Chasing the Hindu Vote

Virginia’s recent gubernatorial election put a spotlight on the community, and how its political leanings are being shaped

Barely a week after Virginia’s gubernatorial elections in November, campaign signs were still ubiquitous as I traveled in and around Loudoun County. Thanks to controversy around culture wars in its schools, the county—part of D.C.’s northern Virginia suburbs—had been front and center in media coverage of the election, but Loudoun’s demographics were largely overlooked by reporters. Asians are the area’s second largest racial/ethnic group, after whites. During their campaigns, both incumbent Terry McAuliffe and Governor-elect Glenn Youngkin reached out to Hindu community leaders as part of their effort to reach Asian American voters. And though Hindu Americans may not have been the electoral tipping point for Youngkin, a potential partisan shift toward the GOP among this predominantly immigrant group may signal a broader national electoral shift.

While Indian Americans tend to identify as Democrats, when preference is broken out by religion and immigration status, the picture changes slightly. According to Utsav Chakrabarti of the policy research group HinduPACT, the rise of identity politics in the U.S. complicates things for Indian Americans, since identitarianism can be perceived as placing precedence on skin color and country of origin over beliefs and values. But Chakrabarti favors breaking out Hindu Americans as a group distinct from the category of Indian Americans or Southeast Asians, since he said some Hindu Americans may feel that being categorized with other South Asians can be problematic due to ethnic and religious tensions.

The data seems to bear that out: Whereas 82% of Muslims in the Carnegie Endowment’s recent Indian American Attitudes Survey said that they planned to vote for President Biden in the 2020 elections, only 67% of Hindus did. Data from the IAAS also appears to bolster Chakrabarti’s characterization of the Hindu American experience as fundamentally an immigrant one. According to the survey, naturalized Indian Americans who have been in the U.S. more than a decade preferred Biden, whereas those who have arrived in the past decade showed stronger support for Trump. While naturalized Indian Americans in the IAAS survey were still less likely as a whole to vote and have weaker partisan affiliation compared to U.S.-born Indian Americans, Chakrabarti thinks this is changing, especially among Hindu Americans.

Suhag Shukla, executive director of the Hindu American Foundation, said in an email that in her anecdotal experience, she has seen an increase in the number of Indian Americans getting involved in electoral politics “from canvassing to contributing.”

It can be difficult to break out numbers on Hindu Americans specifically, but an article on the Loudoun County website says India is the main country of origin for county residents born out of the country (1 in 4 Loudouners, according to the article).

“A little over half of the total 4.6 million people of Indian descent/origin are eligible to vote,” Shukla said, which accounts for less than 1% of all eligible voters. She also said that “we extrapolate to calculate the Hindu population” from among Indian Asians in the census numbers, since around 80% of Indians in India are Hindu. “This may seem miniscule. However, concentrations of Indian Americans are growing rapidly in many swing states. More importantly, Indian Americans actually go out and vote: 97% of eligible voters surveyed in the 2020 Asian American Voter Survey responded to their plans to vote; 84% reported that they were absolutely certain they would vote in the state election. When elections are being won and lost by such slim margins, this is untapped and reliable potential that is really available to both parties and independents.”

Loudoun County ranks tech among its top industries, in the areas of information, communications, and data centers, as well as in health analytics and information. Chakrabarti says these occupations, as well as the area’s biomedical industry, have attracted Hindu Americans to the area. It’s a number that’s been rising steadily. A 2016 Loudoun Times-Mirror article said the same, and described the 20,000 to 25,000 Indian Americans living there as “becoming more actively involved in the social, community, education and cultural aspects of life.” From the 2010 census to the 2020 census, Loudoun County’s population increased over 30%, and the Asian population increased even more, from 46,033 to 89,779, now accounting for more than 20% of the population.

“Most of them,” said Chakrabarti of Hindu immigrants, “came to America because they wanted to excel on the basis of their hard work and their skills.” He said this focus is something that comes from Hindu values of self-reliance and the ideas that “you are responsible for your own growth and success,” and of “focusing on the self and trying to make yourself better.” According to Chakrabarti, Hindu Americans “don’t like handouts.”

Of course, Hinduism may not have a specific prohibition against handouts, but it does list artha among its four main pursuits. A Sanskrit word for wealth or property, artha is not an end in itself, but rather a condition of a sort of spiritual hierarchy of needs in order to pursue the other three aims: dharma (duty), kama (love), and release from the recurring cycle of birth and death (moksha). Inordinate attachment to wealth, however, is to be avoided.

While I was in Loudoun County, a friend said he was told by an employee that the hotel where we were staying was a popular destination for Indian weddings. When I asked a local who worked in the area, they said that dual-culture weddings were common, and a traditional Hindu ceremony was often accompanied by an additional, more typically American-style celebration.

Similarly blending cultures, the Mudra Arts Center has locations in Loudoun County, and its website offers Diwali discounts and classes in Hindu values and religious texts, as well as videos of a 4th of July performance and a Southern Indian-style dance set to “Jingle Bell Rock.” “I’m an American citizen,” said founder Chander Vanjani. “I’m proud to be.”

Vanjani came to the U.S. decades ago to work in IT, before switching to television production. He founded the Mudra Arts Center around 15 years ago out of a desire to serve his community, and describes it as a “labor of love.”

Vanjani said that while Hindu American young people speak English and get involved in all the typical American extracurricular activities, their parents still want them to know their language and culture, since visits back to India every couple years are common. Mudra offers classes in classical dance and music forms from India that are thousands of years old. Vanjani said the conventional wisdom is that the discipline that comes with studying Indian classical art forms—as opposed to taking Bollywood dance classes, which he said are becoming more popular—can help improve academic grades.

Echoing Chakrabarti, Vanjani said there is a cultural emphasis on education and hard work, with Hindu parents’ “highest priority” being education, followed by career success, with a focus on IT, finance, and medicine. He said Loudoun County is the ultimate destination along northern Virginia’s Data Center Alley for Indians coming from universities once they have children, due to the reputation of its schools. Loudoun County public schools boast the Academies of Loudoun, which are made up of an Academy of Engineering and Technology, an Academy of Science, and the Monroe Advanced Technical Academy.

The number of Hindus in northern Virginia has grown in recent years—a rough estimate of Hindus of Indian American descent alone is over 200,000 in Virginia and Maryland according to Shukla. However, Americans’ first significant encounter with Hinduism dates further back, the result of 19th-century ecumenical crosscurrents.

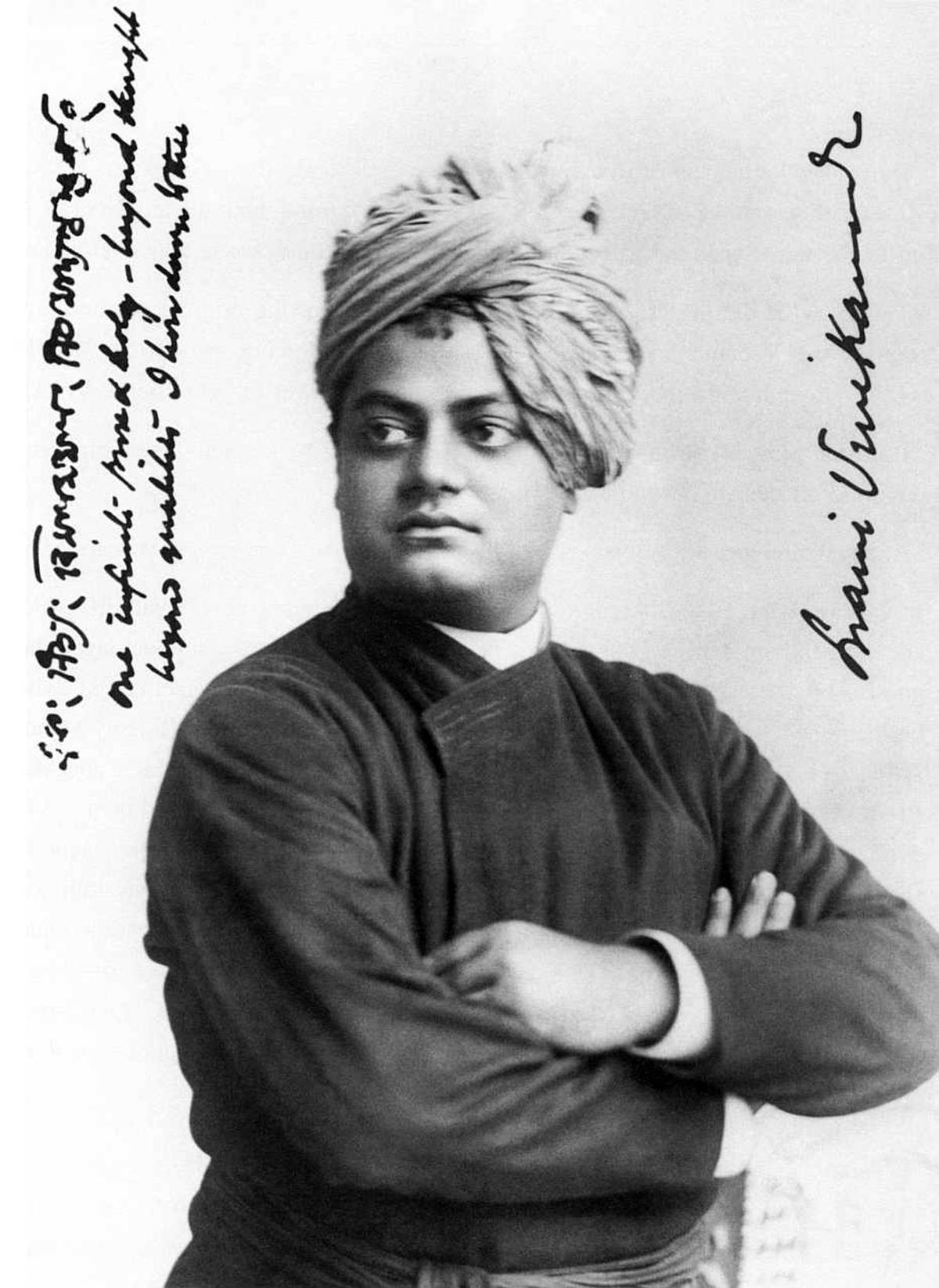

The visit of Swami Vivekananda to the Chicago World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893 is commonly considered the inauguration of Hinduism in America. Vivekananda was a Hindu monk from Calcutta who had received a Western-style education, rising to prominence in India and abroad with a message of service to others and social reform. Vivekananda espoused a philosophy of Hinduism known as Vedanta, and adapted it to his own time with a practically applied worldview that upheld service to others as service to God.

This is untapped and reliable potential that is really available to both parties and independents.

Vedanta is one of six schools of Hindu thought, and has within it its own branches. Meaning the “end” or the apogee of the Vedas themselves, it broadly upholds the agency and divinity of the self. The 19th-century Hindu social reformer Ram Mohan Roy was an early proponent of a distinctly contemporary kind of Vedanta, having been influenced by progressive Christianity, especially Unitarianism. He denounced the caste system and sought to diminish what he considered to be more superstitious practices through a movement he led known as Brahmo Samaj. The overlap of Vedantism with 19th-century liberal mainline Protestantism may also be detected in Vivekananda’s popularity with American Unitarians and Universalists.

Vivekananda’s remarks at the Chicago conference, an assembly of representatives of world religions, gave a quick primer of his view on the ancient nature of Hinduism, stressing the belief that all religions are true, and gave historic examples of religious tolerance extended by Hindu peoples to refugees fleeing religious persecution. He also pleaded for religious tolerance.

“I fervently hope,” Vivekananda said to the assembled faiths, “that the bell that tolled this morning in honor of this convention may be the death knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or with the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.”

Vivekananda’s system has been described in academic terms as neo-Hinduism or as neo-Vedantism. However, its four yogas (spiritual characteristics of selfless service, devotion, meditation, and knowledge, that can lead to spiritual liberation from the recurring cycle of death and rebirth), are consistent with the other schools of Hinduism, which all value deeds, compassion, and multiple spiritual paths to the divine. Vivekananda’s universalist conception of “different streams” all leading to the same God, and its accompanying focus on social service, enjoyed popularity with India’s educated classes, and it formed the model that Americans most commonly associated with Hinduism. The arrival of various gurus and immigrants from other Hindu nations beginning in the latter half of the 20th century helped spread other varieties. Indeed, Sekhar Tiwari of the American Hindu Coalition said that the children of white parents who got into Hinduism in the 1960s are, in his opinion, “much more staunch Hindus” than those who come from India.

Nevertheless, it is a photograph of Vivekananda at the World Parliament of Religions that appears on the website for the American Hindu Coalition, a D.C.-based nonprofit and political advocacy organization that aims to build “a stronger America through Hindu Enlightenment Principles,” and which endorsed Youngkin. These principles, they claim, began to take root in the American consciousness through John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, distilling the essential teachings of the Bhagavat Gita, one of the holy writings of Hinduism:

God is one creator of all universal sphere, without beginning, without end. God governs all the creation by his eternal designs. Search not the essence and the nature of the eternal, who is one; your research will be vain presumptions. It is enough that, day by day, and night by night, you adore his power, his wisdom and his goodness, in his works. The eternal willed in the fullness of time, to communicate of his essence and of his splendor to beings capable of perceiving it. They as yet existed not. The eternal willed and they were.

For all that, however, the AHC insists it is not a faith-based organization. “I have no religion,” said chairman Sekhar Tiwari. “I’m a Hindu.” Tiwari said the concept of religion is more European, and because Hindu religious texts are multidisciplinary, containing concepts like trigonometry, astronomy, algebra, physics, and chemistry, Hinduism is so all-encompassing as to transcend a set of beliefs and dogmas. Hinduism’s sacred texts, the Vedas, exerted influence over Nikola Tesla, Werner Heisenberg, and Robert Oppenheimer, and Tiwari told me this is why Hindu kids tend to be very good at STEM. Whether or not this is accurate, Tiwari feels the cultural emphasis among Hindus on the value of education contributed to the GOP’s inroads with their community during the Virginia gubernatorial campaign, in which the issue of education was front and center.

If I don’t go to temple, I’m a Hindu, nobody throws me out.

This focus on talent and effort may strike a false note with some in the Hindu community, who believe caste privilege back in India can translate into unfair advantage in the U.S., since certain castes are afforded more opportunities with regard to education and travel than others. The Indian constitution officially outlaws discrimination based on the Hindu caste system, which hierarchically separates individuals into one of four groups based on their place in society, from the priestly Brahmin caste of teachers, down to the lowest “untouchable” order, the Dalits. But the influence of this millennia-old practice can be seen to persist in polling, anecdotes, and lawsuits alleging caste discrimination in the U.S.

By contrast, Vanjani said Hinduism is “not very stringent,” with temple attendance not being a requirement, and filling a social rather than religious role for most Hindu Americans, with attendance limited primarily to festivals. “If I don’t go to temple,” said Tiwari, “I’m a Hindu, nobody throws me out.” A couple of Hindu Americans with whom I spoke casually mentioned attending Christian churches, in one case saying that they enjoy listening to the pastor, and also that the church puts on a good breakfast.

All the same, both the Democratic and Republican candidates visited Virginia’s Hindu temples. “He went to all the Hindu temples,” Tiwari said of Youngkin, adding that the governor-elect was received “very well.” Describing him repeatedly as “humble,” Tiwari said Youngkin “listened deeply.” A transition aide for the governor-elect confirmed on background that Youngkin visited a Hindu Temple, as well as an Indian Independence Day celebration, “speaking out on issues such as academic excellence and lowering costs of living for Virginians.”

While Tiwari said McAuliffe also visited Hindu temples in the state, he described a “stark contrast” with Youngkin.” Tiwari said that although McAuliffe “knew Hindu Americans more than Glenn Youngkin did,” he said the incumbent seemed primarily interested in defending his policy record.

Although the AHC itself is nonpartisan, Tiwari said almost 65% of Hindu voters in northern Virginia are Democrats (with the rest being Republicans and Independents), but he thinks an overwhelming majority of them voted for Youngkin, the GOP candidate. “Women especially,” he said, because they were worried about their children’s education.

The “make-or-break issue,” according to Tiwari, that caused Hindu voters to throw their support behind Youngkin, was the furor over Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology altering its admission standards in the name of expanding diversity. The school’s famously rigorous standards made it both famous and infamous in the area and in education circles.

“Merit was very important to us,” Tiwari said. “So when we saw that at Thomas Jefferson High School, the current government of Virginia is reducing the standard in the name of diversity, they want kids from other minority communities to also attend this school—I can see their motives, they want to uplift people—but what do we do? Where do the people who really are talented, hardworking go?”

It’s possible Loudoun County’s Hindu voters may one day form the crest of a nationwide wave. “Many Indian American parents were activated,” said Shukla. “I only see this spreading to other states, especially given the importance placed on education in so many Hindu American households.” The GOP seems to hope so. This past November, the Republican National Committee opened a community center in Dallas as part of its outreach to Indian and Asian Americans. The opening ceremony included a Hindu priest, a Diwali candle-lighting, and speakers’ referencing the recent Virginia electoral upset.

Hindus for Trump notwithstanding, if some Hindu American voters are switching to the GOP, a massive change could still be a long way off. After all, Loudoun County still went for McAuliffe in the end. Its voters sent Democrat Suhas Subramanyam to the state’s General Assembly, the first Hindu American ever elected, who in 2020 was sworn in using the Bhagavad Gita. However, as America looks ahead to the 2022 midterms, the values and priorities of Hindu voters who did back the GOP candidate in Virginia could still prove to be something of a bellwether.

For one thing, Hindus are not deeply involved in the abortion wars. (“We are more close to Democrats on that one,” said Tiwari, a Republican. “We believe the woman chooses what to do.”) Abortion was far from a motivating factor among Virginia voters, who cited jobs, the economy, and education among their top issues.

Shukla said Hindu Americans care about a “broad range” of issues that are “not that different from all Americans,” citing the economy, as well as “health care, immigration, and foreign policy—specifically U.S.-India relations.”

Tiwari, Vanjani, and Chakrabarti all described Hindus as pragmatists who put merit-based academic and career success at the fore. Similarly, electoral prognosticators looking to read the tea leaves in Virginia are predicting a midterm election cycle where voters may well prove to be motivated primarily by tangible concerns like the impact of inflation, their children’s education, and the COVID-19 pandemic. Those Hindus who shift their support to candidates promising to address those issues in tangible ways, as Chakrabarti and Tiwari think many did in Virginia, may mean they are simply with the majority of American voters, if current polling that suggests gains for the Republicans proves accurate.

It would mean Hindu Americans voting in concert with the majority of their fellow citizens. There is “something beautiful” about “this concept of melting pot,” said Tiwari. He noted that Hindu names can be difficult to pronounce, yet Hindu-raised Bobby Jindal and Indian American Nikki Haley went on to be governors in former KKK strongholds. (Haley was actually raised Sikh, and both Jindal and Haley are converts to Christianity.) “What has made this country a beautiful place for us? Merit. Hard work.”

Like other immigrant populations before them, Hindu American voters like Sekhar Tiwari may have an optimism about this country that some of their fellow voters, who have been here longer, no longer share.

“We look brown,” said Tiwari. “We had accent[s], we knew we were not born in this country. But in a period of 10, 15 years we became a CEO of a large company. Why? Because there is something inherent about this country that if you work hard, if you focus, and dream—dream comes true. They reward capability, merit, intelligence, knowledge. That is what took us to where we are.”

This story is part of a series Tablet is publishing to promote religious literacy across different religious communities, supported by a grant from the Arthur Vining Davis Foundations.

Maggie Phillips is a freelance writer and former Tablet Journalism Fellow.