Both Sides Now

A recent visit from an old friend left us both wondering about the choices we made about family and career

After months of excited emails and Facebook messages, I was finally going to see Joanie—my favorite friend from high school—in Manhattan last November. Visiting from Israel with her family, she planned to sneak away late Thursday night to meet me downtown. I made it clear that nobody else was allowed to come. This was the first time I’d be seeing her in five years.

Worried that I’d gained weight and wrinkles, I tried to look good for her—dressing in chic black, with silver jewelry and makeup, my hair dyed back to its original chestnut color. When we hugged at my door, I took in her loose top, long skirt, and hiking boots, a headband holding her gray hair. She’d aged, too. Recognizing her luminous smile, I relaxed.

Although we were still Michigan girls at heart, our worlds had long ago diverged. After a 30-year struggle, I was a published author finally able to afford the literary scene in Greenwich Village I’d coveted for so long. I exalted Oprah and Gloria Steinem, celebrating women’s rights to have an important life, child-free. Joanie also had a book out—teaching mothers to breastfeed—and went back to school to become a nurse/midwife. But most of her time was dedicated to mothering her own six kids. Now, at 55, she was a grandmother of five.

In my New York apartment, as my old comrade showed me photos of her grown children, I was shocked by how jealous I felt. Suddenly, I was afraid I’d wasted decades.

***

I met Joanie when I was 15 and we were fellow left-wing classmates in the Midwest. She was a year older, a gorgeous light-haired, green-eyed hippie I looked up to. (Think: Jennifer Lawrence in bell bottoms and love beads.) My dad was a doctor, hers a dentist. We both skipped two grades and shared a passion for literature, Bob Dylan, cigarettes, joints, and a cute mustachioed senior named Mark whom we both dated (luckily, during different terms). After I visited her college dorm during my senior year of high school, pleasantly struck by its co-ed bathrooms, I enrolled at the University of Michigan. We took separate college trips to the Holy Land, where Joanie fell for an Israeli. While I returned home, she made aliyah. By the time I’d finished grad school at 22, she had a husband, a house, and—as she joked—a bunny in the oven.

I viewed being barefoot and pregnant as prehistoric. I wanted to be a serious career woman in the urban jungle, playing solo.

I visited her a few years later, as a 27-year-old journalist on foreign assignment. A lipstick feminist, I was dismayed to see her Jerusalem home disheveled, with three toddlers she was chasing and diapering. She seemed warm and naturally maternal. Yet I was disappointed when she became Orthodox, dressing dowdier, forgoing her physical beauty for a higher calling, exchanging Baudelaire for breastfeeding. She took her husband’s name and had more offspring. My mother’s generation had large broods to compensate for Holocaust losses; Joanie was my only contemporary doing so.

I was proudly anti-traditional; procreating for religious reasons seemed laughable to me. I followed the rules of confessional poetry and psychotherapy, which eased my relationship and addiction problems. I became more liberal, skipping Passover Seders and family rituals, quitting my secure job, and dating Catholic, WASP, Baptist, and Muslim men of all flavors. “You’re freelance everything,” my mother lamented.

I was surprised that, in the end, I fell for a Jewish scriptwriter. After we married, when I was 35, I first started to fantasize about having a child. Alas, my husband and I were both Tay-Sachs carriers, with a 50 percent chance of passing on the fatal disease; ironically, picking a mate from my own tribe made the Hebrew mandate to “go forth to multiply” virtually impossible. A fertility specialist recommended IVF with genetic engineering but ominously warned they couldn’t be certain if the fetus would be Tay-Sachs-free until an amniocentesis, 14 weeks after conception. It cost $20,000 for one round that our insurance wouldn’t cover. Infertility treatments were much cheaper in Israel, and I considered immigrating—like Joanie, and my cool cousin Shelley from New Jersey, who had four kids there. But my husband and my work were stateside.

So we stayed. Just the two of us. Instead of babies, I had books.

***

“I witnessed a stabbing outside my office last week,” Joanie told me on our recent rendezvous, as we took a stroll around my neighborhood. She was shaken by the rising terrorism against civilians erupting around her. “We bring mace and hammers with us on buses. My two middle boys are soldiers. We’re terrified every day.”

“My 20-year-old sabra niece guarded a murderer at the courthouse,” I said, showing her pictures. I’d recently read a distressing article on how Israel might not survive, feeling intense solidarity and fear.

My old rabbi once told me Judaism was a religion, a nationality, and a culture, insisting you could embrace any branch and be a good Jew. I was culturally inclined. I’d exalted books by Philip Roth, Yehuda Amichai, Grace Paley, Cynthia Ozick. I wrote for Jewish publications and spoke up for our tribe in secular papers. I donated to Friends of Magen-David and Hadassah Medical Center. I considered myself a good person. But now, imagining Joanie’s kids in the army with my cherished cousins, praying they’d stay safe, hidden emotions ambushed me.

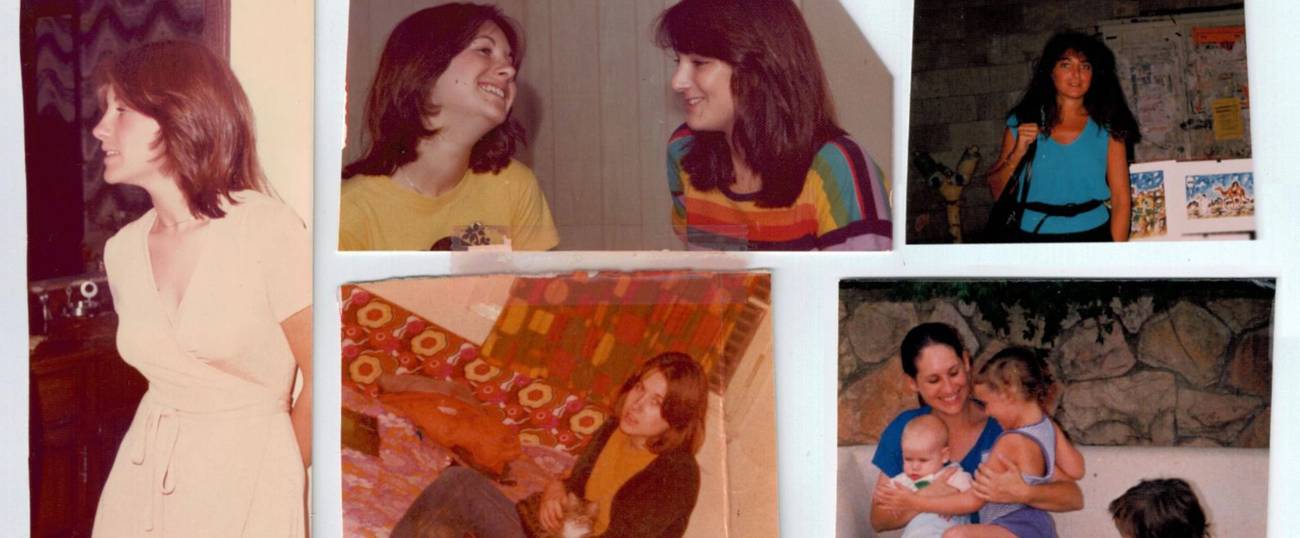

I didn’t know whether it was reports of Palestinians stabbing innocent citizens that stirred me, a menopausal haze, or my intense late-night reunion with Joanie after so long. But the photograph of her four burly sons and two lanky daughters surrounding her seemed surreal, as if her body was a portal a whole new generation had stepped out of. I felt inadequate, an empty womb standing by the sidelines of her glory. Since my brothers had intermarried, I was the only sibling of my clan who’d wed under a chuppah. Yet I was just an American Democrat feeling bizarrely nationalistic toward a place I’d only been a tourist, like “an aging Diaspora Jew on a junket with cheap feelings,” as David Mamet called himself on a tour of Israeli bombing sites. I wasn’t even making plans for a return trip to show support.

Although Rosh Hashanah had passed, I pictured reading over the book of my life—and I was coming up short. If I wasn’t a mother, with my big brains and bigger mouth, I should have led more than a minion of feature journalists. But the myopic goals through graduate school and beyond diplomas that I’d longed for—and achieved—only included publishing and landing a decent Manhattan apartment.

Suddenly I felt haunted by a birth control mishap at 20 with my first love, a smart, curly-haired Jewish pre-med I’d dated for six years. When I was two weeks late, he’d offered his hand. Unlike Joanie, I didn’t drop out of school to marry and bear a child. Deciding I was too young, I terminated the pregnancy. I wanted to learn more, take care of myself, be financially stable. Fifteen years later, in a childless union with my bashert, it felt like God was saying: I gave you the power to give birth but you don’t get to decide when. You waited too long. Looking back, for the first time, I felt regretful: We should have fought harder to conceive. I could have used donor eggs or adopted.

Reading studies that showed the more educated a woman is, the fewer children she has, I saw Joanie as a feminist superhero: a strong mother and grandmother, repopulating her country while nursing others. She was holier than I was, sacrificing everything material. I’d struggled decades to afford my city, love, and time alone. She’d nurtured 11 babies; I worried I’d wasted my hours on 11 books, inanimate objects, midwifing only my own career. From this older perch, I was awed by the legacy she’d made to carry on her bloodline and ideals.

Then she started complaining of the tiny Brooklyn Airbnb where she was staying with her husband and kids, all they had means for this trip. “I argued with my sons today,” she said, “it’s too hard for all of us sharing one bathroom.” Even with two jobs, she and her husband were drained. They’d downsized as I’d expanded to a three-bedroom, three-bath home/office in New York. I guessed our monthly costs equaled her annual rent. Coming back to my apartment, I worried she saw me as a frivolous urbanite, using up so much space for just two people and our work.

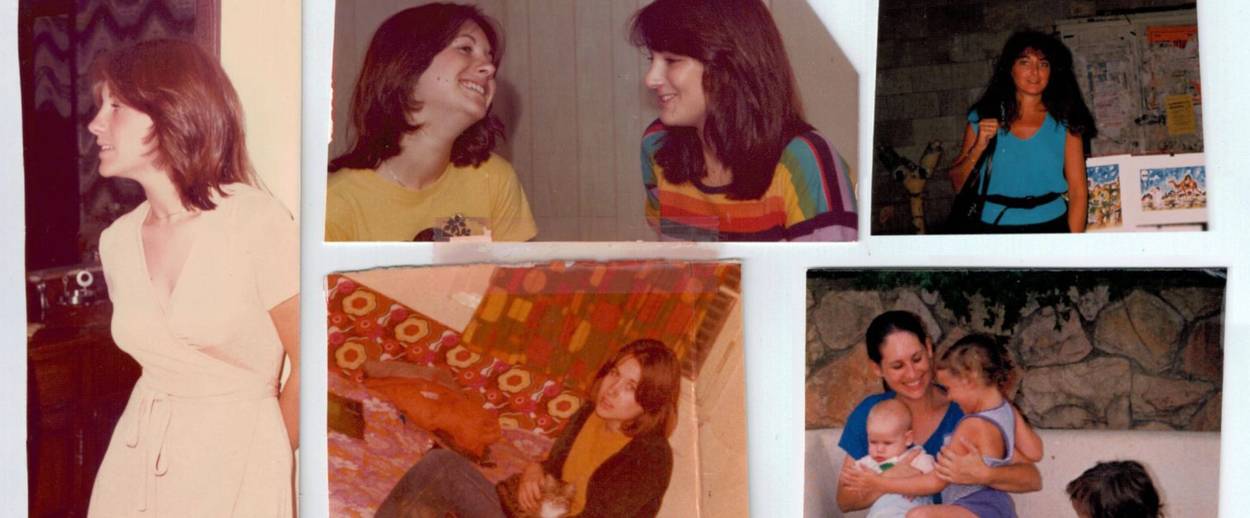

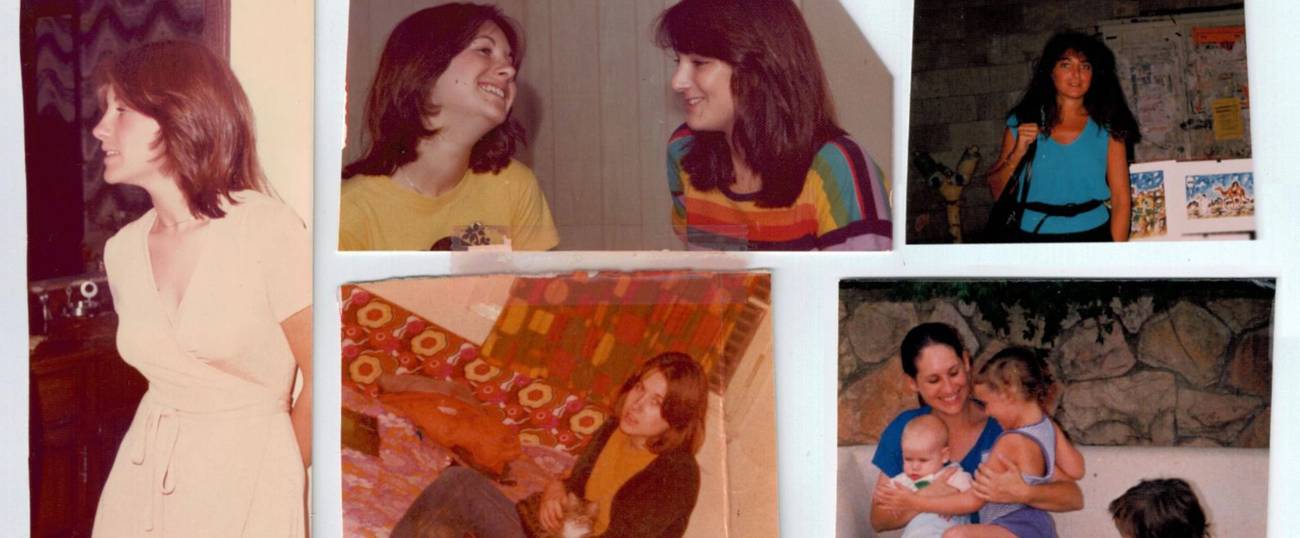

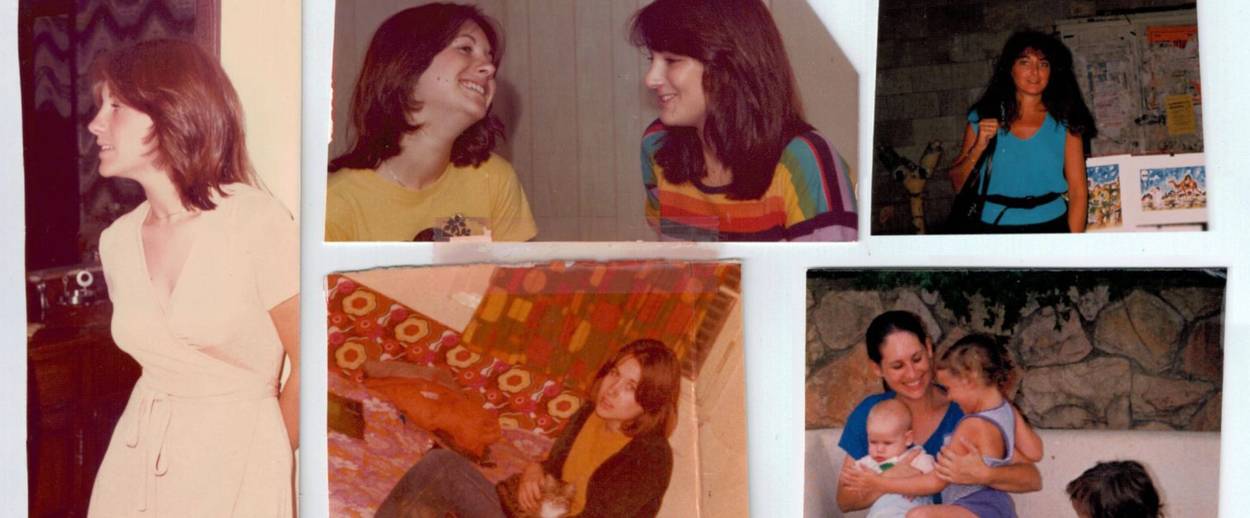

“Can I see your old photographs?” she asked quietly.

“Sure.” I pulled out my worn album. She took pictures of a page of herself decades ago, in a sexy, tight, pink low-cut dress at my Sweet 16. I analyzed why our paths had diverged: Because I was an Aquarian to her Capricorn? Her only sister was five years younger while I had three science-brain kid brothers close in age whom my doctor-father preferred. My siblings had given my parents five grandchildren. Resenting being “Mommy’s Little Helper,” I’d completely rejected the caretaker role. I’d read that writing was a way “to talk without being interrupted.” In Mrs. Lerhman’s first-grade class, I’d won an award for filling out the most notebooks in the history of Shaarey Zedek Hebrew School, 1,200 blue notebooks crammed with Hebrew letters I couldn’t read. Maybe I was still trying to please my difficult dad, who believed “achievement was redemption,” while Joanie had been closer to her father.

Yet most astounding was how alike Joanie and I still were: overly sensitive, analytic, happily married to warm men. We’d each coincidentally quit smoking, toking, and drinking at the same time a decade ago and battled overeating. After The Jerusalem Post excerpted my last book, she rushed to mail me copies. When her lookalike daughter moved here, I gleefully showed Hila my haunts, time warped, as if I was 20 and hanging out with my college-age Joanie again. Despite only catching up in person twice in a decade, we remained indelibly close.

At midnight, I treated Joanie to a cab back to Brooklyn, feeling a bit forlorn. The next day my ravishing 10th-grade pal popped up on my Facebook newsfeed in the pink dress from my Sweet 16. Afterward she stunned me with a long heartfelt email, admitting, “I felt intimidated around you, an accomplished professor at a prestigious university, publishing so many books, looking gorgeous with your long dark hair and shoes to die for while I’m just a fat, frumpy bubbe.” I laughed out loud at our mutual envy.

“Are you crazy?” I responded. “The whole time you were here, I was so jealous of your beautiful kids and grandkids and patriotism and all you’ve done for our people. It made me feel completely inadequate.”

She answered with a string of yellow laughing emoticons. Maybe nobody wins everything they want in life. Our get-together had made us each feel rueful. But it also made us both feel blessed.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Susan Shapiro, a Manhattan writing professor, is author of several books her family hates like Barbie: Sixty Years of Inspiration, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, The Forgiveness Tour, and her writing guide, The Book Bible. Follow her on Twitter at @Susanshapironet and Instagram at @profsue123.