Why St. Patrick’s Day Is My Jewish Family’s Favorite Holiday

The parade was what my father first saw when he arrived from Nazi Germany

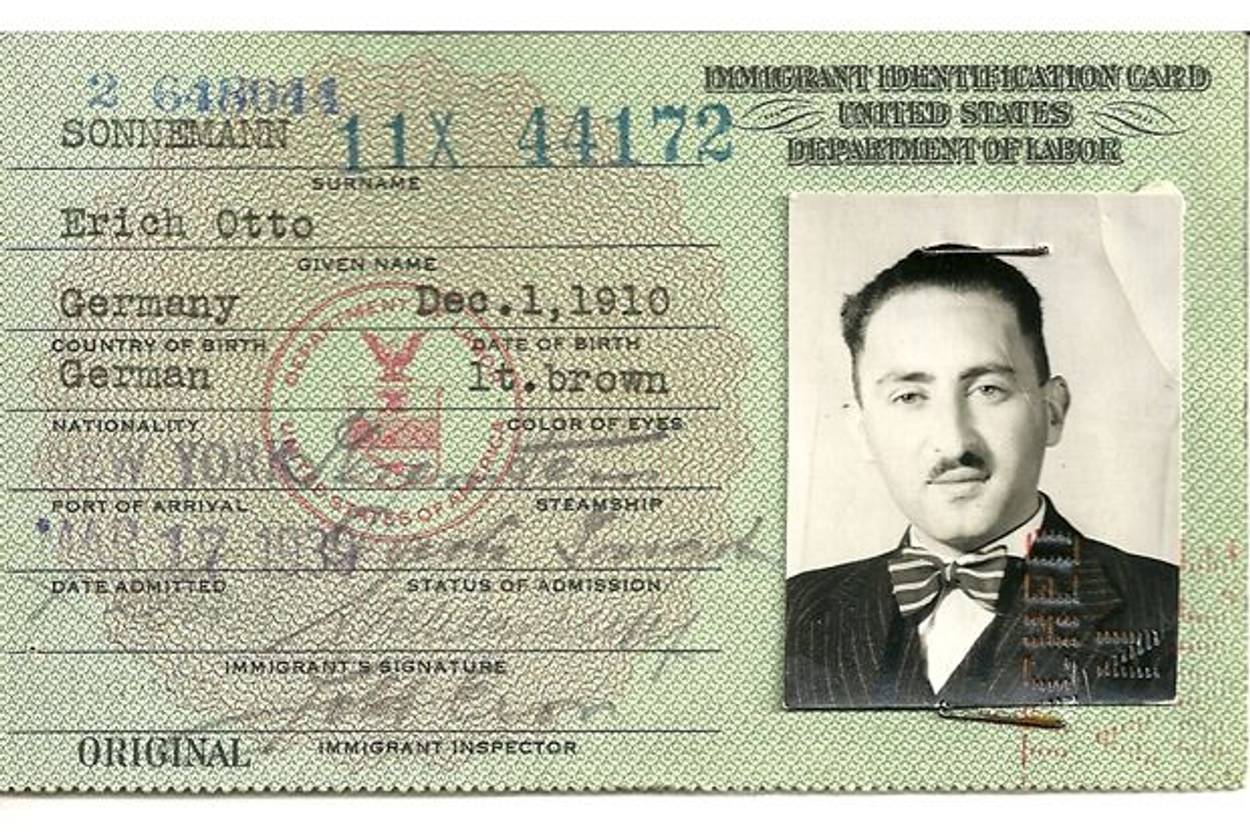

My father arrived in America from Germany in 1939, 75 years ago. It was March 17, St. Patrick’s Day—a holiday my father had never heard of—and New York City’s marching bands and colorful parade amazed him. If this was how America welcomed immigrants, it was truly fantastic.

St. Patrick’s Day would become my family’s special holiday, as unfailingly celebrated as Thanksgiving or the Fourth of July in our Chicago home. It was a day to wear green, see the Chicago River dyed emerald, watch the parade, and throw a party for my father.

Yet in the story of my father’s escape from Nazi Germany—a story he told hundreds of times until his death at 93—the bright St. Patrick’s Day arrival was inextricably linked to the dark memory of Kristallnacht, the violent night that marked the beginning of the Holocaust.

The two events were knotted together by luck, a confluence of circumstances and chance as unlikely and rare as the four-leaf clover that my father adopted as a personal symbol of his journey to America. That’s because on November 10, 1938—the very morning after Nazi storm troopers burned synagogues across Germany and Austria, trashed and looted Jewish homes and businesses, and sent some 30,000 Jewish men to concentration camps—my father had an appointment at the American Consulate in Stuttgart, Germany, 60 miles from his home in Mannheim, for his visa application.

My father’s boyhood friend, Karl, had joined the Nazi Party at age 18. He and my father argued bitterly, yet remained uneasy friends. Karl even took my father to hear the Nazi leader speak. Hitler “had everyone spellbound against the Jews,” my father would tell me. “They were the evil of everything wrong with Germany. On and on. Raving.”

“This Hitler is nuts,” he told Karl. But in 1933, when Hitler rose to power, Jewish professionals were fired, Jewish businesses “Aryanized” by forced sales. My father, a pharmacist’s apprentice, was summarily fired. He found another job, but was fired again in 1935, for the same reason.

“Get out of Germany, Eric,” Karl urged him. “We’re going to bury the Jews.”

But where could they go? Applicants for U.S. visas needed affidavits—usually from wealthy American relatives—promising support so the immigrant would not become a public charge. This requirement, often harshly interpreted, meant that quotas for German immigrants were never filled.

An affluent American relative? My father’s parents could think of no one.

Then, as if in a fairy tale, his mother awoke one morning having dreamed of an American woman who’d visited her family many years before. After a query to a cousin, they learned the visitor was Lucille Loveman, a distant and wealthy relative from Nashville, Tenn.

My father immediately wrote asking for help, and without any further questions, Mrs. Loveman sent an affidavit. It was 1937 when my father applied for a visa, and it would be a year before his number came up.

On November 8, 1938, Karl came to my father’s apartment to warn the family of the violence to come the following day. He urged them to hide and offered to take their valuables—gold rings and watches, a braided silver breadbasket, Shabbat candlesticks—for safekeeping. He wished them luck.

The next day and night, the family hid in the attic, nearly paralyzed with fear. But the following morning, my father had to keep his long-awaited visa appointment. On his way to the train station he walked alone through streets littered with shards of glass and burnt rubble, past the destroyed synagogue with its burned Torahs. He stopped to rescue a Torah that was still intact, hiding it among the ruins.

The American Consulate was ominously quiet. Usually, the building was jammed with applicants, a line flowing from the second floor offices to the street, winding around two blocks. Today, though, there were only two SS officers guarding the door. Bravely, my father strode past them.

He did not get a U.S. visa that day. A physical examination determined that he needed a hernia operation, and he went straight from the consulate to the hospital. But six weeks later, his visa was granted, and my father said goodbye to his family and left Germany for Holland, boarding a ship bound for America in late February 1939. Because of storms at sea, the passage lasted longer than expected and the ship arrived in New York on St. Patrick’s Day, Its passengers greeted by a band playing Irish music at the pier. My father’s uncle, a recent immigrant himself, insisted they go to Fifth Avenue to see the spectacular parade.

“I thought this is a wonderful country, to welcome the immigrants with a band and a parade!” my father always said.

Of course, America was not always so welcoming to many of the Jewish immigrants desperate to flee Nazi-controlled Europe. And my father’s happy ending depended heavily on luck—his mother’s dream of a wealthy relative in Tennessee, plus the unlikely help of a Nazi friend (who did, by the way, return the valuables).

Yet in remembering my father’s story I’m reminded that mourning one’s losses does not preclude finding joy where one can. And so for my family, St. Patrick’s Day will always be sufficient reason to celebrate.

Toby Sonneman is the author of Shared Sorrows: A Gypsy Family Remembers the Holocaust.