Bright Lights, No City

After months of hiding in our Manhattan apartment during the pandemic, we finally got a week away—and almost immediately began missing the noise and craziness of New York

Like many urban dwellers, my husband, Charlie, and I hid in our Manhattan apartment for four months during the pandemic. We were glad to be employed, teaching online, but because of Charlie’s age and medical issues, I felt protective, gathering groceries outside, keeping him in. COVID-19 lockdowns made us claustrophobic. Unlike some friends, we had no summer home to flee to.

We were proud of our New York blood. All four of our parents were from poor Jewish families who’d crammed into small Brooklyn or Lower East Side tenements. They’d toiled to escape the city and its density, crime, and rats, fleeing to the bucolic burbs—their American dream. But Charlie and I were city mice. After college, we both rushed (separately) back to Manhattan. Creative misfits and night owls, better walkers than drivers, we were instant urbanites, willing to brave tiny walkups before we could swing buildings with elevators. When I moved to the East Village—a mile from where my doctor dad hailed—he’d yelled, “You’re doing this to spite me. It’s still the Lower East Side. The Realtors are lying!”

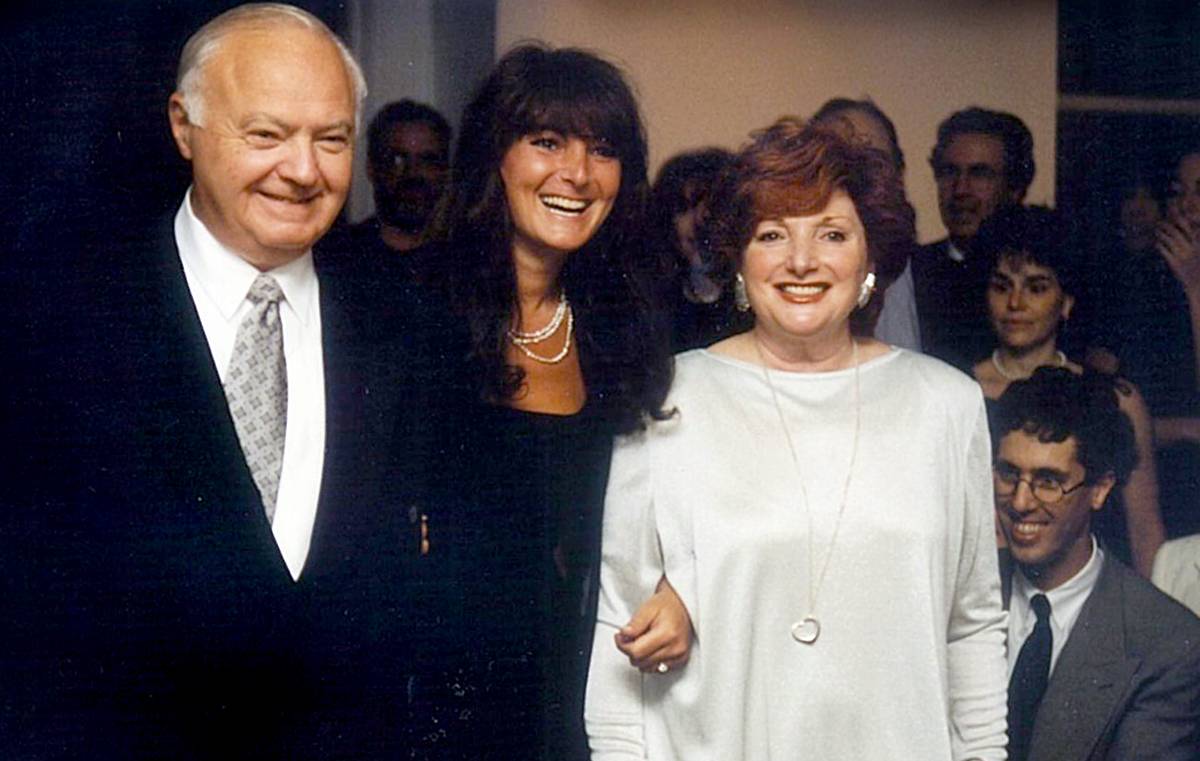

He was only pleased to return once, when I wore black to marry my groom at a late-night SoHo dance-fest that Charlie’s father, a judge, officiated. A reporter covering our wedding deduced the criterion I’d used to choose my groom: He was the least likely person to ever make me sleep in a tent. (Then we were married again the next week by my parent’s rabbi, under a chuppah—the closest I’d ever get to tenting.) Charlie landed a TV job and I taught and freelanced, but we had to borrow money from both sides to buy our dream two-bedroom downtown. My folks flew in again for my first book party. But since it was a risqué memoir, our relatives kept asking them, “How are you holding up?” as if they were making a shiva call.After decades of struggle, we paid off all our loans, feeling like we made it, never envisioning a virus reducing our vibrant oasis to Zombietown.

As the pandemic restrictions eased in May, nightly protests marched outside our window. We applauded our students’ fight for racial equality, but my doctor said joining closely comingled crowds wasn’t smart at our age. Instead I donated to the cause and let low-income kids audit my classes, helping them publish powerful op-eds and essays on injustice. Looting, boarded-up stores, the curfew, and hovering helicopters added anxiety, especially when we knew young people who’d been injured, arrested, and jailed for peaceful protesting. It was hard to work or sleep in the epicenter. Animosity between demonstrators, increased homeless population, and aggressive NYPD presence made our Greenwich Village haven feel like a battleground. For the first time, I wanted out.

Memorial Day, I asked my mom if we could visit the Michigan home where I grew up, on a lake with a pool my father installed. When I’d left for grad school, I never thought I’d beg to return. Nor did I imagine my warm Jewish mother would ever say no, citing health concerns. She felt it was too soon to fly. Since we’d lost Dad two years before, the pool wasn’t even working, she said.

I told my friend Alice—a wine critic weaned on Manischewitz—that I missed home and Charlie missed his kid sister Carol in Connecticut, and his 98-year-old mom, Lucille, who was sick in a nursing home. We hadn’t seen her since the winter, fearing the worst. Stuck alone in a 600-square-foot prewar SoHo walkup, Alice was stressed, too. The sole caregiver for her 95-year-old mother, whom she drove to Long Island to visit, she’d return depressed. I worried about her. We all needed a break.

Alice offered to help us rent a house for a week in Connecticut. It sounded like a perfect plan; we’d be able to see Charlie’s family, and get him some sunlight. Plus we could celebrate a big birthday and anniversary. We couldn’t fly, eat at our favorite café, or have a proper party. Yet we could have a seven-day getaway.

That is, if we could get there somehow. We were weary of public transportation. And like a good New Yorker, I’d let my driver’s license lapse. Alice offered to drive us, and we took her up on her offer—and asked her to stay.

Now I just had to figure out how to book a place online, which I’d never done before.

“Why does Vrbo insist on my credit card before they say if the house is available?” I asked Alice. “Is that kosher or are they ripping me off?”

After being rejected for my first 20 requests, we found a stately, too expensive place an hour away for one week. It even had a pool—Alice loved to swim like I did—and great water views. I packed three black bathing suits and 100 SPF sunscreen. Then I got nervous and needed an emergency phone session with my shrink to analyze my Jewish guilt over the high cost and decided to teach an extra online summer course to cover it. I phoned my brother Eric, a brilliant IT guy, to learn what equipment I’d need and make sure they had high enough Wi-Fi for my Zoom classes. I listed everything that could go wrong, afraid I’d get screwed with a haunted house, timeshare, or property that didn’t exist.

But it was Shangri-La. Space! Trees! Water! Cooler, fresher air. Lovely rustic chic decor. The opposite of Schitt’s Creek. I felt like my fellow Midwesterner Madonna in Desperately Seeking Susan, the black-clad bohemian mesmerized by suburbia, luxuriating fully clothed in an empty Jacuzzi. Alice—whose city apartment had only a bathtub in the kitchen, like my parents’ Lower East Side childhood homes—took multiple daily showers. The TV remote was too complex so we didn’t watch the news, almost forgetting the virus for a New York minute.

The third night, my husband’s sister and her boyfriend, Steve, picked up Chinese food to eat outside, asking, “What else should we bring?” We said, “laundry detergent” and “bug spray”—things we hadn’t thought to bring. They taught us to use the washer and dryer, disposal, garage door, and thermostat—things city mice didn’t usually need to master. Steve gallantly returned a slimy slug to the backyard.

The next morning, we discovered a deli that delivered bagels, plus The New York Times and Post. Charlie was able to see his mom once outside—she was thankfully feeling better. Alice, who figured out the fancy coffeemaker, was a great swimming companion. Charlie even jumped in.

There was only one problem he and I didn’t anticipate: regret. We were joyous in the kind of house we couldn’t wait to escape. “This was the life we were supposed to live,” Charlie lamented, sitting in the sunroom, overlooking the water. “Am I a failure for not giving it to you?”

Charlie’s old haunts were just miles from the plush residence we were trying on for size. Was it a trick our late fathers were playing on us this late in our lives? Though we had no kids or grandkids to fill the spare bedrooms, he asked, “Did we make a mistake? What if COVID lasts? We could move here. Should we have been here all along?”

We weren’t alone in asking. The pandemic sparked an exodus of frantic Big Apple residents permanently fleeing the city for the burbs, an estimated 420,000 from March to May, buying up even unwanted homes long on the market. I could see why. Just one hour away, we could get twice the space for less than what we paid in the city, with lovely water views.

Yet my husband had trouble navigating the steep wooden staircase leading to the main bedroom, where the sun shone so brightly through the shutters that it woke us every day at 7 a.m. The house creaked with country noises. We fended off mosquitoes and ticks, grossed out to hear if we put garbage outside the wrong day, animals would eat it. We felt far away from civilization. We needed a car to get to the CVS (instead of walking to one of the four drugstores in our Manhattan hood). It was too quiet. Our weeklong experiment was relaxing and wonderful. Yet by day five we missed the steamy, noisy, half-deserted crazy city we’d never give up on.

The best solution was to buy a summer house, which we couldn’t afford. But if we kept working hard, we might manage to rent the house another week. Freud said the life forces were work and love. We realized how lucky we were to be alive, working and in love. And like our parents, we’d learned: Wherever we sheltered together was home.

Susan Shapiro, a Manhattan writing professor, is author of several books her family hates like Barbie: Sixty Years of Inspiration, Five Men Who Broke My Heart, The Forgiveness Tour, and her writing guide, The Book Bible. Follow her on Twitter at @Susanshapironet and Instagram at @profsue123.