Becoming Historical

In middle-old age, finding a new way to look back at the past offers hope for the future

Philip Roth famously quit writing at 79. After 27 novels, he declared that “the struggle with writing is over,” giving into what he described as the “massacre” of old age. Alice Munro put down her pen at 81. “I don’t have the energy,” she explained, several months before winning a Nobel Prize.

At 79, I am neither as famous as these icons of 20th-century literature—nor as exhausted. Like them, however, I’ve arrived at middle-old age: the stage of life after we make our peace with becoming old, no longer weighed down with the personal and professional responsibilities of middle age, but before we endure the frailties of the oldest-old that turn some aside from active engagement with the world.

Questioning how, if at all, to find a way forward in a career of writing and educational research, I have begun collaborating with younger scholars. Our conversations have proved lively, drawing me away from the dangers of solipsism and into new points of view. I’m brought up short, however, by the deep despair of the next generation of scholars over escalating social injustice around the world and the impermeability of U.S. educational systems to change.

I, too, experienced dark times during my younger years, my memories vivid with newsreels decrying the threats posed by the Cold War in the 1950s, watching the Army-McCarthy hearings on our tiny Admiral TV screen, and practicing for air raids that sent us scurrying from our fourth-floor classroom into the sub-basement of the aging building that housed my elementary school. A decade later, as a young gay man, I knew the violence of police raids on the bars that I frequented on the far west side of Manhattan, and in the 1980s and ’90s, I lived and worked through the worst of the AIDS epidemic that decimated my social world.

Yet today, I have become the hopeful one, the one who turns attention to even the smallest programs that hold the promise of a better future. I find myself the voice of hopefulness amid a chorus of discouragement, turning on its head the stereotype of optimistic, forward-looking younger people and cynical, disappointed older folks. I don’t know when and how I found my voice for a canny, educated hope that heralds the smallest glimmers of light in an otherwise bleak social landscape. Where does hope come from on the cusp of the ninth decade?

Hope is always a slippery if necessary state of mind. For me, it has arrived late in life, as I was detaching from the ambitions of midlife and reattaching to a sense of Jewish belongingness—not because it promised immortality, as some religions do, but because it was a path to a richer, more mindful present. A welcome surprise in the wake of our worried world, the practice of hope links me to people and ideas from other times and places.

My curiosity about social identities began as a Harvard undergraduate when I had the good fortune to study with Erik Erikson, grandfather of contemporary theories of psychosocial development. In 1961, the gray-haired, tweed-jacketed, and German-accented Erikson presided over an experimental freshman seminar series, surrounded by admiring graduate students. Erikson is best known for having posited eight tasks to be addressed at key points across the life span, beginning with Trust vs. Mistrust and ending with Ego Integrity vs. Despair. Although he understood these tasks to be universal, his thinking was capacious in its recognition of cultural differences and of the unique ways that individuals meet these developmental challenges.

I find myself the voice of hopefulness amid a chorus of discouragement, turning on its head the stereotype of optimistic, forward-looking younger people and cynical, disappointed older folks.

At 17, identity seemed to me a personal matter of emergence from the constraints of childhood and family and into adult life. I could not have imagined that a decade later I would have shed my high school identity as a homosexual in hiding and emerged with an uncompromising sense of myself as a gay man and an active participant in proto-clone culture. As feminists were teaching and lived experience was confirming, the personal had become political, private angst transformed into sociopolitical struggle. In retrospect, I see this shift as a first indication that hope might be found as much in the battle as the outcome, the connection with others it fostered as much as in individual achievement.

By contrast, my Jewish history—I was born into a Conservative family and grew up in the heart of New York City’s Reconstructionist world—seemed of little relevance to who I was and the future I dreamed about during young adulthood. Midcentury Judaism was unrelentingly heteronormative, with its emphasis on traditional family and all the accompanying life-cycle events. Gay people were nowhere to be seen, and it was impossible to imagine how I would fit in—indeed, why I would want to be part of an institution that did not acknowledge my existence. I imagine it might have been the same for some single women and those who, either by choice or circumstance, did not have children.

Nor was the progressive, big-tent, believe-what-you-want approach to spirituality of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism any match for my determination to cut a rebellious path in the secular world. Despite a capstone three-month work project on a kibbutz in Israel that marked the end of childhood, I was gone, not to return to Judaism for 50 years.

My gay history taught me a critical lesson about social identity: It can be constructed as well as inherited. In the 1970s, my first life partner and I created events in which our family of choice took precedence over the families and religions into which we were born. I didn’t deny being Jewish, but neither did I find this a place to learn who I was or how I wanted to be. Jewish identity spoke to the past, where I had come from, and especially how my forebears had suffered in the diaspora. Gay identity spoke to the future and the changed world I hope to bring about.

A recent Tablet essay by Danny Schiff puts my Jewish trajectory into historical perspective. Schiff frames the rise and decline of Conservative and Reform synagogues in America as a reflection of the desire of post-WWII Jews to forestall assimilation. Providing a space to support Jewish marriage and family, these synagogues allowed their members to embrace modernity and full participation in the secular state rather than withdraw into separate spaces as many of the Orthodox had. After 1965, with hyperemancipation, or more complete integration into the larger social world, attendance at Conservative and Reform synagogues plummeted. Using a broad brush to paint a devastating critique of Jewish life, Schiff claims that these synagogues did not provide a systematic approach to Judaism that would lead to durable commitments and practices. People joined synagogues more by “default than by devotion.”

While Schiff’s thesis does not always map directly onto my own experience, when I put his essay down and stopped arguing with it, I realized that something had shifted within me, and a weight I hadn’t known was there had suddenly lifted. It’s not that the story of Jewish life in America contained good news about the past, but rather that I found comfort in understanding my personal experience—my early battles over attending synagogue during the Yamim Noraim and the alienation I experienced at life-cycle events—in a larger context, as reflections of bigger social currents. Schiff authorizes me to read midcentury heteronormativity as part of the Jewish approach, wrong-headed as it may have been, to succeeding in post-WWII America.

I identify the shift within me as a move toward hope, the kind specifically that comes from “feeling historical,” a phrase that I first encountered in Christopher Nealon’s description of the struggle of gay people in the 20th century to establish meaningful identities. Then, leaving behind a sense of isolation and pathology, gay people began to recognize connection and community with others like themselves on the margins. Today, when I step back and place my personal story in the context of broader social narratives, I know I am becoming historical.

In feeling historical, I reject the Scylla of defensiveness when we wield history as rationale or excuses for what we did or didn’t do, and the Charybdis of nostalgia when we look through rose-tinted glasses. This would be to celebrate my rich Jewish home life, including intense family debates about Reconstructionist thought, and to ignore the way that gender-inflected discrimination characterized our family arrangements. Feeling historical, I try to navigate a more even-keeled trip through the past that docks at what Erik Erikson termed “ego integrity.”

Erikson describes the final life challenge as finding a sense of ego integrity rather than succumbing to despair. Erikson writes that ego integrity is “the acceptance of one’s one and only life cycle as something that had to be” and as “a sense of coherence and wholeness.” It allows us to recognize that we have had a life well-lived and to jettison regrets and self-recriminations.

Feeling historical brings a heightened attention to the larger currents of human events that frame our lives and complements Erikson’s psychosocial perspective. Looking back, I see that I was not as in control as my younger self imagined, nor as special as my middle-class privilege often led me to believe. Not in control, not special, and yet hopeful when I see the opportunities open to young queer people that I could not even have imagined in my 20s, 30s, and 40s. Hopeful, too, because when I married David, my second life partner, and had to put down roots in a new city, I was able to find a thriving LGBTQ+ welcoming synagogue that asked no questions about spiritual matters. Several years later, when I was ready to ask these questions, I was able to move to another small, progressive community that also embraced its LGBTQ+ members and spoke more directly to the philosophical issues that engaged me as I entered my 70s.

Now, in middle-old age, I am mindful of the instruction that I received from my father, who lived into his 90s and managed to sustain hope in the face of a cascading and ever more debilitating series of medical crises. After each event, I observed him recalibrate his expectations and set goals that he considered unacceptable just a short time before. In those years, while losing mobility because of severe spinal stenosis, he daily practiced walking from one end of his apartment to another. Then, rejecting and at the last minute agreeing to surgery for esophageal cancer that prevented him from swallowing food, he accepted the challenge of being fed through a tube in his stomach.

My father exercised a modulated hope that allowed him to look at the present and toward the future without becoming overwhelmed by what he saw. Modulated hope, in contrast to blind hope that defends against remembering difficult personal and social histories and projects unrealizable worlds, uncouples the future from grand schemes of progress and places it in the proximate present.

In recent conversations with my younger colleagues, I have become more explicit in pointing out that we have survived dark times before and that there is comfort in the long view, with allowing ourselves to feel historical. This isn’t to eschew looking at devastating inequities, but it is to temper more ambitious ideas about the future and to insist on a balance between our commitments to big picture changes with engagement on smaller, local projects that provide immediate, sustaining satisfactions that are essential to moving forward.

I am only too aware that many are far from hopeful in middle-old age, undone by social injustices or marked by personal tragedy. In particular, my African American and transgender colleagues have good reason to mistrust the contemporary world. They risk potential violence in their daily lives that I do not.

Feeling historical is not a fix for this broken world. But I embrace it in the spirit of the Misheberach, the prayer for the sick, when we seek healing, as much as medical cure. As I have, I hope that my younger colleagues can realize that a sense of wholeness, of ego integrity, is buttressed when we modulate our personal ambitions with feeling historical in the face of the ineluctable challenges of aging and a society run amok. I hope to convey as well the value of allowing an educated hope to be our guide in imagining the future otherwise.

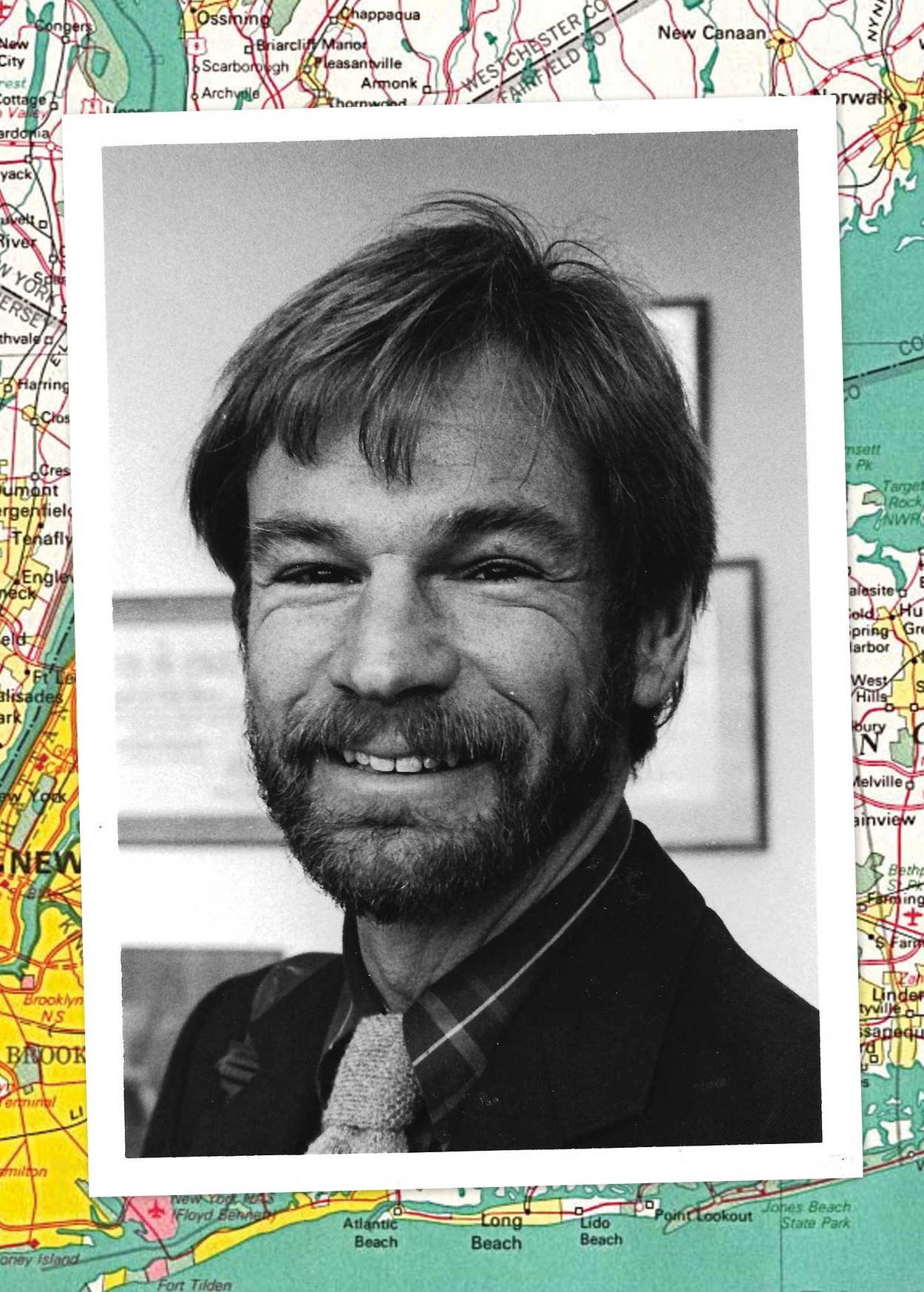

Jonathan Silin is the author of four books including Early Childhood, Aging and the Life Cycle: Mapping Common Ground. He is a fellow at the Mark S. Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies, University of Toronto, and was the life partner of the American photographer Robert Giard. He lives in Toronto and Amagansett, New York, with his partner, David Townsend.