Under a Spell

The long history of Jews and the occult

While some Jewish families see Halloween as a pagan holiday that should not be observed, the fact is, Jewish tradition is itself no stranger to the otherworldly, with its own history of golem-makers, sorcerers, and demon wranglers, and throughout the centuries Jews have been as afraid of evil spirits as anyone else.

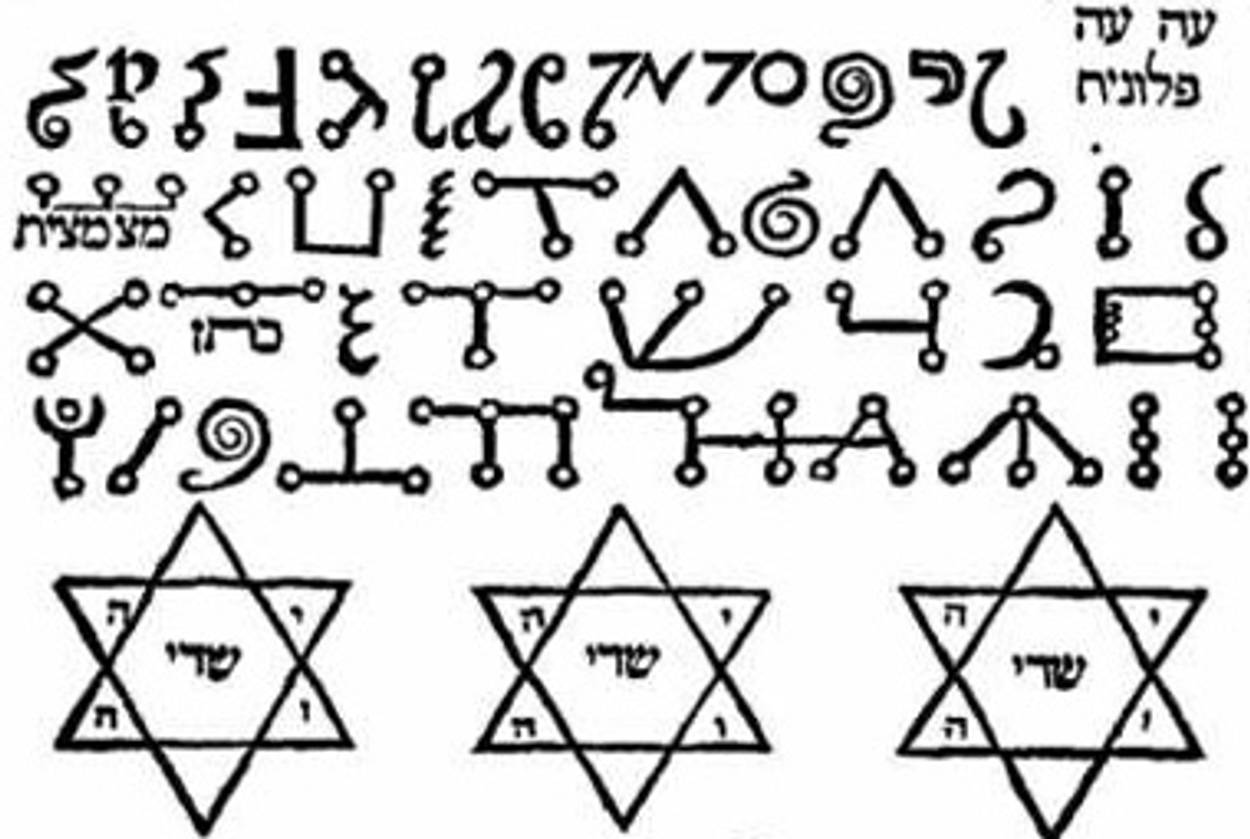

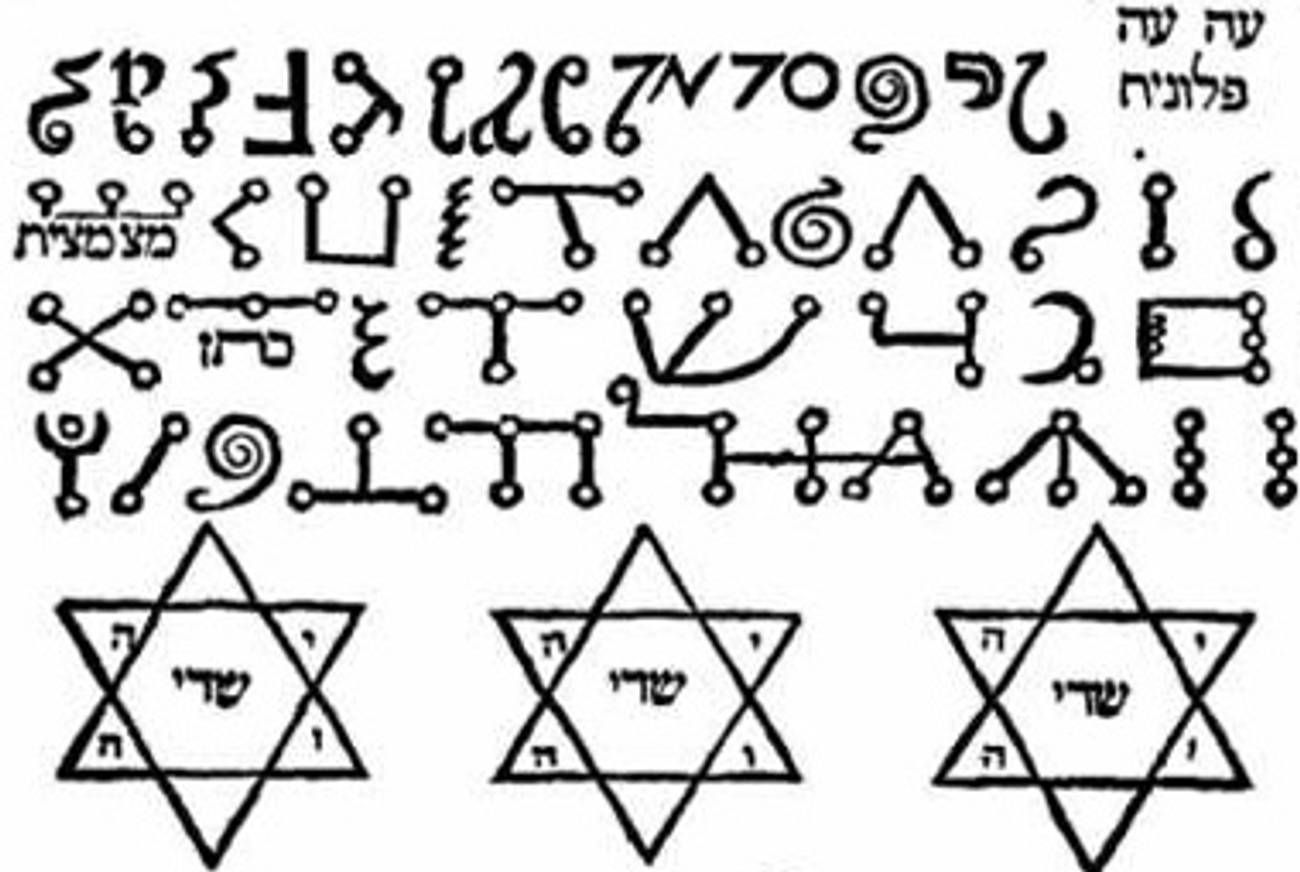

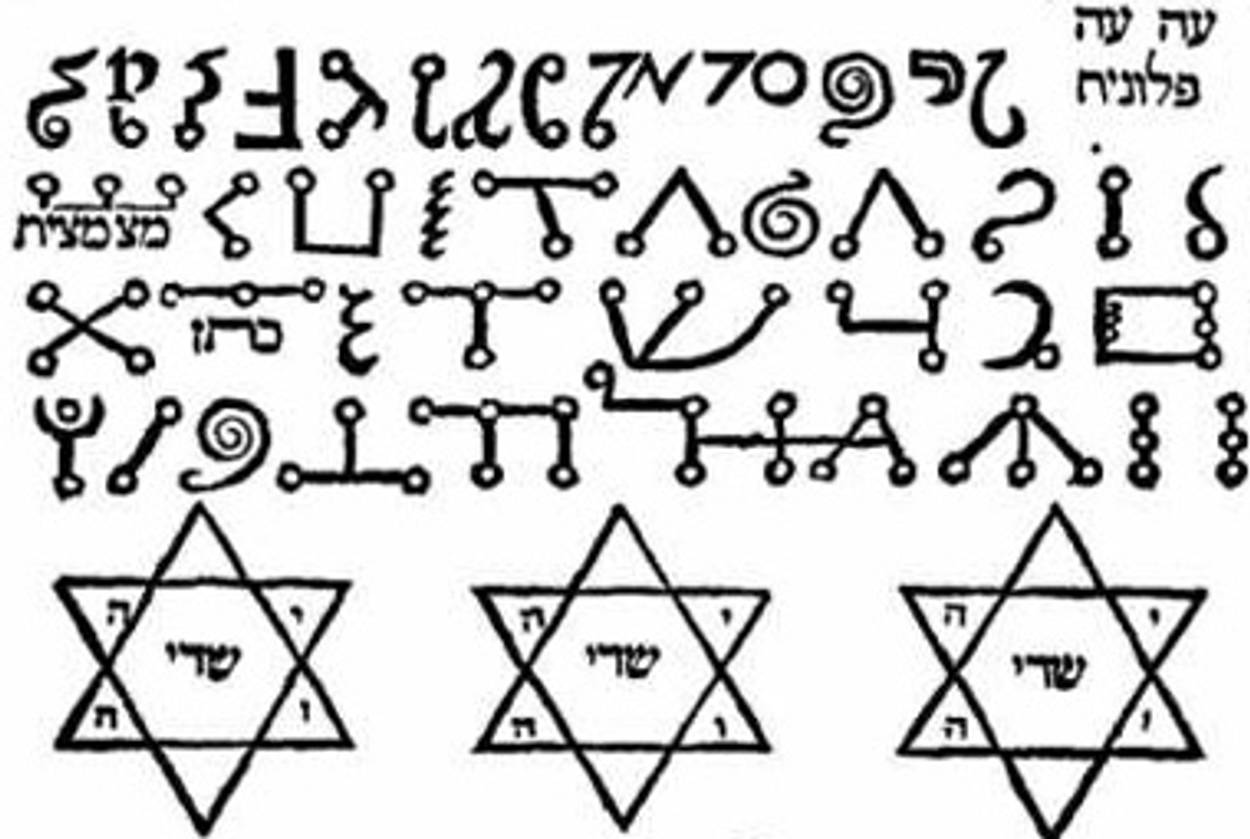

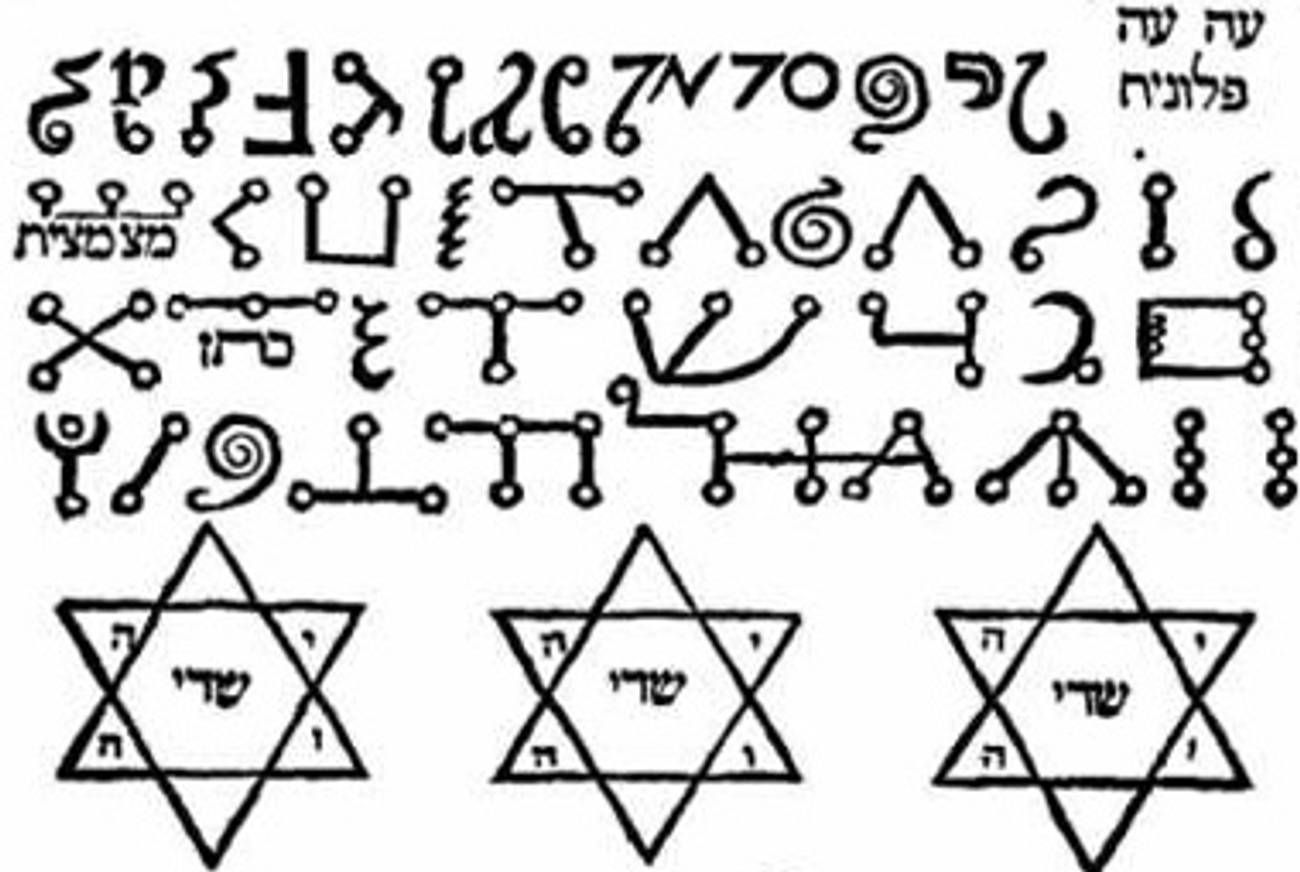

As early as the Roman period, Jews used amulets as a best defense against evils—both real and supernatural—that lurked outside their doors, a practice that continued into the late 17th and 18th century. The amulets could be made on flattened bits of metal inscribed with the names of angels or on small, encased scrolls, much like the mezuzah. But there were other kinds of magic as well. Medieval Jews called out God’s name and those of His angels to smite enemies and to gain affections. In addition, Jews of all ages practiced astrology and looked for omens in the form of animals. Since traditional liturgy made little room for personal prayers, these extra-liturgical means helped people combat what they saw as constant threats.

It was the Jews of the Middle Ages, however, who helped to create a more systematic approach to magic. Mystical writings have always detailed the strange and mysterious levels of heaven, but it was Jewish magicians who provided the correct formulas and rituals needed to pass through the gates. They had to make magic seals (small tokens engraved with Hebrew names), which forced the angel or demon on guard to flee, belying the essential belief that Hebrew letters are filled with divine energy that can be manipulated for various ends, from conjuring demons to making golems. This form of Jewish magical practice, along with mystical and kabbalistic texts, was to be a major influence on later non-Jewish occult practitioners. And this is a phenomenon that really took root during the Renaissance.

What we typically refer to as Western occultism—that is, the body of knowledge related to the supernatural workings of the universe—started in the Renaissance, an era that maintained both an abiding interest in astrology, magic, and alchemy and a growing interest in empirical thought and Greek philosophy. To Renaissance thinkers, the natural world was a reflection, or imitation, of the divine and through certain magical practices—such as communing with spirits and astral projection—a person could achieve true salvation. At the same time, Jewish mystics similarly believed that God is inseparable from his creation, and the non-Jewish Renaissance magicians looked to Jewish mystical texts to map out proof that of that fact and to glean secrets about God through magic; such texts offered very specific instructions, often involving the use of seals and the recitation of angelic and divine names, which were used to try to understand the divine. These ideas and symbols wound their way through the centuries, through fraternal and secret societies, and the Freemasons, theosophists like Madame Blavatsky and Aleister Crowley, and New Age Wiccans incorporated Jewish mystical and magical elements into their own mythologies.

Among the methods that mystics used in their quest for understanding was gematria, the art of finding hidden meaning by assigning numerical value to Hebrew letters. For non-Jews, performing gematria on Hebrew words that seemed to correspond to occult ideas became central to magical practice. It mattered little whether or not the meaning of the words was understood within the context of the Jewish religion or the Torah. Judaism was irrelevant to what was perceived as mysterious. Even more significantly for non-Jewish occultists, Hebrew letters took on a kind of occult power. Adorn something as simple as a pentagram with the tetragrammaton (the name of God rendered in the Torah as yod, heh, vav, heh) and you suddenly have a symbol that looks like it has great magical power.

Such beliefs persisted at least until the late 19th century, when many Jews became intent on embracing modernity and rationalism. By the time of the immigrant wave to America in the later part of the 19th century, the superstitions of the shtetls—that dybbuks could take possession of the body, or that the demon Lilith would come for misbehaved children, for instance—were largely left behind. Still, American immigrants couldn’t leave it all in Eastern Europe and many Jews in North America grew up tossing salt over their shoulder to ward off the evil eye and avoiding touching themselves when describing the illness of another person lest they contract the same affliction.

As Judaism struggles between assimilation and the preservation of tradition, Jewish magic suggests that Jews are very much like everyone else in so many beliefs. Ghosts, evil spirits, bad luck, and good are a part of a world view that co-exists with an omnipotent God and a complex moral system. And despite how far into the modern world Jews have moved, they continue to hear the echo of Sefer Hasdim, the famous medieval text, which advised, “One should not believe in superstitions, but it is best to be heedful of them.”

Peter Bebergal is the co-author of The Faith Between Us. He blogs at mysterytheater.blogspot.com.

Peter Bebergal is the co-author of The Faith Between Us. He blogs at mysterytheater.blogspot.com.