‘You Can’t Outrun Trauma’

Stephen Mills’ new memoir details sexual abuse at a Jewish summer camp

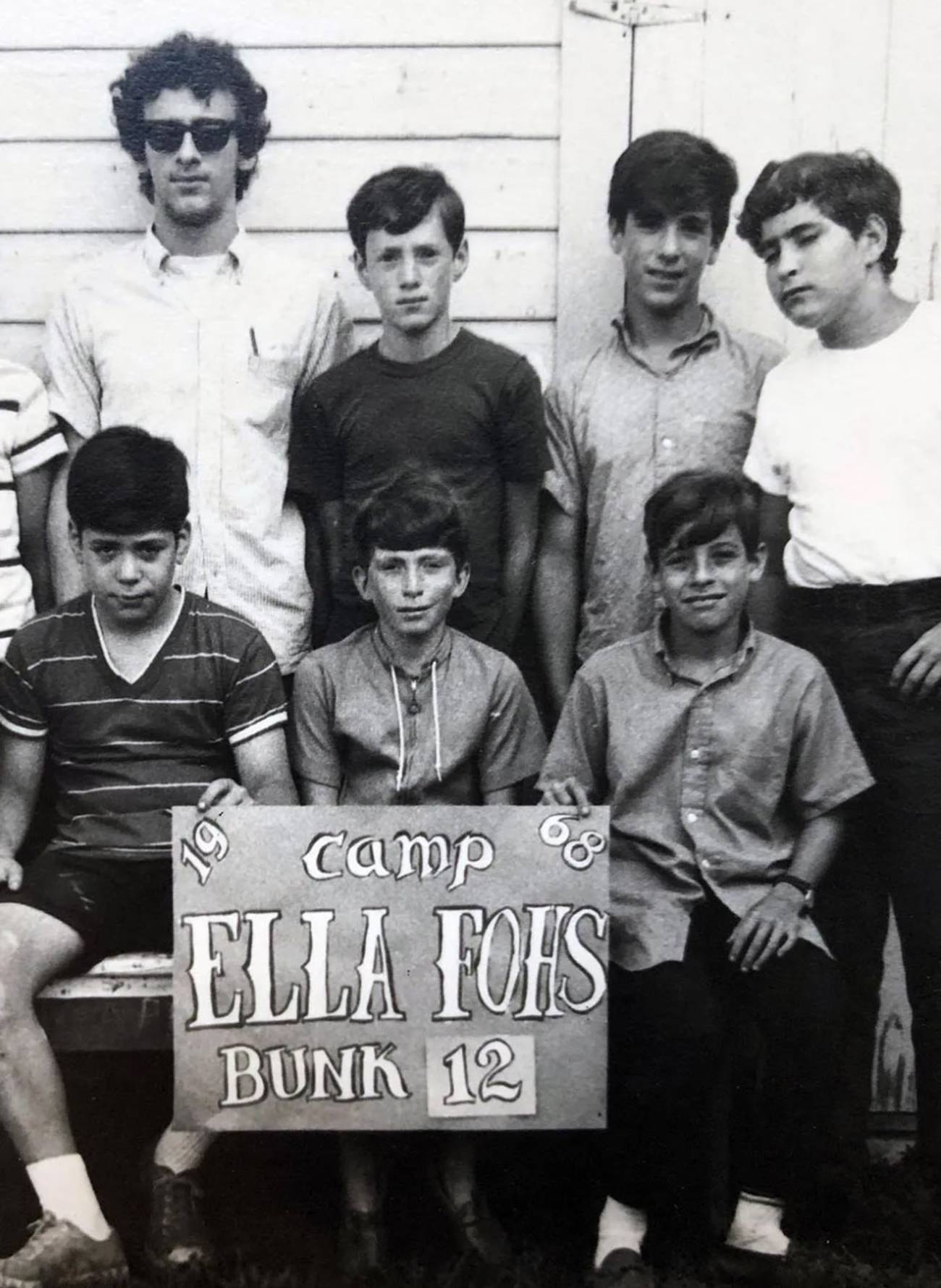

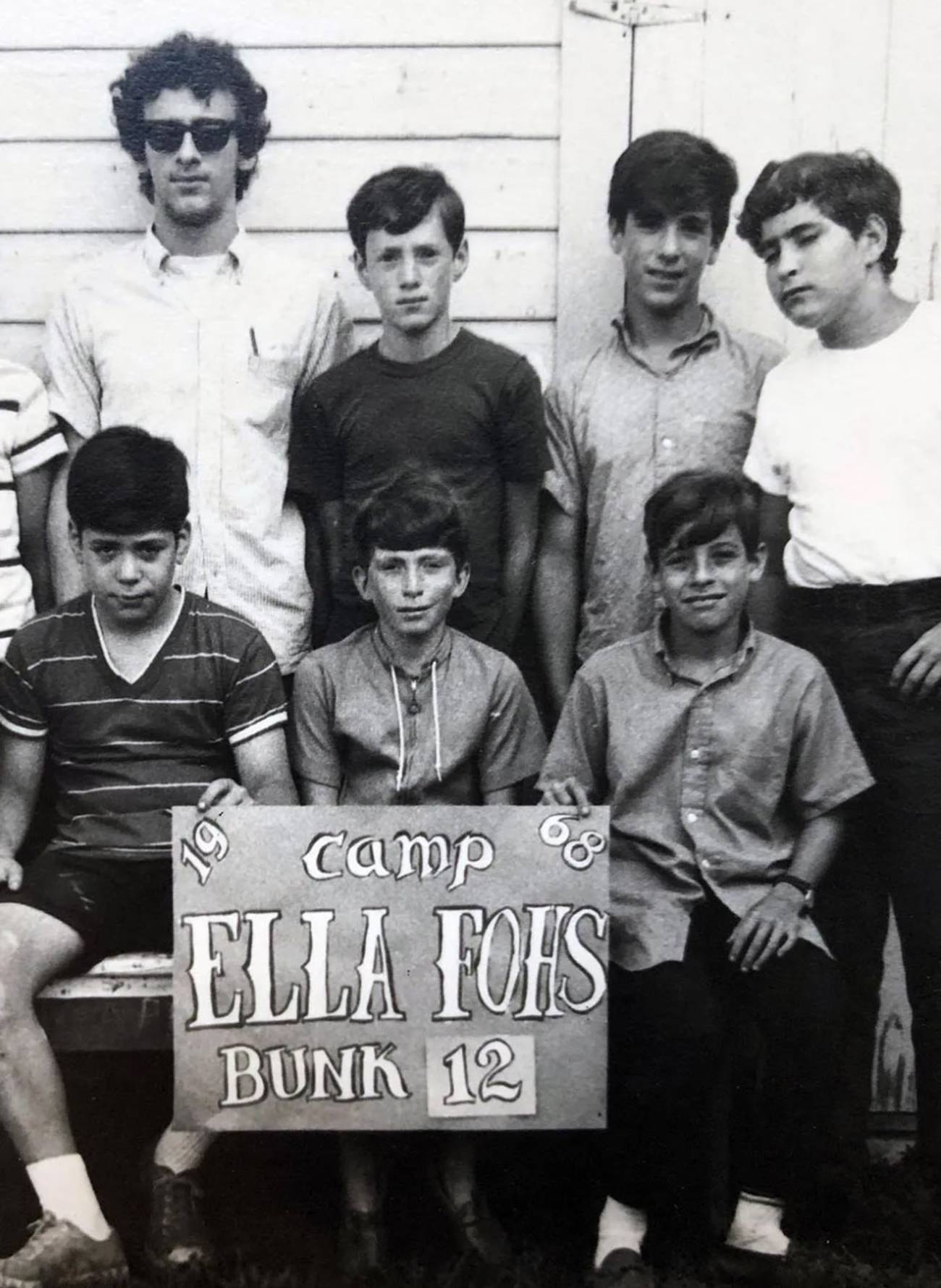

In the summer of 1968, 13-year-old Stephen Mills of East Meadow, Long Island, went to UJA-Federation’s Camp Ella Fohs, a coed sleepaway camp in New Milford, Connecticut, run by a charismatic social worker named Dan Farinella. “The first time I saw him I thought he might be Rodney Dangerfield’s Italian twin brother,” Mills writes in his new book, Chosen: A Memoir of Stolen Boyhood. “His dark basset-hound eyes and big lips gave him a perpetual hangdog look.”

Soon the half-Italian, half-Jewish Farinella, who loved “horsing around” with male campers down by the waterfront, was singling out Mills, who had lost his father at age 4, for special attention: long walks in the woods where he would ask him probing questions about his family, treats of milk and cookies in the director’s cabin.

But it wasn’t until the following fall, when Farinella invited Mills to spend an off-season weekend at camp to “help out with some projects there”—an invitation that felt to Mills like “winning a prize I didn’t know existed”—that the sexual abuse began. “I closed my eyes and prayed,” Mills writes of the first time that Farinella orally raped him. “I’m not here. I’m not here. When I opened my eyes, I was floating, looking down at my body, as if it belonged to someone else.”

Rabbi Ruth Sohn, who is director of both the Aronoff Rabbinic Mentoring Program and the Spirituality Initiative at Hebrew Union College in Los Angeles, overlapped with Mills at Camp Ella Fohs when she worked there as a counselor, at age 16, in the summer of 1970. Although she did not know Mills at the time, and never heard any allegations of abuse at the camp, she does distinctly remember Farinella, who was her boss. He had “a particular flavor of charismatic warmth,” she told me, “a sense of familiarity that may not have been earned … a way of kind of holding the space, owning the space, in a way that is disarming.”

The mission of the camp, said Sohn (who is, by marriage, a member of the family whose donated estate eventually became the camp’s property), was to help kids who were from “one way or another, disadvantaged backgrounds—campers who had lost a parent, campers whose parents were divorced, all sorts of issues—and that was wonderful.” But what was “highly problematic,” she said, was that Farinella hired counselors who were “themselves in need of healing experiences, counselors who had overcome serious drug problems.”

According to Mills, it was between 1968 and 1970 that Farinella repeatedly sexually abused him—whether at camp in Connecticut, on a Catskills trip for Jewish camp directors, or on Farinella’s own family’s vacation to the Bahamas on which Mills was an invited guest. The fact that Farinella would provide Mills with copies of Playboy to distract him while he abused him, and that he managed to forge an incredibly close-knit bond with Mills’ mother and stepfather, who began unwittingly inviting their son’s rapist to join in their family’s Jewish holiday celebrations, only further confused the young Mills who found the heavyset and muscular Farinella physically terrifying. “I didn’t say a word,” Mills told me. “I was sure this guy would kill me.”

As Mills grew from an adolescent into a teenager, Farinella began to resort to more explicit verbal manipulation in order to continue to abuse him. In his book, Mills recalls Farinella telling him one morning in the summer of 1970 in his “hideout,” a small room under the stairs in an old mansion on camp property:

In our society, we think there’s something wrong with sex between men. In ancient Greece they thought it was normal … Every man would choose a boy as his friend and lover … They got married and had families. But male friendship—that was the ideal.

“I tried to take this in,” Mills writes. “It did explain how [Farinella] could be married and still be attracted to a boy. The problem was, the boy in this Greek drama was me.”

Decades later, in 1986, when a 31-year-old Mills was finally able to confide in his parents about what Farinella had done to him, they were in shock, and found discussing the past with him—an experience that Mills felt was necessary—too fraught and difficult. Ultimately, however, by the time Mills was in his 50s, the three of them were able to address what happened. Mills’ parents asked for his forgiveness, he said—and he not only gave it, but was relieved to do so. Mills’ stepfather died in 2006, and his mother in 2009.

Now 66 years old, the married father of an adult son, and living in California, Mills is able to speak dispassionately of the abuse inflicted on him by Farinella, who died of throat cancer in 1993, but this wasn’t always the case. Sexual abuse, Mills told me, is “an instant shame that lasts a lifetime. For sexually abused men, the common pattern is numbing that shame, hiding it by drinking heavily, drugging heavily, acting out sexually in destructive ways, suicidal ideation or attempts at actual suicide.” Mills enacted all of these various responses over the course of his younger decades, and also suffered through panic attacks and poor physical health—experiences he chronicles unsparingly in Chosen.

The memoir also documents Mills’ quest to try and get the accountability that he is seeking from the multiple Jewish organizations that employed Farinella, who, over the course of his career, not only ran UJA’s Camp Ella Fohs, but also the YM-YWHA’s East Tremont Y in the Bronx; the Jewish Council for Youth Services’ Camp Henry Horner, outside Chicago; and the youth programs, as well as the Emma Kaufmann Overnight Camp, of the JCC Pittsburgh. “These are great institutions,” said Mills, who in 2021 filed a lawsuit against both UJA-Federation and the YM-YWHA, which ran Camp Ella Fohs, under the New York state Child Victims Act, which for one year removed the statute of limitations on childhood sexual abuse so that now-adult victims could file civil claims against their abusers and the institutions that employed them. (Due to COVID-19, that removal of the statute of limitations on child sex abuse was ultimately extended for a second year; it expired last summer.) “If I’m a parent,” said Mills, “and I have a kid in camp in any of these institutions, I want to know that they’re willing to get to the bottom of what happened with the case of a serial predator from 40 or 50 years ago because if they can’t do that now, how in the hell are they going to face up to, and do what needs to be done, if something happens this summer?” In late January, Mills’ attorneys submitted disclosure of his evidence and witnesses for his case. They are now awaiting a response from the UJA-Federation and YM-YWHA.

Back in 1986, after going through years of therapy, and with the support of his wife, Mills tried to build a criminal case against Farinella, who was then still working with children at the Pittsburgh JCC. Through his own Camp Ella Fohs network, Mills was able to locate multiple other victims of Farinella, including two victims—plus three corroborating witnesses—who gave him statements that he then presented to the district attorney in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (where the Pittsburgh JCC is located), and the prosecuting attorney in Morgantown, West Virginia (where Emma Kaufmann Camp is located). But in the end, and much to Mills’ profound disappointment, no criminal case was ever brought. The next year, Mills connected with an FBI agent in lower Manhattan, who told him: “The average molester abuses 117 kids in his life. We’re never going to change things until people wake up to how prevalent this is. Then the agencies and law enforcement and the courts will start changing. You’ve seen it all firsthand … Why don’t you tell your story?”

After decades of fits and starts, and even giving up completely, Mills found a new resolve to do so thanks to being inspired by those who came forward as part of the #MeToo movement, and also by Junot Diaz, whose New Yorker essay about his own childhood sexual abuse called “The Silence: The Legacy of Childhood Trauma” was published in April 2018. “Some switch flipped,” said Mills, “and that same week I started writing and I couldn’t turn it off.”

That project complete, Mills is now turning his attention to what he says is the lack of a survivor-run platform in mainstream Judaism for those, like him, who have been sexually abused from within. The Catholic Church, he points out, has SNAP, the Survivors Network of Those Abused by Priests, and U.S. Athletics has Army of Survivors for child athlete survivors of sexual violence. But in Judaism, he says, there is mainly just Za’akah, for survivors of child sexual abuse within the Orthodox community, and a small group run out of Israel called VoiCSA, Voice Against Child Sexual Abuse, which advocates for survivors globally.

“There has to be a process established that gives survivors a voice while protecting their identities, and gives them a seat at the table for how better protections are going to be implemented going forward,” said Mills. “We’ve got to repair the community. It’s all about tikkun.”

Johanna Berkman is an investigative journalist who has been writing a series for Air Mail about sexual abuse at the all-boys, and largely Jewish, Brant Lake Camp in upstate New York.