In Columbus, Kosher Shoppers Can’t Fill Their Carts

Even as the Jewish population grows in Ohio’s capital, grocery options shrink for the kashrut-observant

After Bexley Kosher Market—at the time, the only kosher meat market and deli in Columbus, Ohio—closed in 2008, the Kroger supermarket in Whitehall, about 10 minutes from the large Jewish population center of Bexley, stepped in to serve kosher shoppers. It wasn’t the city’s only outlet for kosher food; two Trader Joe’s sell limited amounts of fresh kosher meat, the Jewish Community Center has a kosher kitchen with a small carryout operation, the Ohio State Hillel has a small kosher cafe, and there’s one preeminent kosher caterer. But the community relied on Kroger to fill in all sorts of gaps: The supermarket has a kosher bakery, a fresh deli, prepared foods, and frozen foods—and it became the prime destination for kosher-for-Passover food in Columbus.

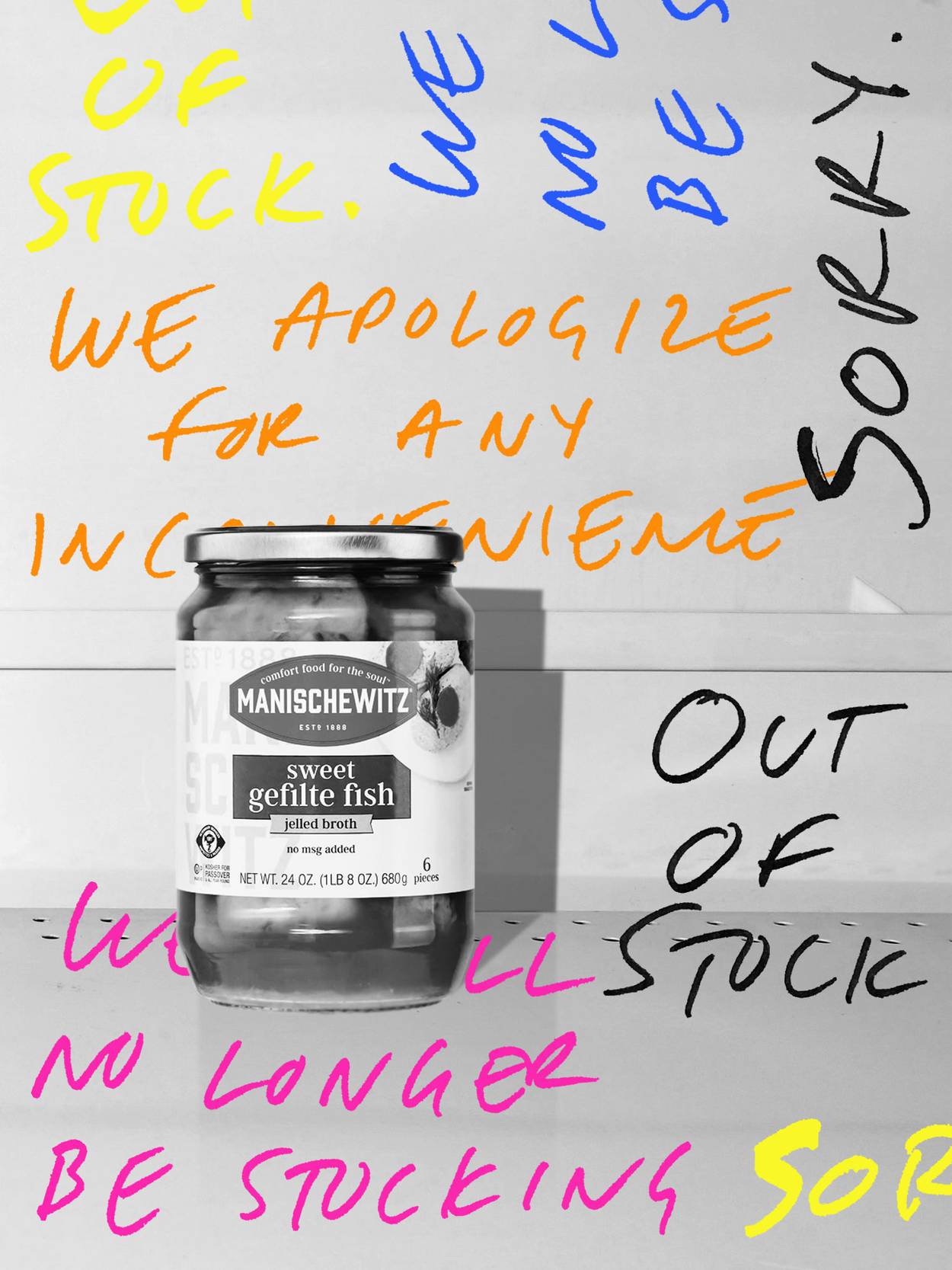

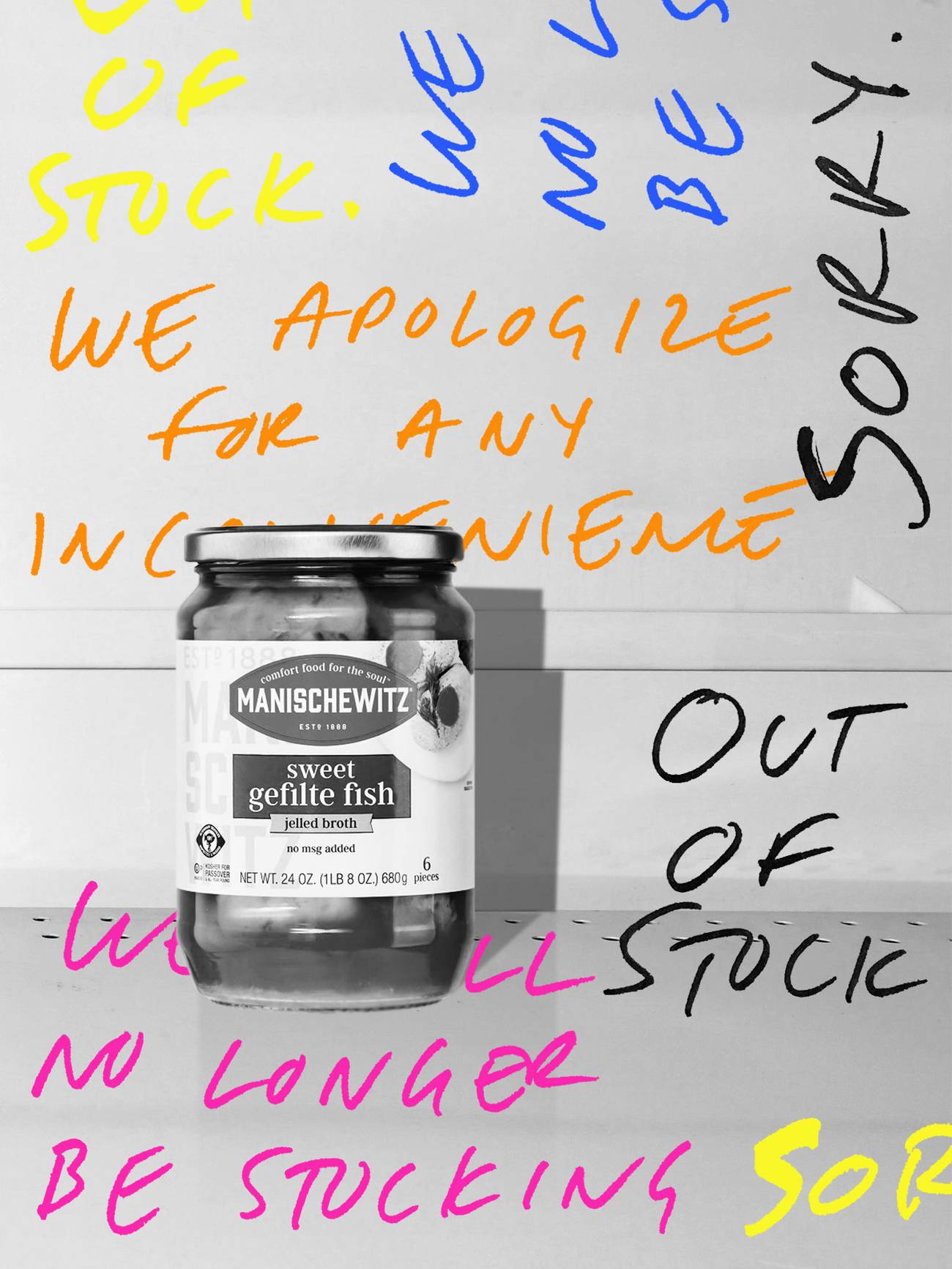

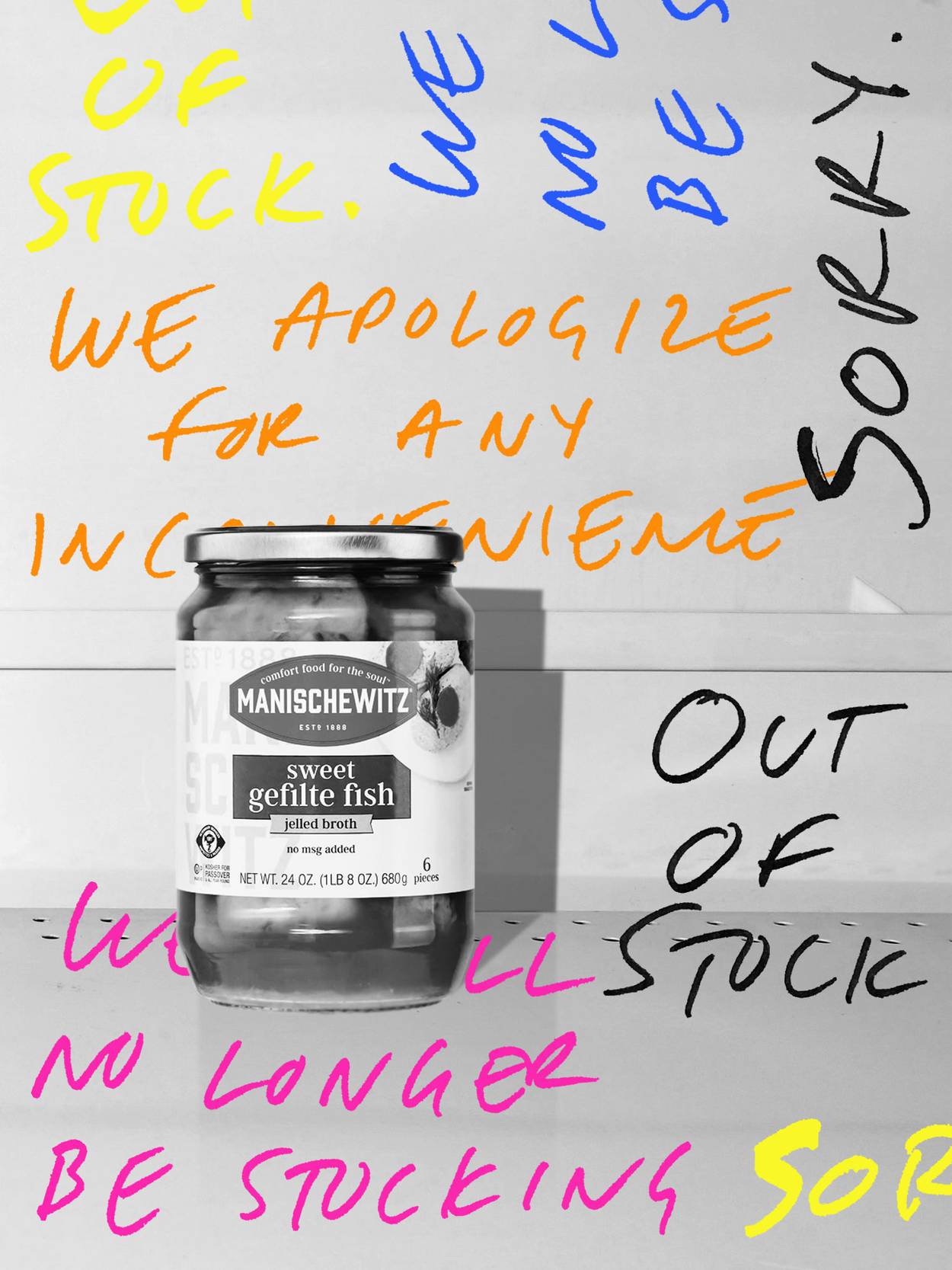

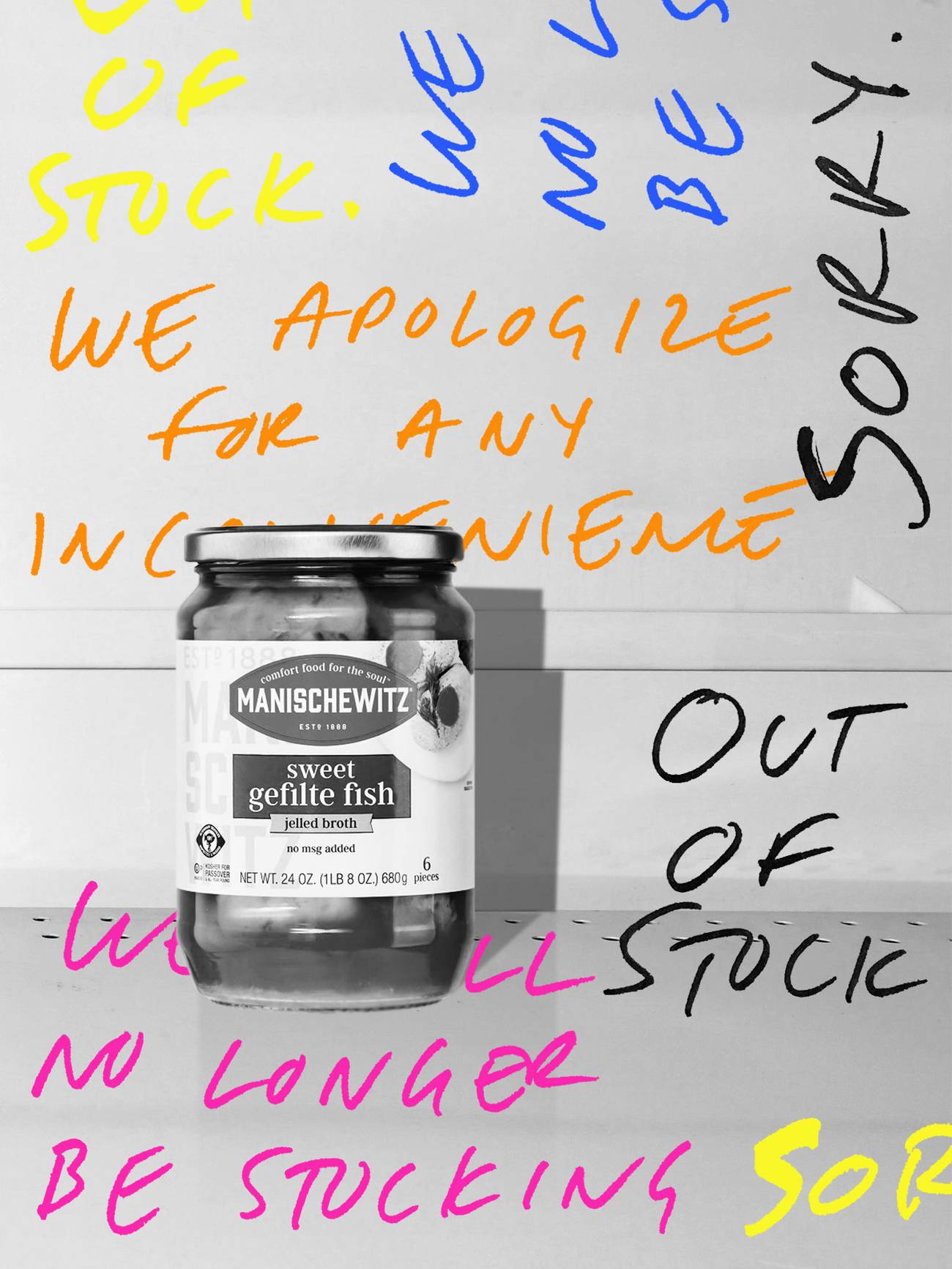

This all changed in October 2021 when Kroger dropped what appeared to be a bombshell on the community: the news that it’s reducing its kosher options.

The news spread like wildfire in Columbus’ tight knit Jewish community and inspired a backlash against Kroger. A number of Facebook posts, letters to the editors, and calls to rabbis went out, and with them, disinformation. One memorable letter to the editor juxtaposed the closing of Krogers’ kosher section with Kristallnacht, and from the general sentiment and reaction it wouldn’t be hard to think Kroger had fully done away with all kosher food at its Whitehall location.

This isn’t exactly the case. According to Amy McCormick, Columbus corporate affairs manager of Kroger, the independently owned bakery, the city’s only full-service kosher deli counter, and the accompanying prepared-food deli offerings—like kosher rotisserie chickens—will be discontinued in January 2022. The shelves of frozen food and prepackaged necessities, however, will still be there.

From Kroger’s perspective, removing a deli counter may seem like a routine business decision, but to the Jewish community it means much more. Rabbi Hillel Skolnik of Congregation Tifereth Israel in Columbus said that to him, “the loss of fresh meat and prepared food is a serious loss to the community, and the move makes Columbus significantly less desirable to religious Jews, which isn’t nothing.”

Shira Cohen, a Columbus resident who observes kashrut, sees her family relying more on kosher caravans visiting the city, rather than visiting a brick-and-mortar store. Her family has used the caravans before—companies that drive in kosher meat from other cities, generally once every month or two. These are a good short-term solution, but the meat typically is priced higher than locally sourced meat, due to delivery costs, and is also usually sold in bulk sizes. As a stopgap measure it works, but long-term for many Columbus families the caravans aren’t fully viable.

Plenty of smaller cities with less robust Jewish communities—in the Midwest, notably Des Moines and Omaha—not only have kosher delis but are even able to maintain kosher restaurants. Why not Columbus?

For years the Jewish community trailed in size to the two other big Ohio cities. Cleveland with a burgeoning Jewish center, and Cincinnati with a sizable community of its own, made Columbus something of an afterthought in the Ohio Jewish community.

With Columbus’ growth, this has turned around. The city’s Jewish population grew by 19% to around 25,000 in the last 10 years, according to a 2019 survey, trailing Cincinnati by just 7,000 Jewish residents. But Cincinnati has kosher restaurants. And in Cleveland, on top of kosher butchers and restaurants, a fully kosher supermarket called The Grove recently opened. It’s a pretty stark difference for major cities in the same state.

Columbus is one of the fastest growing cities in America, which helps explain the growing Jewish population. But for Jews, having kosher shopping options matters when people are deciding where to live.

For Skolnik, the kosher section at Kroger was a value proposition for his family when they decided several years ago to move to Columbus from Orlando, Florida. His family toured Columbus and evaluated the different kosher options before his move and were satisfied that what they found would lead to a good quality of life. But without the Kroger kosher section, that proposition could be about to change for the community.

Kroger’s changes can be seen as sort of a vote of no confidence in the continued growth of Columbus’ Jewish community, even if the issue for the supermarket chain might simply come down to limited store space. If a growing city, with a growing Jewish community, wants to keep expanding, kosher food options are essential.

Jewish Columbus, a partnership organization between the Columbus Jewish Federation and Columbus Jewish Foundation, is leading the charge in searching for sustainable alternatives. They recently launched a survey to Columbus’ Jewish community on kosher-keeping, they’re hosting community listening sessions, and they were also involved in a recent kosher restaurant popup kitchen.

A restaurant in Bexley, Cafe Istanbul, spent three days during Hanukkah with a kosher meat kitchen under the supervision of Buckeye Kosher, a Columbus kosher-supervision agency. Jewish Columbus CEO Joel Marcovitch said that the popup had over 450 reservations for its three-day run. (He also raved about the steak kebabs.)

In some ways, local kosher businesses may actually have been held back by Kroger’s kosher offerings; a small market or butcher couldn’t compete with the supermarket chain on selection or price. So Kroger’s decision might spur new businesses to open.

“I’d like to thank Kroger for their support for kosher food and products in the community,” said Marcovitch. “Supermarket space is incredibly important and they need profits to maintain and it’s a competitive industry. The fact they had it for so long, we’re incredibly thankful. Coming together and problem-solving and thinking this [through] together is what Jewish Columbus is all about.”

Marcovitch and Skolnik echoed the sentiment that this opens a gap in the community that they hope a community member can step up to fill. But to have truly sustainable kosher options in the community, it takes a large amount of buy-in not previously seen. That could be the difference between Columbus becoming a destination for the young Jewish professionals Jewish communities are fighting to bring in, or languishing and making do with even smaller kosher sections at local supermarkets.

Max Littman is a writer and graduate student at Johns Hopkins University currently living in Baltimore.