A Rebbe for Our Time

A new book reminds us why Menachem Schneerson’s genius for community is more vital today than ever

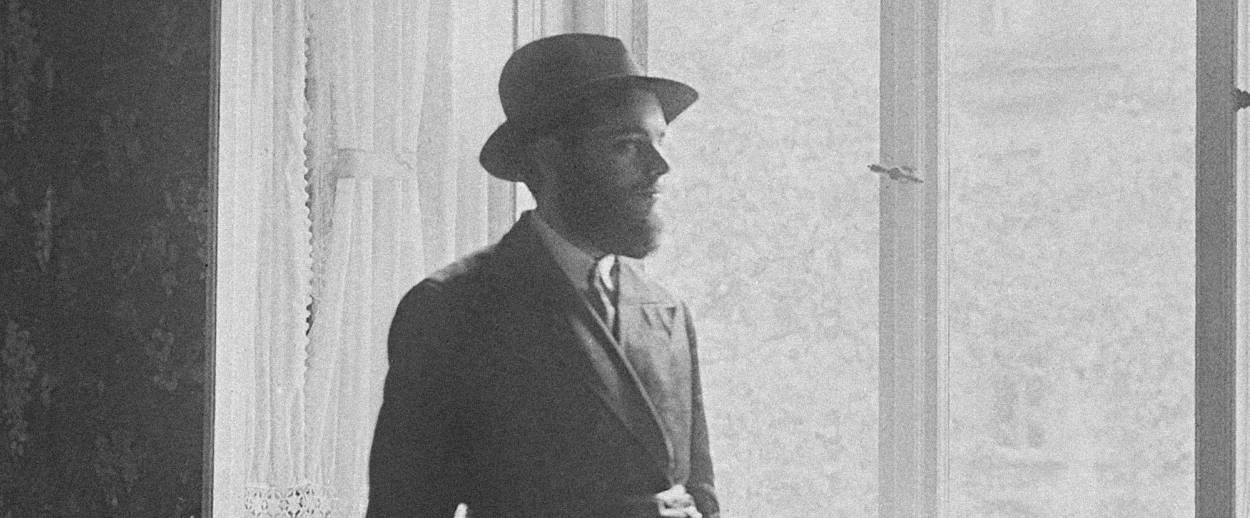

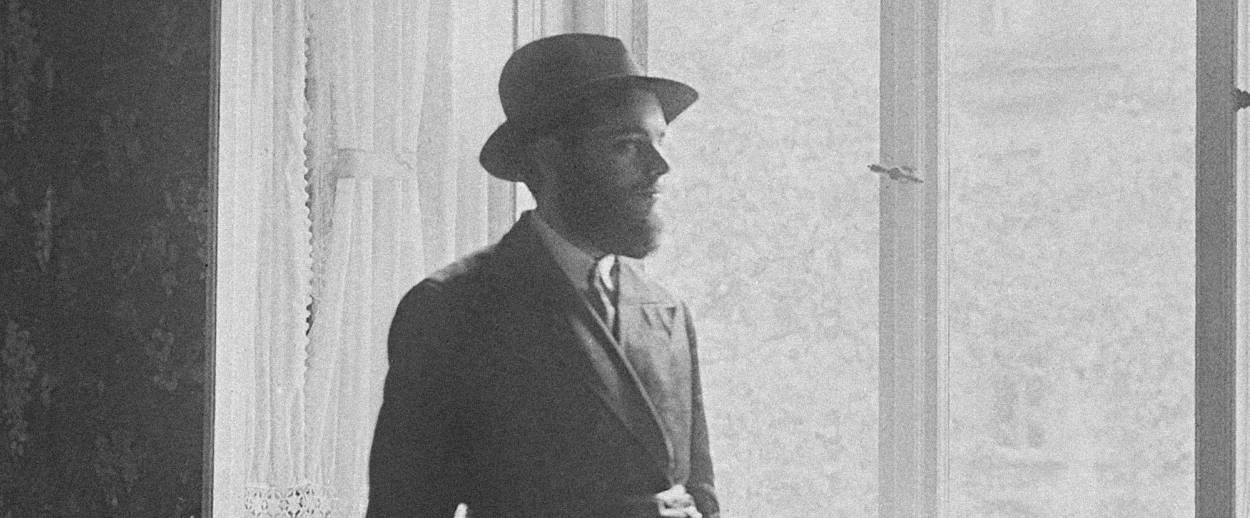

My study, where I spend most of my days reading, moping, and constructing elaborate schemes designed to ward off the faintest threat of productivity, is a purgatory of piled-up objects. It’s the sort of place that would make Marie Kondo weep, especially if she spotted her lovely anti-clutter manifesto jammed in between three identical copies of the Peterson Field Guide to Birds of North America, a small Stonehenge of lifeless iPhones, and official Richard Nixon 1972 campaign memorabilia. None of this stuff is random, though: Each huddled tchotchke is either a souvenir from where I’ve been or a signpost pointing somewhere I’d like to go. And above it all, looking down at me like a bemused elder on an errant boy, is a large black-and-white photograph of the late Lubavitcher Rebbe.

That may seem like a strange choice for an unobservant Jew like me, whose eyes may be watching God but whose mouth is too often stuffed with pork, a believer too timid for the rigors of orthodoxy. But the Rebbe transcends such distinctions—that was his genius. This week, as we commemorate both the 66th anniversary of his ascendancy to the head of the Chabad-Lubavitch court and a gorgeous and exhaustively researched new book documenting his early life, and as we wade in political, cultural, and theological divisions that threaten to undo our commonalities, it’s worth taking a moment to look up to this great teacher.

Like all masters who’ve set out to reveal life’s hidden layers to a species too solipsistic to notice them, the Rebbe, too, delivered his wisdom in subtle ways that are difficult to define. Reviewing a collection of the Rebbe’s letters a few years ago in Haaretz, one of the paper’s cerebral columnists complained that the famed spiritual leader was nothing but a charlatan, an old man fond of sophistry and bereft of intellectual sophistication. That’s an odd claim to make about a polyglot who spoke at least 10 languages, had studied under the quantum physicist Schrödinger in Berlin and was en route to a degree in mathematics from the Sorbonne before World War II intervened, and was a towering scholar who invented a brand new way of studying Rashi and had authored hundreds of volumes. But never mind the credentials: The bigger point the columnist was missing was that the Rebbe’s means of communication were designed to address what he, having narrowly escaped the horrors of the Holocaust, considered to be the key challenge of our time—namely, our ability to strip each other of agency and reduce each other to statistics, or worse. If Socrates spoke in dialogues designed to awaken in his listeners the knowledge they already possessed, and Christ in parables crafted to arouse in his followers the dormant spirit, the Rebbe’s medium was Ahavat Yisroel, or real love of his fellow Jews.

Consider the following, described by Rabbi Joseph Telushkin in his terrific biography of the Rebbe. In June of 1986, the author’s own father, who for decades had been Chabad’s accountant, suffered a serious stroke. The Rebbe’s office called twice daily to ask after the elderly man, but one day it had a curious request: The Rebbe, said his secretary, had a bookkeeping question and asked that his accountant be consulted. Grudgingly, Telushkin posed the question to his father, resentful of the interruption. Then, though, he saw the spark in his father’s eyes and understood immediately what the Rebbe had done.

“Sitting in his Brooklyn office at 770 Eastern Parkway,” Telushkin wrote, “dealing with macro issues confronting Jews and the world, he had the moral imagination to feel the pain of one individual, my father, lying in a hospital bed, partially paralyzed, and wondering if he would ever again be productive. And so the Rebbe asked him a question, and by doing so he reminded my father that he was still needed and could still be of service.”

This moral imagination, the new book about the Rebbe reveals, was inherited from his father, Rabbi Levi Yitzchak Schneerson. Appointed the chief rabbi of Yekatrinoslav, Ukraine’s fourth-largest city, in 1909, he was met with fierce opposition by his fellow Jews, who thought the Hasidic tradition too excitable to accommodate. Schneerson Sr. didn’t waste any time on religious disputations. He didn’t play politics or wage defamatory campaigns or denigrate his opponents. Instead, he invited them to dinner. His prodigious son was 7; by the time the boy became a bar mitzvah six years later, these same detractors were all in attendance, now firm friends. It’s hard to read this account—included in the new book are beautiful reproductions of letters by some of these former adversaries, praising Reb Levi Yitzchak—without thinking about how the father’s tactics influenced the son. Years later, the Rebbe would become known for sending emissaries all around the world and instructing them to erect Chabad houses, where all Jews would always be welcome for a chat and a meal. His own childhood home was the very first such house, and in it, he learned that the personal wasn’t political: Ahavat Yisrael came first and foremost and burned brighter than any disagreement or distinction.

How good are we about following the Rebbe’s example? Myself, not too terrific. The temptation to thunder about the iniquity of others is great—so many misguided souls! so much malice!—and made greater by a torrent of rage-inducing news and roaring social media missives. It’s comforting, in these rocky times, to clamor for the quiet only like-mindedness can bring. It’s tempting to close up your home, not to mention your heart, to all but those who share your convictions and, just as much, your distastes. But the man in the photograph in my study urges me to do better, and the least I can do is try.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.