Books for Kids With Anxiety

A recent spate of titles can help children struggling in our scary world

Between COVID-19 fears, the tangible evidence of America’s racism and anti-Semitism, and the uncertainty around going back to school, kids today are stressed. They see and hear (often more than parents realize) that the world is in a distressing state. Even very little ones pick up on the emotions of the adults around them.

Kids are intuitive and empathetic. And their world is in disarray. Remember, most of them were picked up from school one day in March and haven’t seen their friends since. It’s a detonation of everything they knew. I’m hearing lots of stories from fellow parents about their spawn regressing, acting out, sleeping way more, desperately missing their friends, asking repeatedly about the precise mechanics of virus transmission, exclaiming over phrases they’ve heard the president or his minions yelling on TV, worrying about images of police violence they see all around.

Some kids may wonder aloud over and over about the health of the class pet. Or fret about mold or bugs or rodents in the school building resulting from leftovers being abandoned in still-locked lockers for five months. (Ask me how I know.)

Fortunately, there are a lot of diverse children’s books (many published within the last couple of years, many with Jewish characters) that can help. Even if your kid is reading independently, you and they can still enjoy picture books together. Sit close together to read (snuggle op!), talk about the art as if you’re in a museum, point out the use of color or framing, and discuss the efficiency and tightness of picture-book text. Picture books are for everyone.

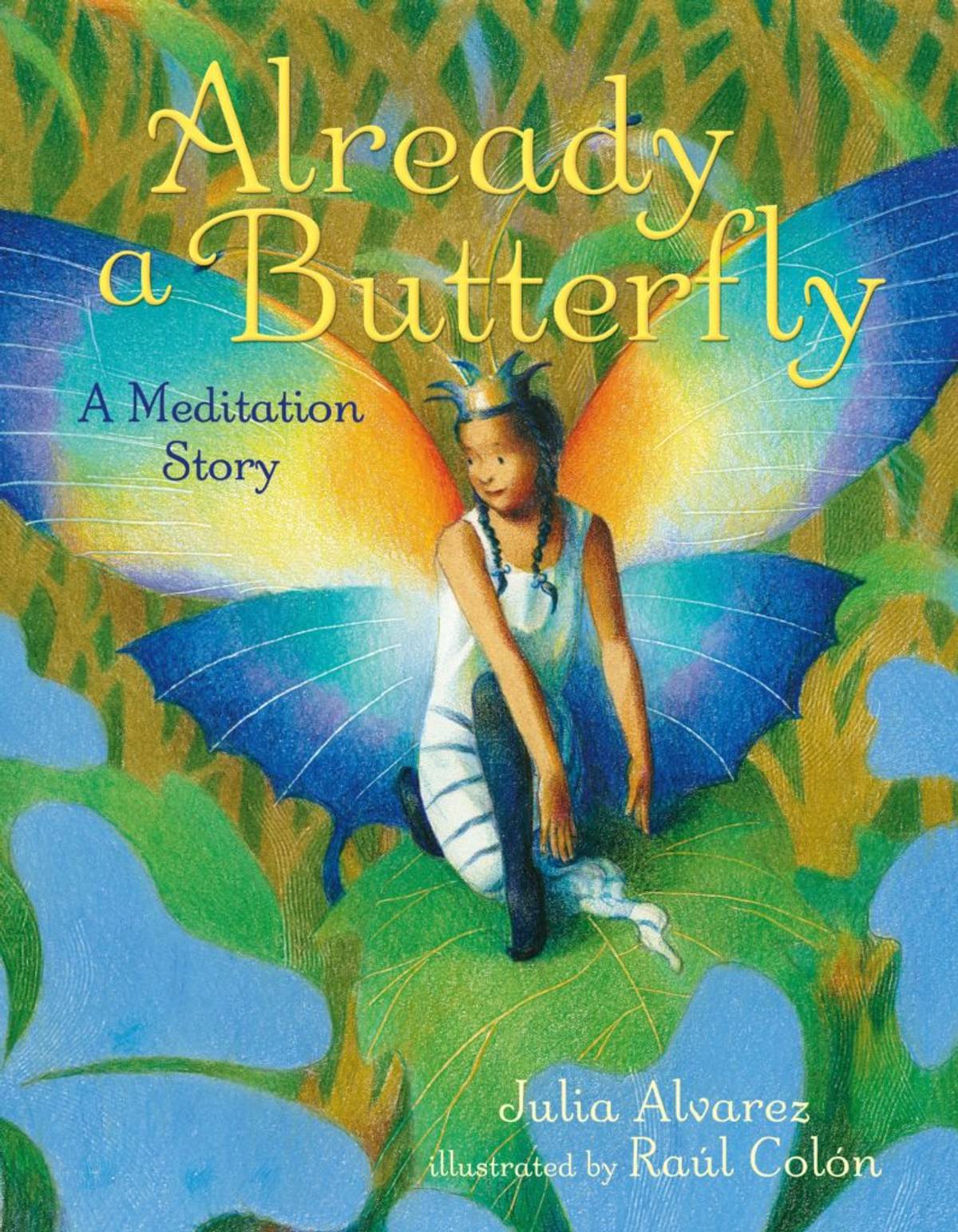

Helpful options include 2020’s Already a Butterfly, with poetic text by Julia Alvarez and luminous art by the brilliant Raúl Colón. Colón works in nearly incandescent watercolors, lithograph crayons, and colored pencils, then uses scratch tools to create grooves and textures and an inviting sense of tactility. Already a Butterfly is about a stressed-out new lepidopteran named Mari who fears she’s already lousy at being a butterfly. (“Instead of falling asleep, Mari counted the flowers left to pollinate; the days, hours, and minutes before she had to migrate; the mate she had to find; the eggs she had to lay.”) Then a bud named Bud teaches her how to breathe slow and deep and how to appreciate all she’s accomplished in her chrysalis (“eating, eating, eating all those leaves, shedding your skin every time you got too big”). She can just breathe and be and appreciate the beauty of the world. She’s already a butterfly; she doesn’t have to worry about being a butterfly. “Bud’s words were soothing like a lullaby,” Alvarez writes. “But instead of putting Mari to sleep, they were waking her up to the sounds, sights, and smells around her. Flowers were blooming everywhere: bluebells and purple asters and buttery yellow dahlias and dramatic black-eyed Susans. Had there always been so many kinds? Were their scents always so delicate and enchanting? How long had the crickets been serenading the field with their one-string fiddles?” Mari learns to be in the moment (though Alvarez never uses that cliche) and when Bud disappears and becomes a flower, she takes some of his pollen to carry with her everywhere.

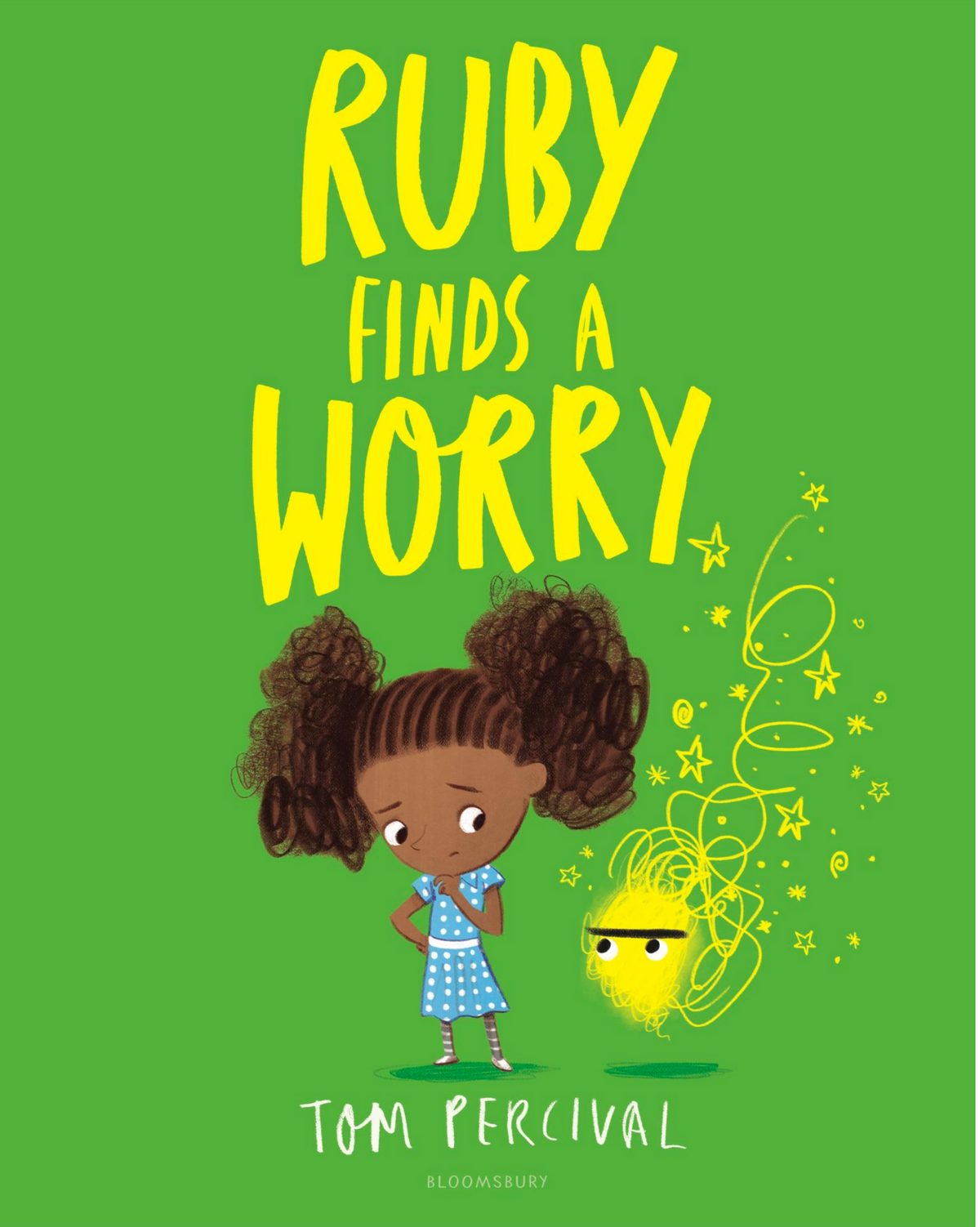

Ruby Finds a Worry by Tom Percival has simpler text and a cuter, more kinetic flair. Ruby is a happy kid in a blue polka-dot dress and contrasting stripy leggings. But a worry—a big beetle-browed yellow scribble that just keeps getting bigger—starts following her around. She can’t shake it until she meets a sad-looking, spiky-haired little boy who has his own worry, a light blue splotch with the same heavy unibrow as Ruby’s worry. By asking him about his worry, then talking about her own, Ruby helps both of them cope.

Me and My Fear by Francesca Sanna is another visually sumptuous option by the author of The Journey, a profound picture book about the refugee crisis. An unnamed little girl has been accompanied by a secret, tiny friend called Fear for as long as she can remember. “Fear has always looked after me and kept me safe,” she says. But as the girl gets settled in her new country, Fear grows bigger and bigger. It won’t let the girl go outside to explore her neighborhood; it makes her feel angry and isolated at her new school. But then she sees a boy drawing, and the two begin to make art side-by-side. They don’t need shared spoken language for that. When they go outside at recess together and a dog barks behind a fence, the little boy freaks out. “He has a secret Fear like me!” the little girl exclaims. She starts to learn the language of her new country and discovers that lots of kids have a Fear of their own.

Here and Now by Julia Denos, illustrated by E.B. Goodale, (the duo behind the equally lovely and reassuring Windows) is another recent entry in the genre. It’s instructional but not didactic, teaching kids how to ground themselves when they feel anxious by noticing exactly where they are in space. Denos’ text is spare and sparse, soothing. “Right here/right now/you are reading this book./The book is in your lap/or in your hands/or in someone else’s.” Goodale’s art, painted and drawn by hand and then collaged in Photoshop, is richly saturated and colorful, with a bit of an Ezra Jack Keats vibe. It feels kind. (I don’t know how art feels kind. It just does.)

Finally, we have two classics of the anxious kid genre: Wemberly Worried, by kidlit all-star Kevin Henkes, featuring a big-eyed white mouse with scared/sad eyebrows, perpetually clutching a bright yellow stuffed bunny. Her parents keep telling her, “You worry too much” and “Don’t worry,” phrases that don’t help at all. She’s terrified about the first day of school, but Mrs. Peachum introduces her to Jewel, a big-eyed brown mouse with scared/sad eyebrows, clutching a stuffed blue toy kitty. “This is Petal,” Wemberly says, showing her lovey to Jewel. “This is Nibblet,” says Jewel. A friendship is born, and school no longer feels so worrisome.

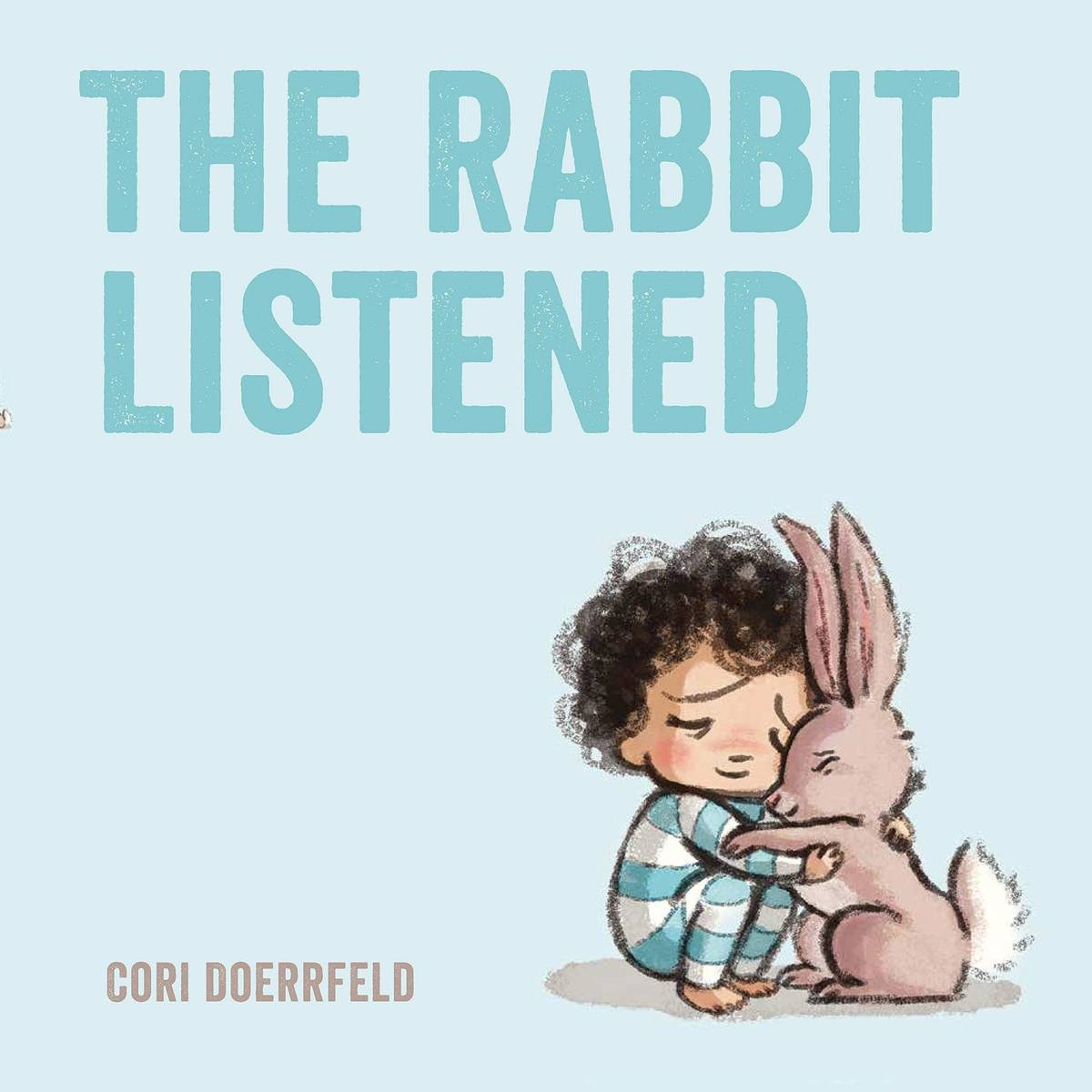

The Rabbit Listened by Cori Doerrfeld is only 2 years old but already on every librarian’s emotion-regulation-for-preschoolers list. Kids as young as 2 can understand the inchoate rage and sorrow that Taylor (a curly haired, PJ-clad toddler of indeterminate gender) feels when an elaborate block construction is knocked over. Taylor is a little island in a sea of purple space that gives a feeling of isolation. Various funny and expressive animals show up, all certain they know how to make Taylor feel better. None of their suggestions are right. But then Rabbit shows up; all Rabbit does is listen. By listening, Rabbit helps Taylor sort through their feelings and provides the space for Taylor to consider building something new and amazing.

There are some great new and not-so-new choices for middle-grade readers, too. A big name for this age group is Raina Telgemeier, whose hugely popular, autobiographical graphic novels are in perpetual demand in elementary school libraries. Guts is about young Raina’s experiences with anxiety and therapy. Her emotions manifest themselves in puking and farting and fear of puking or farting (#relatable). Her anxiety begins to isolate her, and her parents finally take her to a therapist in layered clothing and chunky earrings and ballet flats in the eternal Eileen Fisher hippie style of every therapist I have ever had. Raina’s fears are depicted as pea-soupy waves circling her; she learns when they start to spiral to focus on the anchoring feeling of her feet touching the floor, on breathing, and on the word “try.” In a slightly too tidy ending, Raina learns that a lot of kids see therapists and have challenges of their own. Middle-grade readers can be hard to please, but Guts seems to please all of them.

Maybe because we Jews are so good at acknowledging our anxiety, and maybe because the diverse books movement is finally acknowledging Jews, there are a lot of fab new books with anxious Jewish protagonists. Fish Out of Water by author/crafter Joanne Levy comes out later this month. It’s an easy-to-read tale (lots of white space! reluctant-reader friendly!) about a boy named Fishel who’s worried about his bar mitzvah project and about his place in the world. He wants to learn to knit and take the JCC’s seniors Zumba class, but his bubbe and stepfather and friends make him feel like his interests are unmanly. Sadly, his mom initially fails to stick up for him. Happily, everything gets knitted up neatly at the end and Fish’s bar mitzvah is a triumph of shared community and acceptance.

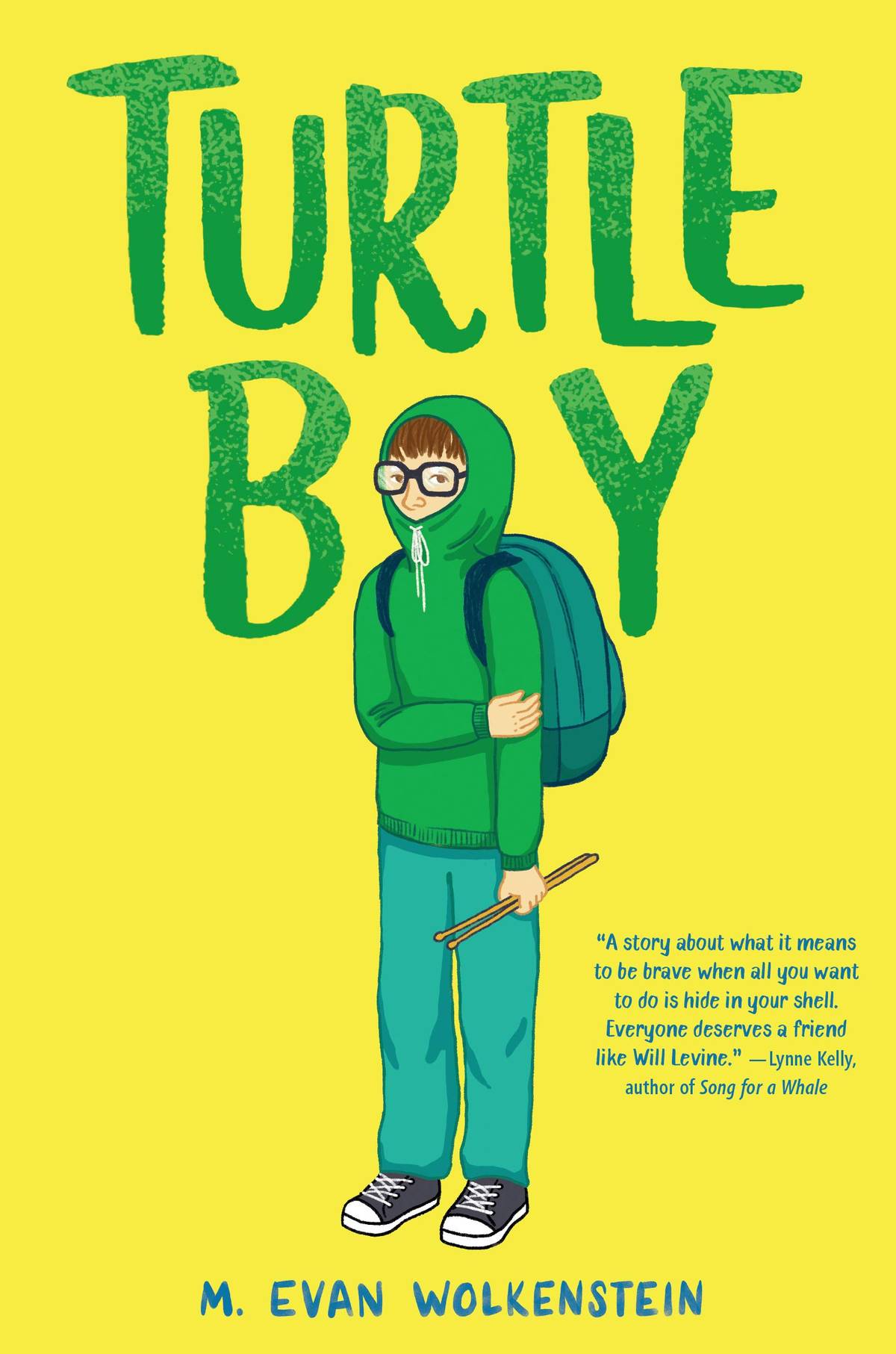

Turtle Boy by M. Evan Wolkenstein is also brand new, extremely Jewish, and focused on bar mitzvah prep. But it’s longer and more complex, a good choice for accomplished readers. Will Levine is having a crappy seventh-grade year. The popular guys bully him for his weird-looking, barely there chin; he’s facing a terrifying-sounding surgery to make it easier for him to chew; his illicit turtle collection is at risk, as is the marsh the turtles come from; and his congregation’s “Yo Semite” T-shirt-wearing, junk-food-obsessed, Grateful Dead-listening rabbi forces him to visit a terminally ill kid, RJ, in the hospital for his mitzvah project. After a rocky start, Will and RJ hit it off, and RJ tough-loves/guilts Will into facing some of his fears. Sure, there’s a little bit of the “dying person as device to help surviving person learn to LIVE LIVE LIVE” dynamic at play, but the writing is so specific and so quirky, and Will is such a great character, I forgive. The depiction of the soothing power of really loud music (“everything is pulsing like a single slamming heart”) and the feeling of release and accomplishment after riding a roller coaster (“We’re falling, we’re flying, we’re tumbling—all my organs plunge into my feet, and my lungs are being crushed, and the world is rocking and shaking ... Max and I squish against each other like wet clothes spinning in a drier ... I think maybe I’m getting the hang of this, maybe I’m not going to die, but then we rocket up, float, and plunge down a spiral as if we’re going down a drain and falling through the center of the earth”) are delicious. You know where it’s going, but the journey is very satisfying, a witty and cathartic weep-inducer.

A slightly older title, 2016’s Finding Perfect by Elly Swartz, is about a year in the life of a 12-year-old girl with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Molly Nathans’ mom has left the family for a huge management job at a Jamba-juice-like concern; it’s unclear whether she’s coming back. Her dad is overworked. Her little brother keeps messing with her stuff. She’s determined to win a poetry slam so her mom will have to come home to attend the fancy dinner for the victors. She’s convinced she has to seem “perfect.” And her repetitive behaviors start to spiral. Her glass animal collection has to be in a certain order, with a certain number of inches between each animal. She can’t leave a single eraser mark on her schoolwork. She needs to count to herself in multiples of four. Can she get a handle on her compulsions before they destroy her life? (Spoiler alert: Yes.) The book is informed by mental health research and expertise, and it makes something terrifying seem ... if not conquerable, then manageable.

And Newbery Medal-winner Rebecca Stead has a new novel out, always a reason to celebrate. The List of Things That Will Not Change has garnered eight (8!) starred reviews. Bea is a girl of big feelings and impulsive gestures whose life is undergoing a lot of change. Her dad, who’d gotten amicably divorced from Bea’s mom after coming out as gay, is now getting married to his longtime boyfriend, Jesse. Not everyone in their community—or in Jesse’s own family—is supportive. Bea also worries about her mom’s feelings, about her cousin Angelica’s Bell’s palsy, and about Jesse’s daughter’s apparent lack of eagerness to have a sister. Stead’s writing is exquisite; she describes emotions like no one else. Bea tells us, “When I get mad, I feel cold. I don’t feel huge, like when I’m happy. It’s more like I’m filling up with something that runs over my edges and rises up behind me like a gigantic pair of bat wings.” Stead also offers insight from Bea’s therapist, Miriam, in a way that doesn’t derail the story. “Miriam says that a lot of the time, behind the feeling ‘I hate this’ are other feelings,” Bea says. “Like maybe ‘I’m afraid of this’ is hiding behind ‘I hate this.’ And maybe hiding behind ‘I’m afraid of this’ is ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen next’ or ‘I don’t know if I can do this.’ There are a lot of feelings behind feelings.” The book is compulsively readable and not at all reductive. So satisfying.

Literature isn’t a substitute for mental health care, of course. But books are a terrific way for kids to see they’re not alone in their worries, that fear is part of life, and that stuffing anxiety into one’s closet and not talking about it isn’t a long-term solution. Feelings journals, self-help books, and anxiety worksheets can be helpful in a therapeutic context, but powerful storytelling is good healing for everyone.

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.