Behind the Blood Ban

Donor discrimination has deep roots in antisemitism

The Austrian government announced last month that the country would soon put an end to its lifetime ban on blood donations from gay and bisexual men, joining the U.K., Israel, Greece, France, and a slew of other countries that recently eliminated their de facto “gay blood bans” under pressure from LGBTQ+ activist groups and COVID-19 strains on national blood supplies.

But in the United States, the ban remains in effect as the pandemic rages on.

Starting in 1982, gay and bisexual men were barred for life from giving blood. But in 2015, trailing the passage of the Marriage Equality Act, the FDA reduced the ban on MSM—men who have sex with men—to one year, meaning a male donor had to abstain from having sex with men for one year before he could donate blood. Blood donations in the U.S. regularly met demand, even with the ban.

Then came the coronavirus, and like many other sectors of the health care system, transfusion centers and blood banks struggled to cope with unprecedented shortages. In response, the FDA released an emergency recommendation relaxing the MSM ban to three months, in hopes of encouraging more donors. The abbreviated ban went into effect in June 2020, but to no avail. Facing an ongoing blood shortage, activists, lawmakers and medical professionals in 2022 have urged the FDA to scale back the ban even further.

The blood ban was born in the early years of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in the U.S. But to fully understand how policies like this one came to be, one must look to a more distant time and place.

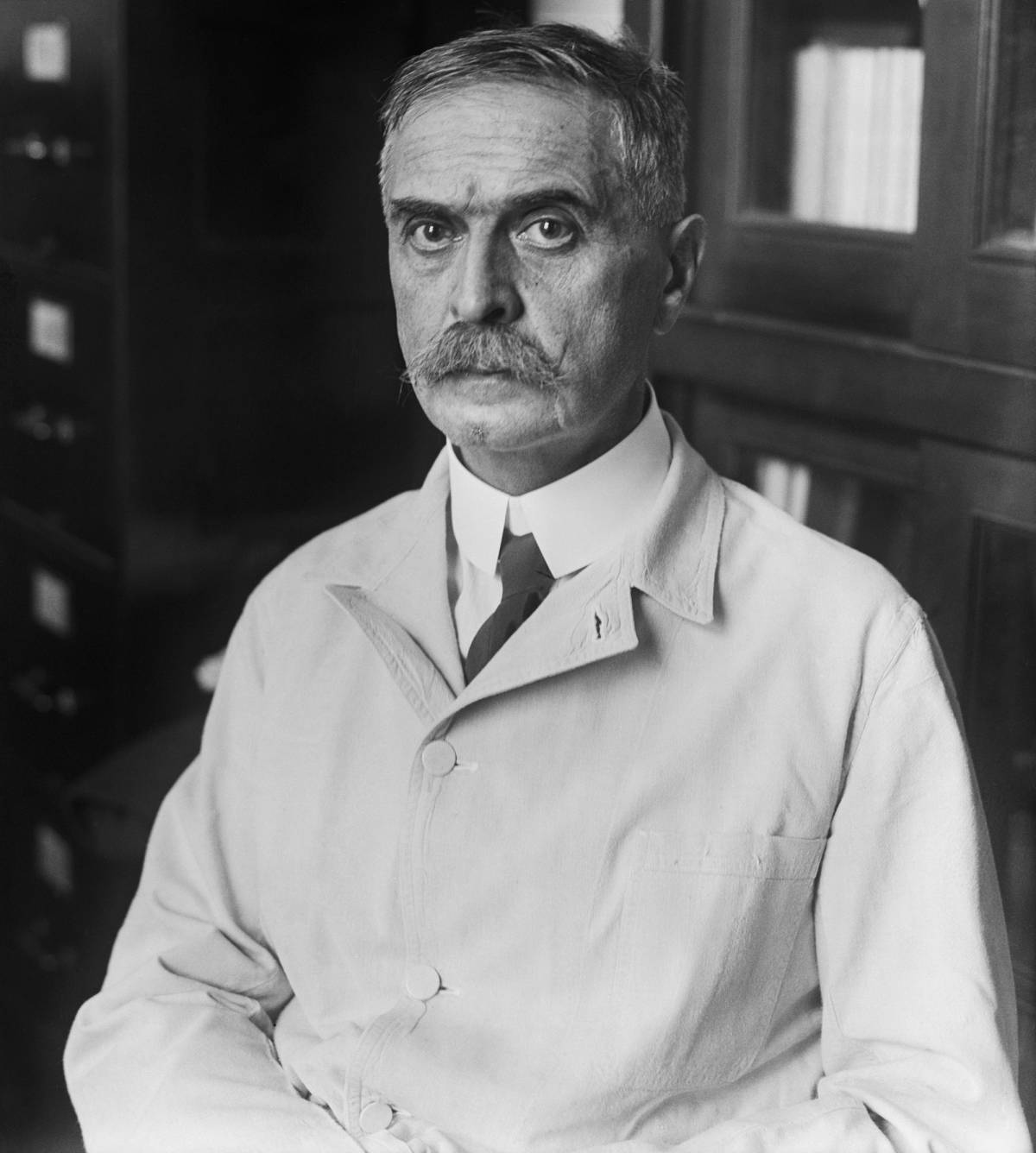

The story begins in 1900, when Karl Landsteiner, an Austrian Jew who converted to Catholicism to evade persecution, made safe blood transfusions possible through his discovery of blood types. Prior to this incredible breakthrough, blood compatibility was overlooked in medicine and transfusions often ended in death.

It’s no coincidence that Landsteiner made this discovery. In countries like Austria and Germany at this time, antisemitism helps explain the disproportionate role of Jews in the development of serology, the scientific study of blood serum. In her book In Search of Aryan Blood, Rachel Boaz writes that specializing in one area of clinical medicine gave Jewish doctors the opportunity to enter into private practice, whereas general research work could only lead to a university position, where Jews were restricted by conservative leadership.

At the same time as Landsteiner’s world-changing discovery, a new book written by a young doctor was selling out all over Germany. The Operated Jew chronicles the efforts of a German Jew, Itzig Faitel Stern, on a quest to shed his Jewishness. And what’s his plan, exactly? “To buy some Chreesten blud!” Stern says. (This very specific spelling comes from an English translation of the book.) After undergoing extensive plastic surgery to remove his stereotypically Jewish features, he attempts to pay six Germans for a liter of their blood each. The German donors decline when they learn their blood would be given to a Jew.

Stern’s pursuit of German blood to remove his Jewishness exemplified the idea that identity is rooted in physical blood. And though the burgeoning serology field should have shed new light on the matter, it only further fueled the racial propaganda of the late 19th century. “Scientific” antisemitism took center stage, thanks to a strong foundation of Christian antisemitism and the popular belief that medicine was independent from politics, religion, and ethics, and therefore a fairer basis for discrimination.

Another book titled The Sin Against the Blood, by infamous Nazi Artur Dinter, hit the presses in 1917 as Germany’s WWI-induced blood crisis soared. The book follows an Aryan German man and woman whose children are born with stereotypically Jewish features. It is uncovered that the woman, although Aryan-presenting, has some Jewish ancestry, and when her husband leaves her for a more suitable partner, his new offspring again appears Jewish. The pseudoscience of the novel pushes the now-laughable notion that, after having sex with one Jewish person, this Aryan man’s blood is forever tainted by the blood of a Jew—that Jewishness is a sexually transmitted disease that should be avoided at all costs.

The Sin Against the Blood went on to sell a million copies in Germany between WWI and WWII, and underpinned the racial theories that spread across Europe and garnered support for the Nazi party.

As the WWI death toll rose in Germany, the national birth rate dropped and syphilis—which caused stillbirths and birth defects—ravaged the population. Racial theorists panicked, predicting a deterioration of the Aryan race. To prevent Jews and other ethnic minorities from tainting the Aryan gene pool, blood screenings became commonplace.

The first “Jewish blood ban” case was documented in 1935 when Hans Serelman, a German Jewish physician, donated his own blood to save the life of a German soldier rushed to a nearby Jewish hospital where Serelman worked. German physicians reported Serelman to the Gestapo for injecting Jewish blood into a German patient, and Serelman was charged with the crime of “race defilement” and sent to a concentration camp. In the trial, Serelman admitted to previously transfusing his own blood to save the lives of other patients when no other blood was available. In every instance, Serelman’s blood recipients survived because of his scientifically safe but socially risky actions.

Blood transfusions and sexual contact between Germans and Jews became outlawed in Germany, and soon after, Austrian transfusion sites began using only blood certified as “gentile” for transfusions performed on “German-blooded” patients. These very policies inspired the Nazi party to create the Mischling Test used to determine whether a person was deemed a “Jew” or a “Mischling” (mixed-blood) in Nazi Germany, and therefore sent to a concentration camp.

Our science has advanced to the point that the blood ban is no longer about thwarting certain viruses; it’s about thwarting certain people.

Blood discrimination does not stop here, of course. Thirty years after Landsteiner’s blood-type discovery, Charles R. Drew, a prominent African American physician credited as the “father of the blood bank,” discovered a methodology for collecting, processing, and storing blood plasma. Drew led the effort to transport desperately needed blood and plasma to Great Britain during WWII. The program became a model for the Red Cross to mass produce dried plasma in 1941, with Drew as assistant director. But just two months after launching the program, the Red Cross decided to segregate blood from Black donors. The official policy was “for reasons which are not biologically convincing but which are commonly recognized as psychologically important in America.” In response, Drew resigned from his post, penning a letter to the director of the federal Labor Standards Association: “I think the Army made a grievous mistake, a stupid error in first issuing an order to the effect that blood for the Army should not be received from Negroes. It was a bad mistake for 3 reasons: (1) No official department of the Federal Government should willfully humiliate its citizens; (2) There is no scientific basis for the order; and (3) They need the blood.”

Unlike the blood segregation that targeted Jewish and Black communities, the MSM blood ban initially came out of a genuine public health crisis. In the early 1980s, the policy was born from a fear of a then-unknown affliction decimating entire communities in a matter of a few years. When the FDA first announced the 1982 blood ban, it included other demographic groups where HIV was prevalent, such as Haitian immigrants. In response, leaders of Haitian American organizations protested the discriminatory policy, saying the move would only stoke stigma and bias. Once the scientific community identified HIV and came to understand the virus, how it was contracted, and how to prevent its transmission, the FDA quickly developed and licensed 10-minute HIV testing kits for blood donations. By December 1990, the FDA lifted the ban on Haitian donors, and added new risk-based screening questions for all prospective donors in its place. By 1999, every blood center in the United States was using nucleic acid testing for all blood donations, regardless of the race, gender, or sexuality of the blood donor. Our science has advanced to the point that the blood ban is no longer about thwarting certain viruses; it’s about thwarting certain people.

As the “gay blood ban” is lifted across the world, U.S. policymakers and practioners should similarly distinguish between science and stigma, weighing not just the social cost, but the medical cost of preserving the MSM ban. We are confronting a pandemic that demands more blood than we have available. Even before COVID-19, fewer than 5% of eligible Americans donated blood products. The Williams Institute found that an additional 360,600 men would likely donate 615,300 additional pints of blood each year if the current MSM ban were lifted. In many ways, this moment harks back to the fear, isolation, and grief that Jews know all too well. And once again, we have to reconsider and scrutinize the policies that led us here and find a course of action that saves the most lives.

Jacob Fertig is a documentary filmmaker and impact producer based in New York City. He is Co-Founder and Managing Director of Denizen Studios.