The Changing Face of the Rabbinate

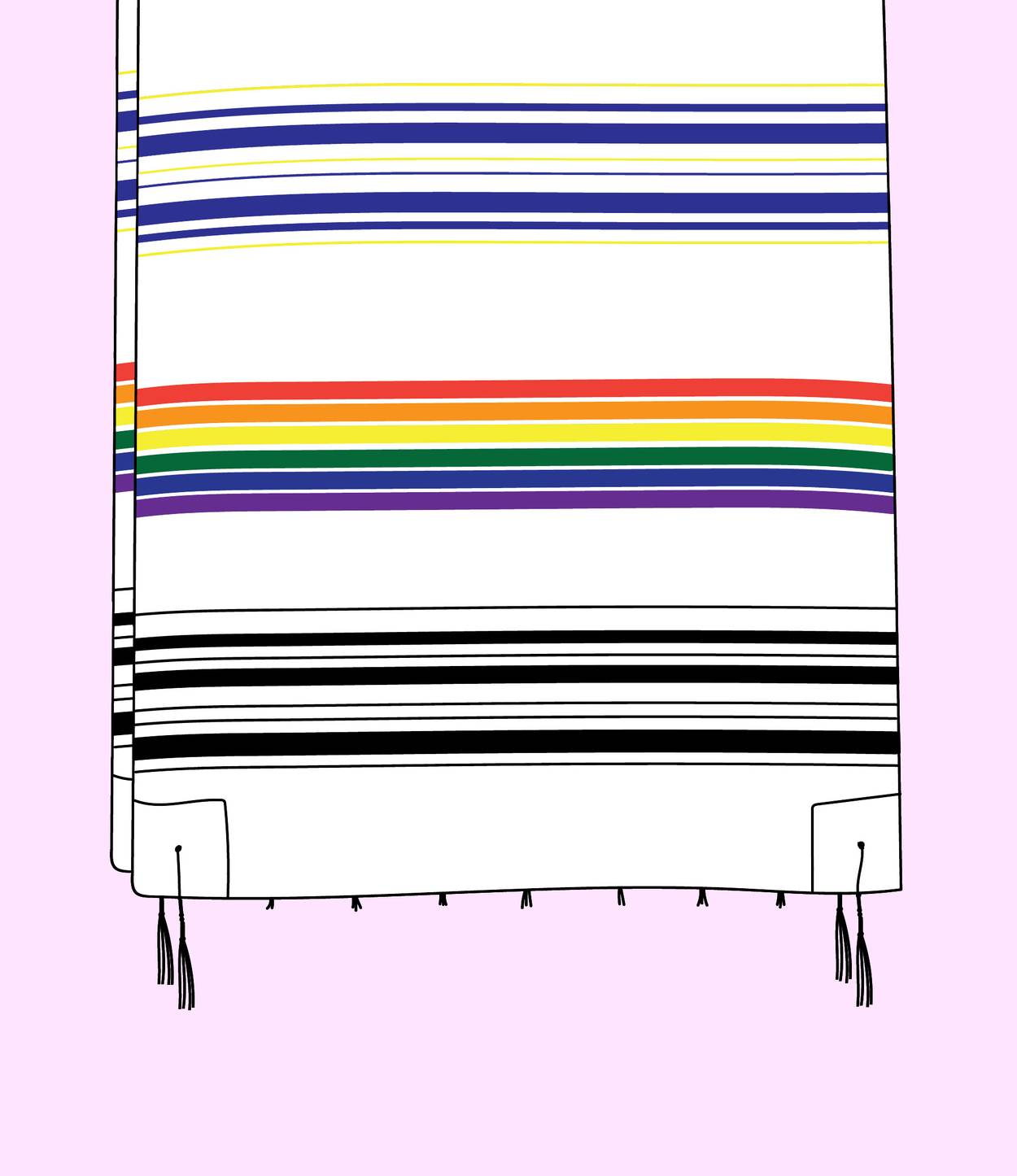

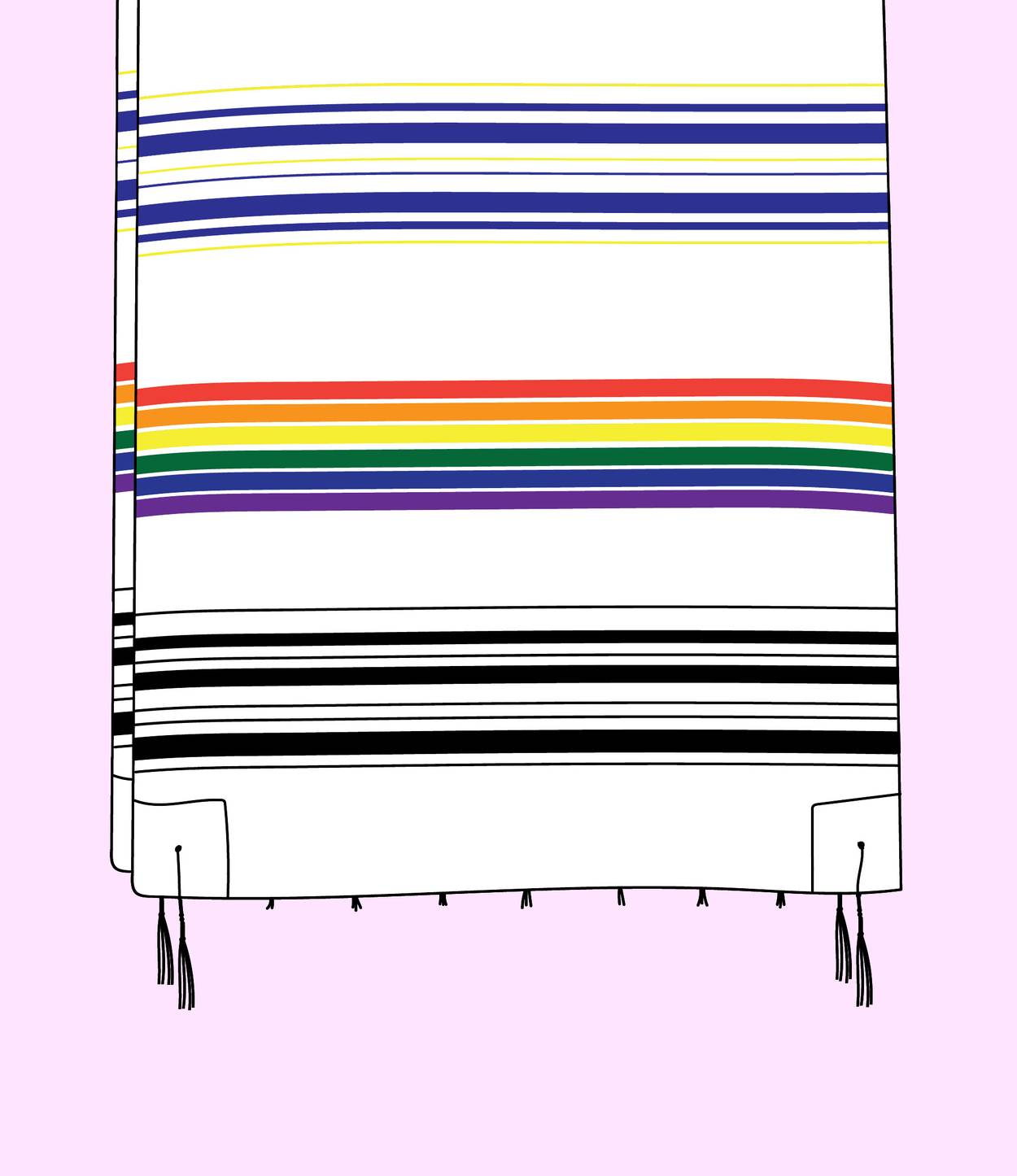

As more Orthodox women, LGBTQI Jews, and people of color get ordained, rabbis reflect an increasingly diverse community

Rabbi Sandra Lawson had endured a grueling process of applying and interviewing for many jobs at many different inclusive synagogues but had not yet been successful. However, after months of hard work, her final application really felt promising. As she edged closer to the finishing line, Lawson began seeing herself in the role she had applied for. As a queer, Black convert who had served in the military before being ordained through the Reconstructionist movement, she was used to shattering expectations of what “Jewish clergy” looked like. However, the job was not to happen; the synagogue—which was presenting as inclusive and open-minded—informed Lawson, she said, that they ultimately “could not hire a Black rabbi.”

This was the last straw for Lawson. “I only apply to progressive places, and when the last congregation I applied to would not hire me, I was angry, hurt, and frustrated,” she said. “If I couldn’t get a job there because people couldn’t get over my color, who was going to hire me?” With the feelings still fresh from this rejection, Lawson founded a community organization called Kol HaPanim. “I wanted to create a community that speaks to people of color,” she said, “so that it normalizes people of color being rabbis and cantors in the Jewish community.”

This organization is helping to break down stigma and runs community-focused activities, including monthly Shabbat services and events, as well as activities led by people, like Lawson, who identify as Jewish people of color. “Most of my congregants are not Black, but they are going to hear a Black, Asian, or brown person leading service,” Lawson said, “and this will help make it become normalized in the Jewish community and help to reduce racism, as their expectation of what a Jewish rabbi looks like changes.” In January 2021, she was also named the first director of racial diversity, equity and inclusion in the Reconstructionist movement, a newly created position, in an attempt to help the movement become an “anti-racist organization and movement.”

Lawson is part of a new wave of rabbis coming from diverse backgrounds and actively helping to change the perception of what an American rabbi looks like. In the past decade there has been a monumental shift, with the establishment of Orthodox female rabbinical schools as well as greater interest and enrolments in many rabbinical schools from traditionally marginalized communities, including Jewish people of color and members of the LGBTQI communities. Many of these students and rabbis are helping to educate people on the diversity of the Jewish community, by being appointed into positions of leadership. As a result of these new faces joining the rabbinate, the rabbinate is becoming increasingly diverse. “Judaism has evolved over the centuries,” said Lawson. “As our society becomes more accepting of queer people and newer faces entering the rabbinate [like Orthodox women] and more members of the LGBQTI community, you will see greater representation in leadership because the American Jewish community accepts these people as leaders.”

Among North American clergy students, perhaps one of the best known rabbinic fellowships is the Wexner Graduate Fellowship/Davidson Scholars Program, which provides a generous financial stipend, mentorship opportunities, and an alumni list that has included some of America’s most prominent rabbis. This year, the 33rd cohort of the fellowship reflected the increasing diversity of the American rabbinate. Out a total of 16 fellows, at least six belong to emerging groups that symbolize the diversity of people joining the rabbinate, namely: Orthodox women, Jewish people of color, and members of the LGBQTI communities.

Jericho Vincent, a 2021 Wexner recipient who identifies as nonbinary, preferring the pronouns them and they, is a writer and lecturer. Vincent has enrolled in Aleph, the Jewish Renewal rabbinical school, and thinks that the diversity of people seeking careers in the rabbinate is a natural shift. “Some people seem to have a hard time acknowledging it, but the Jewish community is varied and are made up of many different segments,” they said. “There are Jewish people of color; there are Jews who are members of the LGBTQI community; certainly not all people identify as cisgender males.”

The trend may be recent, Vincent said, but it has “ancient” roots: “The Jewish community has never been homogenous; we have written different sects and people out of the mainstream narratives—they never made it into the canon,” they said. “Today, as part of the new wave of rabbis joining the rabbinate from diverse backgrounds we are coalescing and growing stronger and doing a tikkun. We are saying it is our inheritance and we all have a right and responsibility to engage with Judaism.”

According to Vincent, who has just completed their first year of rabbinical school, “it is an exciting time to be joining the rabbinate, as people are stepping up to fill the gaps of representation in our community; many of our people need spiritual leadership and these new voices emerging have firsthand exposure to many of the issues that will affect their congregants.”

As one of the new Wexner fellows, Vincent will enjoy activities with a supportive cohort of rabbinical students. Stefanie Zelkind, the director of the fellowship, believes that this year’s selection process was particularly competitive, with an especially large and diverse applicant pool: “The fellows’ commitment to exercising leadership in the North American Jewish community is, we believe, a cause for hope and optimism at a time when we need it more than ever.”

Another emerging area reflecting the shift in the American rabbinate is the increase in women seeking out careers as Orthodox female rabbis. When Yeshivat Maharat was founded in 2009, with the ordination of Rabba Sara Hurwitz, there was fierce backlash from some segments of the Orthodox community but also a growing sense of excitement that new roles for Orthodox women seeking positions as clergy were finally beginning in a new era. Rabba Rachel Kohl Finegold was part of the inaugural class of ordained women that graduated from Yeshivat Maharat in 2013. Today she works at Congregation Shaar Hashomayim in Montreal, where she gives classes and sermons, officiates life cycle events, and offers spiritual care, in addition to being responsible for all youth and education programs at the synagogue.

“The arrival of women in these religious leadership roles has been made possible by a confluence of factors,” Kohl Finegold said, “the gradual opening of doors to deep text learning, the many manifestations of female Orthodox leadership that has grown over the past many decades, the encouragement of male allies, and the boldness of women being willing to see themselves in these roles even though they never saw other women in them before.” When Kohl Finegold entered the rabbinate there were fewer than 10 ordained Orthodox women globally. These days, the number is closer to 100.

Her rabbinical school, Yeshivat Maharat, allows graduates to pick their own titles, with many opting for rabbanit or rabba. Kohl Finegold said that while she originally opted to be called maharat (an acronym created in 2009 to denote female spiritual leadership), she changed her title over time to become rabba, the feminine version of rabbi in Hebrew, as, according to her, “the title maharat was confusing to some people.”

“Once I changed my title and became rabba, I think my role in the clergy became clarified,” Kohl Finegold said. “The fact that the title sounds rabbinic helps allay some of the confusion around whether my training was the same as our senior rabbi and whether my ritual roles could be the same as any other Orthodox rabbi—it can be—even while I don’t sign a ketubah or lead services in the minyan, I fulfill all the same rabbinic duties as my male colleague does.”

In contrast, Rabbi Eryn London, a 2017 Yeshivat Maharat graduate, has almost exclusively used the title rabbi since her ordination: “For the first year after smicha [ordination] I said I would use the title rabbi in the hospital where I worked as a chaplain and in most communities where I would teach or lecture, I told them they could use rabba or rabbi.”

But London soon changed her mind as she found that she preferred to use the title rabbi in all professional capacities: “That is what my job is, it’s what my title is, I don’t think its gendered, in the grand scheme it denotes a seriousness of study,” London noted. “Any title that you use opens or closes doors and it depends on which doors you choose to keep open what title you use. And anyways, any places that are not comfortable with me using the title rabbi are not places that I want to work in.”

Another rabbi reflecting the changing faces of the American rabbinate is Mike Moskowitz. Ordained in ultra-Orthodox yeshivas in Israel and America, Moskowitz still dresses in traditional Haredi rabbinic garb, complete with a black hat and beard. He held a variety of roles in the Orthodox community including synagogue and campus rabbi and worked as a classroom rebbe and Talmud teacher in an ultra-Orthodox community. However, he started speaking out in favor of LGBTQI and trans rights when someone close to him transitioned. The pushback from his Haredi community was swift: He lost his job and livelihood. For a while he was even unemployed before he was appointed as the scholar-in-residence for trans and queer Jewish studies at Congregation Beit Simchat Torah, a nondenominational LGBQTI synagogue in New York.

Moskowitz says that due to his unique background and affiliation with the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community, as well as his activism on behalf of transgender and LGBTQI Jews he attracts people from ultra-Orthodox communities who find him with their questions. “A lot of ultra-Orthodox guys who are struggling with their gender and sexual identity reach out to me to ask advice,” he said. “I also receive ‘off-the-record’ referrals from ultra-Orthodox rabbis and even rosh yeshivas from Haredi communities—the rabbis reach out and ask if they can send people, often young boys who are struggling with sexual or gender identity to me.”

According to Moskowitz, “it turns out, lots of young people who are exploring their gender identity or sexuality have similar questions to straight people: They just need to feel safe and be able to find someone they can trust to advise them on relationships and dating.”

For Lawson, creating Kol HaPanim has been a cathartic experience. Her group is active on different social media platforms and she undertook a fellowship through Hillel’s Center for Rabbinic Innovation to further develop the organization. Lawson thinks it’s important that her initiative is publicized widely on the internet. “We have found out that things live on the internet forever, they never really truly go away,” she said. “Because of the internet, more people are finding Judaism or finding things representing Jews from diverse backgrounds, which I think is great.”

For now, Kol HaPanim will be running monthly Kabbalat Shabbat services, currently on Zoom due to the pandemic, but hopefully in-person soon. This past month the Shabbat service was led by May Ye, a Chinese American Jewish cantor. In Lawson’s words: “How cool is that? She’s going to lead Shabbat services! For people saying they can never see a person with her background in that role, they will now be seeing a person with a diverse background in that role, and because of the internet, it will be there forever, so in the future if anyone is looking to find someone in the Jewish community that looks similar to them, they now can!”

Nomi Kaltmann is Tablet magazine’s Australian correspondent. Follow her on Twitter @NomiKal.