In the early 2000s, Abe Schwarz was working and living in Echuca, a small town 115 miles north of Melbourne, Australia, where he was tasked with organizing a conference to discuss the prevention of youth suicide in the area. After this conference, an Aboriginal elder from the Yorta Yorta clan approached Schwarz to ask if he was “from the Hebrew mob.” When Schwarz confirmed that he was Jewish, the elder told him that he had “always wanted to meet someone of the mob that my mob tried to save.”

The elder then described the details of an incident that was well known among members of the Yorta Yorta Aboriginal clan, but mostly unknown to members of the Australian Jewish community.

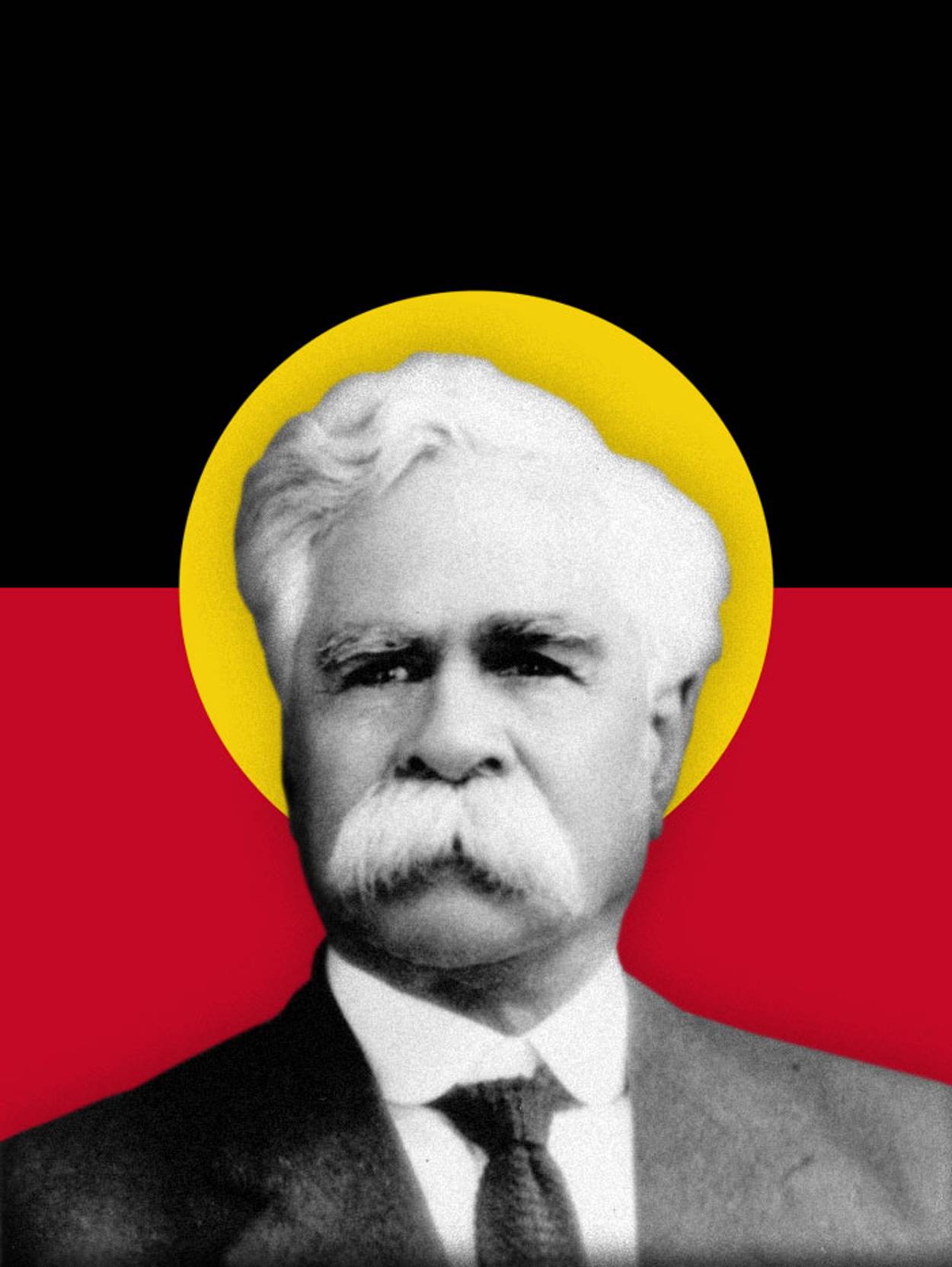

On Dec. 6, 1938—one month after Kristallnacht—a 77-year-old Yorta Yorta Aboriginal man named William Cooper had led a delegation, along with members of the Australian Aborigines League, to the German Consulate in Melbourne to deliver a letter protesting the violence against Jewish people in Germany. The letter was refused, and Cooper and his delegation were turned away from the consulate.

This protest on behalf of European Jews was extraordinary—not just because Cooper was protesting an injustice that many countries had failed to properly address, but because Cooper himself was an oppressed Australian Aboriginal man trying to fight for his own rights, yet nonetheless felt compelled to take the time to call out the injustice against European Jews thousands of miles away.

Schwarz was intrigued. As he told Tablet recently: “The next day I called the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne and asked them for more information.”

“It took the centre some time to pull together the facts,” he said, “but they were able to verify the story through newspaper clippings in their archives which had been published on Dec. 7, 1938, the day after Cooper’s delegation was turned away from the consulate, and some prior research undertaken by members of the Jewish and Aboriginal communities.”

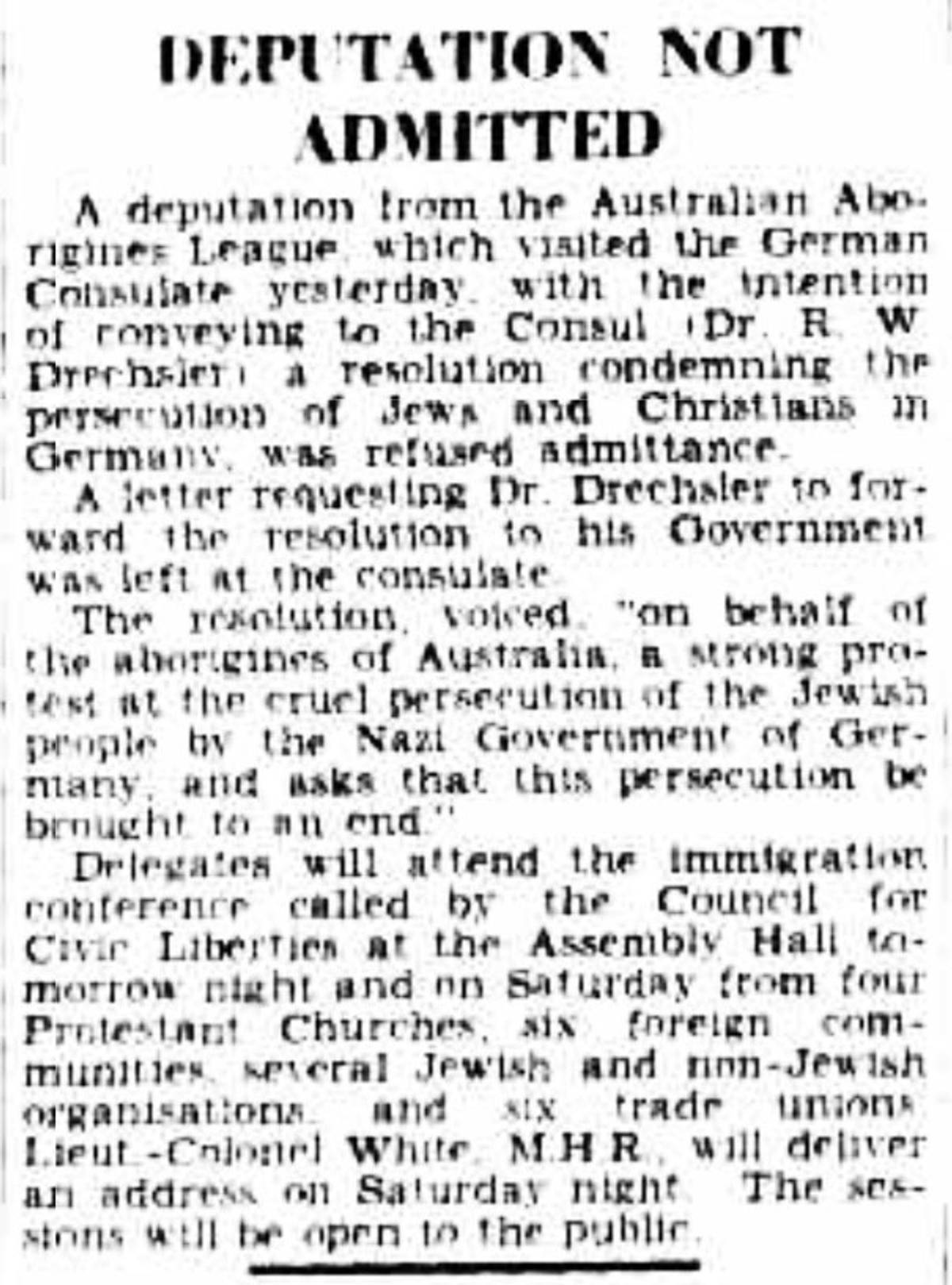

The newspaper clipping from the Melbourne newspaper The Argus noted that “a deputation from the Australian Aborigines League, which visited the German Consulate [in Melbourne] yesterday, with the intention of conveying to the Consul a resolution condemning the persecution of Jews and Christians in Germany was refused admittance.”

‘The Argus,’ Dec. 7, 1938National Library of Australia

Cooper’s 92-year-old grandson, Uncle Alfred “Boydie” Turner, told Tablet that the story was particularly remarkable because “as far as I know, Grandfather had never met a Jewish person in all the years of life. But he was always a person that if he thought he could bring peace between people or something was going wrong, he was the one who would stand up for people and call out harassment. He had been doing that since he was a kid.”

For Schwarz, this chance meeting in Echuca profoundly changed his life: He founded the William Cooper’s Legacy Project, which dedicates itself to telling the story. He also became close friends with Uncle Boydie, Cooper’s grandson. They speak regularly on the phone and they have been on three joint missions to Israel, including in 2010 when former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, who was then Australia’s foreign minister, unveiled an academic chair in Cooper’s name at Yad Vashem.

And just a few weeks ago, on Dec. 6, 2020, the German government formally apologized to members of the Australian Jewish and Aboriginal communities for refusing to accept Cooper’s original protest letter, exactly 82 years earlier.

At this poignant event, held online due to COVID-19 restrictions, Felix Klein, the German government’s commissioner for Jewish Life in Germany and the Fight against Anti-Semitism, read a formal apology: “Officially on behalf of the Government of Chancellor Angela Merkel, we are sorry that the 1938 Consul-General in Melbourne would not accept the letter of the Aborigines League, nor forward it on to the political leadership here in Berlin, as would have been the right and morally correct thing for a Consular Official to do,” said Klein. “The solidarity shown at the other end of the world with people in greatest trouble is a role model and impressive until today. Unfortunately, there were very few examples like this.”

Klein also thanked Cooper “for reminding us that, so long as doing the right moral thing remains our guiding values, even those without any basic human rights of their own can be upstanding for others and call out injustice and persecution, wherever in the world others might be suffering.”

For Turner, this apology was heartening and the culmination of a lifetime of work to have his grandfather recognized for his important work protesting injustice. “I’m am over the moon to hear this apology, it just blew me away,” he said, “I think that Grandfather would have been incredibly pleased.”

This apology gives testimony to the fact that during WWII, the Aboriginal people of Australia were keenly aware of the terrible events oppressing Jews in Germany and they were ready to speak up and condemn the persecution of Jews, in a strong show of commitment to justice, unity, and solidarity among the people of the world.

Yorta Yorta Aboriginal woman Lois Peeler also found the apology meaningful: “The apology from the German government affirms the view of the Australian Aborigines League under the leadership of William Cooper—staunch human rights advocates—that human rights should be accorded to all peoples,” she said. “The work of this organization had long focused on the Australian government’s lack of action to address the civil and human rights of Aboriginal Australians and so readily recognized the treatment of Jews as a violation of human rights—it did what it did best in organizing a campaign to draw public attention to the plight of the Jews by walking from the Melbourne suburb of Footscray to the German Consul in Melbourne to deliver a formal written protest.”

For Jayne Josem, the museum director of the Melbourne Jewish Holocaust Centre, the formal apology was symbolic. “It is important for leaders and governments to make these sorts of statements and to take ownership of past mistakes and injustices,” said Josem. “The German consul acted inappropriately by not accepting the petition, and William Cooper is a great example of an Australian that stood up and protested, especially at a time when Aboriginal persons had no rights in Australia.”

When this story gained prominence over the last 20 years, the Holocaust Centre in Melbourne acted decisively to institute a small but permanent museum display to tell the story of Cooper and his courage.

At present, the Melbourne Jewish Holocaust Centre is undergoing extensive renovations, but when it reopens, Josem notes, there will be a new section that displays the Australian responses to Kristallnacht, with plans to have an even more prominent display of Cooper’s story.

“Many Holocaust survivors were blown away to hear about Aboriginal Australians protesting on their behalf at a time when Jewish people were being stripped of their rights in Europe,” said Josem, “and we want to continue to teach visitors and students that they can make a difference using the inspiration of the story of Cooper and his courage.”

For many Holocaust survivors, this apology provides an important form of closure for one of the most infamous incidents relating to the Holocaust in Australia and provides them with comfort that this injustice has now been formally rectified.

A Melbourne resident of the past 70 years, 95-year-old David Prince—a survivor of the Lodz Ghetto, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and the Friedland labor camp—thinks the apology was important, but also questioned the 82-year delay. “I think it is a good thing,” said Prince, “however, I do wonder why it took so long. The German government should have made this apology long ago. I think it has less of an impact so many decades late, but better late than never.”

For Schwarz, a historic injustice has finally been righted. “The apology has helped to finish the business that William Cooper set out to do,” said Schwarz. “Even over 80 years later, I still take comfort from the fact that a group that had no rights of their own were the ones to stand up for Jewish people when we were being slaughtered on the other side of the world and every time I think about it, I am still absolutely touched.”