Bubby and Birnbaum

A once-acclaimed author of essential prayer books—and my grandmother’s friend—belatedly gets the gravestone he deserves

On a bright October afternoon, my husband and I joined a group from Manhattan’s Jewish Center synagogue for an unusual memorial event at the vast Sharon Gardens cemetery in Valhalla, New York: the gravestone rededication ceremony for once-acclaimed prayer book author Dr. Philip Birnbaum, whose 1988 New York Times obituary described him as the “most obscure best-selling author.” Birnbaum, who wrote the groundbreaking Siddur Ha-Shalem, was a member of the Jewish Center for the last several decades of his life, but according to most people, kept to himself and usually said “no, thank you,” to invitations for Shabbat meals.

Yet even though only a few here knew him, about 15 showed up in person at the rededication and many others joined on Zoom—whether out of respect for a scholar, community obligation, or chesed shel emet, the act of performing a final kindness for a deceased individual. It also mirrored the influence that Birnbaum had on my life and others after his death.

Although I never knew Birnbaum, I heard his name mentioned frequently and in reverential tones throughout my Wilmington, Delaware, childhood—especially by Bubby, my grandmother, a Hebrew-school teacher who studied with Birnbaum and was one of the original members of the Hug Ivri, a Hebrew-speaking group that Birnbaum founded in January 1946, and of which my 93-year-old mother is still a member. By most recent reports, it is the oldest continuing gathering of its kind in the United States.

It was during his 20-year stint in Wilmington, where Birnbaum headed the Associated Hebrew School, that he published both his Siddur-Ha-Shalem and a High Holiday prayer book (machzor); decades later, they often remain the go-to prayer books for some traditionally observant Jews. According to a Wilmington News Journal article at the time of the siddur’s 1949 publication, Birnbaum himself was amazed at the reception that Siddur Ha-Shalem received. However, it was no surprise that Bubby was one of Birnbaum’s most ardent admirers both during his time in Wilmington and after he moved to New York in 1963. An aspiring Judaic scholar who also wrote fan letters to rabbis, Bubby was in awe of Birnbaum’s brilliance as well as his passion for using precise and proper language, whether in Hebrew, English, or Yiddish.

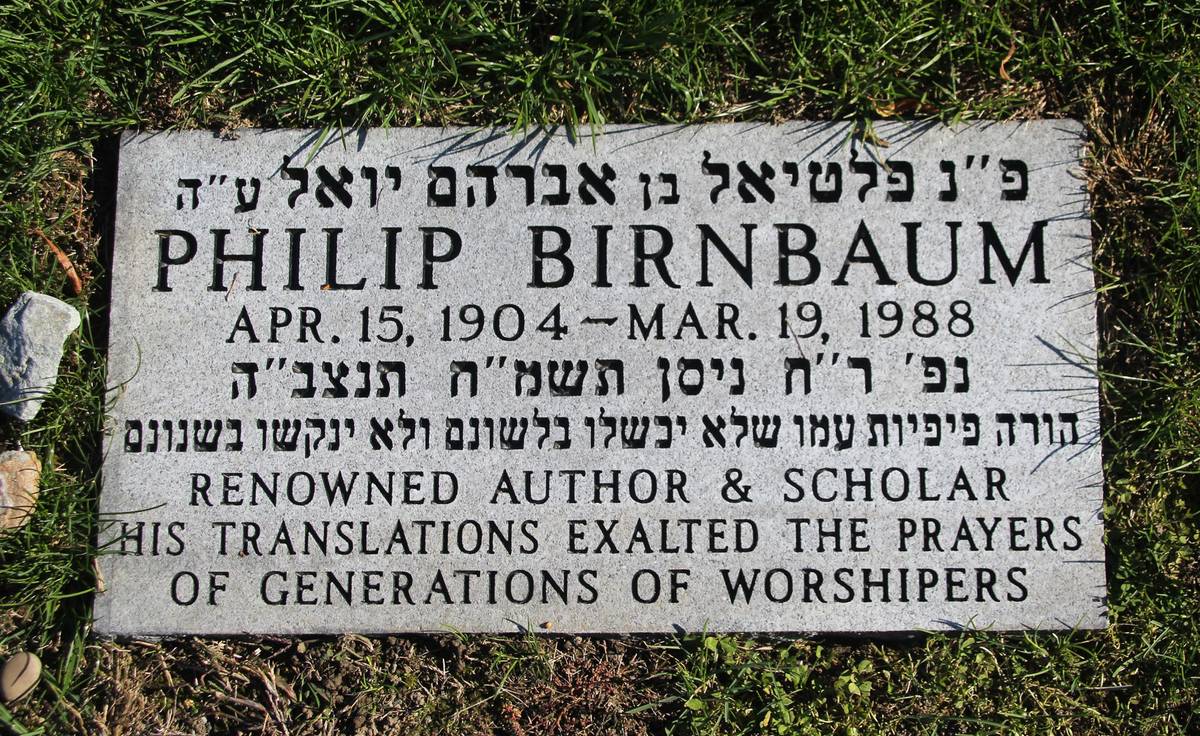

So, I believe she would have been appalled to learn that, until four months ago, Birnbaum’s gravestone featured a spelling error in his first name (Phillip rather than Philip), an incorrect birth year (1905 rather than 1904), and another spelling error in his description (“a renouned author”). But I also have no doubt that she would be pleased that, thanks to the diligence and persistence of a young Maryland lawyer, writer, and Yeshiva University graduate named Yosef Lindell, Birnbaum has finally gotten a more fitting headstone, which is the reason that we gathered in October.

Bubby may have wondered how these mistakes were made. Or she may have understood why it happened that an unmarried man with no children, or close relatives living in the United States, had no one to properly weigh in on or vet his gravestone either at the time of the first unveiling or on subsequent visits to the cemetery.

Which helps explain why it took 34 years for this gravestone rededication to occur and only after Lindell, who had been doing research on Birnbaum’s prayer books and other works, discovered the problem from a photo he’d seen on Twitter. After noting both the errors and the absence of any Hebrew text on the gravestone, he decided to take action.

As Lindell tells it, he reached out first to his YU mentor, Rabbi J.J. Schacter, a senior scholar and professor of Jewish history and Jewish thought at YU, and then to Rabbi Yosie Levine, the current rabbi of the Jewish Center, who put him in touch with former Jewish Center President Larry Kobrin.

With Kobrin, who is also a lawyer, Lindell checked court files and searched other records so that they could move ahead to change the stone. Eventually, they did discover the name of the executor of Birnbaum’s will, who is also long deceased. With the help of a genealogist, Lindell eventually got the name of a nephew in Israel, but it took a while to track him down and make contact with his family.

Replacing a headstone can be a long, drawn-out process, but Kobrin was able to raise the funds within only a few weeks from Jewish Center members who had known Birnbaum. “It was relatively easy,” Kobrin told me.

Kobrin also planned the day’s tribute, which consisted of the memorial service at the cemetery, followed by a Zoom presentation at the Jewish Center, given by Lindell, for a larger crowd of synagogue members and others.

Before coming, I wondered how this unveiling might differ from others I’ve attended, most recently for my uncle, who had himself claimed (true or not) that he had helped Birnbaum edit his siddur.

But this memorial service for Birnbaum followed the same format as others, albeit with the participation of revered and eminent rabbis. That day, near Birnbaum’s gravestone, the service began with remarks by Rabbi Levine, who made a cogent point about community standing in for family and then introduced Rabbi Schacter as “moreinu rabbeinu” (our teacher, our rabbi).

After reciting the customary Psalm 23, Rabbi Schacter asked Lindell, his former student, to formally uncover the gravestone, lauding him for “your dogged determination, your incredible interest, your focus, your undying commitment to see this happen.” He also quoted various Jewish sages on how it only takes one person to make a “massive difference.”

“Yosef taught us and continues to teach us what one person can do,” said Schacter.

Schacter, who became rabbi of the Jewish Center in 1981, related a story about being worried about Birnbaum’s reaction during Schacter’s “tryout Shabbos”: “He was, for me, from the distance, a forbidding figure. He was extremely famous, sat two rows in front of Dr. Lamm,” Schacter said. “I tried very hard not to look over there. So, I looked over at Larry’s friendly happy face and felt comfortable,” Schacter continued, referring to Kobrin, and we in the crowd chuckled.

Schacter told us he was relieved to hear, from the shul president, that Birnbaum had said his speech was “amazing.” “I think that’s what sealed it for me, if I got the gushpanka [seal of approval] from Dr. Birnbaum, must be that it was a good sermon.”

Lindell, the final speaker, told the crowd what drove him to correct the gravestone and the genesis for his research on Birnbaum, which stemmed from discovering that Birnbaum’s 1951 High Holiday prayer book was still in use at the synagogues where he led services. “If my research taught me anything, it’s that Dr. Birnbaum cared deeply for the Hebrew language. And he cared deeply about accuracy,” said Lindell.

In describing his quest to correct the errors, Lindell said he also felt compelled to add a Hebrew verse from the High Holiday prayers, but one that would be in keeping with Birnbaum’s opinions that inscriptions on grave markers should be modest: “He instructed the mouths of his nation so that their tongues should not falter and that they should not err in their language or falter in their speech.”

Like Lindell, I think Birnbaum would have approved of this verse, as well as have been gratified that such a bright and learned young man as Lindell was the driving force in correcting and replacing his monument.

Perhaps Birnbaum would also have approved of this short and modest ceremony, which like other traditional unveilings, ended with a group Kaddish and the Kel Maleh prayer.

Later, I would attend Lindell’s presentation and find out more about “the man behind the machzor,” as Lindell characterized him—but in the quiet of the cemetery, I just wanted to meditate on my own decades-overdue gratitude to Birnbaum and for what he imparted to my family and my hometown. I wondered if he, like my beloved childhood rabbi, Leonard Gewirtz, of blessed memory, also made it a mission to heighten Jewish learning and observance in Wilmington’s small Jewish community.

But I have no doubt that it was Birnbaum’s influence that led Bubby to stuff me with lessons in Hebrew, the Five Books of Moses, and Ethics of the Fathers (Pirkei Avot), in addition to roast chicken, noodles, and apple cake—at weekly lunches at her house throughout my elementary school years.

A woman rich in opinions, Bubby may have also taken issue with the characterization of Birnbaum as an “obscure author.” However, Birnbaum himself may have been less concerned with name recognition than what people could glean from his prayer books and other works, including a Haggadah, an Encyclopedia of Jewish Concepts, The Concise Jewish Bible, as well as his own version of Pirkei Avot.

As Lindell told me, “I get the sense from what Birnbaum writes, that he wasn’t looking for fame. He was looking to educate people.”

Marla Brown Fogelman is a freelance writer in New York City. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Parents, The Forward, Moment, and other national and regional publications.