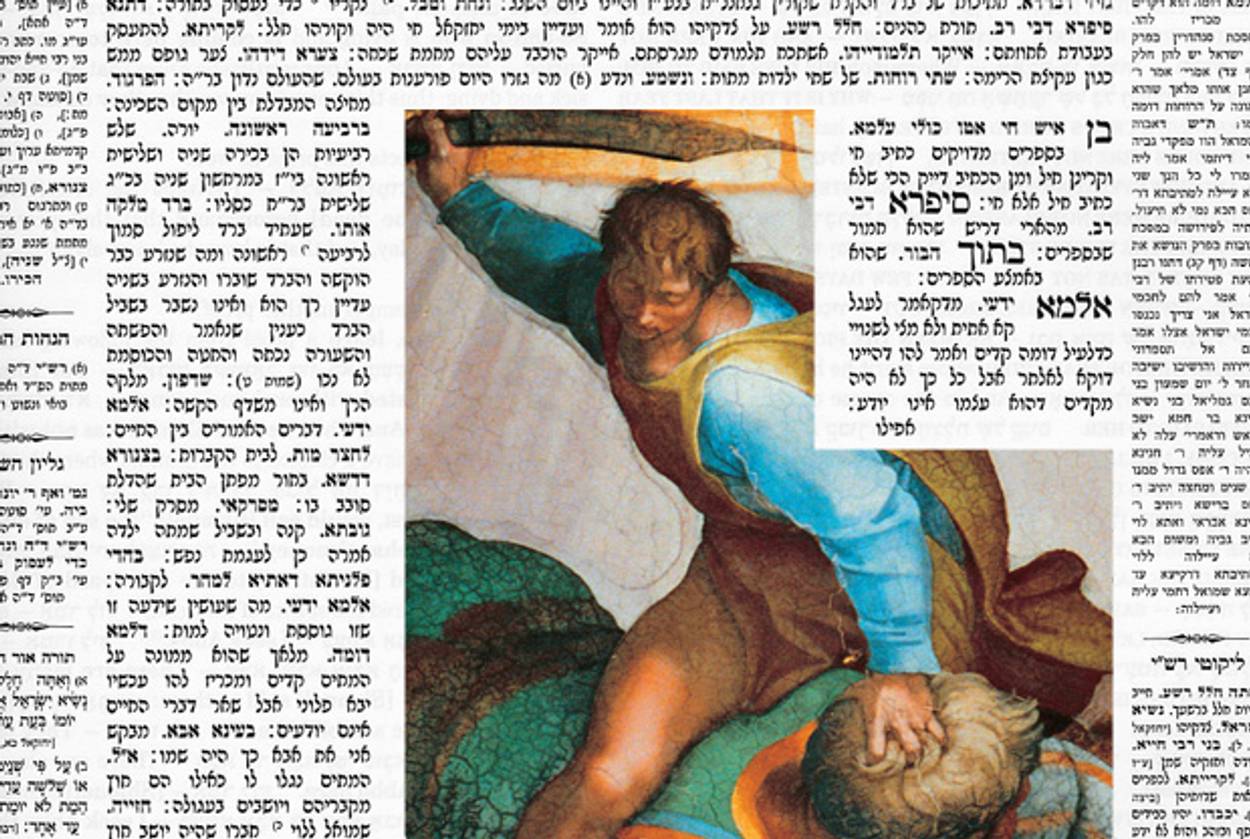

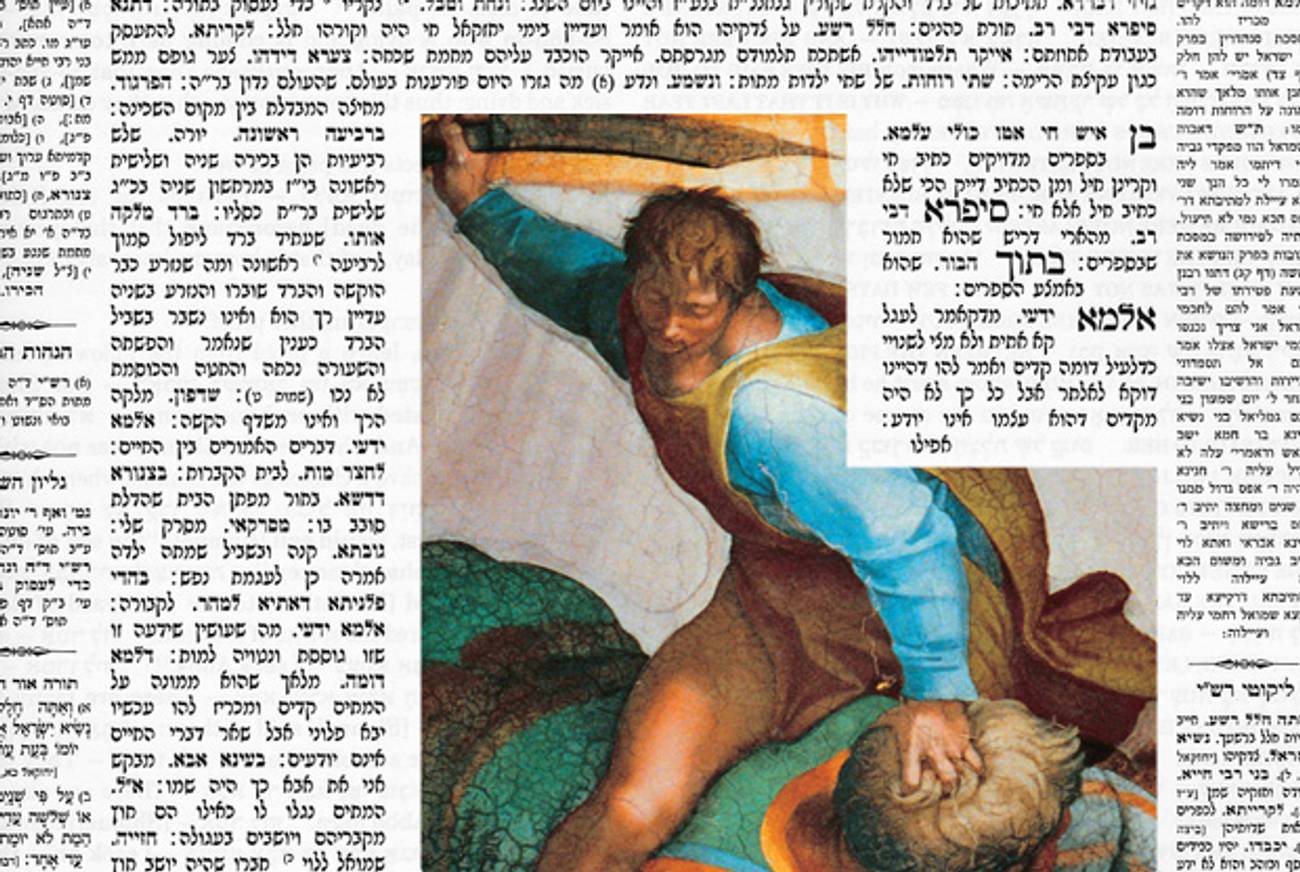

At the end of the second book of Samuel, after a report of King David’s last words, we are introduced to a roster of “David’s warriors,” the greatest fighters in his retinue. Nowhere does the Bible come closer to the heroic ethos of the Iliad than in this catalog of mighty deeds. Josheb-Basshebeth fought alone against 800 enemy soldiers; Shammah son of Agee singlehandedly defeated a Philistine army in a battle in a lentil field; three chiefs infiltrated a Philistine camp to get water for David to drink. Last in the list comes Benaiah son of Jehoiada, “a brave soldier who performed great deeds”: Namely, he killed the two sons of Ariel of Moab, and he went down into a pit on a snowy day and killed a lion.

Benaiah turns up rather unexpectedly in this week’s Talmud reading, in Berachot 18a. At first he enters the text not on his own account, but because the Bible happens to describe him as “the son of a living man.” Why, Rabbi Chiya asks, should the text bother to mention that Benaiah’s father is alive? After all, he says rather impatiently, “are the rest of the world then the sons of dead men?” No, Chiya argues, the reason is that Benaiah’s father was so righteous that he was called “a living man” even though he was actually dead. In this way Chiya contributes to an ongoing Talmudic debate about whether the righteous enjoy life after death.

More fascinating to me, however, is what comes next. In one of the lateral moves that can make a Gemara discussion so unpredictable, Chiya goes on to analyze the Bible’s description of Benaiah himself. And he does this in a way that turns the Davidic warrior into a Talmudic rabbi. Benaiah is called “a man of many achievements, from Kabzeel”; by changing the way the place name is read (a favorite hermeneutic technique in the Talmud), this can be understood to say mekabetz El, “a man of many achievements for God’s sake.” And such achievements, to the authors of the Gemara, can only be feats of Torah scholarship: “this means that he increased and garnered achievements for Torah.”

Reading in this allegorical fashion, Chiya argues that when the Bible says Benaiah struck down two men of Moab, it means that “he did not leave anyone comparable to himself [in scholarship], neither in the period of the First Temple nor in the period of the Second Temple.” When it says that he killed a lion in a pit on a winter day, this means that he immersed himself in a freezing pool, to purify himself before studying Torah. Alternatively, it means that he studied an entire treatise on the Book of Leviticus on a single freezing day.

This remarkable transformation of Benaiah from a killer into a scholar raised two questions for me. First is the perhaps unanswerable one of how Chiya understood allegory. When he argues that the biblical descriptions of Benaiah’s physical feats were really descriptions of mental and spiritual feats, did he think that this meant that the physical feats did not happen at all? If so, how do the rabbis understand the entire David story, which plainly belongs to a world of fighting kings and their armies?

If, on the other hand, Chiya understood that he was reading against the grain of the biblical text—that is, imposing on it a new meaning and a new system of values—the second question arises. How did he and his fellow rabbis think and feel about the enormous change in Jewish life that had made warrior-heroism so archaic and scholar-heroism so important? Clearly, between the time of the Israelites and the time of the Amoraim, there was a revolution in Jewish values, in which something was lost as well as gained. From a Zionist point of view, it’s even possible to feel that the denigration of Benaiah’s fighting spirit was a dangerous mistake for the Jews. Not until 1948 would the Jewish people once again produce warriors on Benaiah’s scale.

Yet reading the Talmud has also made me more inclined than I used to be to see this question from the other side, from the rabbinic point of view. After all, if Torah study is the most worthy and most distinctively Jewish of human pursuits, then mere skill at fighting is negligible, a barbarism. Which, finally, does Judaism need more, warriors or scholars? Which is a higher human type?

The Talmud’s answer seems clear enough. Indeed, in this week’s reading, there is a section that acts as a rabbinic parallel, and rebuttal, to the praise of David’s warriors in the book of Samuel. This is the account, starting in Berachot 16b, of the personal prayers that some of the most famous rabbis would recite after saying the Shemoneh Esrei, what we now usually call the Amidah.

David’s warriors are defined by the number of men they killed, a kind of statistical heroism that makes them all blend together: This one slew 300 Philistines, that one slew 800. The rabbis, on the other hand, are individualized by their prayers, which seem to communicate something of their distinctive personalities. Rabbi Elazar prayed hopefully, asking for love and brotherhood, a large number of students, and a portion in the Garden of Eden. Rabbi Yochanan prayed darkly, asking God to “gaze upon our shame and behold our evil plight.” Rabbi Chiya—appropriately, given what we have learned of him—prayed that “Your Torah be our preoccupation.”

Is it possible to be too preoccupied with Torah? This is not merely an abstract question. It’s possible to trace a direct line from Chiya’s interpretation of Benaiah to the debate currently roiling in Israeli politics about whether ultra-Orthodox students should be drafted into the army. Reading the Talmud has already given me a greater appreciation of the logic behind the Haredi resistance to being drafted. For the authors of the Talmud, Torah study was not only the best thing men could do, it was the best means to preserve the Jewish people as well. Those who maintain today that Torah study is what keeps Judaism alive have a good deal of history on their side. On the other hand, history also teaches that Judaism cannot live unless Jews live, and that force is sometimes the only way to preserve life. Benaiah and Chiya may need each other more than either one suspects.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.