A Celebration of Liberation

As Juneteenth commemorates emancipation from slavery, the African Methodist Episcopal Church honors its long-standing connection to Black Americans’ struggle for freedom—and the history that has often remained hidden

In Galveston, Texas, the last 250,000 enslaved persons were freed in the United States on June 19, 1865, two years after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Today, in the same place, the African Methodist Episcopal Church—an independent Protestant denomination founded by Black Americans almost half a century before the Civil War—is front and center on Juneteenth, the anniversary of the day that Union General Gordon Granger informed the enslaved persons of Galveston that they were free.

The AME church plays a role in other cities’ observances as well. This weekend in Philadelphia, the birthplace of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Museum of the American Revolution will offer virtual tours of Mother Bethel AME Church for Juneteenth, and the Betsy Ross House will offer a special visit from a historical interpreter of Richard Allen, the denomination’s founder, in observance of the day.

But Galveston takes particular pride in its historic connection to Juneteenth.

“Oh my gosh!” said Sharon Batiste Gillins, a genealogist and chairwoman of Galveston’s annual Juneteenth observance at Reedy Chapel AME church. “This year is phenomenal!”

She describes a project that has “raised the bar” for Juneteenth observances in Galveston, called the Juneteenth Legacy Project, a 5,000-square-foot mural on the side of a building where the Osterman Building was located—the site where General Granger headquartered when he arrived in Galveston in 1865. Gillins said the mural tells the story of the arrival of Africans in America through to Emancipation. It even features an augmented reality component so that viewers can interact with certain elements of the mural through their smartphones.

Gillins said that Reedy Chapel was originally formed in 1848, and it is believed that due to Reedy Chapel’s location near Galveston’s downtown locus, it is one of the places Emancipation was announced, through a sign appearing on the church door.

According to Gillins, contemporaneous newspaper coverage shows that “the very first formal celebration of Emancipation was held at Reedy Chapel AME Church,” on January 1, 1866, to mark the anniversary of the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation. She said it included a march from the Old Galveston County Courthouse to Reedy Chapel, where a program was held inside, with a reading of the Emancipation Proclamation and speeches by U.S. military personnel. The newspaper reports at the time said 800 to 1,000 people took part in the march—no more than about four blocks—in freezing rain. Gillins said the paper announced the march the day before, inviting “colored persons and their friends.” “To me that says this was a diverse group,” she said. “It wasn’t just Black people.”

“Every year we reenact that celebration,” Gillins said of the current Juneteenth celebrations. “We march as a group from the old Galveston Courthouse—we assemble there first, then we read the General Order Number 3, which says all slaves are free, and then we march as a group singing joyfully as we march to Reedy Chapel. And then we have a program inside, where we read the Emancipation Proclamation, we have music and inspirational messages—basically the same thing that happened in 1866.”

This year, like last year, the program will be virtual, due to the novel coronavirus, but the outdoor march is still held.

I asked Gillins if she thinks the discourse and reactions surrounding high-profile deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery last year have raised the profile of Juneteenth in the American consciousness. “That unsettling visual of Mr. Floyd and his demise at the hands of a police officer really ripped the Band-Aid off,” she said. “And it let people in America know these people are not exaggerating. There’s something going on, and we need to know about it. They’ve been saying forever that their lives are being put in danger and that their history has put them in the situation where people believe they don’t matter. Well, it was that visual that made people think, ‘Well, wait, maybe they’re right, and maybe it is true what they’ve been saying.’ And so then, people started re-examining the narratives of history, the believed narratives that we’ve been taught in school.”

That questioning stretched back from the present day to more distant American history, said Gillins: “What is the real story of Emancipation? What really happened? Well, you know, a few people knew that Juneteenth happened here in Galveston, and a few people knew that General Gordon Granger came here with United States troops,” she said. “But nobody ever told us 75% of them were United States colored troops. There was a huge contingency of United States colored troops who came here.” There were 2,000 of them, according to newspaper reports at the time. “Nobody told me that in history,” Gillins said. “I had to go back and dig that up myself.”

That unsettling visual of Mr. Floyd and his demise at the hands of a police officer really ripped the Band-Aid off.

It is just one instance of the omission of Black Americans from their own story. “If you don’t know the contributions that Black people made to building this country,” Gillins said, “then it’s easy to think their lives don’t matter because ‘they never did anything.’ It’s easy to think that. And that’s where we are. The history has been altered. It has been written and controlled by those people who did not want to convey the important role that African Americans have had in building the infrastructure of this country and the culture of this country. And so it has been systematically written out, and so it’s easy to believe, ‘Well, they never did anything, their lives don’t matter.’”

The AME church itself is a crucial part of that overlooked African American history. Early in the United States’ history, white Methodist Episcopal churches were opposed to slavery; this attracted Black congregants, who eventually formed 10% of church membership in 1786. That’s when Richard Allen, a former enslaved person, became an assistant minister at Philadelphia’s majestic red brick St. George’s Methodist Episcopal Church, at the invitation of its pastor. Allen preached an early-morning service and coordinated Black prayer meetings. Black attendance at the church increased, and despite the initially welcoming attitudes at St. George’s, its members of color began to face hostile attitudes from white parishioners. A fissure was growing between church members who favored slavery and the abolitionist faction who remained faithful to John Wesley’s moral objection to the practice. It was a core difference that would lead to the splintering of the denomination in the 1840s.

Allen and his fellow Black parishioners at St. George’s faced opposition from white church leadership to founding a separate Black church, a proposal intended to accommodate the influx of Black worshipers. St. George’s leadership started segregating Black worshippers into assigned seating in a balcony at the back of the church, even forcibly moving them while they were kneeling to pray, a move that prompted Allen to lead a spontaneous walkout during a Sunday morning service.

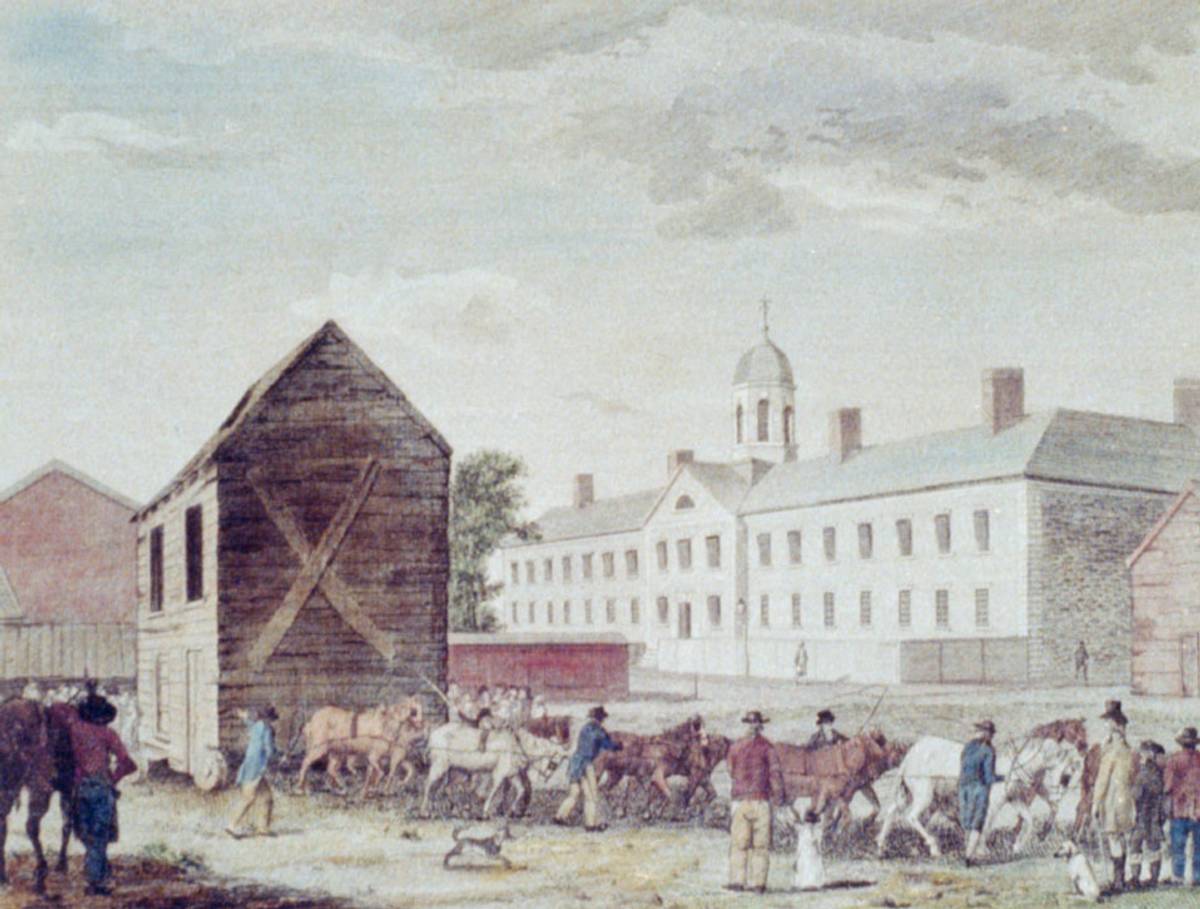

A devout Methodist, Allen went on to found the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in an old blacksmith’s shop in Philadelphia in 1794—a few years after the walkout, which some estimates place in late 1791 or early 1792.

Allen was able to inaugurate a specifically Methodist church for African Americans that was its own denomination in 1816, after a conference of representatives from Black churches across the Mid-Atlantic region agreed to coalesce under the organization of an African Methodist Episcopal Church. These Black Methodists would operate independently, away from the discrimination and the opposition to abolitionism that were emerging in many white Methodist Episcopal churches.

This formal network allowed AME churches to coordinate as stops along the Underground Railroad.

Before the Civil War, the church spread organically outward from its Mid-Atlantic origins, growing into the Northeast and Midwestern United States, with some inroads below the Mason-Dixon line. However, it was after the Civil War, during Reconstruction, when the Union Army let AME clergy function essentially as missionaries, using its clarion cry, “I Seek My Brethren,” to evangelize Southern Blacks who were no longer experiencing slavery in the collapsing Confederacy. By 1880, the AME had grown to 400,000 members.

God blesses every day, God just don’t bless on Sabbath, right?

The oldest AME Church in the South is in Charleston, South Carolina: Emanuel AME Church, which was subjected to repeated racially motivated raids since its founding in 1818, eventually burned down as a result in 1822. Rebuilt after the Civil War, with its current structure dating back to 1891, the church went on to play host to 20th-century civil rights icons such as Booker T. Washington and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Tragically, many Americans know Emanuel from news coverage of the June 2015 racially motivated mass-shooting of nine church members: Clementa Pinckney, Cynthia Hurd, DePayne Middleton-Doctor, Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, Susie Jackson, Myra Thompson, Tywanza Sanders, Ethel Lance, and Daniel Simmons.

A strong centralized organization continues to support both the AME’s secular and spiritual missions. “It’s very organized,” said Rev. Dr. Eraina Ross-Aseme, senior pastor at Bethel AME in Leavenworth, Kansas, who has spent much of her career in rural areas. “It’s traditional. Because we’re Methodists, we carry that core, which is, what we do is methodical. Everything we do, there’s a reason, there’s a plan.” She said this is derived from the New Testament book of First Corinthians, chapter 14, which speaks of “order in church meetings.”

A general conference of about 10,000 elected delegates from the church around the world meets quadrennially to provide uniformity for church membership and the liturgies that govern life in the AME. It’s a faith that consecrates and sacramentalizes the monumental in the form of prayers for the burial of the dead and the marriage ceremony, as well as the mundane, in liturgies for the dedication of a church, of an organ, a hospital, or the laying of a cornerstone. “If someone donates a house, or if we pay off a mortgage, you know, it’s all those types of services,” Ross-Aseme said. “God blesses every day, God just don’t bless on Sabbath, right?”

This theology of methodical access to the divine through created secular realities provides continuity of worship and belief across the denomination and is borne out in the AME’s continued commitment to social justice work. It is, according to Ross-Aseme, the “only denomination that was founded on a social justice principle.”

Examples of this principle abound. Although the AME is sometimes overshadowed in 20th-century civil rights movement lore by institutions such as Ebenezer Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr. actually addressed a conference of the AME in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1964. Rosa Parks was herself a lifelong AME member, serving as a deaconess in the church.

Today the AME sponsors schools—nearly 20 colleges and seminaries spanning the United States and Africa—including Wilberforce University (notable faculty member W.E.B. DuBois). Last month, Wilberforce University President Elfred Anthony Pinkard announced the cancellation of student debt for 2021 graduates. In Tennessee, AME has bishops partnering with universities to teach coding to students in West and South Africa.

Most recently, religious leaders of various denominations gathered at Vernon AME Church in Tulsa, Oklahoma, to observe the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa race massacre and to dedicate the church’s basement wall, which survived the violence, as a place of prayer.

This week, AME churches around the country prepare to observe Juneteenth once again, and it’s no surprise given the church’s constant presence in the American fights for abolition and civil rights. The church has been central to the proliferation of celebrations of Emancipation from the very beginning.

While Ross-Aseme said her church in Kansas doesn’t have anything specific planned for Juneteenth, she said the spirit of the day is inextricable from the spirit of the founding of their denomination. In effect, she said, Juneteenth is “celebrated every Sunday through the liberation of the Gospel.” Because of the church’s history, “We’re reminded that God is for everyone.”

Ross-Aseme drove an hour from her home on short notice to meet me at the present-day Bethel AME, where she has been senior pastor since September 2019. “I get excited when someone wants to learn our denomination,” she said. “We’re the oldest Black denomination in the U.S.”

Everything we do, there’s a reason, there’s a plan.

Bethel AME Church was built in 1861 in Leavenworth, an important hub in the country’s westward expansion and the first city founded in what would later become the State of Kansas. The church’s original Black congregants optimized the conspicuous situation of the tall, stately building on the banks of the Missouri River by shining a lantern from the highest point possible to notify fugitive enslaved persons coming from across the river in Missouri that they had arrived in Kansas, a free state.

At Leavenworth’s Richard Allen Cultural Center & Museum, next door to the present-day church (the original structure collapsed in the 1980s due to structural problems), volunteer tour guide William Wallace described a trap door in the old church’s women’s restroom. It led to what he said was a room about 9 feet by 10 feet, where Bethel AME members would provide shelter and aid to travelers along the Underground Railroad. Artifacts of the original church, salvaged from the wreckage after the collapse, show a community rich in faith: There’s the glass cross that hung over the altar—miraculously unharmed despite the church’s destruction. And there are the heavy wooden altar rails, displaying nicks and gashes, where members would kneel every Sunday for the altar call (the part of the service when they were invited to approach and place their burdens before God in prayer)—or as part of the monthly sharing of communion, which is open to everyone willing to recite the General Confession, a penitential prayer asking for God’s forgiveness, before receiving the symbolic representation of the body of Christ in the forms of grape juice and bread.

The same faith etched in the altar rails in Leavenworth is on display in the various AME churches around the country that are holding Juneteenth celebrations. It’s a faith born of a historic struggle, a faith that has sustained its members and others through the United States’ troubled history of race and that continues to endure and inspire into the 21st century.

Leavenworth’s current Bethel AME church is a no-frills red brick building located on what passes for a busy corner in the sleepy town that bears few traces of its bustling 19th-century heyday. Ross-Aseme gave me a tour of the former parsonage and the kitchen, where they distribute meals to seniors. She took me into the sanctuary, a simple worship space with little ornamentation beyond stained glass windows and an altar decorated with flowers and the green altar cloths associated with the Sundays that fall between important liturgical cycles such as Easter and Christmas, when the altar displays cloths of different symbolic colors, often white.

The first Bethel AME church in Philadelphia was in a blacksmith’s shop, and Richard Allen used an anvil for his pulpit. To this day, the anvil remains in the symbolism of the crest of the AME church, which features a cross and an anvil, as a symbol of strength and endurance. As visitors to the Richard Allen Center prepare to exit through the gift shop, a backwards glance cannot miss the pulpit from the original Bethel AME in Leavenworth. Made by human hands for proclaiming the word of God, it is a reminder that the AME is more than a community of survivors. It is a community of believers.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.