November 11, 1918: German leaders signed an armistice with U.S., British, and French officials, ending “the war to end all wars.” But U.S. labor union leaders and members had gained ground during the war, and postwar labor militancy was common. The postwar years were big on strikes, Red scares, and Red raids. Corporation owners, politicians, government bureaucrats, conservative preachers, and status quo journalists blamed outside agitators for working-class discontent.

In 1919, seven years after Eve’s arrival, she was tramping around the United States selling anarchist, socialist, communist, and radical labor publications, including Jacob Marinoff’s Der Groyser Kundes. As a traveling saleswoman, Eve joined a group of migratory women who worked their way from New York to San Francisco, making a small living. In 1926, sociologist Nels Anderson reported an increasing number of “hoboettes,” women “bored to death with conventions, anxious to do something new,” “emancipated women,” who resisted “living according to the clock.” Eve Adams was cited as a former “hoboette,” the only time in any document, private or public, that somebody gendered Eve femme.

As a traveling hawker of left periodicals, Eve lived an adventurous, mobile life. But years later, a depressed Eve recalled, “What a price I paid for my courage and perhaps foolishness!” She had underestimated the punishment a noncitizen immigrant could receive for associating with notorious radicals, selling radical periodicals, and publishing a book affirming “lesbian love.”

On July 14, 1919, a Waterbury, Connecticut, police official telephoned Bureau of Investigation agent Warren G. Grimes in New Haven: “Eva Adams” was in town, the earliest dated report of Eve using her new last name. She was “believed to be an agitator,” an organizer for the Industrial Workers of the World, the militant labor organization that U.S. government officials had already taken active, largely successful steps to crush. Agent Grimes and agent J.W.R. Chamberlin that day traveled to Waterbury and searched Eve’s hotel room and confiscated some of her belongings, including “considerable printed literature and subscription blanks to a radical publication.”

The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had, since 1791, prohibited Congress from making any law “abridging the freedom of speech or of the press; or the right of the people ... to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” So Eve’s peddling of radical periodicals should have been protected against surveillance. The Constitution’s Fourth Amendment also provided “the right of the people to be secure in their persons” and “papers,” protected “against unreasonable searches and seizures.” This right to security was extended to all “the people”—formally, at least, including noncitizens like Eve. But Grimes and Chamberlin mentioned no search warrant; they just searched and seized.

In Eve’s room, Grimes and Chamberlin found, took away, and deposited with the Waterbury police a large amount of IWW literature, including membership cards, and some texts in Russian. The agents also took from Eve’s room, and distributed to the Bureau of Investigation, a list of names and addresses found in her suitcase. The list included “Margaret Anderson,” 24 West Sixteenth St., New York City. Just a year earlier, Anderson and her romantic and creative partner, Jane Heap, had begun to publish in their Little Review James Joyce’s sexy, genre-bending, modernist Ulysses.

‘Radicals’ comprised any activist critics of the capitalist system, its elected political representatives, or its unelected businessmen.

A week after government agents broke into Eve’s room, agent Grimes received from the Waterbury police a batch of papers taken from Eve. But Eve had never inquired about her papers and had “slipped away from town,” probably figuring it was useless to protest.

On Aug. 1, 1919, the month after the first known surveillance of Eve, U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer officially created a new “Radical Division” within the Bureau of Investigation to collect data on militant labor organizers, leftists, liberals, pacifists, and other dissenters. A 24-year-old, John Edgar Hoover, was appointed head of the division and created a new “Radical Activities Index.”

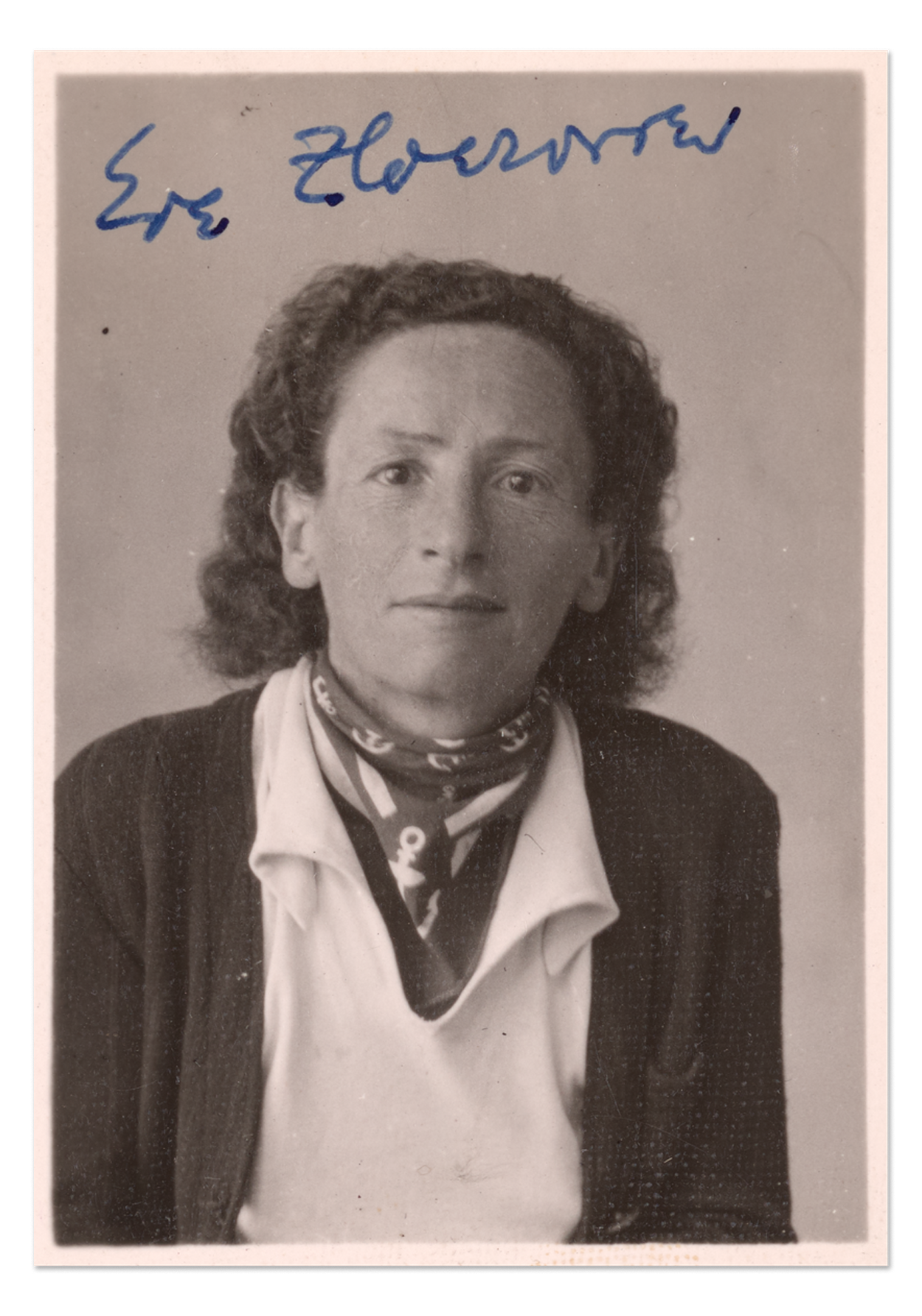

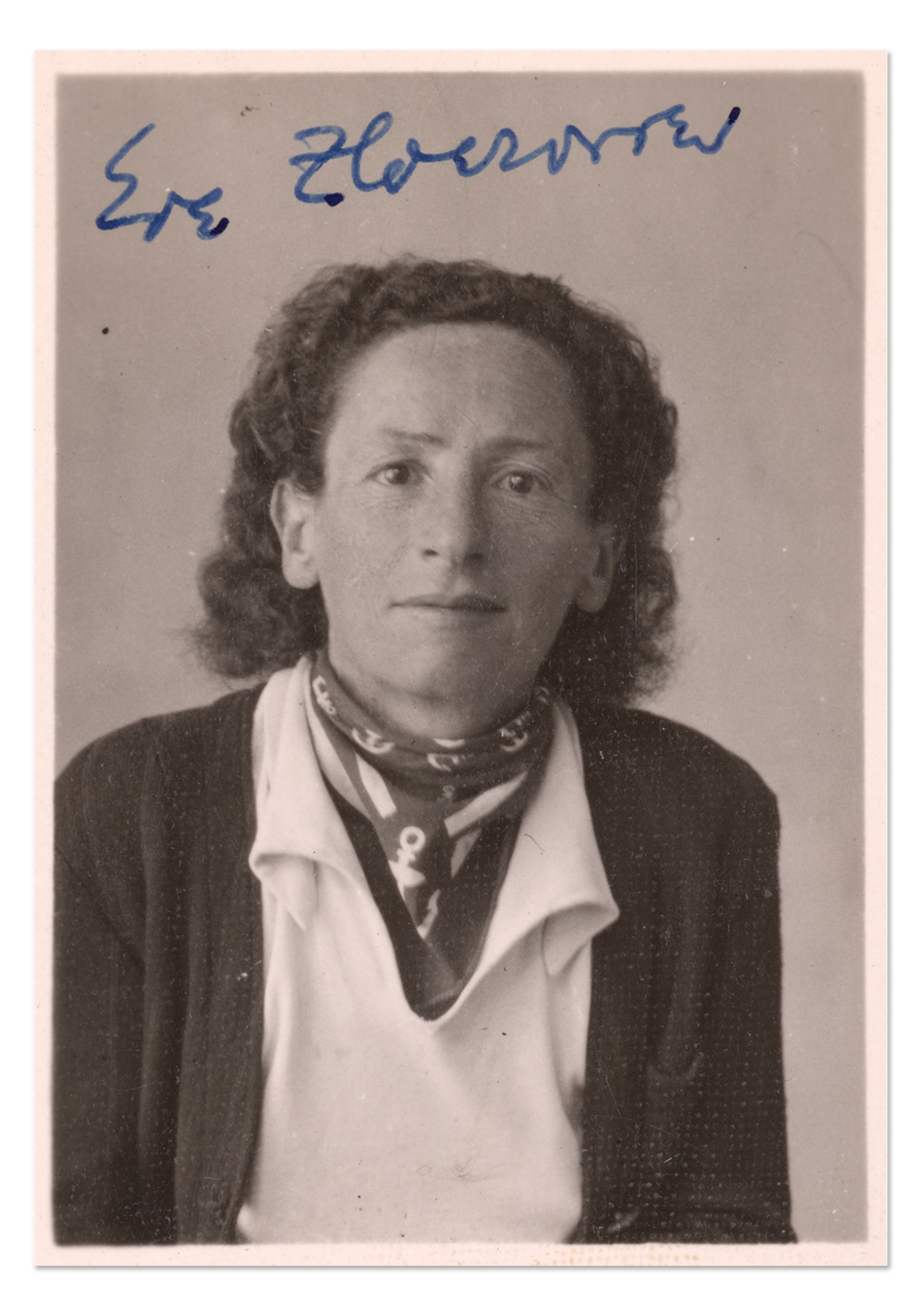

A card referring to U.S. Department of Justice files, probably dating to 1919, was headed “ADAMS, EVA/Alias Eva Zlochevr. Radical activities.” I’m told that Justice Department file 202600-965, to which the card referred, could not be found in the National Archives, but files of the Bureau of Investigation, a division of the Justice Department, do exist, and refer tellingly to Eve.

The Bureau of Investigation’s “Radical Activities” included the acts of IWW members and other militant trade union organizers, anarchists both violent and pacifistic, socialists, and the small, warring, opposed factions of communists. “Radicals” comprised any activist critics of the capitalist system, its elected political representatives, or its unelected businessmen.

Eve’s own radical politics, never explicitly defined by her, probably included an evolving, amorphous mixture of anarchist, socialist, communist, left-libertarian, and militant labor ideas about work, class, and the economy, culture, gender, and sexuality. Eve’s politics are probably best described as left radical.

Eve’s public association with leftist periodicals continued, probably provoking further Bureau of Investigation interest. On Oct. 11, 1919, the Liberator, a socialist “Journal of Revolutionary Progress,” assigned “Eve Adams” to cover a peace conference called by President Wilson in Washington. This is the first public report of Eve Adams using that name, the first to name her a reporter, and the first evidence of her association with the Liberator, the militant journal founded by its editor, Max Eastman, and his feminist journalist sister, Crystal.

As a saleswoman of left periodicals, Chawa Zloczewer certainly needed a name her U.S. customers could pronounce and recall. But her chosen appellation also hinted playfully at her androgynous persona, combining a bit of Eve, a bit of Adam. Eve’s self-naming expressed, in addition, a desire to break with family, tradition, and Poland, to play down her immigrant and Jewish roots, to assimilate and Americanize, like many others. It suggests her desire to define for herself the woman emerging on her exploratory American journey.

“Eve Adams” did not immediately supplant other versions of her name. A spelling of her Polish last name appeared with her new name in publicity for her sales services. In December 1919, the Liberator told its readers that “Eve Zlotchever-Adams” was traveling for the paper and taking subscriptions. “Please give her YOURS when she calls upon you.”

Four months after bureau agents broke into Eve’s hotel room, Attorney General Palmer authorized simultaneous raids on the Union of Russian Workers in 23 U.S. cities. This first big Red scare raid occurred on Nov. 7, 1919, the second anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Over 10,000 suspected radicals were arrested, and often “badly beaten by the police,” as happened in New York City.

The following month, at 5 in the morning on Dec. 21, 1919, Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman were deported to Russia. With them were 184 members of the Union of Russian Workers, 49 other anarchists, eight persons found likely to become public charges, three aliens found guilty of moral turpitude, one procurer, and one undocumented alien. Nobody had warned the deportees or their lawyers, families, friends, or lovers of their immediate expulsion, so Eve and Ben Reitman missed the chance to say goodbye to Goldman and Berkman. But a deportation alert had gone out to a number of reporters and congressmen, who roused themselves in the middle of the night to observe the enforced departures.

Among the deportation viewers was John (now J.) Edgar Hoover, “a slender bundle of high-charged electric wire.” Hoover had made it his crusade to see Goldman banished, and he and the other invited witnesses actually joined the deportees on the tugboat to the ship that would take the exiles to Soviet Russia. A congressman among the deportation voyeurs recalled Goldman’s last words:

Time was when this country had professed to welcome the downtrodden of other lands.

Although the attorney general’s “Palmer Raids” are recalled by that name, the Bureau of Investigation operations were actually efficiently managed by Hoover.

Agents cited her gender-confounding clothes as indications of her nefarious character. A stereotype of the butch, sexually predatory lesbian colored such judgments.

On Jan. 2, 1920, a second series of Palmer Raids resulted in the arrest of 2,585 alleged radicals in 33 U.S. cities. These arrests focused on noncitizen immigrant members of the small, warring Communist Party and Communist Labor Party. On New York’s Ellis Island, arrestees were held in cold, unsanitary, overcrowded cells, and several died. Ellis Island Assistant Commissioner Byron Uhl, who later signed off on Eve’s fate, insisted that no arrestee would be paroled until all were paroled. New York politicians spoke of building a “concentration camp” to hold the Reds.

Eve herself was back in the Bureau of Investigation’s sights on Feb. 11, 1920. That day, agent J. T. Suter, in Washington, D.C., advised agent E. Murray Blanford in the bureau’s San Francisco office:

Eva Adams alias Eva Zlotchevr, who is known to have been a close associate of Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman, is now on a tour of the United States, soliciting subscriptions for various radical magazines. ... She expects ultimately to reach San Francisco, from where she will sail for Poland. She is described as having bright red hair bobbed. She can undoubtedly be located thru the general delivery window at the General Post Office in your city, as she has been receiving mail in that manner in the various cities she has visited.

The notion that Eve was planning to sail for Poland in 1920 was the first rumor of many distributed by government agents—in effect, a U.S. government rumormongering campaign against the radical Eve.

Agent Blanford informed J. Edgar Hoover and the Justice Department on Nov. 9, 1920, that Eve had arrived in San Francisco. Blanford helpfully added, “Any action desired.” Blanford also reported that a “Dr. Charles T. Baylis” had walked into the San Francisco office of the Bureau of Investigation to inform on Eve. Baylis had received a secondhand tip about Eve from “a lady” while all three were on the boat from Portland, Oregon. Baylis had “forgotten” the lady’s name but promised to relay it to the bureau. That lady had, at Baylis’ suggestion, “pretended to be a convert to the Jewess’ radical doctrines.”

The “Jewess” Eve, Baylis said, had declared herself to be an organizer for the “Revolutionists,” a term used then for radicals of all stripes. Eve had been in Butte, Montana, “the headquarters for the Revolutionists in the west.” In Portland, she had just “finished organizing the ‘Revolutionists.’”

In San Francisco, Baylis reported, Eve was expecting to receive names of local “Revolution” leaders, then go on to Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, and eastward. She would then go to England, France, Poland, and “Russia, where she would report to the ‘leaders.’”

She claimed to be working for the love of the cause, but admitted receiving liberal expense money from a headquarters in New York. At Portland, she said, she had received a check for $250 [about $3,300 today].

Eve reportedly boasted that she had used many aliases and had been arrested many times, under many names.

She stated [that] she never carried any “Radical” literature in her baggage for fear of a “raid,” but that it was always sent ahead of her.

How should we understand Eve’s braggadocio as reported by a lady informant to informer Baylis? Is this just another fake fact? Or did Eve perhaps get a bit tipsy on the boat from Portland and exaggerate her radical exploits to a woman she found attractive? That was possible. But more likely, Baylis’ secondhand report was greatly distorted by his blatant prejudice against radicals, Jews, and gender-benders. As Baylis described Eve to the Justice Department, she “has short fuzzy red hair; dresses mannishly and is dirty, greasy and Jewish in appearance.” Baylis, and “a majority of the passengers” on the boat from Portland, considered Eve “a dangerous radical,” he said.

“Dirty” and “greasy” were standard anti-Jewish, anti-immigrant slurs: “I for one won’t stand for a lot of fat Germans an’ greasy Russian Jews tellin’ me how to run my country,” said Billy, the Anglo-Saxon protagonist of Jack London’s 1913 novel The Valley of the Moon. “When you catch me in a socialist meeting,” Billy added, it will only be “when they can talk like white men.”

Baylis was no random citizen informer. In 1919, he was making transcontinental lecture tours on “Making a Better America.” He cast out radicals and immigrants—anyone who didn’t conform to his particular American patriot ideal. Talking to a California Rotary Club, Baylis advocated, “Deport the ‘alien’ red, put the native born traitor in jail, restrict immigration to desirable persons and teach Americanism in the public schools.”

Responding to Baylis’ charges, bureau agent F.W. Kelly, in Butte, Montana, reported that Eve had limited her activities there “to secret conferences with members of the Russian Soviet Metallurgical Bureau.” (Eve’s expertise in metallurgy is nowhere else mentioned.) Eve had also solicited subscriptions to the Liberator, but she had not been “openly active in the dissemination of other radical propaganda.” Butte’s alleged “Revolutionists” were not mentioned.

Eve was “reputed to be a niece of Emma Goldman”—Kelly passed on a false rumor as if it might be fact. The agent also reported that Eve had stayed in Butte with one Albert Keene, “whose wife is an illegitimate offspring of Emma Goldman’s.” A lie. Goldman, the well-researched birth control advocate, had early made a conscious decision not to bear children, and never did. Rumor and unverified fact claims mixed promiscuously in U.S. agents’ reports.

On Dec. 14, 1920, Los Angeles bureau agent E. Kosterlitzky made “a complete search” of Eve’s hotel room and belongings and read her mail, a second violation of her Fourth Amendment rights.

Kosterlitzky reported, “No papers of a compromising nature were found.” Eve was “obtaining subscriptions for radical papers”—Novy Mir and Russky Golos (Soviet papers), Il Martello (an Italian paper), Die Naye Welt and Der Groyser Kundes (Yiddish periodicals), and Good Morning and the Liberator (American socialist papers).

A Los Angeles bureau agent named Sturgis reported on Jan. 14, 1921, that Eve’s activities there consisted of “securing subscriptions to radical publications.” He then commented on Eve’s appearance:

Age: 30; Height: 5′ 2″; Weight: 110; Jewish type; hair cropped, medium dark; Complexion: Medium; Not attractive. Wears nose glasses.

Despite the many references to Eve’s “cropped” hair and gender-bending clothes and demeanor, it’s hard to know how radically she rejected the day’s feminine norms. Eve’s “mannish clothes” were never fully described in any document. She probably wore slacks and rejected frilly blouses when tramping around the country. Agents cited her gender-confounding clothes as indications of her nefarious character. A stereotype of the butch, sexually predatory lesbian colored such judgments.

Agent Sturgis’ assessment of Eve and her appearance was passed on to other bureau offices by agent Fred I. Keepers in Denver. Eve left that city on Jan. 12, 1921, Keepers noted, with a forwarding address in Chicago.

One more U.S. government official had his say about Eve. Matthew C. Smith, a colonel in the U.S. Department of War’s Military Intelligence Division, discussed Eve on Jan. 15, 1921. He had “information from a reliable source that Miss Eva Adams ... a cousin of Emma Goldman and a close relative of Alexander Berkman,” had appeared in Los Angeles. More false claims about Eve’s family links to famous anarchists—passed along this time by a colonel in the Military Intelligence Division’s Negative Branch, dedicated to countering information impairing “military efficiency.”

It “is rumored” that Eve is an organizer of “revolutionist activities” and a representative of Revolution, a New York radical paper, said Colonel Smith. The officer noted pointedly that Eve “is getting most of her subscriptions in the vicinity of Los Angeles from Italians, Mexicans, and Spaniards.”

Smith’s and Baylis’ nativist prejudice contrasted with Eve’s deep feeling for America. Six years later, at Eve’s deportation hearing in 1927, she would plead to remain in the United States: “I learned to love this country with heart and soul and everything about it.” This was not just strategic, an appeal to derail deportation. Eve deeply cherished the freedom she had experienced in the United States and the ideal of freedom Americans professed.

At Eve’s deportation hearing in 1927, she would plead to remain in the United States: ‘I learned to love this country with heart and soul and everything about it.’

Eve added, “The reason I have not become a citizen in all these years, the only one I can give, is through neglect.” The profound, even patriotic love Eve felt for the United States led her to underestimate the danger posed to a radical alien by enemies embedded within the U.S. surveillance state.

Eve’s failure to become a citizen may also have originated with her and her anarchist friends’ rejection of the state as legitimizing institution. Emma Goldman, for example, rejected state-sanctioned marriage, sex, and love. Eve’s failure to become a “naturalized citizen” may have also reflected her religious belief that she and her lesbian desire had been “naturalized” at birth by God.

Five months after Colonel Smith sent his nativist memo, in June 1921, the New York satirical journal Good Morning, edited by the radical leftist artist Art Young, reported:

Eve Adams takes subscriptions to Good Morning. She is now enroute through the north-western states.

In August of the same year, Good Morning published a welcoming story describing a mythologized Eve Adams, reprinted from the Truth, a socialist paper in Duluth, Minnesota:

Eve Adams, the celebrated hiker, who sets out for a seventy-five mile stroll in the morning and winds up with a swim across the English Channel in the evening.

Eve was “on the trail of the artists and students and housewives and farmers and all other workers to give them the inspiration of a lifetime by putting The Liberator and Good Morning and Soviet Russia and Truth into their hands for a year or so.”

Miss Adams has the reputation of having gotten more subscriptions for these publications than any other living Bolshevik in captivity. When you see her you will be sure to subscribe.

“This rebel girl is successful for the one reason that she knows what to select that is worth reading,” the Minnesota paper added.

She is in Duluth just now and while she is there she invites you into the select reading circle of the most advanced intellects of this country.

Years later, Eve fondly recalled the Truth’s heroic account of her as a super saleswoman of leftist periodicals, a larger-than-life people’s heroine. Eve’s drama-filled American life lent itself to mythmaking.

Excerpted from The Daring Life and Dangerous Times of Eve Adams. Jonathan Ned Katz, © 2021. Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.