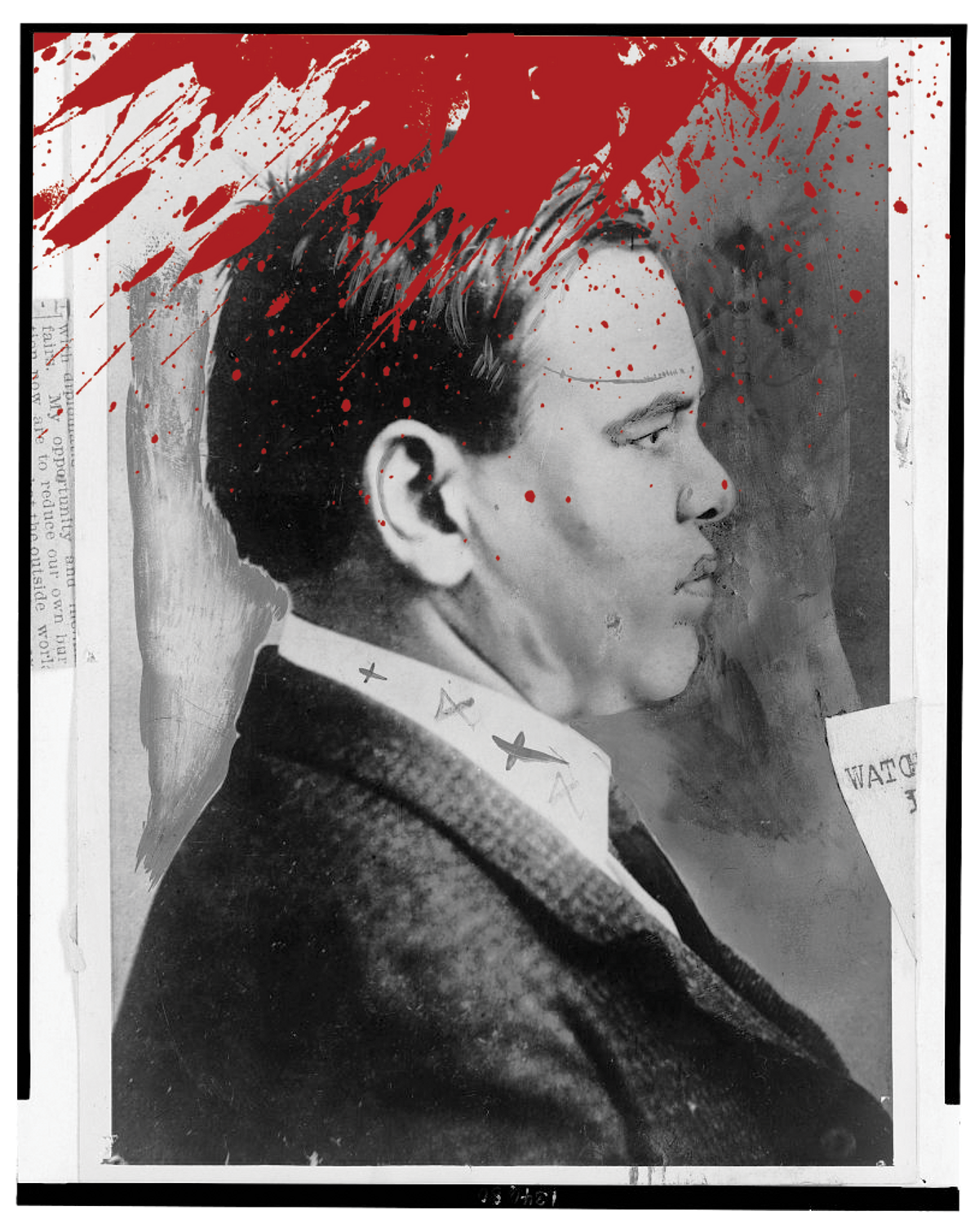

The Hectic, Violent, and Relatively Short Life of Big Jack Zelig

The Lower East Side gangster would shake down shopkeepers before saving elderly Jews from harassment

“Imagine if a greenhorn fresh from Ellis Island came upon this impressive funeral. He would have surely assumed that it was for a man of great distinction in Israel, perhaps a luminary in the Torah, and if not a respected figure in the community then at least a great philanthropist. So it would be in the old home. How astonished the greenhorn would be to hear that the parade to the cemetery was for a leader of robbers, murderers, and cadets whose greatest virtue was his iniquity.”

—Forverts (Forward), Oct. 8, 1912

The proverb, derived from the Gospel of Matthew, that those who “live by the sword, die by the sword” was all too true in the hectic, frequently violent, and relatively brief life of Big Jack Zelig. For about four years, from 1908 until he was murdered on a trolley car by a shot in the head from an aggrieved underling on Oct. 5, 1912, at the age of 24, Big Jack was one of the reigning Jewish gangsters of the Lower East Side. He was a man to be feared. As The New York Times aptly put it the day after he was killed, “he had plenty of that kind of courage which is possessed by a man with a revolver and a gang at his heels when dealing with some unarmed opponent and his readiness to use a revolver or knife soon won him a measure of respect in gang circles.”

Yet despite his various swindles and shakedowns of Jewish shopkeepers and business owners, he still garnered respect among the East Side’s Jews, mainly for protecting elderly and more vulnerable members of the community from assaults and antisemitic harassment. Even Abe Shoenfeld, who was the young chief investigator for the New York Kehilla’s Bureau of Social Morals and certainly no fan of the neighborhood’s Jewish criminal element, begrudgingly admired Zelig. “At all times he has had the reputation … as being a good scrapper and above all a man of principle which readily understood is a quality seldom found amongst thieves. You may find honor but never principle,” Shoenfeld wrote in August 1912. He also described the gang leader as having “prevented more hold-ups than a thousand policemen.”

Decades later, Judge Jonah Goldstein, who grew up on the East Side and was starting his career as a lawyer when Zelig ruled the area, remembered that Big Jack would literally “beat the stuffings” out of any hoodlum he witnessed bothering a Jew riding a trolley car. Zelig and his gang members “made it possible for the Jews not to get tossed around,” said Goldstein.

Thus, Zelig was a bit of an enigma: a ruthless, though stylish, rogue with a soft spot for his fellow Jews—the same people whose pockets he picked, the ones he sold tickets to social events that did not take place, threatened if they did not hand over the “protection” money he demanded, and beat up if they dared do something to displease him. Zelig did not play favorites when it came to making money: He took advantage of the increasing number of labor disputes in New York by offering his “expertise” to garment factory owners and union organizers alike.

He was born as Zelig (or Selig) Zvi Lefkowitz on May 13, 1888, in an East Side tenement, one of nine children of Ephraim (Frank) and Sarah Lefkowtiz, two among the thousands of Jewish immigrants from Russia who several years earlier fled the persecution and poverty of the Pale of Settlement for New York City. (The couple first settled in London in 1882 with their infant son Hyman and later relocated to Glasgow. After their arrival in England, Sarah gave birth to another son, Alex. Ephraim journeyed to New York City in 1884 and Sarah and the children eventually joined him.) In New York, Frank made a decent living as a tailor, but young Zelig was restless and by the age of 14 he had joined the small army of teenage pickpockets under the tutelage of one of the East Side’s many “Fagins,” Simon “Crazy Butch” Erenstoft.

Butch taught his young charges an assortment of tricks, including the “snatch racket,” in which he would drive a bicycle into someone walking on the street, which in turn would trigger a commotion. Inevitably a crowd gathered to watch the altercation and, in the confusion, pockets were professionally picked of wallets and other valuables. Life, however, was tenuous as an East Side thief and—as Herbert Asbury relates the story in his classic 1927 book, The Gangs of New York—Butch died in a fight at a pool hall when he was about 22 years old.

Butch answered to one of the first true Jewish gangster bosses of the East Side, Edward (Osterman) Eastman from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, otherwise known as Monk Eastman (his father had changed the family’s surname). He looked exactly as you might expect for a nasty and brutish thug: “a bullet-shaped head,” “cauliflower ears,” and a nose bent out of shape from being frequently broken. Adept at using brass knuckles and blackjacks, Eastman “loved violence for its own sake,” writes historian Albert Fried. He was a favorite among Tammany officials for “keeping” voters in line at election time and also worked both sides of labor disputes “strong-arming” for employers as well as strikers.

The Eastman gang, of which Jack Zelig was a member, had a bitter and deadly feud with the Italian-led Five Points gang that erupted in a wild shootout on Second Avenue in August 1903. About six months later, Eastman, while attempting to rob a young man who had a Pinkerton detective as a bodyguard, shot and killed the detective in a fight. For this crime, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. (Later, after he was released and imprisoned again for burglary, Eastman served in the U.S. Army and saw military action in France during America’s one-year involvement in WWI. For this service, the state’s governor granted him back his citizenship rights. But in 1920, after becoming a bootlegger during the beginning of Prohibition, he was murdered by a federal enforcement officer whom he had a dispute with.)

After Eastman went to prison, his gang was led for a few years by one of his lieutenants, Max Zweifach (or Zwerbach), a 20-year-old Austrian Jewish immigrant who was known as “Kid Twist.” To gain control of the gang, Zwerbach, who was as treacherous as his mentor, had his chief rival, Richie Fitzpatrick, a former Five Points gang member, murdered. He expanded the gang’s protection racket, ensuring that madams and gambling and stuss operators paid what was expected of them and on time (stuss was a version of the card game faro that was popular among Jewish immigrants in New York of this era) and was equally determined to keep the East Side free from Italian and Irish thugs. His rivalry with the Five Points gang ultimately cost him his life in May 1908 when he and one of his men were shot to death at Coney Island by “Louis the Lump” Pioggi. The story was that Kid Twist and Louis the Lump loved the same woman: Carroll Terry, a Canadian-born music hall singer.

With the demise of Monk Eastman and Kid Twist, Big Jack Zelig, who had done stints in reformatories and prisons, was next in succession—though there were challengers—to head the Eastman gang. He had a tough and frequently mean crew watching his back that included “Whitey” Lewis (Jacob Seidenshner), Louis “Lefty Louis” Rosenberg, and Harry “Gyp the Blood” Horowitz (Gyp the Blood was infamous for his “skill” at breaking a man’s spine with ease over his knee). Zelig was smart and brought some efficiency, if you could call it that, to his “business.” Among the services he offered were: a knife slash on the cheek for up to $10; a bullet in the leg or arm for up to $25; throwing a bomb for up to $50; and murder for up to $100. He never lacked for clients willing to pay him and his boys. More importantly, he protected his territory against encroachment by other mainly Italian gangs.

There were dangerous enemies around every corner. Zelig carried on the rivalry with the Five Points gang but was “on mildly friendly terms” (as Zelig’s biographer Rose Keefe puts it) with Jack Sirocco and Bowery saloonkeeper Frank “Chick” Tricker. Neither was to be trusted, however. Sirocco’s ultimate goal was to replace Zelig as head of the Eastman gang. In late 1908, Zelig added to the bad feelings with the two men, when acting on the orders of Abe Lewis, an Eastman gang leader, he threatened to kill Tricker. But at the last second, Zelig lost his nerve and escaped. He hid out in Chicago for a time. Accompanying him was his common-law wife Henrietta (Young) Zelig—who was eight years older than him—and her young son Harry; she claimed Zelig was the boy’s father. They lived in a rented apartment on Broome Street.

More disputes followed. Physical fights ensued and death threats were made. Finally, Sirocco and Tricker had enough and dispatched a gunman-for-hire Julius Morrello (Julie Morrell) to kill Zelig. One night in early December 1911, Morello showed up inebriated at a casino on Second Avenue planning to murder Zelig. “Where is that big Yid Zelig? I gotta cook that big Yid!” he was reported to have shouted. Zelig was ready for him. According to one version of this story, the lights in the hall went out, shots were fired, and Morello lay on the floor dead. While Zelig fled the scene, he was eventually apprehended, though no charges were brought against him since there were no witnesses to substantiate that Zelig had been the shooter. The killing of Morello, however, started a bloody gang war.

In June 1912, a brawl broke out between Zelig, Lefty Louis, Whitey Lewis, and Tricker and members of the Five Points gang. All of the participants were arrested. A short time later, when Zelig was released on bail and departed the courthouse, Charles Torit, an associate of Sirocco, approached him from behind and shot him in the head behind his ear. Somehow, Zelig survived and while he was recuperating in the hospital his men attacked Tricker and his gang causing much concern among New York City’s police and justice officials.

Once Zelig’s life was out of danger, he was transferred to the Tombs to await his bail hearing. While there, he later said he was approached (for a second time) by “Bald” Jack Rose (Rosenzweig)—also known as “Billiard Ball” Jack Rose (the nickname was because he was bald, hairless, and pale, rather than about his prowess playing pool), who acted as a money collector for New York City police Lieutenant Charles Becker. By most accounts, the NYPD officer was extorting brothel owners and illegal gambling operations and offering them protection from legal charges. One of the affected gamblers, Herman Rosenthal, objected to Becker’s constant money demands and publicly declared his intention to expose him. Rose asked Zelig—allegedly at Becker’s behest—to supply four gunmen who would assassinate Rosenthal. Zelig later claimed that he had refused to assist Rose, who he believed was acting on his own accord. In any event, on July 15, 1912, as he left the Metropole Hotel, Rosenthal was murdered by a team of four gunmen all associated with Zelig—Gyp the Blood, Lefty Louis, Whitey Lewis, and Dago Frank (Francesco Cirofici). All four were later convicted of the killing and executed, as was Becker, whose culpability in Rosenthal’s murder remains a matter of contention to this day.

Zelig’s connection, as tentative as it was, to the Rosenthal-Becker case—without question the greatest scandal of the pre-WWI era—and his scheduled testimony for Oct. 6, 1912, about Jack Rose’s request of him to assemble the gunmen, initially led the police and newspapers to believe that Zelig’s murder on the evening of Saturday, Oct. 5, were linked. It is not entirely clear. In one accepted version, it was unrelated events that led “Red” Phil Davidson, a petty thug, to wait for Zelig, follow him onto a trolley car and fire a bullet into the back of his head.

Davidson was a fruit seller, who was coerced to pay protection money. He became acquainted with some young minor gangsters, who robbed Jewish pushcart peddlers, snatched purses from women on the street, and held up stuss players. He also worked as a pimp and was reputed to be a “horse poisoner.” His ambition was to join Zelig’s gang. Though Big Jack humored him, he never thought Davidson was tough enough to work for him.

On Friday, Oct. 4, Davidson, who may have been slightly inebriated, approached Zelig at a social function, where Zelig and his friends were drinking and playing cards. Some words were exchanged about who was buying drinks and Davidson left feeling slighted. The next day, he approached Zelig again who was carousing at Segal’s Café at 76 Second Ave. More words were uttered and this time, Zelig became annoyed and punched Davidson, who left the café battered and bruised. He returned early in the evening and offered an apology to Zelig for the altercation. Zelig accepted and shook Davidson’s hand. But this was not the end of their dispute.

Around 8 p.m. that night, Zelig boarded a Second Avenue streetcar. Davidson, who had retrieved a gun, was waiting for him. As the streetcar slowed, Davidson hopped on its running board and moved sideways until he was close to where Zelig was sitting. Without saying a word, he took his gun out and shot Zelig in the head. He died a short time later. Davidson leaped off the running board and fled. He was soon arrested by a police officer who had been nearby the shooting. Davidson later claimed that Zelig had robbed and beaten him, yet as Keefe suggests, Davidson “muddled the investigation when he changed key details of his story.”

Zelig’s fellow gangsters were shocked by the killing and never believed that Davidson was “bold” enough, as The New York Times noted, to do the deed. The Times reporter also rightly pointed out that if Davidson had been hired by Rose or Becker to kill Zelig, he would have already had a gun with him when he first encountered Zelig that evening. Still, the timing of the murder less than 24 hours before Zelig was to testify in the Becker case remains highly suspicious all these years later. In any event, Davidson was found guilty of murder in the second degree and received a jail sentence of not less than 20 years in Sing Sing prison.

A crowd estimated to be about 10,000, young and old, who regarded Big Jack with a strange awe, gathered near his Broome Street apartment to pay their respects. A choir chanted hymns as the funeral procession passed. “Only the funeral of Rabbi Jacob Joseph [in 1902],” observed Abe Shoenfeld, “surpassed this, the funeral of Jack Zelig.” For his part, the esteemed editor of the Forverts, Abraham Cahan, had a difficult time understanding how someone of Zelig’s ilk, “the chief of a gang that for money cracked heads, broke bones and routinely committed murder,” was deserving of such deference. He never received a proper answer.

Historian and writer Allan Levine’s most recent book is Details Are Unprintable: Wayne Lonergan and the Sensational Café Society Murder.