Your Weight in Onions

This week’s ‘Daf Yomi’ Talmud study explores many ways to pay off a divine debt: in gold, silver, pitch, vegetables—or limbs

Literary critic Adam Kirsch is reading a page of Talmud a day, along with Jews around the world.

In the first chapters of Tractate Arakhin, we learned about the vow of valuation, in which one promises to donate the value of himself or someone else to the Temple. As we saw, these values are determined according to a sliding scale that is established in the Torah, with adult males worth the most—50 shekels—and females under the age of 5 worth the least—only 3. This financial hierarchy isn’t meant to correspond to the innate value of the lives in question—it might, instead, be seen as a rough-and-ready approximation of the earning power of each category. But it certainly reflects the priorities of a patriarchal society, since at each age level, male lives are worth more money than female lives.

In Chapter 5 of this brief tractate, the focus turns to other kinds of pledges that a person can make based on his own person. For instance, the mishna in Arakhin 19a refers to one who says “it is incumbent upon me to donate my weight.” Perhaps such a vow might be taken on recovery from a serious illness, when a person wanted to express that he owes his entire bodily existence to God. With a vow according to weight, one would ordinarily specify the material to be donated: “if silver silver, and if gold gold.” For a full-grown person, donating one’s body weight in gold could turn out to be quite an expensive proposition.

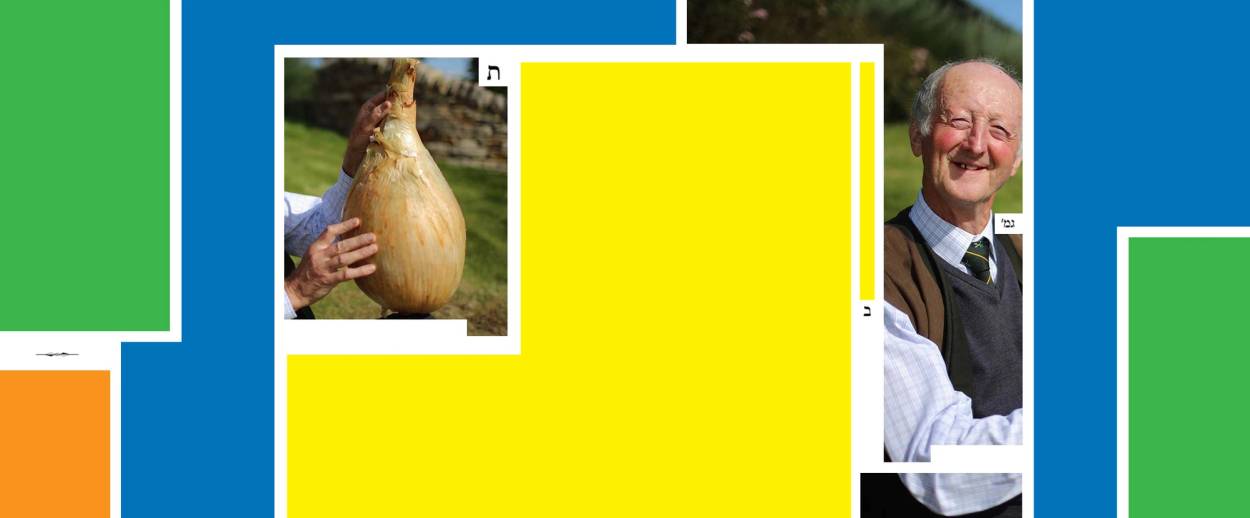

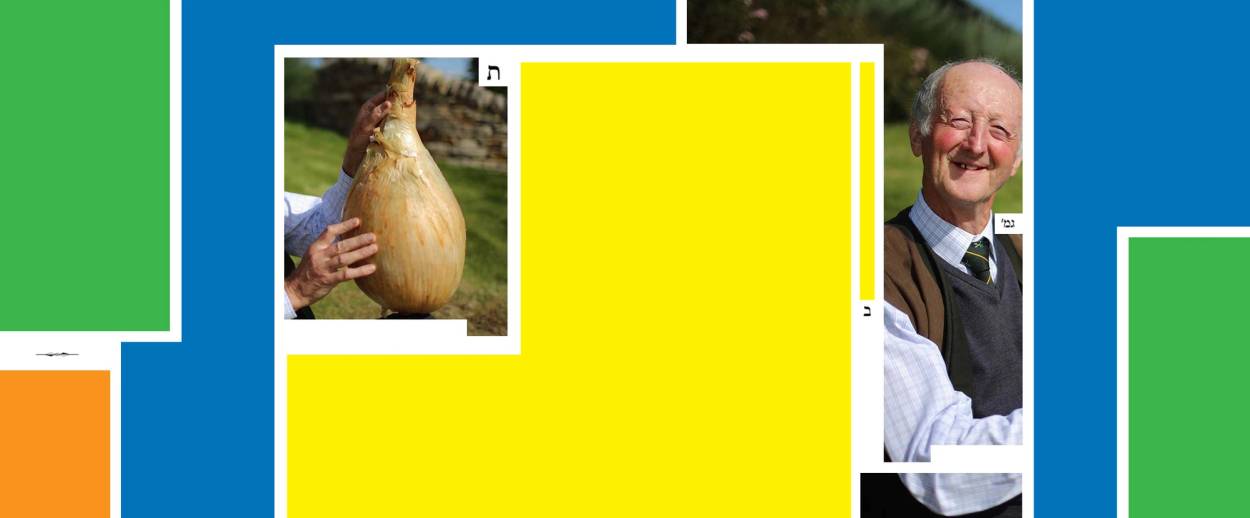

But what if you promised to donate your weight to the Temple and neglected to specify the material of the gift? In that case, the Gemara deduces, “if he did not specify the means of payment, he may exempt himself with any material.” The only requirement is that it must be a material that has a monetary value and is used in commercial exchange. For instance, “in a place where merchants weigh pitch when selling it,” you could get away with donating your body weight in pitch—a much cheaper alternative to gold. Rav Pappa adds that you could even give your weight in onions.

In general, the rabbis say, one must pay ‘in keeping with his status’: a person who is rich enough to pay in gold shouldn’t try to get away with paying in onions.

But the rabbis hope to discourage people from taking a cheap way out of their vow. That’s why they tell the story of the mother of Yirmatya, who promised to donate her daughter’s weight but didn’t specify the material. She ended up going to Jerusalem and paying in gold, because she was a “distinguished person” and could afford to. In general, the rabbis say, one must pay “in keeping with his status”: A person who is rich enough to pay in gold shouldn’t try to get away with paying in onions.

In addition to your weight, you could also pledge to donate your height, which raises trickier questions of measurement. To figure out how much one’s height is worth, Rav Yehuda explains, you measure yourself with a “thick rod that cannot be bent” made of silver or gold. Alternatively, if you promise to pay your “full height,” you use a thin, bendable rod—which seems strange, since it means that “full height” would cost less than simply “height.” As for someone who promises to donate “my stature,” “my width,” or “my thickness,” the Gemara says that these terms are too ambiguous and leaves them unresolved.

Height and weight are fairly straightforward measurements. But what if someone vows to donate “the weight of my forearm” or “the weight of my leg”? How do you figure out how much a single limb weighs? The Gemara suggests an ingenious method based on the principle of displacement. You fill a barrel with water and put your arm or leg into it, which causes a certain amount of water to splash out. Then you remove your limb and add donkey flesh to the barrel until the water level is full again. By measuring the weight of the donkey flesh, you can figure out the weight of your limb. Of course, as Rabbi Yosei points out, this assumes that donkey flesh is the same density as human flesh, which may not be true depending on its composition: “Is it possible to match flesh with flesh, sinews with sinews and bones with bones”? But Rabbi Yehuda replies that in such a case “one estimates,” since precise measurement isn’t possible.

While vows of valuation assign an individual a monetary value based on the Torah’s sliding scale, it is also possible to make a vow of assessment, which determines the subject’s value based on what he would command in the slave market. Slavery, of course, was a common feature of ancient society, and the Talmud has no qualms about suggesting that a human being has a market value. This assessment must be carried out by a panel of nine judges plus one priest, presumably based on local market conditions. But what happens if you make this kind of vow based on a single limb, vowing to donate “the assessment of my forearm,” for instance? The mishna’s answer is simple: You assess “how much he is worth with a forearm and without a forearm,” and the difference is the amount that must be donated.

Which kind of vow is more stringent, a valuation or an assessment? As the mishna in Arakhin 20a points out, it depends on which aspect you are considering. For instance, if you make a vow of valuation on yourself and then die, your heirs have to pay it, since they know exactly how large the donation was supposed to be—all they have to do is consult the Torah’s table. If you make a vow of assessment and then die, however, your heirs are in the clear, since it’s impossible to determine the market price of a dead person: “There is no monetary value for the dead.”

In this sense, the vow of valuation is more stringent, since it survives death. On the other hand, the vow of assessment is more stringent in the sense that it can be applied to things other than human beings. The Torah assigns valuations only to people, but if you promise to donate the assessment of a bird or a sheep, you pay according to their market value. By the same token, you can’t make a valuation of an individual limb, but you can make an assessment.

But this applies only to limbs that could be theoretically removed without killing their owner, such as an arm or a leg below the knee. If, on the other hand, you promise to pay the assessment of your head, you must pay the value of your whole living body, since a body without a head couldn’t survive. Likewise, if you vow to donate “half of my valuation,” you simply divide your Torah-assigned valuation in half. But if you say you’re going to donate “the value of half of myself,” you must pay the full amount, because it’s impossible for half of a person to survive—in this sense, half a person is equivalent to their entire life.

***

Adam Kirsch embarked on the Daf Yomi cycle of daily Talmud study in August 2012. To catch up on the complete archive, click here.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.