Buddhist Temples Seek a New Path to Combat Anti-Asian Violence

In the wake of vandalism and assaults, religious leaders draw on their own history, as well as alliances with other denominations

When a 60-year-old Vietnamese man was sucker-punched while walking in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood in March of this year, a defunct coalition of local clergy was resurrected: Uptown Clergy came back together to organize the Uptown Rally Against AAPI Racism on May 2 in the parking lot of the Buddhist Temple of Chicago.

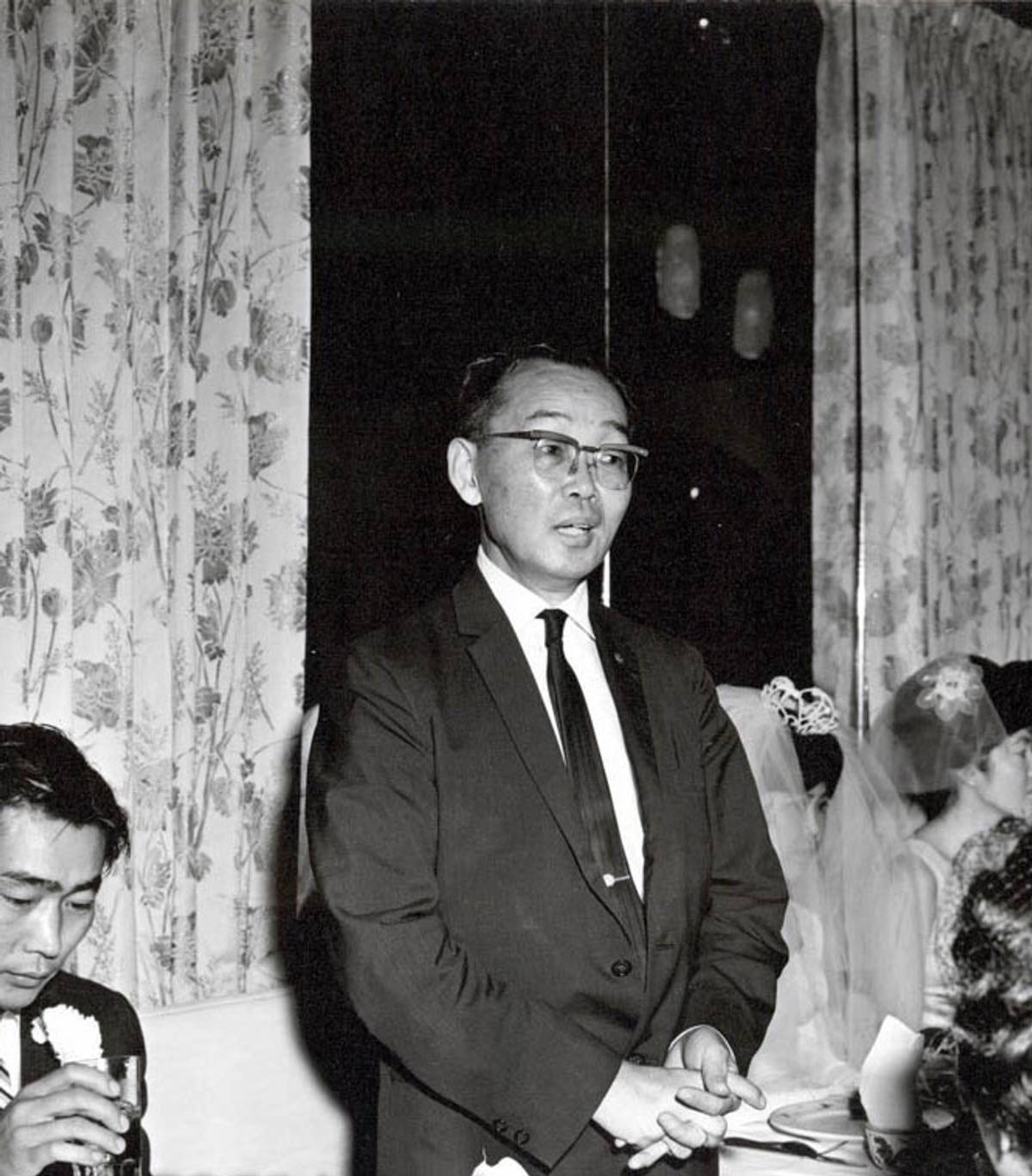

The Buddhist Temple of Chicago is, in many ways, an intuitive place to address rising anti-Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) violence; its history is bound up with earlier waves of racial and ethnic bias. Founded in October 1944 by the Rev. Gyomay M. Kubose after he spent two years in a Wyoming Japanese American internment camp, the Buddhist Temple of Chicago took on a place of central social and religious importance to the Japanese Americans coming from internment camps in the western part of the country around that time. It is a legacy literally enshrined in its original altar, an ornate piece of craftsmanship made out of scrap wood by a detainee at Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming.

While temple today is no longer the city’s hub of Japanese American cultural activities that it was for much of the latter half of the 20th century, it stands athwart the current wave of xenophobia, amid a recent nationwide increase of Buddhist temples as targets for vandalism from California to Arkansas—where the Bible-toting Shawn Michael Israel destroyed a Buddhist statue with a hammer, telling authorities it was a “false idol.” The Chicago temple also shares a denominational link with the Higashi Hongaji Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles, which was recently the focus of national media attention after it, too, fell victim to vandalism.

When the Rev. Patti Nakai of the Buddhist Temple of Chicago addressed the attendees on May 2—along with Ravenswood Fellowship United Methodist Church’s Pastor Ji Eun “Mori” O and Illinois state Sen. Mike Simmons—the rally was at once distinctly Buddhist and uniquely American. “We do belong here,” Nakai said in her remarks. “We’re not others. We’re not foreigners. We’re here as fellow Americans.”

Duncan Williams, professor of religion and East Asian languages and cultures and the director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, said that during WWII, the U.S. government started to recognize that two-thirds of the people they were holding in internment camps were U.S. citizens who hadn’t been charged with any crime, nor granted due process. With two looming Supreme Court cases on the matter, in late 1943 and into 1944 the government began to release detainees who could pass a loyalty questionnaire. Religion was a key part of the test: Respondents received two additional points for identifying their religion as Christian. Buddhists were docked a point. Shinto respondents were banned from release altogether.

Chicago was a popular destination, Williams said, because the departing detainees were younger, so they were able to obtain permission to study at colleges and universities, as well as get jobs, with the help of letters of recommendation and employment verification from sympathetic organizations, such as those with Quaker affiliation. The government also promoted places in the Midwest due to the sparsity of Japanese communities in the region, Williams said, out of fear of raising tensions in places with already extant Japanese American populations. And that’s how Kubose came to found the temple in 1944.

The Buddhist Temple of Chicago holds a service on Sunday mornings—a practice temple president Bill Bohlman said is a legacy of Japanese immigrant leadership trying to assimilate in the early part of the 20th century by mimicking mainline Protestant denominations.

“I always say American Buddhism is a combination of cultural adaptation and bringing something innovative to the American religious landscape,” Williams said. The cultural cross-pollination that was already influencing Japanese American Buddhist practices—calling temples “churches,” referring to priests as ministers, the use of hymnals—was accelerated by a perceived need to appear nonthreatening with the onset of WWII, he said.

Today, there is little evidence of mid-20th-century Uptown, which was populated by a mix of Japanese Americans from California and poor white migrants from Appalachia, who also began coming to Chicago in the wake of WWII. (One board member who grew up attending the temple with his family said he remembers shoeless Appalachian kids attending flea markets at the Buddhist Temple looking for new clothes.) The Uptown neighborhood is still a distinct mix, albeit of the kind that often typifies gentrification, where million-dollar condos exist alongside rehab centers, psychiatric hospitals, and affordable housing facilities. Indeed, the Chicago Department of Public Health has a site offering behavioral health and addiction services for the homeless close to the temple.

Like the neighborhood, the character of the temple has also changed. Although it has flyers for Japanese cultural activities, including weekly on-site Aikido classes, the temple today is multiethnic, with its literature characterizing the temple’s mission as making “Buddhism available to all by presenting the teachings in Western terminology.” A temple member attributes the changing ethnic character to the younger generations of Japanese Americans moving out to the suburbs and disaffiliating from Buddhism. The Buddhist Temple of Chicago evolved with less of an entrenched Japanese community than the kind enjoyed by the still-predominantly Japanese American Buddhist temples on the West Coast, where some temples are more than a century old, or in Hawaii. Plus, with a higher rate of what he calls “ethnic out-marriage,” Williams said, “Those temples, to survive, have been much more, let’s say, welcoming, of people of different ethnic backgrounds.”

American Buddhism is a combination of cultural adaptation and bringing something innovative to the American religious landscape.

“It’s not that people are unwelcoming on the West Coast,” he said with a laugh, “but because it’s had this longer, over a hundred-year history of being tied to one ethnicity.” He said it’s only in recent times that the Japanese American population has become more multiracial. Williams said he believes the 2020 census will show about 50% of the roughly 1.3 million Japanese Americans are of multiracial background, adding: “I would say a lot more so in places like Chicago and New York.”

Uptown Clergy used to meet monthly for an informal lunch—but that eventually fizzled out when its members moved on. But People’s Church of Chicago pastor Rev. Rudra Dundzila helped resurrect it when he identified a need for a community response to the March attack in Chicago: “I got in touch with the other churches in the area and I said, ‘What can we do?’”

Pastor Mori’s Christian congregation at Ravenswood Fellowship UMC still includes members who were among the 110,000 to 120,000 Japanese Americans held in U.S. internment camps during WWII, as well as veterans. Mori holds Sunday morning services a half a mile away from the Buddhist Temple of Chicago, in a stately late-19th-century stone church at the end of a shady tree-lined street of Victorian homes. Tidy lawns and windows are festooned with signage bearing rainbows, declaring Black Lives Matter, and boasting of admission to or graduation from selective prep schools. Down the street is another Uptown Clergy-affiliated church, the Catholic Our Lady of Lourdes. At sister parish St. Mary of the Lake, the priest addresses his Saturday night vigil Mass homily to a small, multiethnic, mostly older congregation, including references to the Montgomery bus boycott and to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and concluding with an encouragement for the congregation to discern how they are being called to make a difference in their community.

Originally from South Korea herself, Mori said it was the March attack on the Vietnamese man that led her to join the Uptown Clergy group when she learned it was planning a rally against anti-AAPI racism. “This is not just Atlanta,” Mori said she remembers thinking, referring to an attack on a spa in March that left eight dead. The Chicago Police Department said that no arrest has been made in the attack on the Vietnamese man at this time and the investigation is ongoing—and as of July, the prosecutor and district attorney involved in the Atlanta case asserted the attacker in the spa shootings was not racially motivated.

A group of around 10 Uptown faith leaders, including Nakai and Mori, resolved to organize a May rally against Asian hate in recognition of Asian American/Pacific Heritage Month. Around 100 attendees at the rally received outsize media attention thanks to some members’ connections at the Archdiocese of Chicago, Dundzila said. “Hopefully the media coverage let other parts of the city know that there is movement, that there is action.”

Uptown Clergy is now meeting regularly again with new faces and sense of purpose. “Right now we’re meeting in relationship,” Dundzila said, “getting the dialogue going and developing a relationship with the Asian community that we serve—because about 10% or 14% of this neighborhood’s population is Asian American and they’re very much underrepresented in all the communities of faith.”

Earlier this year, on the evening of Feb. 25, the Higashi Honganji Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles experienced vandalism during an online board meeting.

Like the Buddhist Temple of Chicago, Higashi Honganji Temple also follows the teachings belonging to the sect of Jodo Shinshu. Founded in the 13th century by Shinran, a former Buddhist monk, it is focused on opening the heart and mind to connection with the other “uncountable lives” on earth—not just human, but in the natural world, as well. Eventually splitting into Eastern and Western factions, Higashi (Eastern) Honganji is the smaller of the two in the U.S., with only around a dozen temples, while Nishi (Western) Honganji has nearly 10 times as many.

Higashi Honganji head priest Bishop Noriaki Ito said his assistant showed him the damage via Facetime after hearing the noise: lanterns toppled and lantern stands set on fire; a large panel of glass shattered. No one was physically harmed.

“It happened right around the time that all of these crimes against Asians were happening. People assumed that this was another incident of hate crime,” said Ito. As a result, he said, the temple received a lot of national and international media attention. “I felt like the whole story was overblown,” he said, “because of the fact that it was right in the midst of that time. When we actually processed what the damage was, it really wasn’t that big.”

Ito said he was asked to give a presentation to the LA County Board of Supervisors along with other Asian Americans who had experienced verbal and physical attacks and discrimination. “Listening to their stories,” he said, “I realized what we experienced was very minor.”

“At the same time,” Ito said, “We did feel an obligation to get involved, and so we started partnering with community organizations to get the word out,” an effort that included the distribution of leaflets with reporting information for witnesses of attacks and coordinating self-defense classes for senior citizens.

Crucially, their response included reaching out to other Buddhist denominations as well as other religious faith communities. It culminated in a service called "May We Gather,” held at the Higashi Honganji Temple on May 4 and organized by Duncan Williams, along with Funie Hsu and Chenxing Han.

“May We Gather” occurred 49 days after the Atlanta spa shootings. “The 49th day is important in our tradition,” said Ito. “Although we don’t talk about what happens to us after we die [...] we say that the 49th day is when the deceased becomes a Buddha, and by becoming a Buddha, it’s not like in any kind of mystical way, you know, like they’re out there somewhere, it’s just more in terms of being a teacher, because you know, the Buddha was our teacher, and our parents, our grandparents who passed away become our teacher and put us on a good path for the rest of our lives.”

Ito said they invited all of the ethnic Buddhist communities in the Los Angeles area to the ceremony, resulting in a total of 49 priests from Chinese, Korean, Tibetan, Japanese, Sri Lankan, and Thai Buddhist traditions. “May We Gather” incorporated chanting, dharma talks (analogous to sermons), and symbolic rituals from a variety of cultural traditions.

“It was really the first time that we got together as a Buddhist community, of Buddhists from all over the Asian countries, the first time that we met each other,” said Ito. He was approached by someone who said, “‘Reverend Ito, we need to do this a lot more regularly.’” Ito mentioned potential future interdenominational events, perhaps of an educational nature. He also said they received an “outpouring of support” from Christian and other faith communities.

“We’re all human beings trying to live together,” said Ito.

Like the temple in LA, the Buddhist Temple of Chicago has also witnessed some recent vandalism: boulders moved in the parking lot, a stray bullet from a drive-by shooting captured on a surveillance camera. But the Rev. Nakai said, “I don’t believe any of those events are anti-Asian hate crimes.”

Nakai and Ito’s apparent downplaying of their own temples’ vandalism doesn’t mean the nationwide spike isn’t real; after all, they both helped carry out rallies in support of Asian communities. More likely, their attitudes reflect an indication of the nuanced and complicated nature of the problem, as well as the approach many Buddhist groups are taking.

When asked how Buddhists in America can effectively counter anti-AAPI violence and bigotry, Williams, who is also a Buddhist priest, said Buddhism’s “only goal” is the alleviation of suffering: physical, mental, spiritual. “Whatever we need to do to lessen it,” he said, “that’s what we should be engaged in.”

According to Williams, Buddhism offers two main ways to “break the cycle of suffering”: first, moving out of ignorance to wisdom through the shifting of perspective—not just yours but your country, your neighborhood, your workplace—and second, compassion.

“Usually we think we are alone, or we act in a way that’s self-centered,” Williams said. “The Buddha taught that when we can see we are, our lives are, interlinked and intertwined with each other and that, in fact, your own freedom and liberation can’t come without the liberation of [...] not just even human beings, but all sentient beings, that everybody becomes free.”

This view is echoed by San Francisco State Asian American studies professor Russell Jeung, of Stop AAPI Hate, an advocacy organization dedicated to tracking attacks on Asian Americans. “Sadly, some journalists have to grab attention-seeking violent crime that now seems to portray Asians as victims, and others as perpetrators,” he said in an interview with NBC earlier this year. “We would appreciate stories that tell more of the context about the individuals and the broader social, underlying factors that lead to a crime or racism.”

“Faith-based communities are crucial in changing [the Asians-as-perpetual-foreigner] narratives in the U.S.,” Jeung told me in an email. “They have ethics of hospitality and inclusivity, of treating each other with dignity and respect. And by working together across faith tradition, they can demonstrate what solidarity and fellowship looks like to our divided nation.”

If data suggest that the issue of anti-AAPI violence and bigotry resists facile narratives about white supremacy or COVID-19 restrictions, the same appears true of the solutions.

“The life of freedom and liberation not only can’t be done alone but sometimes can’t be done in a simple, kind of easy way,” said Williams. “Sometimes it takes effort and time and collaboration, solidarity. But also, it also takes sometimes generations. Especially the types of suffering that we think of when we think about racialized violence and exclusion in the United States. It was not something that happened suddenly, but it’s things that have endured and have found different ways to manifest.”

“We can do the immediate things, because that’s important, too,” Williams said. When it comes to the long term, he speaks of a wounded intergenerational spirit: “The karma of not just an individual but of a community or a nation, we have a kind of racial karma that has had some hurt and you know, difficulty associated with whatever your ethnic background in America, it doesn’t matter whether you’re Black, or white, or Asian, or whatever [...] we inherit the karma of our ancestors, those who’ve come before us, whether we like it or not.”

The targeting happened not just because they were Asian, but because they were Buddhist, and has to do with this kind of bigger idea about who belongs in America, and what is American identity if it’s not white and Christian.

The societal tendency, Williams said, is to focus primarily on the targets of violence and exclusion, whereas “actually, those who are conducting that may also actually have a racial karma that they’ve kind of hung onto and [...] that needs to shift and change, too. It’s actually a project for everyone.”

If Williams is right, the old cliche, “history doesn’t repeat itself but it sometimes rhymes,” appears to be bearing out for Asian Americans in the 2020s. At the time of the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, religion was used as a scare tactic, as exemplified by Bret Harte’s poem “The Heathen Chinee,” a “group of people racially unassimilable and religious unacceptable to what it meant to be American,” Williams said. “Starting from that era to incarceration [...] during WWII, that is in a long lineage of what’s been happening in Asian American history, and so when we talk about, kind of, COVID-19 era rise or spike in anti-Asian violence, it doesn’t take much to see the parallels in sundown towns in California, lynching of dozens of Chinese miners in Wyoming. There’s so many incidents of violence and exclusion baked into the history of Asian America that it’s hard to say this is new.”

“The targeting happened,” Williams said, “not just because they were Asian, but because they were Buddhist, and has to do with this kind of bigger idea about who belongs in America, and what is American identity if it’s not white and Christian.”

“The WWII experience kind of sheds light on many different aspects of both pre-WWII and what’s been happening,” he said.

Zen Buddhist priest the Rev. Cristina Moon, who lives at the Rinzai Zen temple Daihonzan Chozen-ji in Honolulu, has written about younger Asians leaving their families’ Buddhist traditions behind out of a sense of alienation stemming from a perception that the faith made them seem foreign or different. However, her Buddhism informs her belief that connection and relationship can succeed where top-down policy initiatives might not.

Moon coordinates with community leaders to support the work of Hui Aloha, a grassroots organization aimed at eliminating silos to address issues surrounding unhoused populations.

“From a Zen Buddhist perspective,” Moon said, “it’s actually short-sighted to focus only on stopping anti-Asian violence. We need to aim farther, at transcending this sense of separation and dualism, of self and other. It’s a significant step forward that Asian Americans across the board are having wide ranging conversations about anti-Asian racism now, where it seemed like those conversations were previously only happening in small pockets. But Asian Americans can even defy the mainstream Western approach, drawing on Asian religions and cultures to fundamentally reevaluate the problem of racism, our goals vis-a-vis racism, and our strategies to transcend it.”

“May We Gather” and the Uptown Clergy initiative complement a Buddhist understanding of alleviating suffering and many Asian cultures’ practical approach to problem-solving. It is the slow work of listening and understanding in a collective context of communal interdependence, a process that can seem at odds with American cultural preferences for metrics, measurable outcomes, independence, and speedy results.

“When people talk about dismantling racism,” Moon said, “they often like to quote Audre Lorde: ‘The master’s tools cannot dismantle the master’s house.’ In Zen we have a similar saying, ‘You can’t wash away blood with blood,’ and it’s a bit more universal or transcendent. It means going beyond the dualistic delusions of having power and not having power, of oppressor and oppressed. It’s unfortunately not enough to dismantle the construct of racism with other, countervailing concepts like anti-racism. But if we are actually striving for something further beyond, then by necessity we’ll also overcome the things that hold us back, individually and collectively, whether that’s habits, trauma, or even racism.”

From the Higashi Honganji temple’s ceremony that brought together Buddhist temples from various sects and ethnicities—something that has hardly if ever been done before—to the way Buddhist groups have come together with local community stakeholders to raise awareness and address the root causes of violence and distrust, the characteristic that stands out is the importance of cultivating relationships.

Speaking recently with Yascha Mounk on the podcast "The Good Fight,” Princeton sociology professor Patrick Sharkey hypothesized that suffering and social atomization as a result of lockdown restrictions have contributed in part to the recent crime increase in U.S. cities, the broader context in which anti-AAPI violence is one facet.

Both his academic diagnosis and his prescription involve social trust, and do not differ much from those offered by Jeung, Williams, Ito, Mori, or Moon: “We now have decades of evidence from lots of really good ethnography work on the ground, causal analysis, and randomized control trials, telling us that [we need to] invest in core community organizations to provide high-quality after-school programs, to provide better lighting around housing developments, to clean up abandoned lots and restore abandoned buildings. Business improvement districts have a causal effect on violence. All of these kinds of programs, when you invest in them—and when people know that that organization is going to be here in 10 years [...] make a neighborhood stronger and make a neighborhood safer.”

Under these criteria, when it comes to an effective counter response to anti-Asian animus, Buddhism seems up to the challenge.

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.