At least Ruth didn’t have to fret about social media.

The only thing this Moabite woman, arguably the world’s first convert to Judaism—and ancestor of one King David—had to do was hold on to her mother-in-law and promise to go whither the older woman went. She wasn’t expected to share photos of her challah rising on Instagram, defend Israel on Twitter, bare her soul on Substack, or cultivate small communities of followers on Facebook. Her journey was decidedly private, intimate, all but forgotten if it weren’t for the Bible’s author peeking in and recording the grandeur of her experience for posterity.

Today, we have a new class of Ruths, only this time many of them are trying to negotiate some of the most profound and pressing questions facing Jews—about identity and belonging, about money and politics, about making friends and losing faith—along with public or semipublic profiles. They are new Jews, but—if we are lucky—they will be among the most important Jews in the coming years.

To illustrate the role we believe Jews-by-choice are increasingly playing in the American Jewish future, we matched each of our interviewees—Nissim Black, Leah McSweeney, Steven Philp, Tommy Collison, and Nellie Bowles—with an iconic image from the recent American past.

Because every religious evolution is a conversion—every day brings with it the possibility of changing in ways until now unexpected—the stories these men and women tell us are particularly meaningful, and their wisdom so keenly appreciated. There are, to be sure, many more who share their trajectory, but here, in their own words, are some thoughts from these visible and inspiring people making their journey back home to Judaism.

nissim_blackNissim Black

Rapper

Nissim Black is no stranger to change, having moved from a career in gangsta rap in Seattle to a becoming a devout Christian before finding Judaism and emerging as one of its most popular and inspired musical ambassadors. Here he is embodying one of our other bards—Bob Dylan, seen here in a limo as chaos swirled around him outside London’s Royal Albert Hall. A bit more than a week earlier, Dylan had famously gone electric, provoking a betrayed fan to yell “Judas!” But the troubadour wasn’t moved much. Change, he realized, was the only constant for someone chasing that thin, wild, mercury sound that has guided truth-tellers from the biblical prophets onward.

I was born in Seattle. I was exposed to a lot of violence and drug use and abuse. By the time I was 9, I was already smoking weed, and by 12 I was already dealing with and running with the wrong crowd. Interestingly enough, my grandfather came to live with us at this time, and that was my first exposure to religion. He was a Sunni Muslim, I think he had converted in prison where he had spent most of his life, and then shortly after that he went on, back to prison for a probation violation. Because of that, from that point on, that was the only real encounter I had, really had from religion. So I would say that I was a Muslim. I had friends that knew I was very interested in hip-hop, and by the time I was 13 I recorded my first record with a local producer named Vitamin D. And that was big for me because it gave me the opportunity to take it from just being a hobby to realizing that this was going to be my future. From then on, I never stopped.

When I found my way to Judaism, a few years before I converted, I made what I thought was going to be my retirement album, which was a really positive deviation from the album that I was making prior. It was only natural and fitting because at that point I had changed my life so obviously the music was going to take a different direction also.

That album set me up in a way. The first single had a lot of spins on MTV. The video did very well. I headlined a couple of festivals, and played South by Southwest. Everything was starting to happen. And I left everything. I just couldn’t make the two worlds work. For me it just didn’t seem like it was going to fit, both of those worlds together. So I left the music, and I thought that was going to be the end of it.

It wasn’t till years later that people started encouraging me: Listen, you have a gift, you should use it now to bring people closer to Hashem, to spread your light, to spread emunah in the world. And I was like, yeah, no thank you.

But then my son started getting sick with meningitis, my baby that was 4 months old at the time, and I went and I prayed and I cried and I started to wonder and ask, what am doing that I shouldn’t be doing and what am I not doing that I should. I started to think about the music and, by this point my wife was also in surgery, and I was shutting everybody down. So I prayed and I gave God an ultimatum. I tested him. I had this broken microphone in my closet in my basement, and I said to God: If you want me to do this, if you want me to make music again, and this is really coming from you, then you got to make this microphone work. If it doesn’t work, I’m going to take it as a sign that this is all nonsense or whatever. Lo and behold, after I was done praying my microphone ended up working. I recorded a whole album on that microphone. I should probably hook it up now to see if it works. You know, crazy story. So I went to ask a rabbi, specifically the rabbi I was closest with who I thought would tell me I couldn’t make music any more. I really wanted another test. And after a two-hour lecture, he gave me the green light, and eventually music came back into the picture. —Nissim Black

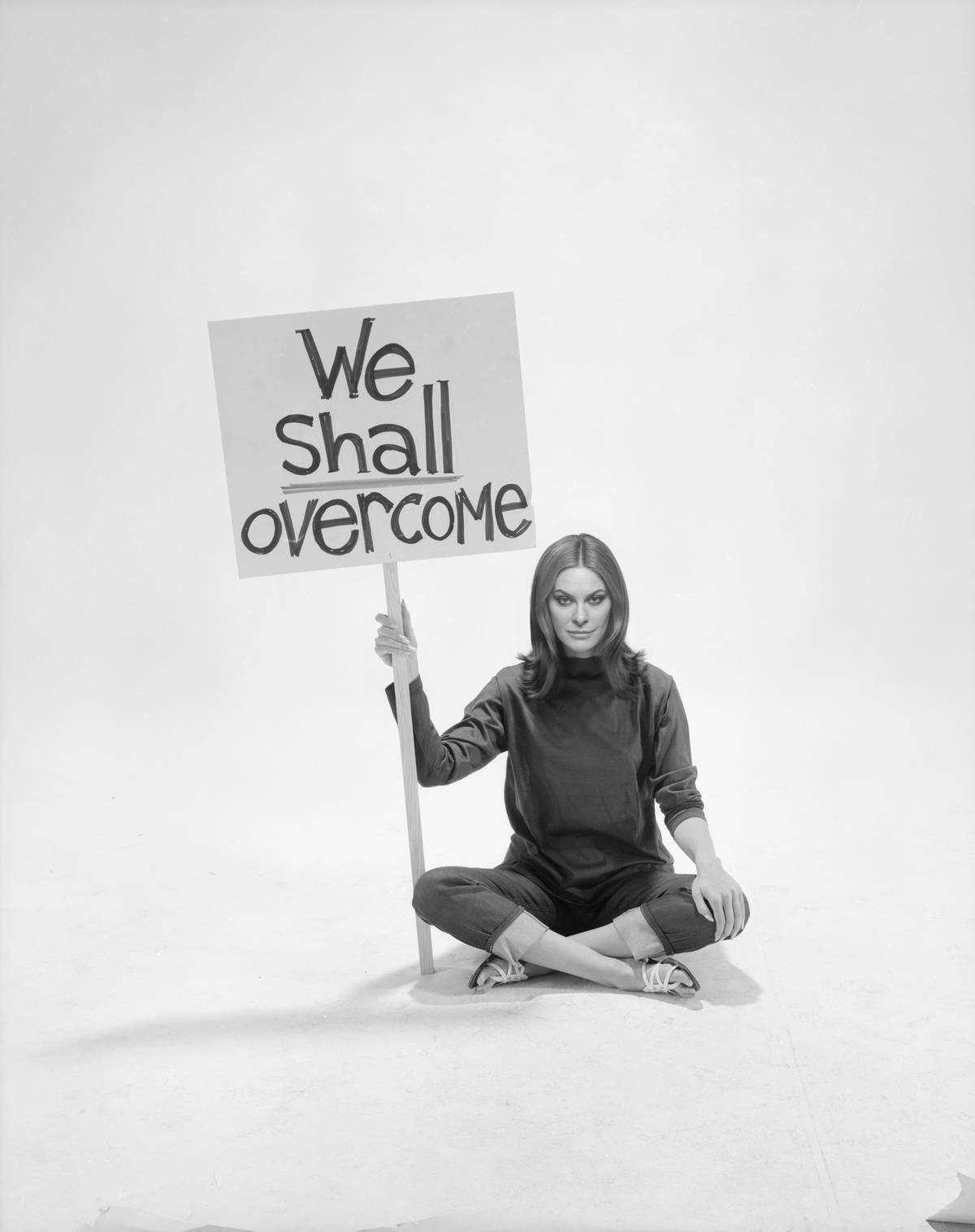

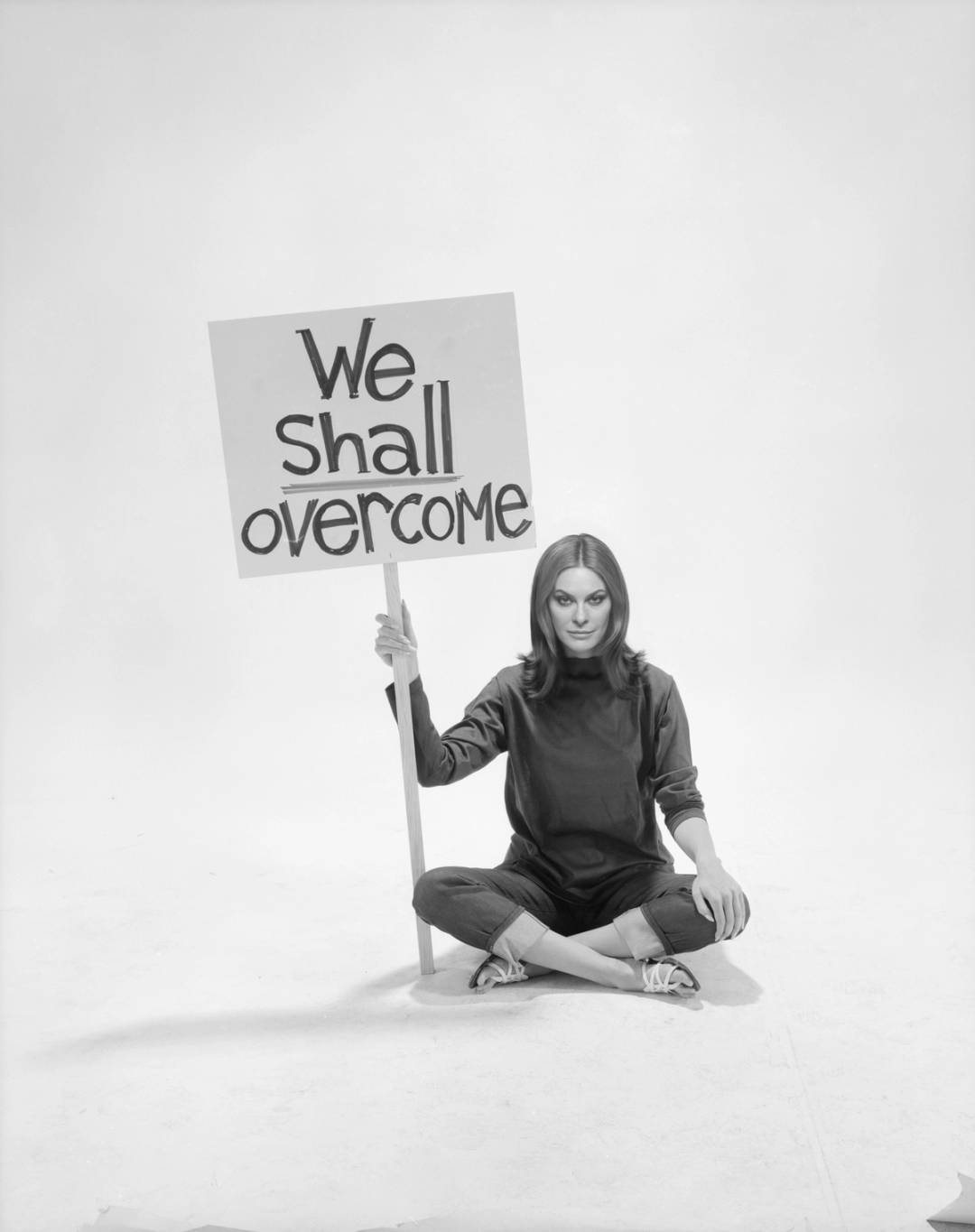

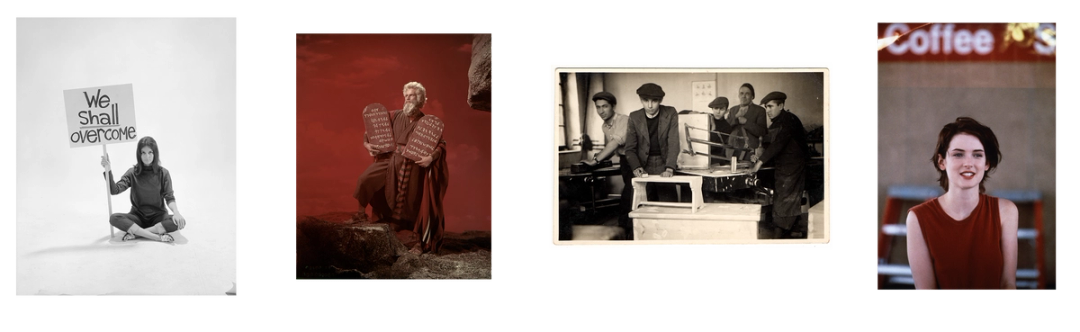

leah_mcsweeneyLeah McSweeney

Fashion Designer and Reality TV Star

Leah McSweeney is a fashion designer, small-business owner, and cast member on The Real Housewives of New York. But she made some of her highest profile waves with her reporting and writing on women’s issues—including as the co-byline on this magazine’s 2018 exposé of the Women’s March. She’s here matched with legendary feminist icon Gloria Steinem. Just as Steinem had done throughout her long, varied, and very public career, McSweeney, too, is another Jewish girl engaging with the feminism of her moment—even as what that means keeps shifting and changing.

What is it like to go through a conversion process in public? It’s so nerve-wracking. You know, Dave Chapelle likes to say that he never talks about being Muslim in public, because he thinks his religion is so beautiful he doesn’t want to be a stain on it because of whatever he does. Filming The Real Housewives of New York and talking about it made me feel so anxious. I didn’t want to look exploitative. And I was worried, because I have such an immense respect for all religion but obviously especially for Judaism. And I wanted to get words of encouragement and welcome, but I was also very worried about being judged.

I also had all these feelings of guilt. Early on in my conversion process, I went to the Park East kosher grocery store, for example, and had a moment of thinking I’m going to be the worst Jew ever, because I couldn’t ever truly keep fully kosher the way you’re supposed to. The store’s owner asked me what was wrong, and I told him how I was feeling. He said to me, it says in the Torah to just try your best. And so I felt very much like I didn’t have to worry about not doing everything perfectly, because, really, no one can. And this insight made me feel warm inside. It made me feel so confident. —Leah McSweeney

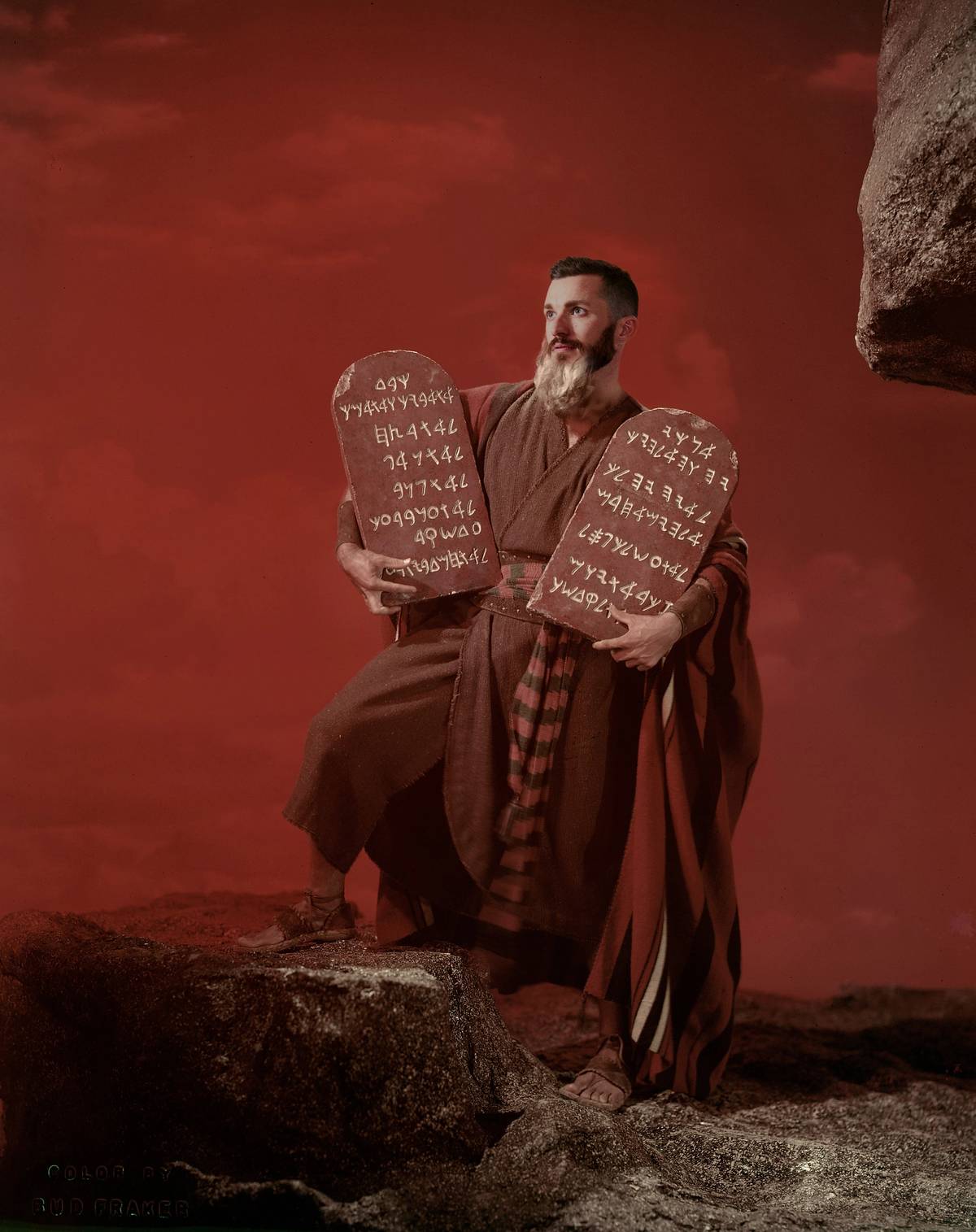

steven_philpSteven Philp

Rabbi

Like that old TV ad—“I’m not just a client, I’m president of the company”—Steven Philp isn’t just a new member of the flock; he’s now also a rabbi leading the rest of us. As a Hawaii-raised boy who found Judaism in Los Angeles and immediately gravitated to its fierce insistence on welcoming in the stranger, Philp—now a rabbinic fellow at Park Avenue Synagogue in New York—takes great comfort in shepherding others. When asked if he’d like to pose as Moses in the iconic Hollywood recreation of that moment on Mount Sinai, Philp was giddy. “I’m particularly delighted by the idea of subverting the image of Moses as a queer convert,” he said, laughing. “Perhaps this could be a tikkun on Charlton Heston’s unfortunate politics.”

An important part of my rabbinate is modeling the different ways you can look and be Jewish. And part of the reason that I’m insistent on being an out convert as a rabbi—some people keep it private, that’s their individual prerogative and its fine—is that there are so many misconceptions in our community about what it means to be or to look or to act or to move throughout the world as a Jew. People don’t understand that the challenges of being part of the community for those who have chosen to join it don’t end at the mikvah. There are a lot of well-meaning people who ask you at the Kiddush line why you chose to convert, which is a deeply personal journey, and a lot of information to potentially share with a stranger, even a well-meaning one as you try to load things on your plate.

So I have to constantly remind myself what it felt like to walk into the Westside JCC in Los Angeles for my first ever Shabbat service, being afraid, nervous, not understanding what was happening, and how grateful I was when the person at the door handed me a siddur, and when they saw I was confused asked if I needed a transliteration guide. Or how grateful I was to the person who when I went to services for the first time by myself, invited me to sit next to them. Or to Rabbi Sharon Brous, who stood up at that first service, and said that whether it’s your first or hundredth time, whether you were born into Judaism or not, you are welcome in this sacred space. To remember the alienation, the sense of grappling with what I didn’t know, and also remembering the people who helped me feel welcome, remembering that it’s hard to walk into these spaces, that for adults it’s hard to do something as a beginner, to meet that person and tell them that they’re welcome and let’s learn together—that’s what my rabbinate is about. —Steven Philp

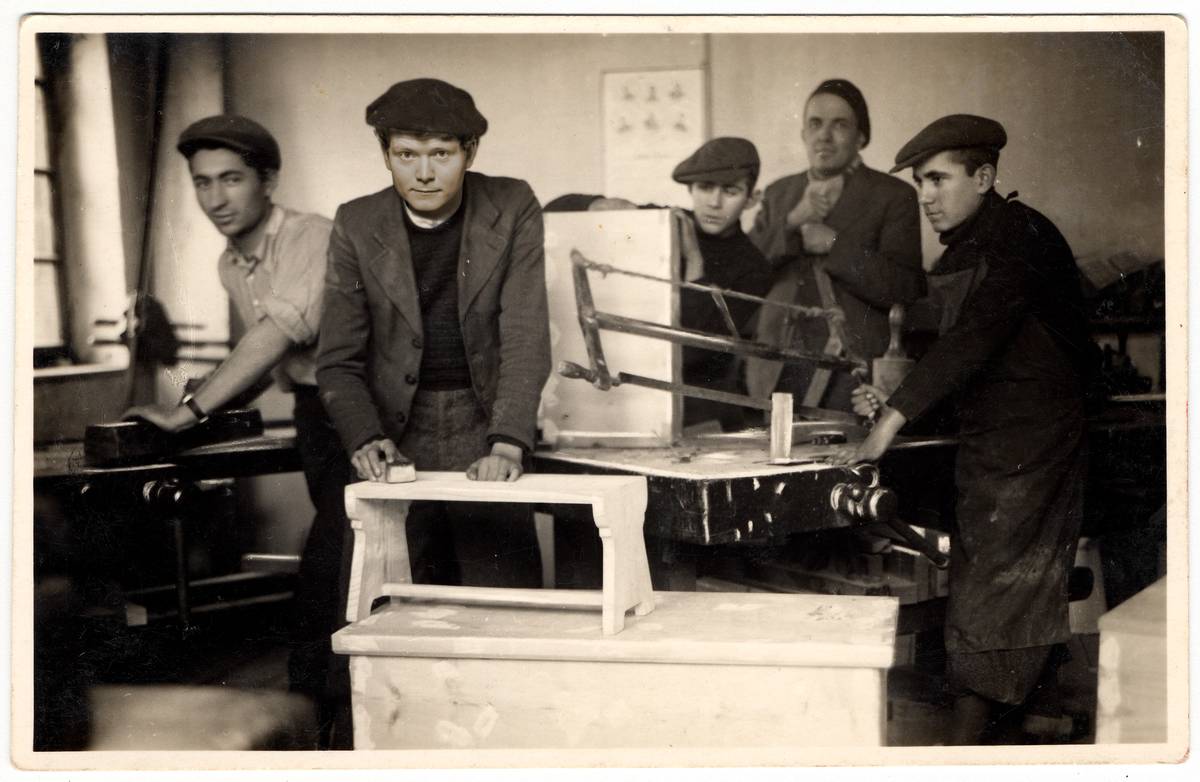

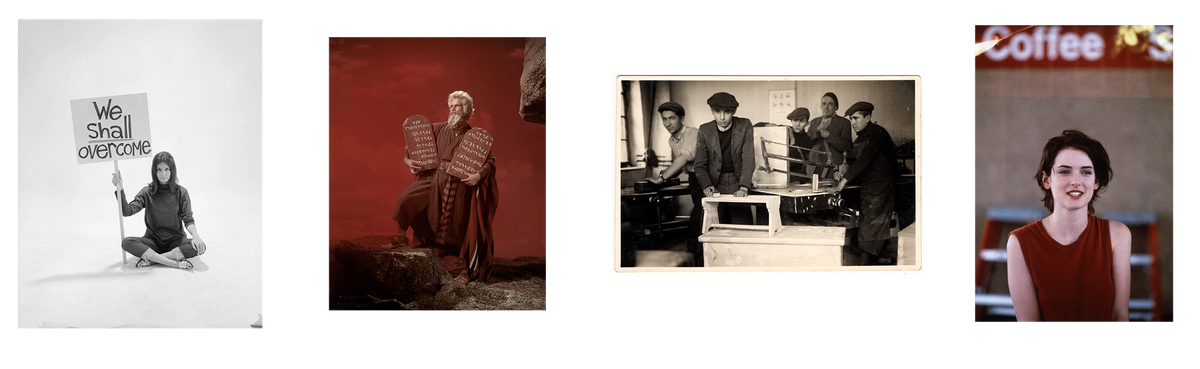

tommy_collisonTommy Collison

Writer and Entrepreneur

Tommy Collison is a tech executive—as well as a voracious reader who keeps a blog of every book he’s ever read. Still, he nonetheless knows that even the most astute students have got to make a living if they want to get serious about the life of the mind, and his current job is as head of communications strategy and business development for Lambda, an online coding school that allows its members to pay their full tuition only after they get a job. It’s the sort of communal-minded arrangement that would have seemed right at home in the alte-heym, including in this town in present-day Slovakia, where young religious men can be seen in the carpentry shop at a combination yeshiva and vocational training school (hachsharah).

If there’s a convert who wakes up the morning of their Beit Din appointment and feels totally sure of their decision, I’d love to meet them. If there’s a convert who has that sort of skies-open-up epiphany moment, I’d like to meet them, too.

Whenever somebody asks me my conversion story, I feel somewhat pressured to have a grand, overarching narrative. It started here, I’d say, and then, in a sort of well-executed-Agatha-Christie-plot sort of way, we’d get to the final part of the story where the strands all come together in a satisfying resolution. But if this is actually anyone’s story of adopting a new religion, I’ll eat my chumash.

In truth, my own story has its own unique fits and starts. I live in the Bay Area, which must be up there as one of the most interesting places to be religious in the world. In a city that looks askance at religion yet empties out at the end of August for Burning Man, it’s less of a question of whether you believe in something and more a case of discovering just what people adhere to. Antonio is a person you want to talk to about this phenomenon. This hasn’t happened to me, but it’s not hard to imagine the reaction if you introduced yourself to some new friends or coworkers and mentioned that you meditate for 10 minutes. You’d get approving nods, maybe someone expressing jealousy about how you have the time or the ability to focus. I can’t imagine the same reaction if you mentioned that you start each day by praying for 10 minutes.

Converting to an established ancient religion is seen as strange precisely because it’s in vogue to mix and match and create unique, individual religions. Maybe you grew up going to Mass on Christmas and Easter but you now follow Buddhist ideas. Maybe you have no religion but identify with the ethos and the community of Burning Man. Converting to an age-old religion is seen as strange precisely because, if you’re intellectually honest about it, you have to import it wholesale, not just the parts that work best for you.

As I experienced more of Judaism, I began to realize that it was operating on two levels simultaneously. First and foremost, it seeks to elevate ordinary moments and to have separate times and separate actions: Without candles and a willingness to stop working, it’s just a Friday night; without the blessing, you’re just washing your hands. But more than that, it tries to provide a playbook both for life’s challenging moments and its most quotidian. Beyond engaging with God or with the Torah, being Jewish is intimately concerned with how I interact with food, time, money, and other people. To the extent that being Jewish is demanding of me, it feels demanding of my actions, not necessarily my faith in God. —Tommy Collison

nellie_bowlesNellie Bowles

Journalist

In a sense, Nellie Bowles is a contemporary Liz Taylor, another convert whose commitment and clarity prodded Jews themselves to consider the gifts this tradition must include to have enticed such a radiant person our way. But there is something deeper about Bowles’ inquiry into her own faith journey, something that is both fiercely intellectual and tenderly intimate, which comes across in her popular Substack, and which remains both resolute and vulnerable and somehow consistently inspiring. Here she is partnered with another writer—Lelaina Pierce, the Reality Bites character played by none other than Winona Laura Horowitz. Like her, Bowles also reads to us as a generational dream girl, traversing the cleavages of her social and political moment, and somehow remaining impossible to ignore.

Some people talk about converts as sort of like a trans-ness experience, like you were always a Jew and you discover your Judaism. I don’t know if I necessarily align with that philosophy. I don’t know if I was always a Jew inside and just discovered my Jewishness. I think the first moment that I was like, this is going to be my life, was probably when I was reading Heschel and learning about Shabbat. Because digital detox has so well permeated the urban working anxiety ambitious female lifestyle already, I kind of clicked into that. Like, OK, digital detox is just like Shabbat, so let’s get really into Shabbat and see how that goes.

And reading Heschel and then trying to understand how Judaism elevates time, and how time can be made into a sacred space, into a holy space, it just worked for me. It just held my mind and brought me a lot immediately. And the deeper I go, the more it brings me. I want to not drive on Shabbat. We already do no phones and all of that, no computers and no TVs.

But there hasn’t just been one moment that made me feel suddenly Jewish. Instead, I found another metaphor that was useful for me, the idea of naturalization. It comes from a congregation called Romemu in New York, and what Rabbi David Ingber says, that becoming Jewish is like becoming a citizen of another country. It’s about walking into a culture, a history, all this stuff. With Christianity, it’s a belief: If you accept Jesus into your heart, you are saved and that’s it, poof, done, you’re in. Judaism is just not that way. It’s slow, more of joining a culture. So when someone comes to France, how long till they start feeling more French than American? It’s hard to put words to it. —Nellie Bowles

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.