Autism’s Growing Problem

As kids with autism become teenagers and adults, fewer and fewer services are available to help them and their families

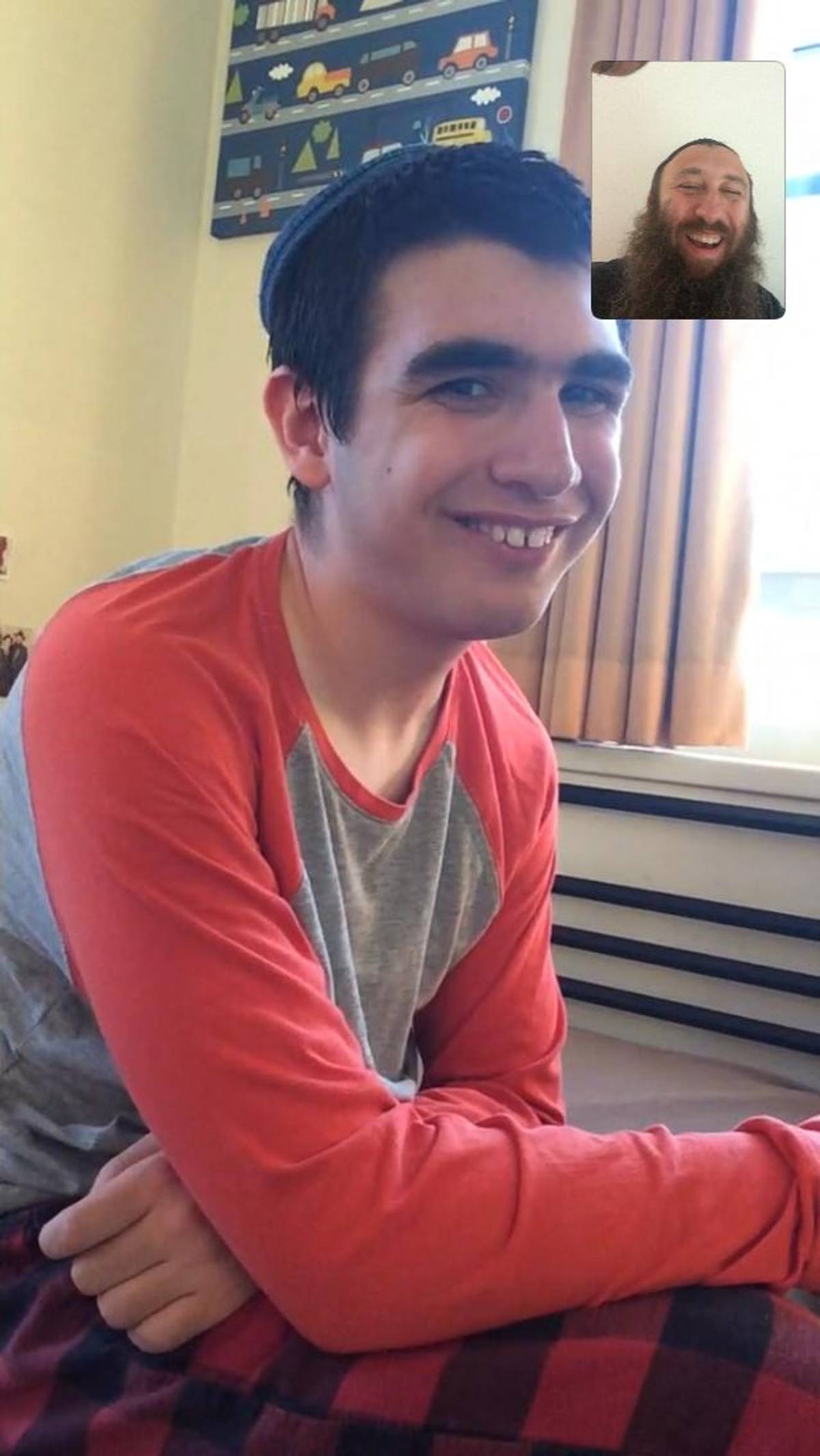

In March 2020, my wife and I dropped our teenage son off at a residential school for kids with autism in Boston. It was the day after Purim––just before the world seemed to grind to a halt––and our race to get there felt a little too much like a thriller movie. Deciding to send our child away for school was hard enough; leaving him there without knowing when we could be together again was agonizing. COVID-19 didn’t help, of course: For the longest time after that day, we could only visit our son masked in the school parking lot (I’ve still never been inside his room). But considering what we’d been through to secure his enrollment, and how clear it was our son was thriving, it all felt worth it. Every time I got in my car to return home after a visit, I felt a surge of gratitude––and a good amount of fear, knowing we’ll face a similar race to get him somewhere safe in just a few short years.

For a long time, I didn’t talk much––if at all––about what was going in my home. I worried that I’d be violating my son’s privacy, or that I’d puncture the image of the happy-go-lucky rabbi I’d cultivated online and in my community. When I open up about our journey with others now, I’m still sensitive to the fact that I am speaking on behalf of my son. But I began sharing because I know the loneliness endemic to parenting a child with autism, and because I thought our experience navigating the world of schools and services could serve as a road map for others. And I keep sharing because while my family’s currently in a happy place, I know all too well that others out there are struggling.

When our sweet, silly, second-oldest child missed developmental milestones as a toddler, we figured he might have some manageable learning disabilities we’d have to deal with as he aged. At the time, we easily managed to secure lots of practical help for him, including occupational, physical, and speech therapy, mostly through the large, impressively comprehensive service providers in our Orthodox community. On occasion, we heard the “A” word, but it was always a whisper, rather than something firm and settled. When he was 7, though, he experienced a major regression, and the A word was no longer a whisper.

Soon after his formal diagnosis, we dove headfirst into the treatment wormhole. We pursued every treatment option we’d so much as heard of, from the holistic to the mainstream medical. We didn’t know anything about how fundamentalist some regimes (and their champions) could be, how much snake oil was out there, or how rigid and dogmatic some providers were: We were in utter survival mode, and tried everything we could.

We tried to put on our best faces and push through. This was especially difficult as we were the communal leaders of a small, beloved synagogue and Chabad house on a college campus in the heart of hipster Brooklyn, so we felt it was our job to show up and serve the cholent wearing smiles, no matter what was happening at home.

Eventually, we came to a place of acceptance (as with most things in our marriage, my wife led the way on that front––I was still the clueless chauffeur for a while). We realized our son didn’t need to be fixed; he wasn’t sick, he just needed help in ways we hadn’t originally anticipated. As long as he was happy and healthy, we would be happy, too. After finally finding a school he loved––his seventh in as many years––we at least felt ready to live our best atypical life.

Soon after his formal diagnosis, we dove headfirst into the treatment wormhole.

But the stability was short lived: A few years later, when our son hit puberty, everything changed in a nanosecond.

Of course, even neurotypical kids find themselves living in a different emotional universe when they’re in the throes of puberty. But when our son, who is selectively mute, was grappling with the rapid and baffling changes to his body, he was also simultaneously struggling to explain the chaos that had infiltrated his once-consistent world. He was sad, happy, and angry all at once, but, unlike a neurotypical kid, he struggled to articulate what was happening to him, and why.

People on the autism spectrum have challenges with communication and social behavior, which can range from mild to severe and can cause difficulties in many areas of life. What appears to be a basic transition to a typical person can cause a neuro-atypical person extreme anxiety. A toddler having a meltdown is one thing, but our son wasn’t so small anymore––he was bigger and stronger than we were. His meltdowns became more pronounced, even, at times, dangerous. He especially didn’t enjoy being in communal settings, even when Daddy was running the show (or maybe especially when Daddy was running the show).

Some Friday nights, when I would have previously been delivering a dvar Torah to a motley crew of college art students and Hasidim, I instead found myself aimlessly wandering the brightly lit aisles of the local Wegman’s, a place my son found relaxing. Over time, I had to find more adventurous and complex ways to soothe him. Our days revolved around creating a calm environment: trips to the aquarium, browsing at Target and or sampling chicken soup at various restaurants in the borough. (Gottlieb’s for the win!)

One day, my son’s school told me I needed to stay within a three-block radius during school hours, in case they couldn’t control him. The administration then started to dance around the idea that he might need a more structured environment. (Later, the principal, who is a friend, told me she often sees these moments coming, but feels uncomfortable addressing them directly with parents, especially as she has few practical alternatives to offer them.) We got the hint and pulled our son.

My wife was the first to realize (again) that our son wanted and deserved more than what he’d had so far. He really needed space, adventure, and a greater sense of independence––when I took him to the park and he sat on the swings, it was obvious to both of us that he was too big. It was around this time that we started to think about sending our then-14-year-old to residential school. But considering residential school and securing a spot are two very different things. All the suitable facilities we looked at had mileslong waiting lists, so we had no choice but to hope that nothing catastrophic would happen before we could secure him a spot.

Out of desperation, we had him admitted to a large medical hospital in the city. Over the course of a week, they performed multiple tests, hoping to pinpoint the cause of his earlier regression, and then told us the results were inconclusive and we could leave. When my wife began to voice her concerns, the young psychiatrist simply walked out of the room, whisking past the enormous bouncer who had been assigned to stand at the door in case our son became a danger to those around him.

Eventually, one meltdown landed him in a pediatric psychiatric ward, a prisonlike setting where we could see our son for only one hour a day. Leaving him there ran counter to all our natural instincts, and the guilt and shame my wife and I felt was overwhelming. But even though we were terrified, our son grew to feel safe there, and even seemed to enjoy the (relative) freedom and autonomy he had. I drove an hour-and-a-half every day to visit him, and the warm, caring staff looked the other way when I stayed beyond the allotted hour to play video games and chat with the teenage residents. I eventually bonded with a number of other parents whose autistic children had also been hospitalized after suffering meltdowns, who constituted a surprisingly significant portion of the inpatient population at this particular facility, by my count as high as 30%.

New York state still doesn’t have a single therapeutic setting for people with autism in crisis.

Despite the fact that it was better than it seemed at first blush, the psych ward was not a suitable long-term placement for my son, or for the other neurodivergent patients there. Though the staff were loving and understanding, none was trained in issues specific to autism. They didn’t have the time, knowledge, or resources to teach these kids life skills or to further their schooling. And yet even as I write this now, New York state still doesn’t have a single therapeutic setting for people with autism in crisis.

The social workers on staff at the hospital would keep our kids there for as long as insurance could pay, fully recognizing that eventually they’d be sent back to the same environment in no better shape than when they’d been admitted. This actually benefited us: Even though our son couldn’t remain there forever, we needed to wait until the Department of Education found him a suitable setting or their legally defined time frame to do so was up, so we could secure our own schooling for him and then file for tuition reimbursement. This is the legal right of every family with a special-needs child, though you’ll still require the patience of a saint to exercise it: You’ll have to fill out endless paperwork, sit through interminable delays, and finally pound on bureaucratic doors to demand that tuition is paid. (Let’s just say autism families, who often take out second and third mortgages or sell property to educate their children, laugh in the face of the Orthodox “tuition crisis.”)

The time following our son’s discharge was difficult. Suddenly, at the moment when we most needed services, they seemed impossible to secure. This was somewhat surprising. Our community has at times lagged behind more liberal denominations of Judaism in terms of sensitivity around speech and representation––though I’ve personally seen huge positive changes in the culture and conversation around disability in every facet of our communal life in recent years––but it has exceled at building institutions that provide practical support for autistic children and their families. When our son was younger, we’d taken advantage of the camps and extracurriculars, and we’d always been so impressed with the quality of the support, both emotional and practical, we’d received. But the service providers are heavily focused on early intervention programs, with little on offer for teenagers and those who require higher levels of support, which means these vulnerable populations are often locked out of programs, ironically deemed too special for special school. Whenever we tried to find somewhere for my son to go, they’d back out upon hearing the word “aggression.”

Being excluded hurts much more when you’ve been told your kid is headed for what amounts to the Disney World of inclusion. The uniformly upbeat marketing content put out by these programs comes from a well-meaning place––the kids holding the bunches of balloons are having fun!––but for families like mine, or disabled individuals themselves, who have been essentially barred from these spaces, it can come across as feel-good sentimentality produced by a reductive, ableist gaze, at the expense of reliable help. (It’s worth noting that presenting people with autism in a one-dimensional way isn’t at all unique to the frum world: Whether they’re cast as a savant, as in Rain Man, or savior, as in the ill-fated Sia movie Music, this trope has a long and icky history.) It can also feel like an implicit command to be positive all the time, even when you are legitimately struggling, and what you really need is to be able to talk freely about the challenges you’re facing.

And while the kids who staff the summer camps and the overnight programs show a dedication and caring far beyond their years––I still get emotional thinking of how one teenage counselor sobbed when he brought my son off the bus at the end of the one summer, when he was still small and docile enough to attend––the truth is, these teenagers are not equipped to handle a crisis. I know a woman whose son got sent home for being violent this past summer after a single day. Another mother I know suggested that these institutions really wanted the kids who occupied a certain autism “sweet spot,” the easy children who could go on the bowling trips and smile for the cameras. (Ironically, too, the lower-support kids risk losing out in this scenario as well, as they often are able to “mask” their symptoms and fly under the radar.)

The process of getting to where we are today was aggravating, isolating, and rife with uncertainty.

When I was told that teachers or counselors couldn’t handle my son, I sometimes wanted to respond that if the staff couldn’t handle the kids, maybe get new staff, not new kids. And yet despite my heated reaction, I recognized that acquiring and retaining staff for what are essentially low-paying, unglamorous jobs is a significant feat (this problem of attrition also transcends the Jewish world—because of a complex web of factors including high levels of stress coupled with often abysmally low pay, special education teachers leave teaching at almost double the rate of general education teachers). I also couldn’t blame the schools, camps, and overnight programs for not being able to offer services that no one could offer. If the entire bureaucratic apparatus of New York state couldn’t figure out how to meet the needs of this population, how could any one institution or community?

It didn’t take long before we had local Hatzolah on speed dial. We were advised by our longtime advocate (who isn’t Jewish) to call them rather than the police, because the latter could potentially harm our son. This was sage advice: Research has shown that people with disabilities including autism are five times more likely to be incarcerated than neurotypical people, and that their interactions with police are “disproportionately” violent. In 2020, police in Salt Lake City shot a 13-year-old boy with autism experiencing a mental health crisis after his mom called 911 for help. And Hatzolah, indeed, proved up to the task: Even though the organization offers no standardized training in handling autistic meltdowns, they always treated my son and our family with extraordinary kindness, stopping just short of dropping off kugel at the hospital to tide us over while we waited for a bed.

After a subsequent hospital admission, we finally learned that a spot had opened up at a school in Boston, a wonderful place that offers instruction in traditional subjects as well as teaching social and life skills. Even as restrictions have eased up a bit, it’s still been hard to see our son less often than we are accustomed to, but he’s developing into a real mensch, and I credit the school with nothing short of saving his life.

The process of getting to where we are today was aggravating, isolating, and rife with uncertainty; in the end, this had less to do with our son’s diagnosis than it did with figuring out how to get the assistance we needed in a world that is largely not set up for kids like him and families like ours. What helped us more than anything was leaning on others who had gone through similar things, who could offer not only practical advice but emotional support.

Soon after my son matriculated at school, my wife and I started shifting away from some of our pastoral duties to providing personal counsel to other autism parents. This year, we founded the Jewish Autism Network, a grassroots, independent, parent-led nonprofit that works to improve the lives of people with autism and their families in the Jewish world and beyond. One of our biggest projects is connecting parents to each other, so that those who have successfully navigated the byzantine world of schooling can support those with less experience. I’ve even started training to become a certified IEP coach, so I can provide more formal advocacy in this area. My wife and I have also been involved in discussions around educational accessibility at high levels of government in New York City, agitating for change on behalf of families whose children have been either effectively denied schooling or who’ve had to shoulder far too much of the cost.

While our family is currently sailing in calm waters, what I see ahead is a storm: the looming housing crisis for autistic adults. Or perhaps “looming” is the wrong word: When I asked one of my friends in our foundation’s network recently if a housing crisis was coming, he responded, “Rabbi, it’s here.” In 2020, 1 in 54 children qualified for a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a 10% increase from the already-high 1 in 59 in 2014. One day in the near future, these kids will grow up, and the higher support population will need somewhere to go.

My son will graduate at 21, and will likely move into a group home, yet currently there are almost no places in suitable facilities. Waiting lists stretch for years, and while individuals sit around hoping for spots, they lose the skills they attained in school. What good are billions of dollars spent on early intervention if we don’t follow through? Parents like me spend years worrying over what will happen to their children when we’re gone (this past year-plus has thrown this problem into starker relief: I know of one adult with autism who lost both parents to COVID-19). And sadly, the lack of availability can sometimes mean people end up in inappropriate settings, where they are isolated, neglected, or even abused.

This crisis is one happening all over the world: In Israel, a group of parents, advocates, and people with autism gathered outside the Knesset in October to protest the lack of vocational opportunities and services for autistic adults. Organizer Emanuel Cohen, whose 22-year-old son is autistic, likened the experience of losing services to being “pushed out of a helicopter.”

People with autism need more invested in their housing, job training, transportation, assistive technology, and independent-living facilities. A variety of options is the key: Though many hold strong opinions about what is the one and only right institutional structure, I believe that for a population this diverse, one size doesn’t fit all. During my networking in this space, I’ve been inspired by the ingenuity I’ve seen, whether it’s in planning smaller “supportive apartments” where residents live in their own units but can take advantage of the communal spaces for socializing, or the numerous kibbutz-style villages in Israel where autistic people can acquire vocational skills that go far beyond the regular grocery-bagging or shelf-stocking. People with autism are an untapped economic resource––especially as we’re reevaluating the intrinsic value of the traditional work environment as a society––and they deserve the opportunity to master skills, earn an income, and reap the self-esteem benefits that come from both.

Of course, there is no way to address the emotional and practical needs of every single autistic individual, because individuals with autism are just that––individuals––and no institution can account for all the variation in human personality and desire. But there are gaping holes in what high-support teens and adults with autism are offered now, holes we are equipped to fill, if only we prioritize doing so. The determination and vision are there, the need is great, the potentials enormous. The only piece missing is the execution. Our communities have been so successful in meeting the needs of small children with autism and their families. Let’s carry that through their whole lives.

With additional reporting from Kelsey Osgood.

Note: Within the autistic community, there are different preferences between the use of person-first language (e.g., “person with autism”) and identity-first language (e.g., “autistic person”). While identity-first language is increasingly embraced among autistic individuals, in order to respect the diversity of voices, I chose to use both terminologies interchangeably in this article.

Rabbi Simcha Weinstein is a bestselling author who was voted New York’s Hippest Rabbi by PBS Channel 13. He chairs the Religious Affairs Committee at Pratt Institute and resides in Brooklyn, New York.