The Boys in the Band

The young musicians who became the pride of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum

There once was a time when no public Jewish event in New York City—from the 1899 dedication of a new wing of the Home for Aged and Indigent Hebrews on West 105th Street in Manhattan to the 1907 cornerstone-laying of Temple Emanu-El’s sanctuary in Borough Park, Brooklyn—was complete without the Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band. Given all the speechifying that typically characterized these formal occasions, the band’s presence on the bunting-laden dais added just the right amount of oom-pa-pa, transforming a dutiful, if dull, ceremony into a spectacle.

The band’s impact was both sonic and visual. Wielding brass instruments, this cadre of anywhere from 60 to 80 musicians between the ages of 10 and 16 was given to performing rousing, up-tempo, catchy tunes—the kind that prompted audiences to clap their hands and move their feet in time to the beat. The band was all dressed up, too: in eye-catching military uniforms of indigo blue that bore the letters “HOA” around the collar and on the brim of their smart little caps.

Sight and sound colluded to make the Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band at once endearing and vaguely comic. Eyewitnesses frequently commented on the youthfulness and earnestness of the musicians, of how their faces shone as brightly as their highly polished brass trumpets and cornets, and, most especially, of their resemblance to “Lilliputian soldiers.” The Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band, declared the Jewish Messenger in 1902, “is the biggest little band in the United States and it is a happy band, if smiling faces are criterions [sic] to go by.”

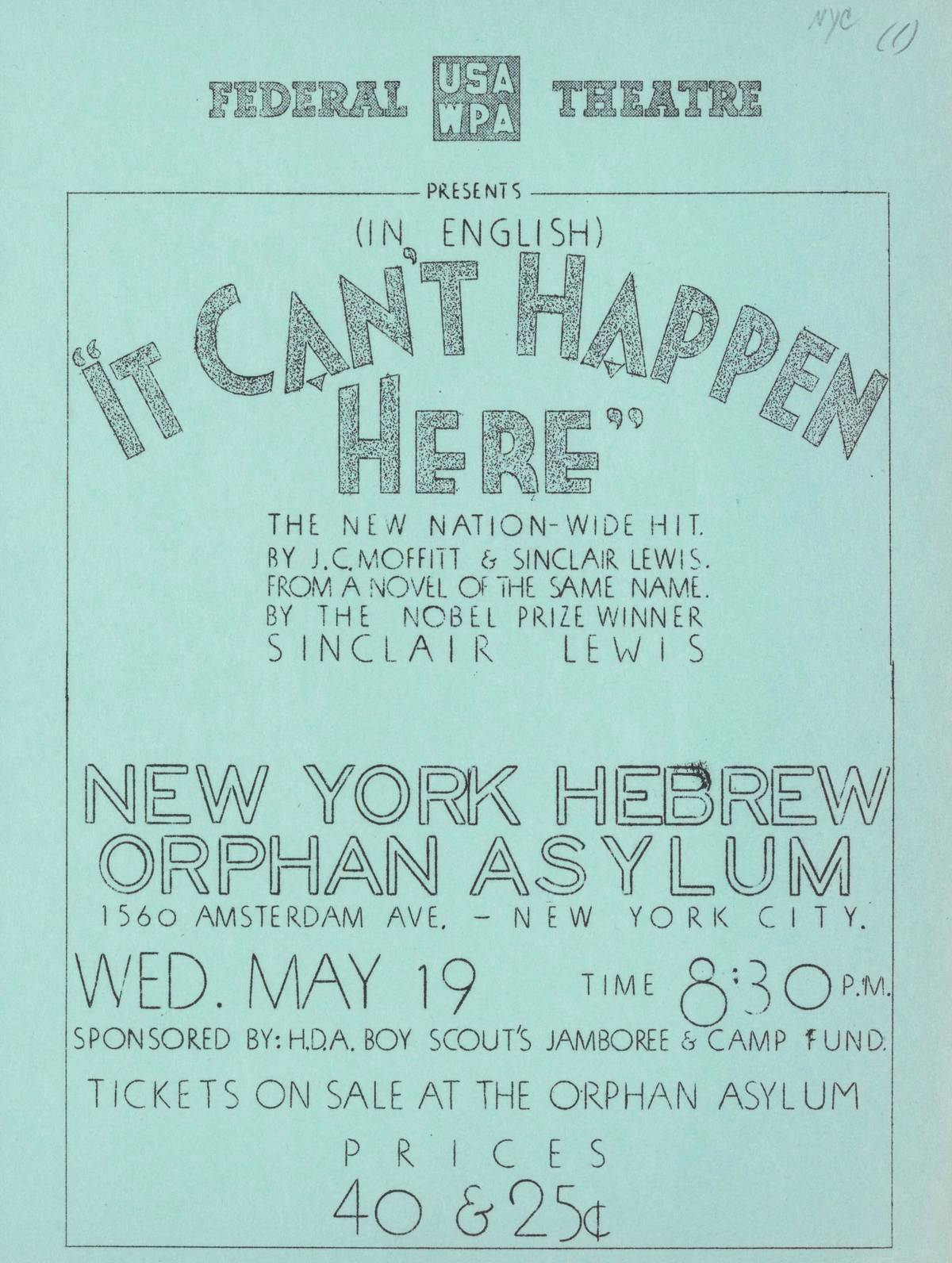

The public face of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, the band was central to its educational philosophy, which was designed to transform its motherless and fatherless charges—or “inmates,” as they were then called—into well-rounded, well-fed, and well-adjusted citizens. “There are no Oliver Twists in this institution,” insisted one of its officials in connection with the several hundred orphans who lived in the imposing facility at 136th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, in upper Manhattan.

When the musical ensemble was first established in the 1870s, its future was anything but assured. Shaky finances, along with a revolving door of both potential recruits and band leaders, militated against its stability. By the turn of the 20th century, it had found its footing as well as its funding. Together with the ice cream treats, summertime excursions, and turkey dinners provided by the home’s donors, a sufficient amount of wherewithal was generated annually with which to clad the “lads” in handsome uniforms, equip them with well-tuned instruments, and offer twice-weekly lessons in sight reading, theory, and harmony.

While it was a source of great pride, a feather in the institution’s cap, when some members of the band continued to pick up an instrument and perhaps even play professionally after they had left the facility, the orphan asylum’s commitment to musical education wasn’t so much a matter of vocational training as of social engineering: keeping boys off the streets by instilling in them the traits of punctuality, obedience, and discipline, as well as “manliness and a fine carriage,” or so reported the institution’s superintendent in 1893.

The Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band was a boy band, through and through. Not until rather late in the day were female inmates given the opportunity to make their voices heard, but even then, only within the very limited compass of the institution’s synagogue choir or a class in choral singing. For much of its history, the asylum’s curriculum followed strict gender norms: The girls burnished their skills as homemakers, learning how to sew, embroider, and keep house, while their male counterparts got to toot their own horns.

At the time, this imbalance didn’t seem to ruffle too many feathers, though I suspect that at least some of the female inmates might have chafed under the institution’s prescriptions. What did occasion a mild slap on the wrist was what some of the neighbors took to be the making of excessive noise, especially when the band rehearsed its music and its moves outside. The Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band is a “nuisance,” publicly complained one local resident in 1909, claiming that it was bad enough that the band’s bugle calls woke him up in the morning without his having to listen to its repeated playing of “The Star Spangled Banner,” an experience he found “excruciating and painful.”

More serious by far was the claim that the Hebrew Orphan Asylum paid scant attention to Jewish music. Writing in 1918 in the Musical Age, a weekly magazine dedicated to classical musical expression, reporter Morris Clark suggested that the limited presence of “Jewish numbers” in the band’s wide-ranging repertoire ought to be rectified forthwith. Perhaps band members might be inspired to “take up more Jewish music” by following the example of the Jewish Legion, he advised, extolling the ways in which its “young warriors” were both animated and inspired by playing and marching to the tune of “Hatikvah.”

Clark’s advice appears to have been heeded: According to a detailed list of the Hebrew Orphan Asylum’s repertoire carefully assembled by music historian Carol Shansky, the author of a detailed study of the band, the Jewish national anthem eventually took its place alongside “Swanee,” “Embraceable You,” the “Triumphal March” from Verdi’s Aida, and pop tunes of the day.

Whether making music or noise, the Hebrew Orphan Asylum Band gradually expanded the venues at which it performed, marching more and more frequently in urban parades like those associated with Columbus Day and appearing regularly on radio broadcasts throughout the interwar wars. It may never have become a general household name but it certainly wasn’t for want of trying. “The Hebrew orphans know how to play,” observed the Evening World in 1917, in the wake of one of its performances. “They played as if they wanted everybody present to get it into their heads that they were no strangers in this land, that they were all Uncle Sam’s lads.”

When, decades later, at the height of another world war, the Hebrew Orphan Asylum closed its doors, a consequence of both dwindling finances and a sea change in social welfare policy that substituted foster care for institutional care, the band’s long and lively run came to an end. It didn’t take long before its history vanished into thin air, much like the dying notes of “The Gang’s All Here,” one of its frequently performed, signature songs.

Jenna Weissman Joselit, the Charles E. Smith Professor of Judaic Studies & Professor of History at the George Washington University, is currently at work on a biography of Mordecai M. Kaplan.