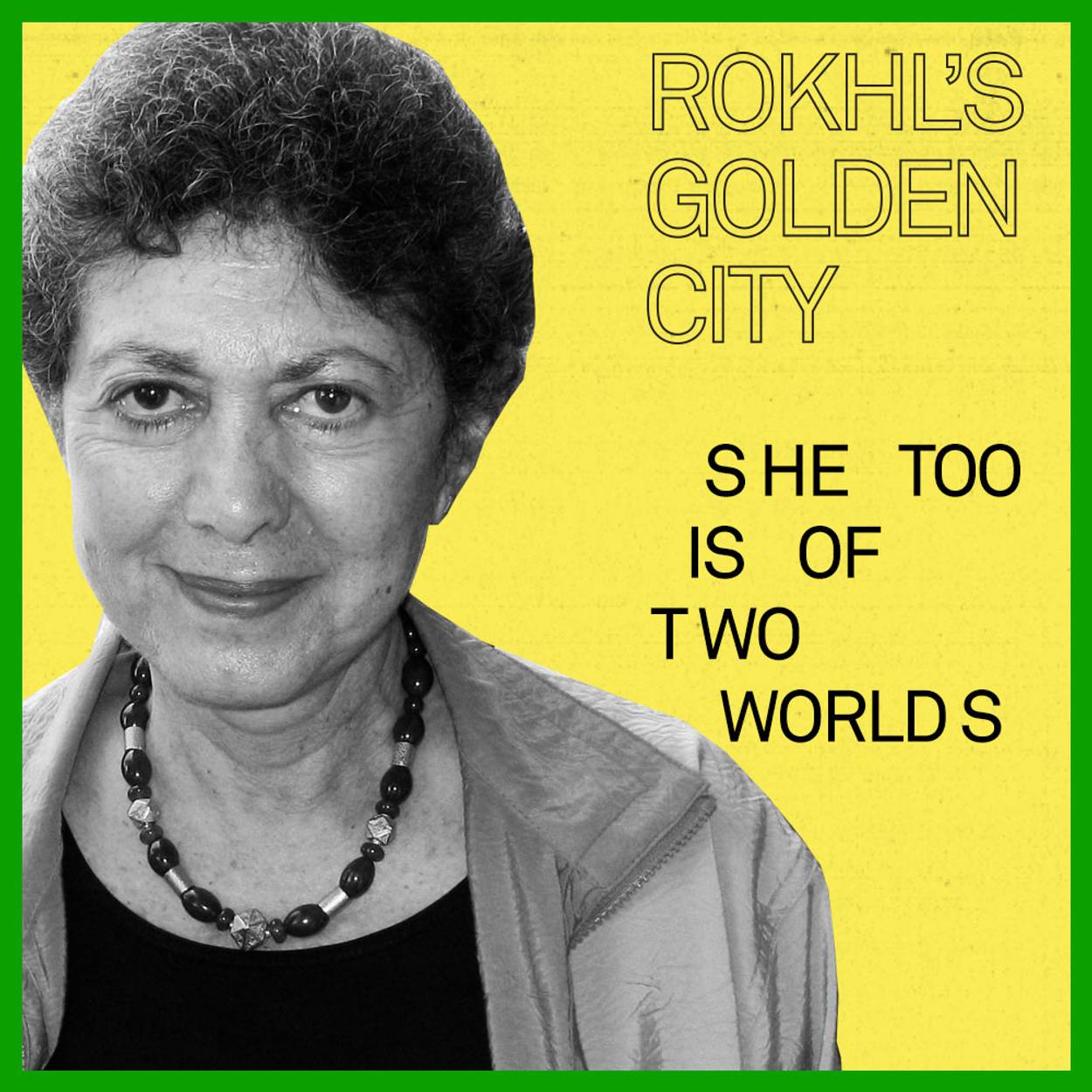

A ‘Naked’ Portrait

Rokhl’s Golden City: Lillian Faderman’s book is an overlooked classic among Jewish women’s memoirs

Not every plague wedding needs a plague. And in America, sometimes a daughter must marry off a mother to save them both.

In Lillian Faderman’s 2003 memoir, Naked in the Promised Land (slated for a reissue this April), 15-year-old Lily despairs for her mother, Mary, an exhausted garment-shop worker. Mary suffers from occasional, terrifying dissociative episodes, the result of a decade of guilt and uncertainty about the family she left behind in Latvia. Mostly, she collapses on her bed, crying out for someone, anyone, to save her from the shop.

It’s 1955 and bright, ambitious Lily dreams of escaping the tension and instability of the furnished room they share in East Los Angeles. Lily’s biological father, Moishe, is a New York cad who denied paternity years before, abandoning Mary and Lily to a life of barely scraping by. And then, one day, above a pickle barrel, Lily spies an ad for a Mr. Yehuda Cohen, Matchmaker. The problem is that nothing will change until her mother gets a husband. Mr. Yehuda Cohen, she decides, is the answer.

A couple months and a few appallingly bad matches later, Mary’s final suitor, Albert, arrives on the scene and quickly proposes marriage. Shortly thereafter, he stops by, accompanied by his brothers. They’re as eager as Lily to see him married off, but feel obligated to read Mary the fine print. “Did he tell you he was in a mental institution for three years?” asks Marvin. Albert was hospitalized while peddling in Veracruz, Mexico. “He had a nervous breakdown,” says the other brother, Jerry. When Albert takes off his hat, he reveals two deep indentations. “They even had to do an operation and open his head.”

It’s an awkward, heartbreaking scene. Albert and Mary don’t love each other. They barely even know each other. What they have in common is that bride and groom both bear the scars of war and dislocation. Neither is likely to marry anyone else. In that, they share much in common with the brides and grooms of the traditional mageyfe khasene (plague wedding). Their “courtship” feels jarringly dark for sunny, 1950s Los Angeles; two unlucky strangers brought together in a $3 transaction.

But the marriage was ultimately a lasting one. It freed Mary from the murderous toil of the shop, and it freed Lillian to leave Los Angeles, and to make history. She ultimately earned a doctorate, blazed a path as a rare female department chair and college administrator, and, along the way, established the field of lesbian history. She even gave her mother and aunt the grandchild they so desperately wanted, with the help of a cockney rabbi as a nanny (seriously, you have to read the book).

But along the way to professional and personal respectability, Faderman’s life zigzags between the margins and the mainstream. To start with, she stumbles into her financial independence through sex work—starting with nude “pinup” modeling at 15 and then paying her way through school by stripping, long before that was a trope. Faderman describes her experience with sex work in a thoughtful, matter-of-fact way that places her far from the anti-sex, anti-pornography attitudes that often seem intertwined with second-wave feminism.

Indeed, what’s most shocking about Naked isn’t her experience in sex work, but how many men regularly expected access to her body, just because she was a woman, and she was there. Mary’s first shidekh match, a man named Jake, molests Lily at the beach, under the guise of teaching her to swim. Then comes Shmuel, a Holocaust survivor, who never goes anywhere without his friend, another survivor named Falix. A truly slimy character, Falix calls her Maydeleh and molests her while Shmuel and Mary are just out of sight. In this aspect, Naked in the Promised Land reminded me of Kate Simon’s Bronx Primitive, another memoir that shattered taboos around naming sexual abuse in Jewish immigrant communities.

Naked in the Promised Land takes place in two overlapping worlds: the Yiddish-speaking realm inhabited by her family and the sunny, seedy, world of greater Los Angeles. In her mother’s world, a white-bearded, old country shadkhen advertises his services in stenciled Yiddish over a pickle barrel. The residents of that realm have one foot in America and one in Europe. Lily is entirely American (or so she thinks), and transforms herself into daring “Lil,” pinup model and sexual adventurer. Hers is multiethnic Los Angeles, with its exciting (and dangerous) landscape of gay bars, burlesque venues, and the burgeoning “adult” industry. It’s a world “Lil” navigates with bravado, to the horror of her mother and aunt. Her mother discovers her nude modeling photos and confronts her: “Is that the way a nice Jewish girl behaves?” To which “Lil” responds, “Nice Jewish girl? How am I Jewish? What do I have to be nice about?”

“Lil” thinks she can simply walk from one world to the other, despite her family’s pleadings. But one of the themes of Naked is Lillian’s slow realization that she, too, is of two worlds. It starts with her teeth, when one helpful friend suggests she get veneers: “How hadn’t I noticed my teeth before? They were hideous hobgoblin teeth pointing every which way, yellow, uneven, crowded like grave markers in an ancient cemetery that I’d seen in a photograph.”

Then it’s her nose. At a photo shoot she accidentally sees a note scribbled in reference to herself, “great figure bad face.” Oof. She convinces her aunt to help fund a nose job, a necessary step, she assures her aunt, toward finding a Jewish husband. As soon as the surgery is done and the swelling down, she’s off to an interview under a new persona, Lil Foster. The agent, a sleazy operator called Mel Kaufman, takes one look at her and asks, “A lantsman [i.e., fellow Jew], huh?” It’s a devastating moment. “I’d gone through my aunt’s hard-earned money and all my own, and still I couldn’t pass.” Lillian’s journey is as much about reconciling to her Jewish identity as it is learning to live as a proud lesbian.

One of the many sob-worthy moments in the book comes when a grown-up Lillian takes off for her fancy professor job in Fresno, setting out by car with her girlfriend Binky. Her aunt Rae rushes down to catch them before they leave: “Bayg arup dos kepele, bend down the little head … She spreads her fingers over my crown and mutters words in Hebrew that I don’t understand as she blesses me. I feel the pressure of her blessing hand all the way up Highway 99.”

Naked tends to be filed under LGBTQ, for obvious reasons, but I think it’s overdue for recognition as a classic of modern Jewish women’s memoirs. In her depiction of a woman’s experience of mental illness, PTSD, sex work, sexual abuse, and non-heteronormative motherhood, it points to all the places where American Jewish history is still waiting to be filled in.

*

It took a year of noodging from my favorite Jewish lesbian librarian to get me to read Naked in the Promised Land and I’m sorry I waited so long. I’m not sure why Faderman was never on my radar, despite reading many of her contemporaries when I was in college.

Conversely, I know exactly why, as a college student, I never read anything by the subject of Nancy Sinkoff’s essential and long overdue new biography, From Left to Right: Lucy S. Dawidowicz, the New York Intellectuals, and the Politics of Jewish History. Though I was obsessed with learning the language, as an undergraduate I didn’t get very far learning about Yiddish. For one thing, I was far more preoccupied with French literature and cinema and feminist theory. It was women like Laura Mulvey, Helene Cixous, and Nelly Kaplan who fascinated me—women who made art and theory and theory about art.

It wasn’t until after college that I became familiar with the work of Lucy Dawidowicz. In that long ago era, before the turn of the last century, resources on Yiddish and Eastern Europe were simply not that easy to come by. If you were a young and excited Yiddishist, for example, Dawidowicz’s From That Time and Place was an easily accessible, must-read account of her time as an aspirant or research trainee at the Vilne YIVO, from 1938-39.

It’s hard to describe the romantic place the aspirantur program occupies for modern Yiddishists. Sinkoff tells us that historian Shimon Dubnow gave the keynote speech to the new aspirantn. YIVO research director Max Weinreich himself guided the aspirantn. Their research topics that year included “Jewish Jokes,” “Budgets of Jewish Families in Vilna,” and “A Lexicon of Jewish Clothing in the First Half of the 19th Century.” I would trade all the Apple and Google internships for a single semester at YIVO in Vilne; I would trade a paid internship with Steve Jobs himself for one month of “Budgets of Jewish Families in Vilna.” But that’s the hold the Vilne YIVO holds on people like me. It was a place so impossibly earnest and righteous and brimming with the absolute best of Jewish Eastern Europe. It is with some degree of awe that I long regarded Dawidowicz, a pilgrim to a holy place no longer extant.

In the biography, Sinkoff writes of her: “A child of the 1930s, when ideological passions ran high and so much was at stake, Dawidowicz, a ‘quasi-survivor,’ in her own words, now considered the security, vitality, and autonomy of Jewish collective existence a nonnegotiable component of her identity.” Reading the biography, I’m reminded that if I’m to allow so much import to her “pilgrimage” to Vilne, I must also weigh the effect its poverty and political insecurity had on her.

Dawidowicz wrote on virtually every topic I care about, often for serious journals like Commentary. Though she taught at Stern College toward the end of her life, she wasn’t an academic. She was a public intellectual, regularly publishing serious journalism about Yiddish and Eastern European history, while employed by one of the most important organizational bodies at play in American Jewish life, the American Jewish Committee. She was, in short, everything I dreamed of becoming. Except that she had landed a million miles away from my own ideological resting place.

I remember one day, it had to be at least 10 years ago, when the American Jewish Committee announced that their archives would be available online. I immediately logged on and began clicking on Dawidowicz’s files with a kind of masochistic glee. I’d long maintained a passionate interest in the world of Yiddish-speaking Communists and knew what awaited me in her files: a treasure trove of memos devoted to their extirpation. I clicked nonetheless. How could I not?

I never quite knew how to approach Dawidowicz’s legacy. She was a bold female voice who rejected the “special pleading” of second-wave feminism. She dedicated herself to Yiddish but rejected it as a basis for Jewish life. She was a frustrating, consternating figure for me, a political thinker who, along with her better known male peers, had journeyed from far left in the 1930s to neoconservative in the 1980s. As I saw it, we had so much, and so little in common. From Left to Right affirms my impression of a woman of fierce intellect and principle, a woman of her many times and places.

LISTEN: Ten years after her own memoir came out, Lillian Faderman published My Mother’s Wars, a “reconstructed memoir” of her mother’s early years in New York. In writing the book, Faderman had to revise some of the history presented in Naked in the Promised Land. She learned, for example, that her mother had arrived in New York much earlier than previously thought. You can hear Tablet Executive Editor Wayne Hoffman interview Faderman about the book here.

ALSO: There’s been some back and forth among my Yiddishist friends about what the Yiddish term should be for “social distancing.” Yiddish literature scholar Miriam Udel suggested gezelshaftlekh dervaytern zikh (literally: social distancing oneself) but I feel like a simple dervaytern zikh is probably good enough. Since that’s what we’re all doing for the time being, I queried my brilliant friends on their favorite online resources for plugging into Ashkenaz fun dervaytns (from afar). Here’s some of the best: Hertz Grosbard was a master of the vort konsert or spoken word recital. This phenomenal website has all 10 of his vinyl albums digitized, along with the texts, so you can read along … Bibliotheque Medem in Paris publishes a wonderful Yiddish newsletter geared toward language learners called "Der Yidisher Tam-Tam.” You can download old issues for free … Yes, it looks like it was designed on a mimeograph machine in 1963, but The World of Yiddish website from the University of Haifa has an incredible selection of full-text Yiddish stories, reference works, and more, including the Yehoyash translation of the Tanakh … The Yiddish Song of the Week blog is crammed full of gems of Yiddish folk song you’ve probably never heard … Can you read music? Do you play an instrument? This is your time to learn some classic Yiddish folk and theater repertoire via sheet music, thanks to the Brown University library … Make sure you “like” the Folksbiene Yiddish Theater Facebook page so you can be notified of all their upcoming live streaming concerts … You could lose a couple days sampling among the 2,000 (!) Yiddish folksongs available through the Max and Frieda Weinstein Archive of YIVO Sound Recordings Ruth Rubin exhibit … If you missed any of YIVO’s amazing public programs, you can start catching up at their YouTube page. There are going to be some exciting announcements regarding online resources from YIVO so make sure you’re following them on social media … Sadly, the Yiddish Artists and Friends Actors’ Club Cultural Seder has been canceled this year, but you can read all about YAFAC and the Hebrew Actors’ Union (the first professional acting union in the United States!) in this new article by Miryem-Khaye Seigel… And finally, if you’ve ever said you wanted to take a YIVO class but didn’t have the time, you just lost your excuse. Offerings include: Discovering Ashkenaz: Jewish Life in Eastern Europe; Folksong, Demons, and the Evil Eye: Folklore of Ashkenaz; and Oh Mama, I’m in Love! The Story of the Yiddish Stage. To register, go here.

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.