Fridays With Zalman: The Spiritual Wisdom of Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

The legendary rabbi talks about free love, doing LSD with Timothy Leary, and mortality in a new book, ‘The December Project’

When my family moved back to Philadelphia from New York in the early 1970s so my father could be an assistant professor in the sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, it was natural that they would send my brother and me to pre-school at the Germantown Jewish Centre. Germantown was my father’s childhood synagogue; it was where he and his brother had their bar mitzvahs, my parents were married, and my grandparents were longtime (if not very active) members. But the synagogue had changed in recent years, as the burgeoning Jewish Renewal scene centered around the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in nearby Wyncote gained a foothold in Germantown’s havurot.

I remember seeing a close friend of my parents—then in his 20s, a generation younger than they were, childless and still cool in my eyes—dancing wildly on Simchat Torah, crazily drunk, leaping and lurching in ungainly ways in the circle, passionately celebrating. At 7 or 8, I was fascinated by him; I later learned he had also dealt in stronger substances to pay his way through college, so there may have been more than alcohol in his system. The point is, his drunkenness wasn’t just a physical condition—it was connected to Torah, to Simchat Torah, to ecstasy and crazy drunk joy. I was enthralled.

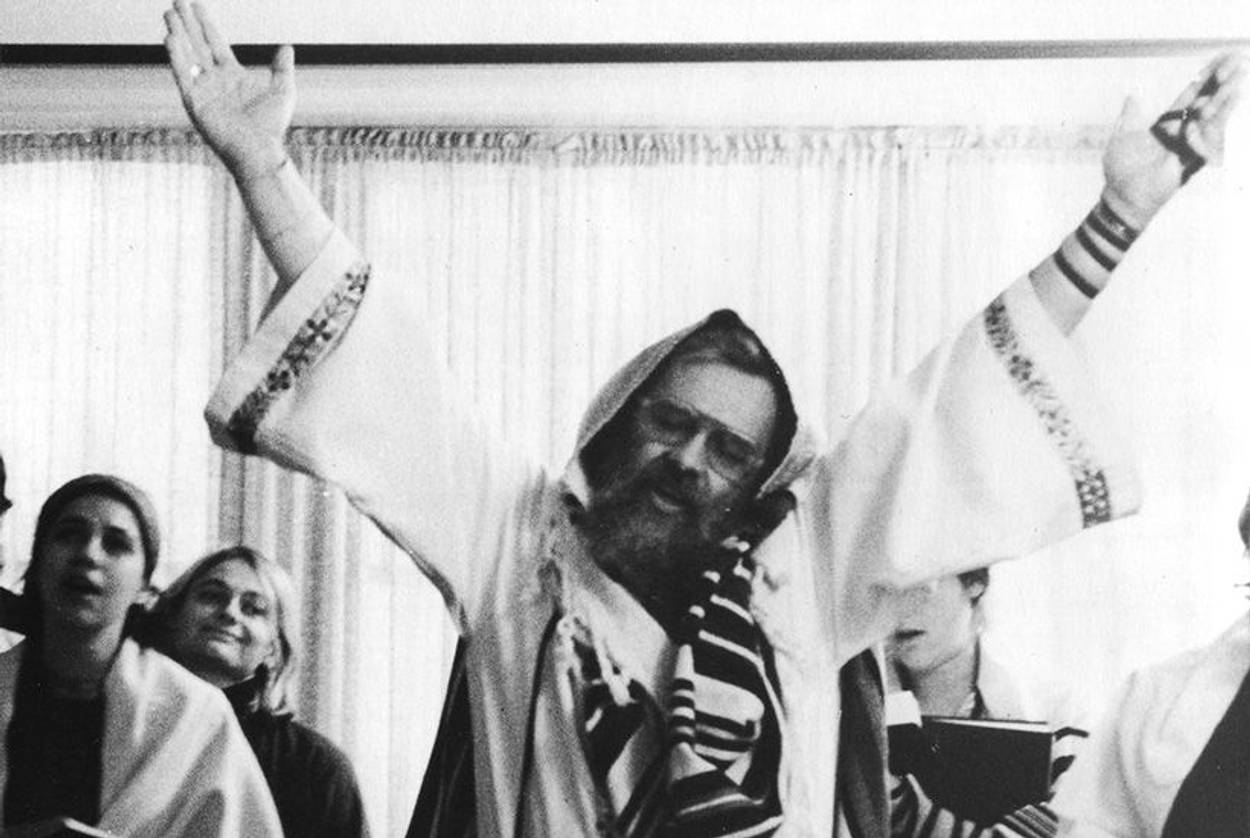

The spiritual figure behind what was going on at Germantown and in Jewish Renewal was Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, who was a member of Germantown and its havurot while he taught in Temple University’s religion department. As a kid, I remember him with a long gray beard, big Renewal-style kippah, sandals and white socks in any season, and a loud infectious laugh. We knew that the wife he was with was number three (he is now married to number four, with 10 biological children from his spouses and one more he fathered as a sperm donor for a lesbian rabbi), and that was an odd thing to me as a child. Still, the way the adults venerated the rabbi, known simply as “Zalman” for there was only one Zalman, made him a figure of interest in our Germantown circle.

In a sense, Schachter-Shalomi is the Zelig of the Jewish world: He has been present at every moment in 20th- and now 21st-century Jewish history—whether in Poland or Boro Park, Berkeley or his current home in Boulder, Colo. In a new book, The December Project: An Extraordinary Rabbi and a Skeptical Seeker Confront Life’s Greatest Mystery, he tells his life story to veteran journalist and writer Sara Davidson. The book provides a nice interplay between the two, with the rabbi telling his story to the journalist during their meetings every Friday for two years, and the author sharing her own spiritual struggles as well. The book also includes a series of 12 exercises to assist readers with the task of getting a grip on their own mortality, ranging from “Give Thanks” to “Kvetch to God” to finally “Letting Go.”

The December Project is full of the “great questions” that Schachter-Shalomi is famous for asking and descriptions of some of his meditative practices and techniques. The rabbi tells his story and also gives spiritual advice to Davidson as a seeker and devotee. Davidson, in return, balances her own struggles with her career and the death of her mother with the struggles of the once-vital rabbi as he is aging and becoming physically more frail during what he calls his “December years.”

Schachter-Shalomi was born in Poland in 1924, and his family had the wisdom to move to Vienna to work. They fled from there to Belgium in 1938 and then continued from Antwerp to Marseilles and then Spain, Algeria, Morocco, Senegal, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico before finally landing in New York in 1943. Young Zalman encountered some Lubavitchers during his time in Antwerp, and in Marseilles he met Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the man who would become the seventh Lubavitcher Rebbe and one of Schachter-Shalomi’s most important spiritual teachers. Schachter-Shalomi tells Davidson in The December Project: “I found out he’d studied engineering and math at the Sorbonne, and I thought, this guy could show me how to reconcile religion and science.” The reason he was drawn to the future rebbe was not just intellectual; Schachter-Shalomi was also touched by how Schneerson would cough into his fist to cover his tears when speaking about the suffering of the Jewish community and his relatives who couldn’t get out of Poland. Schachter-Shalomi’s own brother Akiva had decided not to go west with the rest of the family; he remained in Oswiecim, Poland, where he and his family were among the first to be gassed in the town the Germans renamed Auschwitz.

Into his early twenties, Schachter-Shalomi was a Lubavitcher, ordained a rabbi by this group, and believed passionately in that way of life. Once he married, he was sent off on shlichut to New Bedford, Mass. While in Massachusetts, he did coursework at Boston University for a Ph.D. in religion with Howard Thurman, an African-American Christian. Of this experience, he told Davidson: “From that time on, I couldn’t see that reading or exchanging ideas with goyim was wrong. It was possible to know them as sincere servants of God, and I could learn from them.” This learning led to a correspondence with the monk and writer Thomas Merton, and a meeting with him at the Abbey of Gethsemani in Bardstown, Ky. Schachter-Shalomi also took LSD with Timothy Leary at an ashram in Massachusetts and recounts going to 770 Eastern Parkway to get the blessing of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who did offer him multiple “l’chaims” for a “good meditation and a good retreat,” according to the account given in The December Project. Schachter-Shalomi recounts what he told Leary after taking LSD: “This is better than schnapps.” When he spoke publicly as a Lubavitcher about these experiences in 1968 in Washington, D.C., the Lubavitchers found him an “embarrassment” and cut their ties with him.

Eventually the rabbi made his way in the liberal Jewish world and began to innovate at Camp Ramah in Connecticut, where he encouraged a do-your-own Judaism from 1961 to 1964 by having campers create their own mezuzot and tallitot, going on 24-hour solo meditation retreats on the outskirts of camp, and encouraging the cooks in the kitchen to turn the fans to the windows so the scent of cooking chicken would waft through the whole camp on erev Shabbat and create a “delightful olfactory association.” In the early ’70s, he started flying to Berkeley, invited by “leaders of the human potential movement to conduct High Holiday services for the counterculture.” One of the rules of free love (by this time he was divorced from his second wife) was that on Friday night, “no one goes home alone.” Schachter-Shalomi adds, “If you weren’t there with a loved one, you loved the one you were with.”

Schachter-Shalomi was one of the founders of the Jewish Renewal movement, which sees itself as a way to practice Judaism that encourages a focus on spiritual practice and a personal relationship with God. Many of those involved in Renewal have come from spiritual searches in other religions, considering themselves JuBu’s (for Jewish Buddhists; see Rodger Kamenetz’s The Jew in the Lotus for an account of this phenomenon that includes Schachter-Shalomi’s meeting with the Dalai Lama) or bogrei hodu (graduates of India) in Hebrew. The website of Aleph, the Alliance for Jewish Renewal, defines the movement as a “joyful, creative, deeply spiritual, and relevant approach to Judaism.” (A picture of Schachter-Shalomi sits in the middle of the website to visually demonstrate his centrality to Renewal.) Much of the movement is not affiliated with other denominations, yet rabbis of all liberal denominations have taken classes at Renewal retreat centers and from Renewal teachers, and many of Schachter-Shalomi’s ideas have thus permeated more mainstream Jewish life.

Now a resident of Boulder, the rabbi has ordained “three generations of his spiritual descendants” and is sought out by “refugees” from the Chabad community who “feel like their minds are in a vise and they want to talk,” since he is known in Chabad as “the one who left.” Davidson writes that “innovations that shocked people in the ’60s were now dispersed across the mainstream. Meditation and yoga were being taught in synagogues of many denominations, youth groups were doing the practices and prayers he’d created at Camp Ramah without knowing where they came from, and people were finding what he’d always wanted them to find in the tradition—spiritual fare.”

The December Project distills a small portion of the spiritual wisdom and teachings about coping with mortality of this rabbi who has spent his life both deepening his ties to the Jewish tradition and innovating outward, bringing the teachings of the Hasidic world to a broader Jewish audience. The intense spirituality that Schachter-Shalomi found in farbrengens and gatherings in the Hasidic world is something he has worked to make accessible to Jews who want an intense spirituality while living in the modern world and to connect to Judaism without being strictly bound to halakhah. He has spent his life telling stories and practices that wouldn’t be known to the average American Jewish audience to give a renewed sense of the possibilities for Jewish life. It is rather nice to read The December Project as a middle-aged adult and to realize how fortunate I was in being around such a passionate spiritual figure as a child, completely by chance. Though of course as Davidson tells her subject, it is possible too that “it’s no accident, that I’m doing this work with you.”

Beth Kissileff is the editor of the anthology Reading Genesis (Continuum, 2016) and the author of the novelQuestioning Return (Mandel Vilar Press, 2016). Visit her online at www.bethkissileff.com.