Atheists in Foxholes

As an Army program tries to improve service members’ mental—and spiritual—well-being, nonbelievers see a chance to address bias

“Atheists are in foxholes … and always have been.” That’s the message printed on brochures produced by the Military Association of Atheists and Freethinkers. Founded in 2003, the group today features stories of over 200 active-duty and veteran service members from every branch of the U.S. military (except the newly created Space Force) on its website, and claims a presence “in 20 countries, all 50 states, and over 100 military installations and ships.”

According to MAAF data on denominational affiliations among troops and chaplains, obtained from the Department of Defense via FOIA request, more than 2% of active service members identify as humanist or atheist—which would translate into a total of more than 40,000 soldiers—and an additional 29%, or over 600,000 people, describe their religious affiliation as “uncertain.” Yet, more than 90% of military chaplains are Christian. That’s part of what MAAF president and Army veteran Jason Torpy describes as a bias in favor of evangelical Protestantism among the Army chaplain corps and in the broader Department of Defense professional culture—something his organization was formed to combat.

So it may be surprising that MAAF, which advocates for the conscience rights of nontheist and atheist service members, and supplies them with materials and resources, has been largely supportive (with some qualifications) of a recent Army program intended to improve troops’ physical and mental—and spiritual—well-being. Launched in late 2020, Holistic Health and Fitness, or H2F, boasts evidenced-based approaches to change soldiers’ approaches to physical fitness, mental health, nutrition, sleep, and spirituality.

“Resilience” became a particular buzzword during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, as many soldiers who faced multiple deployments showed serious signs of trauma. In a move that was not without controversy at the time, the Army encouraged spirituality as a part of its campaign to build resilience. Today, 20 years after the start of the Iraq War, most younger soldiers have never seen combat, and although one threat has retreated, another one has emerged, less readily identifiable than an al-Qaida or Taliban fighter. According to the Army’s Center for Initial Military Training, 58,400 soldiers were considered nondeployable in April 2020 (the rough equivalent of 13 brigade combat teams, the units known as the “basic building block” of the Army, usually consisting of around 4,000 soldiers). These were soldiers who were deemed unfit for deployments due to factors like musculoskeletal injuries, inability to pass the Army Physical Fitness Test, mental illness, and sleep disorders. Today, to address these problems, 28 brigade combat teams across the Army have an H2F team dedicated to helping them train, eat, sleep, and work out smarter. This is just the beginning of a 10-year campaign designed to increase the number of deployable soldiers by decreasing the number of musculoskeletal injuries, depression diagnoses, suicide attempts and completions, incidents on the Military Police blotter, and referrals for substance abuse treatment. These are civilian teams, headed by a program director who reports to the active-duty brigade commander, and consisting of up to 36 strength coaches, cognitive performance specialists, and occupational therapists. These teams are integrating with Army chaplains, who are already in brigades, to help soldiers get serious about their spirituality as part of H2F’s stated goal “to build physical lethality and mental toughness to win quickly and return home healthy.” This language comes from the Army’s 2020 field manual on H2F, which describes this muscular, functional spirituality as “spiritual readiness,” which “develops the personal qualities a person needs in times of stress, hardship, and tragedy. These qualities come from religious, philosophical, or human values and form the basis for character, disposition, decision making, and integrity.” This definition applies, the manual notes, to both religious and nonreligious alike.

While military chaplains must be endorsed by a denomination officially recognized by the Department of Defense, they are obligated to minister to all service members in their unit, providing guidance and counseling that is free of proselytizing. If troops are seeking something specific to a faith group other than the chaplain’s own, the chaplain refers them to the right place. That’s the idea, anyway. Torpy said it often works quite differently in practice, and nonreligious service members can be made to feel ignored, marginalized, or denigrated by activities in their unit intended to build spirituality. While there are no secular humanist chaplains in the military, they exist in civilian life at universities and workplaces through organizations like the Humanist Society and the Society for Humanistic Judaism. If, as the Army insists, spirituality is a vital component of overall well-being (and depending on your definition of spirituality, there may be real reason to think it is), secular humanist chaplains could be the answer for a force that is less traditionally religious than in the past. MAAF contends that addressing and confronting the military’s evangelical Christian bias is crucial to H2F’s goal of helping every soldier be all that they can be.

H2F builds on an existing Army program called Comprehensive Soldier Fitness. CSF is an initiative rooted in positive psychology, the theory that the psyche can be fortified against suffering by maximizing optimism and cultivating positive emotions.

In his book The Quick Fix, author Jesse Singal outlines how an uptick in PTSD diagnoses, suicides, murders, and sexual assault among service members and veterans during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan led the Army to seek a psychological prophylactic against trauma for service members headed to war. Around 2008, Army leadership met with director Martin Seligman of the Positive Psychology Center at the University of Pennsylvania, looking for a program to build resilience. The outcome was CSF, which began in 2010 with a $31 million initial contract with Seligman’s center. CSF consisted of mandatory annual self-assessments, online learning modules, and Master Resilience Training, whereby soldiers learned techniques intended to boost their resilience in order to reduce PTSD and ultimately, suicides. MRT was modeled on Seligman’s Penn Resilience Program, an intervention designed to prevent anxiety and depression among high school students using cognitive behavioral therapy. Although Gen. George Casey, chief of staff of the Army when Comprehensive Soldier Fitness was rolled out, said he believed it was “the only way that we are ultimately going to begin to reduce this,” Singal notes that the original Penn Resilience Program was not designed to address suicide or PTSD. “No one associated with it, until Seligman linked up with the Army, appears to have ever claimed it could prevent PTSD or suicide,” Singal writes. “Such an idea wasn’t even on the idea radar of the program’s designers as they built it.” He describes MRT garnering cynicism, as it encouraged soldiers headed into harrowing, life-or-death combat scenarios to find reasons for optimism, a practice known as “hunt the good stuff.”

H2F’s emphases tend to differ from CSF’s, which claims to preempt PTSD diagnoses and suicidality. Where CSF can seem focused on avoidance, H2F seems more comfortable acknowledging the inevitability of hardship and suffering. According to U.S. Army Chaplain (Major) Ryan Wood, tasked with integrating chaplains into H2F’s work, “[H2F] is repackaging it [CSF] into a collaborative effort with other caregivers.” MRT is no longer a stand-alone class simply urging a soldier to hunt the good stuff, rather, he said, it is complemented by “real-time coaching by various specialists that surround these soldiers,” who are “able to hit all these different domains to help them be the best they can be.” Just as a soldier can have a cognitive performance specialist on the gun range with them, helping with visualization techniques before they squeeze the trigger, they can go to a chaplain with “the big overarching metaphysical transcendent questions about the totality of life, and what we’re asking soldiers to do.”

Speaking on the phone, Torpy was less critical of H2F’s spiritual readiness component than might be thought, given his own background. (“I was raised Catholic,” he said, “but that never really stuck.”)

“We want to pick our battles,” Torpy said. “The fact that they call it ‘spirituality’ is just not a fight worth fighting. We can get around that. It’s not our favorite word but you know, whatever, right? As long as we’re not explicitly excluded.”

He concedes that activities that are frequently promoted to enhance wellness are transferable. Reading and meditation can be transliterated into scripture reading and prayer, and community into congregational membership. “Religion succeeds in a lot of ways,” said Torpy. “I mean, some of them are nefarious, but a lot of them are perfectly understandable. Community, ritual, things like that, these are not psychologically surprising things that appeal to people.” The H2F manual also says as much. “While individuals approach spiritual readiness from both non-religious and religious perspectives,” it says, “both categories create similar comparative practices,” giving examples like journaling, meditation, values-based education, service, charity, and community. “Non-religious spiritual traditions may also have certain special days,” it notes.

The H2F handbook for Army chaplains draws heavily on the work of Lisa Miller, a Columbia professor of psychology and education who founded the university’s Spirituality, Mind, Body Institute. It contains a memo by Miller, titled “The Soldier’s Spiritual Core.”

“Science shows that spirituality is a natural capacity in every human being, religious and non-religious,” Miller writes, citing twin studies “that show our spiritual capacity is one-third innate and two-thirds environmentally shaped or ‘socialized.’” Religion is simply the “embrace” of what she says is a “natural spiritual capacity.” According to Miller’s memo, MRI, single gene, and long-term developmental studies have shown that genes and their associated transmitters linked to the production of dopamine and serotonin exist in certain regions of the brain and form circuits, which develop as humans mature. In other words, Miller writes, during puberty, when the brain goes through significant development, adolescents exhibit what she calls “intensified spiritual hunger” triggered by the “biological clock” of puberty. Externally, this takes familiar forms of teenage self-expression as developing adolescents try to answer big questions about who they are, where they fit in, and what everything is for.

This surge typically occurs in late adolescence, when most young people enlist. The Army then becomes a kind of finishing school for helping them deal with challenges. Citing data on university students, the handbook talks about how suicide, fragility, and concerns over disappointment and failure predominate among today’s 18-to-25-year-olds. By developing what Miller calls “a strong spiritual core,” the handbook said soldiers can perceive helpful responses from “transcendent relationships,” acceptance and the ability to find meaning in struggle, and to see life and its component moments as sacred. The result, the handbook maintains, will be the ability to see the interconnectedness of the world around them, and with the bigger picture in mind, to make more mindful decisions as soldiers.

U.S. Army researchers worked to develop a quantitative means of assessing spiritual readiness over a five-year period, the handbook explains. Saying the effort included the input of over 8,000 individuals and incorporated “previously validated questions about spirituality” that they “integrated into a military framework,” the end product was the Spiritual Readiness Assessment (SRA), which is divided into three components, or 3 Core Attributes: Personal Connection with a Higher Power (PCHP), Pursuing Meaning, Purpose, and Value (PMPV), and Service and Sacrifice for the Greater Good (SSGG).

“To make the SRA useful for profiling both theists and nontheists,” the handbook says, “a mechanism was included to allow nontheists to opt out from the PCHP subscale, while still being profiled in two distinct attributes. The SRA provides a good balance of the following properties: It is reliable and metrically sound, it is concise without being narrow, it allows for sensitivity to many belief systems, and it is statistically correlated with many wider wellness traits such as gratitude, quality of life, forgiveness, family commitment, coping, resilience, and adaptive reframing.”

On a scale of 1 to 10, soldiers rate themselves on statements like “I know what my life is about,” “I believe strongly in humanity and the power of people,” and “I have a core set of beliefs, ethics, and values that give my life a sense of meaning and purpose.” To opt out of the Personal Connection with a Higher Power subscale (statements include “I feel God’s love for me” and “Religious beliefs are what really lie behind my whole approach to life”), soldiers fill in a bubble that reads, “The assumptions behind this question aren’t consistent with my world views.” Questions answered in that manner are not factored into the tally of the soldier’s final “spiritual readiness” score. Wood and CIMT Command Chaplain (Lieutenant Colonel) Paul Fritts, speaking over the phone, both said that soldiers can “choose not” to answer these questions, and “absolutely opt out.”

What Torpy wants to avoid with the H2F initiative is the sense that a service member is “unhealthy” due to a lack of belief. The phrase “spiritual readiness” would seem to represent a shift away from the promotion of “spiritual fitness,” which was sine qua non when CSF was the order of the day. The latter phrase was popular in non-DoD-endorsed religious materials and devotionals at the time, creating confusion over just where the official sanction left off and evangelization efforts picked up.

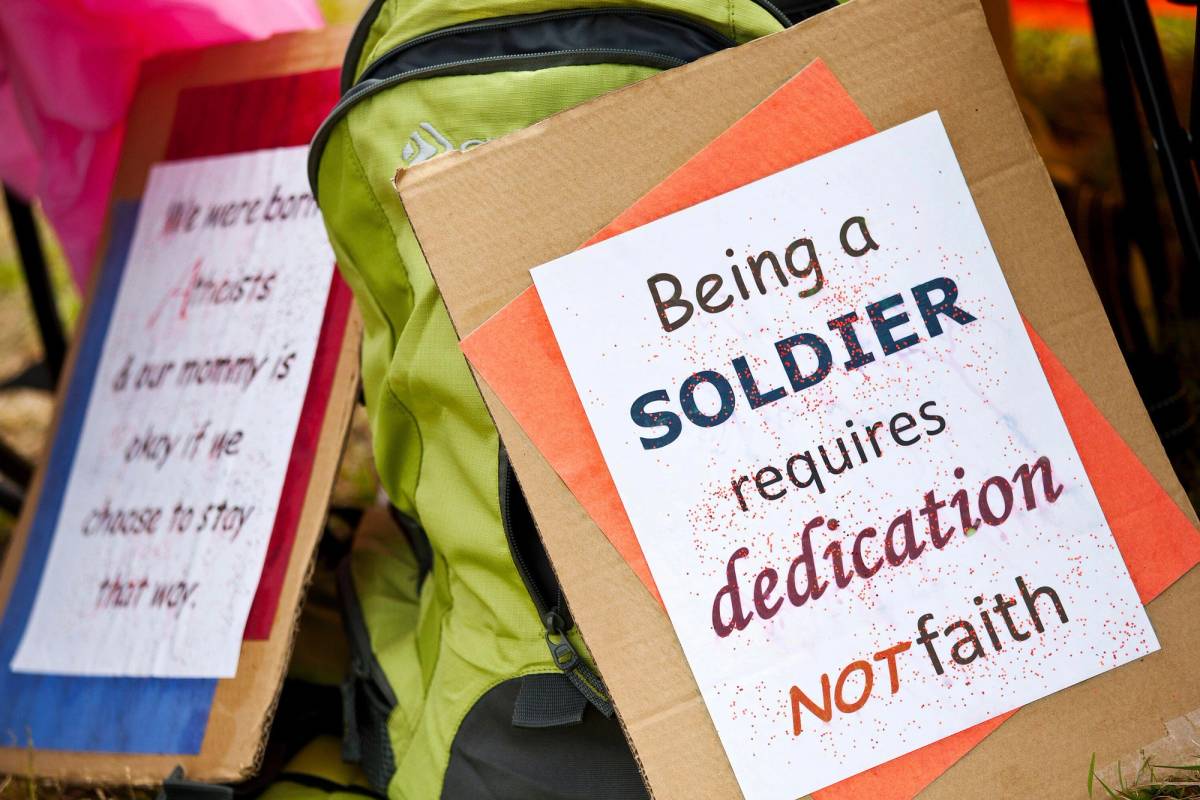

The “Rock the Fort” controversy at Fort Bragg in 2010 was a clear distillation of the tension created by CSF’s use of the phrase “spiritual fitness.” In her 2016 Ph.D. thesis for UNC Chapel Hill’s religious studies department, Shenandoah Nieuwsma provides a detailed account of the events surrounding “Rock the Fort,” a Billy Graham Evangelical Association-sponsored concert at Fort Bragg (home to the U.S. Army’s Special Operations Command; Graham’s grandson, Edward, is a Special Operations’ veteran and COO of evangelical Christian aid organization Samaritan’s Purse). Similar to controversial “spiritual fitness” concerts previously held at other military installations, Rock the Fort featured Christian artists and speakers. The event also featured “Biblical Spiritual Resilience Training,” and was advertised to civilian churches as having an evangelization component. Although the commanding general at the time insisted that Fort Bragg “would be willing and able to provide the same support to comparable events sponsored by similar non-Federal entities,” when a group of atheist soldiers began to organize a corresponding event, “Rock Beyond Belief,” they were given a smaller venue and nothing like the financial and marketing support given to Rock the Fort from the installation’s Religion Support Office, which had been tasked with advertising the religious concert to a 90-mile radius around Fort Bragg. And soldiers from a nonreligious support unit, the 82nd Airborne Division’s Sustainment Brigade, were tasked with setting up for Rock the Fort, which had a budget of over $50,000.

Held in 2012, Rock Beyond Belief ultimately attracted a small crowd of around 1,000 (part of Fort Bragg’s justification for giving it a smaller venue than Rock the Fort, which had a projected attendance of 10,000), Nieuwsma writes. It featured an appearance by Richard Dawkins, who said he “hoped to change the mind of Christians in attendance,” according to Nieuwsma’s account of the event, which she attended, and in addition to bounce houses for kids and standard carnival midway fare, included booths from the Secular Student Alliance and MAAF.

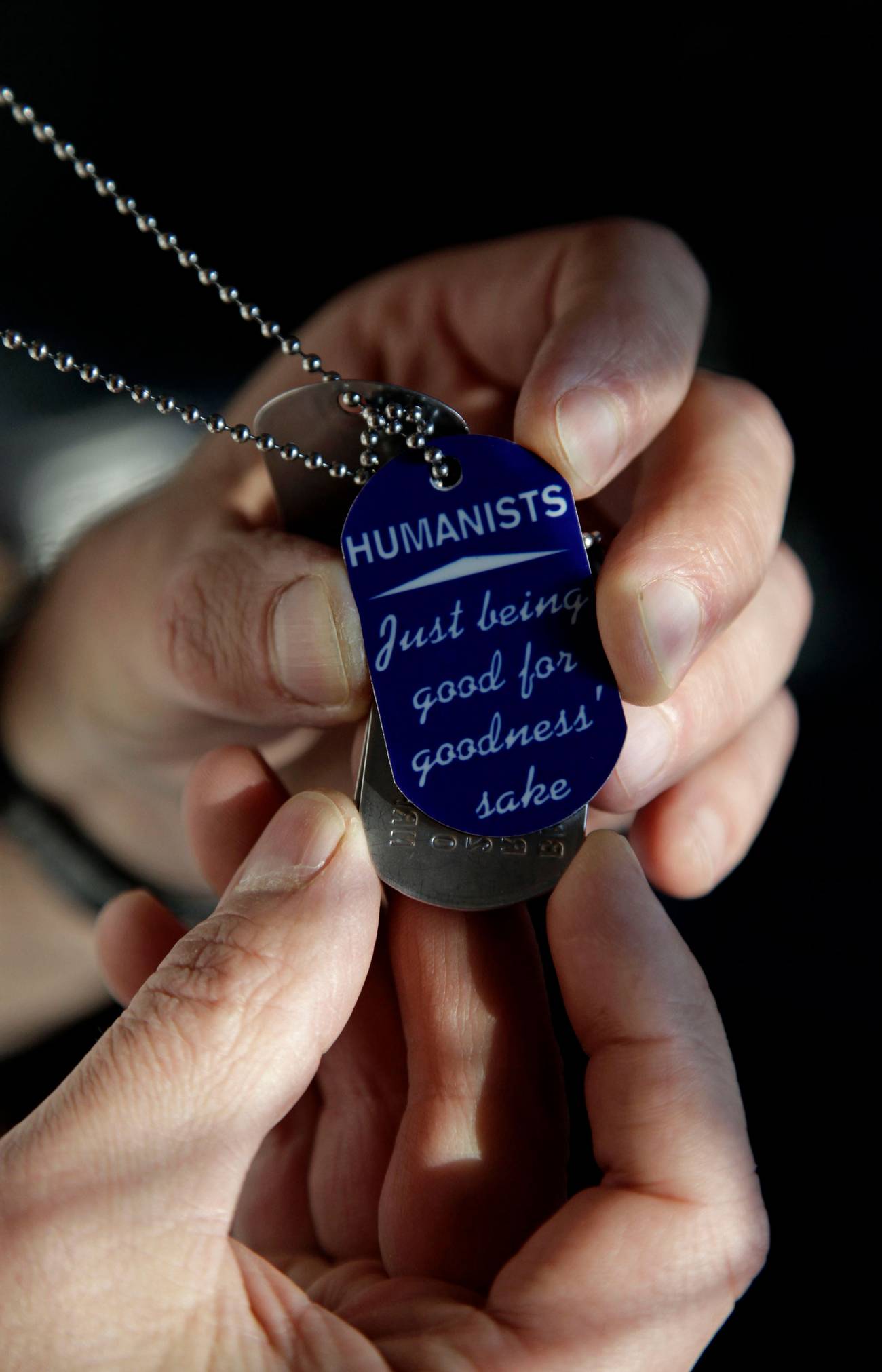

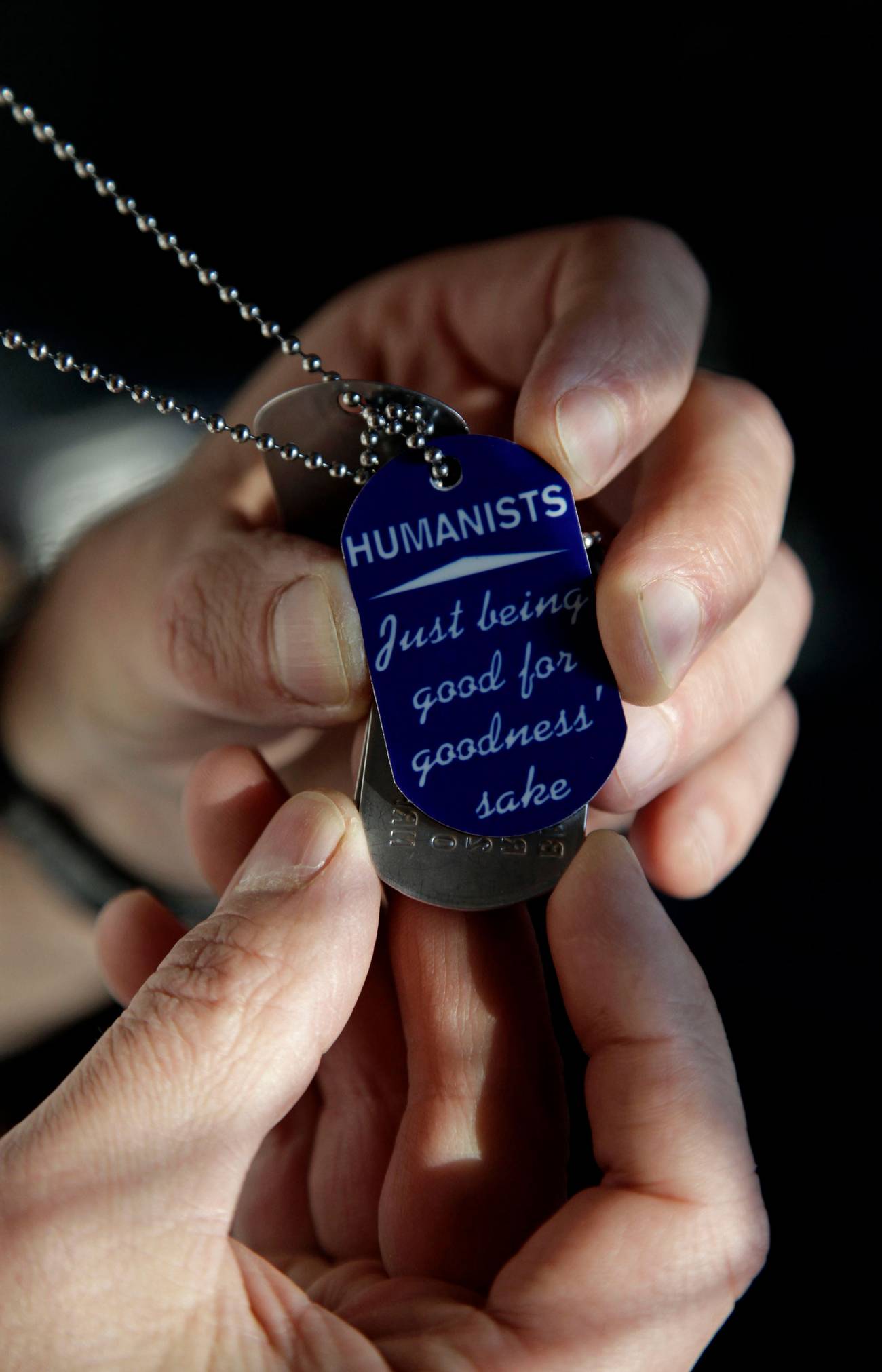

Today, the MAAF brochure that Torpy has available for service members cites athletes like former NFL player Pat Tillman and late baseball great Ted Williams. It also lists heroes like Hans Kasten, a German American military prisoner of war who, during WWII, led his fellow American soldiers to protect Jewish GI’s from being identified by the SS. The language on the brochure states that the term “Atheist” prioritizes beliefs over values, and “humanist” prioritizes values over beliefs, and identifying as a satanist or “Pastafarian” can confuse; “but when we engage, we often find common scientific integrity and humanist grounds.” MAAF membership is intended to help nonbelievers to overcome nondenominational divides to “Build a relationship. Seek common ground. Build a community.”

MAAF also has folding cards defining what humanism means to them: living moral lives based on a reasoned understanding of the world around them, with human flourishing as the highest value. Humanism as they see it seeks the best in the self and helps others realize the best in themselves. To be, as the Army’s recently readopted motto says, all that they can be. On the back of the card, there is contact information to help service members get in touch with their local MAAF representative.

These are the materials Torpy is prepared to provide to any chaplains who come calling, which he said happens “maybe” every couple of weeks.

“It’s very rare that I get a chaplain picking up the phone and saying, hey, I have atheists in my unit, what can MAAF do for us?” Torpy said. “I’m not saying nobody else could do this, but we’re kind of one-stop shop for that sort of thing, we have materials, we have outreach, we have volunteers. Small organization, but we’d get bigger with more outreach. They never call us.”

“Perform and provide” are a “core competency” of chaplains, Wood said. When a chaplain cannot meet a soldier’s spiritual needs due to denominational differences or constraints, they are tasked with providing that soldier with the appropriate alternative.

“We are masters at referring to folks in local areas,” Wood said of his fellow Army chaplains. He said Religious Support Offices at installations usually maintain “lengthy lists” of area churches and ministries, and “meeting-type groups of all flavors and varieties.”

Over 10 years after Rock Beyond Belief took place at Fort Bragg, I called their Religious Support Office to ask if they had a list of spiritual resources off the installation that might include something for atheists. “From my understanding,” said the staff sergeant on the phone, the idea of a religious congregation was antithetical to the idea of what atheists were all about, since they had no beliefs. I told him about MAAF, and Sunday Assembly, which meets about an hour away in Raleigh. Since I was a journalist, he referred me to a public affairs specialist.

It is easy to see how a nontheist soldier might be intimidated in this type of environment; anecdotally, it isn’t unknown for soldiers—even religious ones—to feel like they don’t fit in spiritually. Service member conscience rights’ advocacy nonprofit Military Religious Freedom Foundation founder Mikey Weinstein said in 2010 that many of his group’s clients were Christian service members who had been told they were “not the right kind of Christian.”

Torpy insists that an evangelical Protestant bias persists in the military to the present day. MAAF data indicates that the number of soldiers identifying as nontheistic or humanist may have more than quadrupled between 2009 and 2019, from 0.5% of service members to 2.05%. Following an internal rubric to determine how many chaplains were “evangelistic” (MAAF defines them as “denominations who seem to value the “Great Commission” to convert others and enforce their religious beliefs in their work over the “Great Commandment” to love others), their data showed that they accounted for 69% of military chaplains in 2017. Together with those they deemed “general Christian” (a distinct category from Catholic on their report), nearly 90% of chaplains were Christian, largely Protestant.

“‘I had to hear a prayer once.’ This is not our complaint,” Torpy said. “The issue is light-of-day violations of church-state separation and light-of-day abuses of power.” He said MAAF exists to “provide some sort of shelter from an evangelical regime that you have to kind of opt into to have a military career. And a lot of people, like lots of things in the military, don’t necessarily realize what they’re getting into until they’re into it.” When asked if he knew of any service members who had gotten out of the military because of a perceived a bias against their beliefs, Torpy said, “They don’t like it. Some do. And some stay in and are really kind of not what they could be.”

But this is not the way Fritts, himself a Protestant, envisions his role as an Army chaplain.

“If a soldier who is a secular humanist specifically said, ‘Hey, Chaplain Fritts, can you help me locate a community,’ then you know, that’s my job. That becomes my priority to call around, I would do an internet search, I would find some research on secular humanism, I would see what’s in the area,” he said, “And I would either find something and say, ‘Hey, brother, you know, here’s some phone numbers, here’s some places where you can look on the web to see what I saw and you know, do you need a ride to get there? Do you need me to talk to anybody in your chain of command to give you time to get there?’ Just you know, however we can facilitate and support that soldier’s need. If there’s nothing in the area, then there’s nothing in the area, and so that would necessitate a more in-depth talk to say, ‘OK, what do you need, do you want to start a community, how can I help facilitate that? What do you need by way of resources? Are there particular books do you need? Is there space? Do you need time? Do you need support from the command, do I need to talk to your first sergeant?’ Those kinds of things are what chaplains do to facilitate.”

This is exactly what Torpy said he wants: chaplains connecting with what he calls the “atheists in foxholes” in the unit. “Almost all of them think that you’re their enemy, because you never reach out to them,” he said of chaplains. Like Fritts suggests, Torpy said MAAF advises chaplains to “put something on the schedule and do your job to make it happen” for atheist service members, instead of leaving them to their own devices to plan or coordinate something for themselves in their free time. Typically, he said, chaplains devote a significant amount of their time to servicing Christian denominations, who are often already well-resourced immediately outside the base by civilian churches. Rather, Torpy said, more of their time should be spent “on reaching the population that doesn’t care about them and thinks they don’t want them. Where are the Hindus? Where are the Muslims? Where are the Jews? Where are the atheists in your unit? How can I help you? Why aren’t you coming in to see me?”

What would chaplains put on the schedule, I ask? Something like “Secular Humanist Discussion Group?” “Yeah,” Torpy said. “Something like that. That sounds good. And maybe nobody shows up for a while, I don’t know. But have it there.”

“It’s difficult to you know, kind of be alone in a crowd,” he said. He described getting “prayed at” a lot both on active duty and as a cadet at West Point. “There’s a lot of evangelism and you know, not a whole lot of concern for people who aren’t on board with Jesus.”

Torpy sees the 29.2% of service members with “uncertain” views as neglected within their institutions. “That means chaplains are just letting 30% of people just be like, I don’t even know what their deal is, don’t care if they’re not Christian. That’s what that says to me.”

But it seems that so-called “big Army” may be waking up to the idea that the force of the future may be an army of “nones.” Wood and Fritts recently hosted a “Spiritual Readiness Deep Dive,” one of a series of in-depth online panels about each H2F domain. One of the talks, by Rabbi Elan Babchuck of Clal, the National Center for Jewish Learning and Leadership, is titled, “It’s Complicated: Gen Z, Spirituality, and the Reimagined Role of Faith for Rising Generations.”

“If religion means what the troops want it to mean,” said Torpy, “then those chaplains are going outside their comfort zone to help people in their care, and that’s what chaplaincy’s about.”

The decision on who the Department of Defense says can be a chaplain is made at the highest level: The bodies that may endorse clergy in denominational good standing for the military chaplaincy are in turn determined by leaders from across the service branches on the Armed Forces Chaplains Board. But sometimes the decision goes even higher. In 2018, the Navy was prepared to approve a secular humanist chaplain—the military’s first ever. It didn’t happen. Jason Heap, a member of the Humanist Society, held a master’s in divinity from Texas Christian University, as well as a theological history degree from Oxford, according to the Military Times. Heap had met the first stage of criteria for chaplain recognition, approval by the Navy Chaplain Appointment and Retention Eligibility Advisory Group, when he encountered a hurdle. Sixty-seven lawmakers from both chambers of Congress wrote to Navy leadership in March of that year demanding that the Navy reject Heap’s application. “We are concerned that the Navy is taking steps to expand the chaplain corps beyond its focused purpose,” read the letter from members the House of Representatives (the senators drafted a separate letter). “The chaplaincy was designed to facilitate the exercise of religious belief, not philosophical belief—this is the bright line that the Department of Defense must use in defining the boundaries of the chaplain corps.”

This suspicion of atheists could be a lingering Cold War relic; Nieuwsma and others point out that for much of the 20th century, atheism and communism were frequently linked rhetorically. But Torpy is keen to point out that other faith groups could benefit from secular humanist chaplains in the military.

“If you think about it, a chaplaincy that has a healthy diversity within it has kind of a professional consideration, a professional respect, a professional understanding collectively,” he said. “As an organization, that would really kind of elevate the chaplaincy as a whole.”

As the Army recalibrates to confront the post-global war on terror threat environment—a revanchist (no longer atheistic) Russia, a militarily and economically ascendent China, saber rattling from both North Korea and Iran—they are working with a limited pool of both interested and qualified applicants at home.

“We are seeing increases in anxiety and depression along with the physical challenges,” said Fritts. “A lot of our recruits are overweight, they’re not healthy physically, emotionally, or spiritually. And so H2F is a ‘combined arms attack,’ we are pulling together all of those separate siloed resources.” It is in this environment that the Army has also brought back their old 1980s recruiting slogan: “Be All You Can Be.” With H2F, they aim to help soldiers do just that—physically, mentally, and spiritually.

“When we talk about spirituality for the warfighter,” said Wood, “How does it help you have purpose, value, identity, what does that mean when you’re in the fight physically? What does it mean when you’re needing to be mentally tough to have that? And then when returning home healthy. Spirituality is really of all these other domains the only one that speaks to things like moral injury, spiritual injury, the hideous things that we potentially ask our soldiers to face in combat.”

Torpy is on board “as long as there’s something legitimately for us, which is really a long list of things. Remember,” he said, “stuff that helps us helps everybody.”

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.