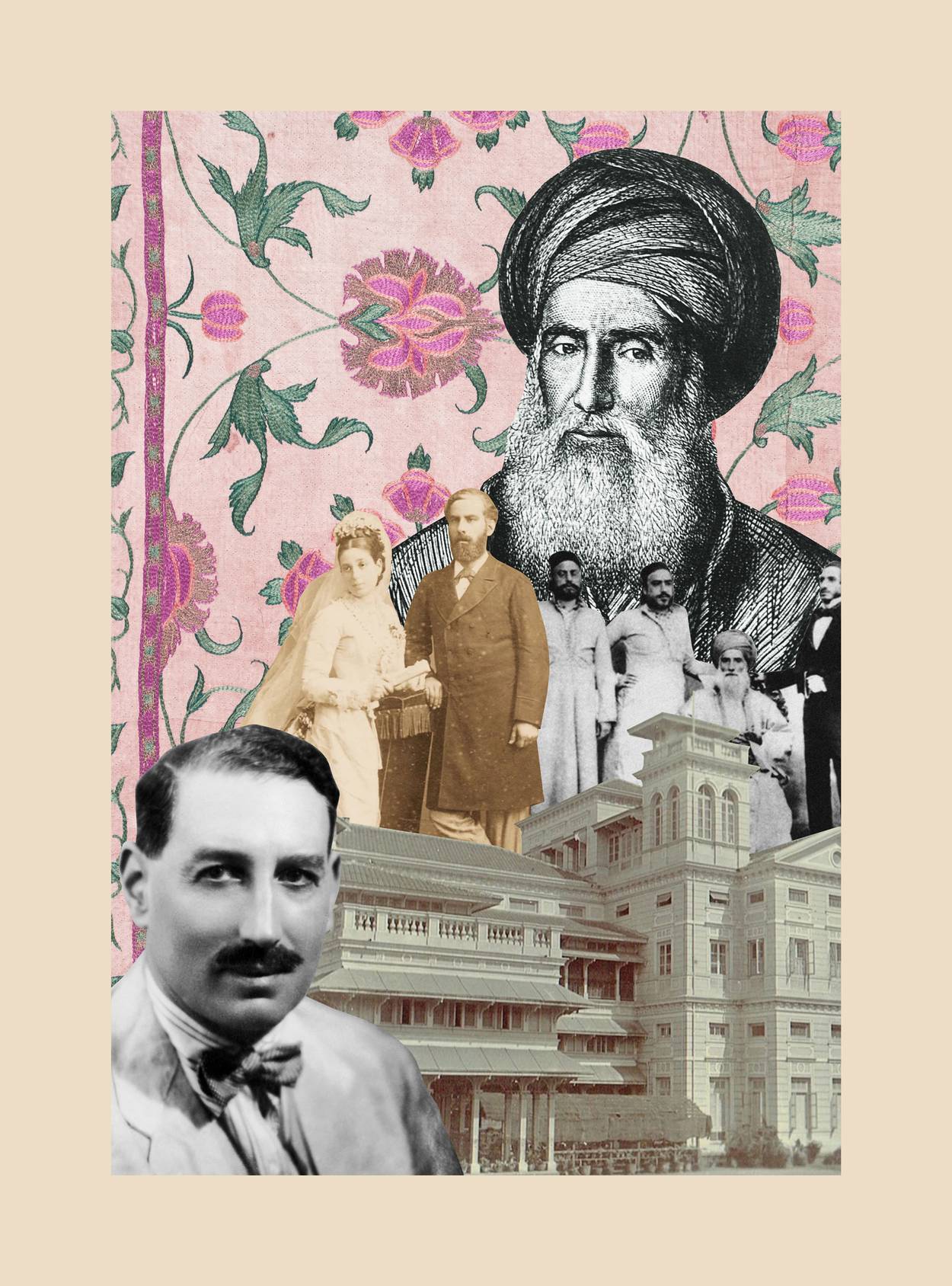

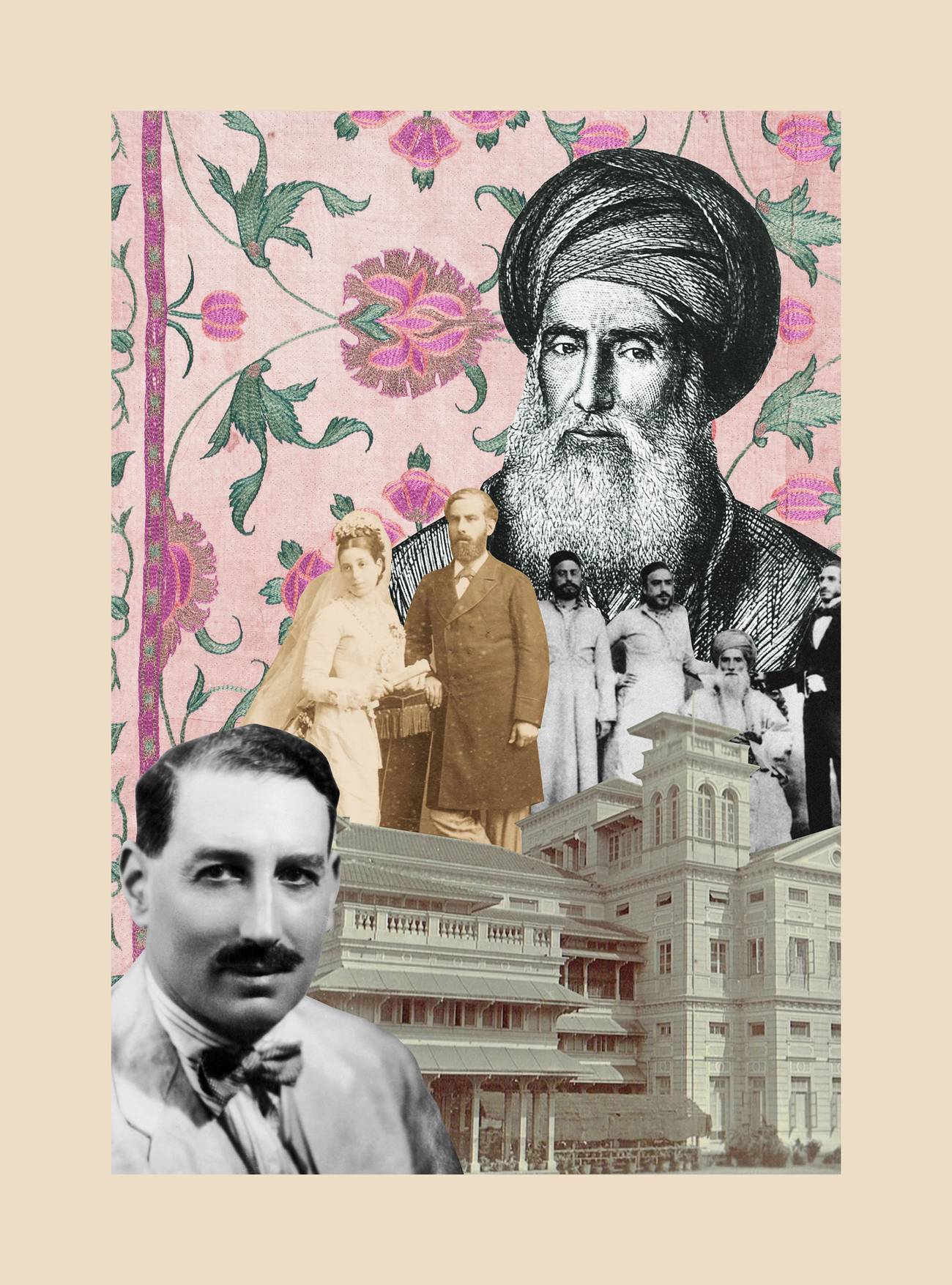

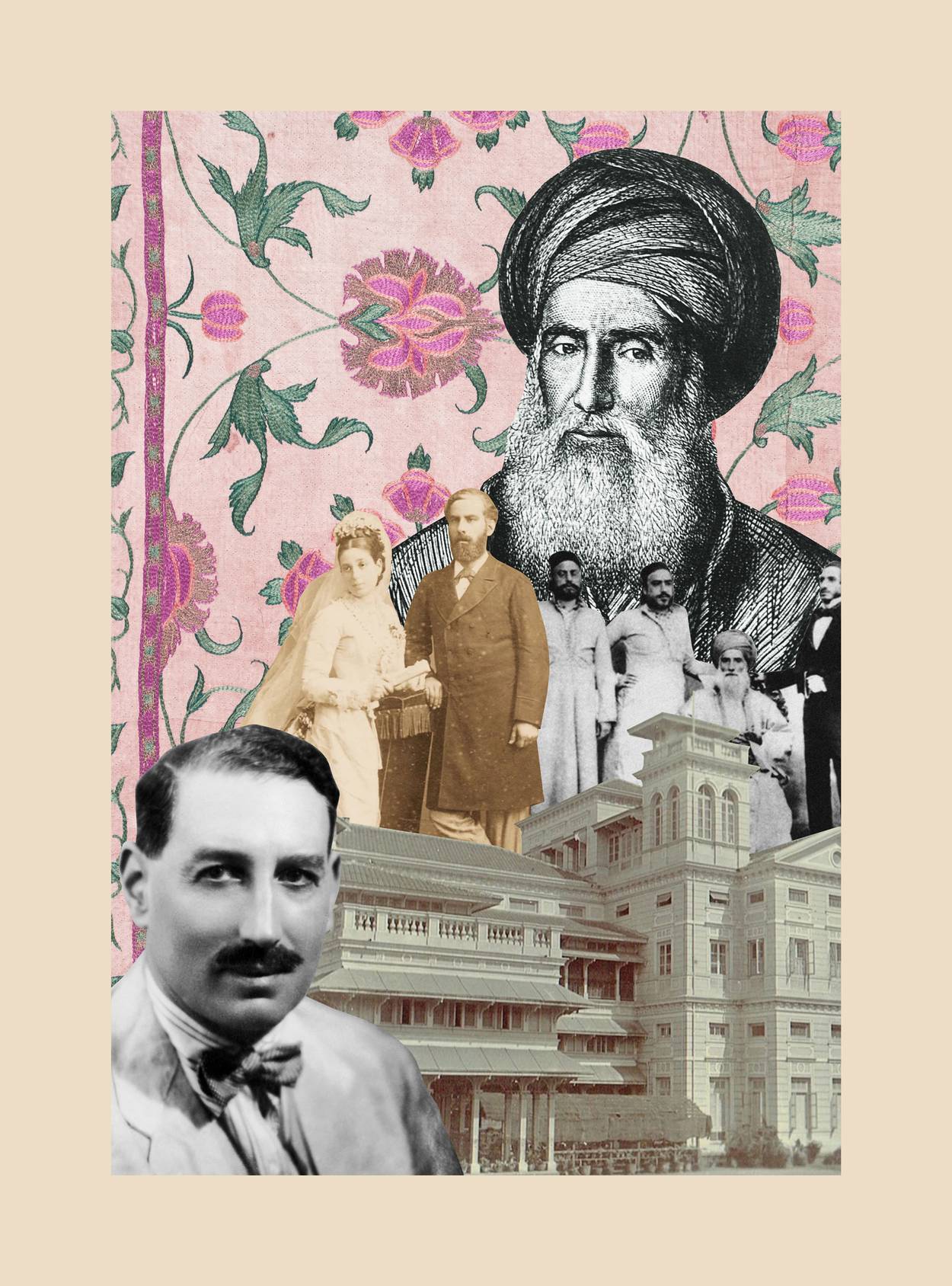

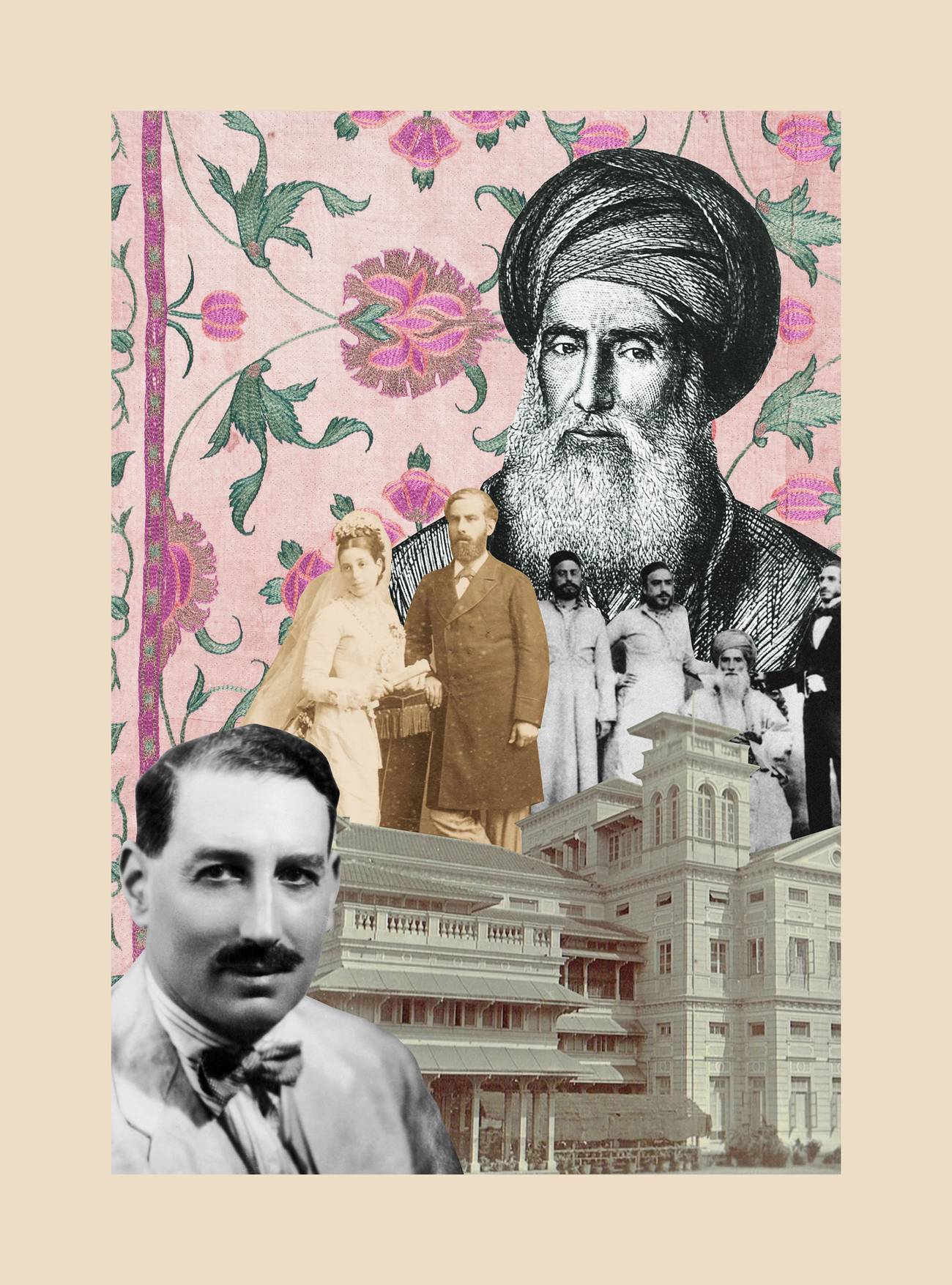

The Dramatic Decline of the ‘Rothschilds of the East’

The Sassoons were one of the most powerful Jewish families in Asia. What led to their fall from grace?

Across Asia, it’s not hard to stumble across traces of the Sassoons, the Baghdadi Jewish merchant family that came to be known as the “Rothschilds of the East.”

In Shanghai and Hong Kong, they built lavish synagogues, most still in use today. At Victor’s Cafe in Shanghai, named for Victor Sassoon and housed in his former hotel, visitors enjoy “Sassoon curry” with a view of the historic Bund district. In Mumbai, India—the former headquarters of David Sassoon & Co.—the name is difficult to miss: It’s on a historic boat dock, library, schools, and hospitals. And Jews who visit Mumbai can stay in the Sassoon House attached to the Magen David Synagogue—one of the largest synagogues in Asia outside Israel—for easy access to daily minyans and Shabbat services.

A century ago, the Sassoons were known worldwide; news of everything from their business activities to personal affairs made it into international media. For a time, they dominated up to 70% of the trade volume of Indian opium and also dabbled in cotton, silver, textiles, banking, insurance, and real estate. They were accepted as members of the British aristocracy at a time when Jews were only beginning to be accepted within society. Yet by the second half of the 20th century, there was no business to speak of; today, hardly anyone knows their name. How did one of the 19th century’s most successful dynasties rise and fall so dramatically while dynasties like the Kadoories and the Rothschilds persisted?

The story of the Sassoons is a classic example of the duality of assimilation and the refugee experience. Later generations of the family traded in their distinctive Baghdadi Jewishness for wealth and inclusion into British aristocratic life. In the end, this was one of the biggest mistakes that led to their eventual downfall, argues Joseph Sassoon, a descendent of the family, in his new book The Sassoons: The Great Global Merchants and the Making of an Empire. Sassoon, a professor of Arab studies at Georgetown University, digs into a treasure trove of untapped archives housed at the National Library in Jerusalem that had never before been accessed.

The book focuses on the David Sassoon family line—the one that escaped Baghdad in 1830 and established David Sassoon & Co. in Mumbai—while Joseph descends from one of David’s brothers. Joseph’s family remained in Baghdad until the 1970s when they fled Saddam Hussein’s regime. Growing up, Joseph would hear stories from his father about their famed relatives who made the Sassoon name famous.

But he took little interest in learning about his family until 2012, when he received a letter from another person named Joseph Sassoon, a distant relative living in Scotland, looking to connect with other family members. “I had no idea where these initial excursions would lead,” he writes in the book. But his interest was piqued, and what tipped the balance was the archive he discovered at the National Library in Jerusalem.

While most accounts of the Sassoon family—like The Last Kings of Shanghai, published in 2020—focus on the family’s activities in Shanghai, the tens of thousands of documents accessed by Joseph on the family business were used to chronicle its whole story, from the patriarch’s escape from Baghdad until the company faded from public life more than a century later. Most of those documents—letters, business correspondence and ledgers, even dinner menus—were written in Judeo-Arabic, part of the reason they had not been used before.

“Without that language, you really don’t have the ability to put together the story,” Joseph told me.

Fluent in Arabic, Hebrew, French, and English, and able to read Persian and Ottoman script, Joseph was able to uncover details and anecdotes never before reported about the family, one of which was particularly angering to write about.

That was the story of Farha Sassoon, who became David Sassoon & Co.’s first female partner and one of the first female presidents of a global company in 1894. Despite her “groundbreaking management of the business,” she was written out of other accounts of the family, or given far less attention than the men, including her husband. Farha was a driven and successful leader who reinvigorated the company in the decades following David’s death, which saw his descendants argue over company dealings and even branch off into a separate competitor company in Shanghai.

Unfortunately, Farha’s case was no exception. Her brothers, unable to accept her success, forced her out of the company after seven years of leadership. Relentless competition within the family ended up being another fatal flaw to the Sassoon company.

“I think that was really the biggest surprise,” said Joseph. “I remember sitting in the archives once and getting so angry at what they were doing, I mean, just absolute pure jealousy. They kept saying, how can a widow with three children run a global business? The fact that they were sitting in clubs in London and enjoying themselves and didn’t want to work never crossed their minds.”

By this time, the Sassoons had already turned their attention to joining the ranks of the British aristocracy, and as a result, away from the needs of the business itself.

This was a departure from the values on which David had founded the company, with Baghdadi Jewish identity as a core value. David had hired mainly within the Jewish community, closed business on Shabbat and Jewish holidays, and set aside a quarter of a percent of the company’s profits for tzedakah. He built synagogues and schools that taught both religious and secular education and raised his eight sons to be well-educated in Hebrew and Jewish texts as well as business. Business communications for years were written entirely in Judeo-Arabic to establish a sense of trust—it kept outsiders from reading the correspondence and cemented the company’s identity regardless of location.

David’s son and immediate successor, Abdullah, continued this tradition, but the generations following would slowly begin to see joining the British upper classes—rather than adapting the business to a changing world—as the answer to its struggles. Soon, they established a branch in London; Abdullah changed his name to the Anglicized Albert and was knighted in 1872.

Their sense of identity “was replaced by this desperate need to become part of the British aristocracy,” Joseph said. “And a part of being a member of this aristocracy is you do not work … and so that really became a major issue going forward.”

This was only one of many reasons the Sassoons failed. By the early 1920s, when Victor took the helm at the company’s Shanghai branch, the thing that made the House of Sassoon tick had been lost. Victor’s lifestyle was “a hectic blend of business and political commitments,” Joseph writes; he worked, but spent much of his time—and money—entertaining guests at his cosmopolitan hotels and night club in Shanghai, or traveling the world. When the Japanese invaded Shanghai in 1937, Victor made a vital misstep that helped sink the company by moving his wealth and business from India to Shanghai and assuming Japan would never attack.

Also, unlike the Kadoories, another Jewish merchant family that remains successful today, Victor missed the opportunity to invest in Hong Kong. When the Chinese Communist Party won the civil war in 1949, it seized the company’s assets, and by the 1970s, David Sassoon & Co. dissolved. Millions of dollars of the Sassoon fortune seemed to disappear when the business crumbled. An empire had fallen.

The communities they built and the infrastructure they left behind, though, are perhaps the most lasting piece of the Sassoon legacy in Asia. Solomon Sopher, president of the small remaining Baghdadi Jewish community in Mumbai, was made chairman of the Sir Jacob Sassoon Trust in 1998. When he assumed that position, there was “hardly any money left,” Sopher said. The community received assistance from the government to restore the Magen David Synagogue in 2019, but mainly relies on donations. It continues the tradition of tzedakah that David started nearly two centuries ago. “[We] look after the lesser fortunate individuals in the community, not only Jewish people; we also help non-Jewish people,” Sopher said.

At the same time, the Sassoons’ success represented a sort of paradox, the dark side of the assimilation story that allows a minority group like the Sassoons to rise in the ranks at the expense of the colonized by “following the sinews of the British empire,” said Paul French, an author and journalist who has written extensively about WWII-era China.

“The fact that they have to establish a branch in London, and that that branch eventually becomes the corrupting roots of the family—obsessed with the social calendar and all the rest—is inevitable, because the Sassoons don’t exist without the empire,” French told me. “And the empire doesn’t exist without the Sassoons.”

Jordyn Haime is a freelance journalist based in Taipei. She spent the past year researching Judaism in Taiwan under a Fulbright grant.