Fighting for Environmental Justice

In the American Southwest, Jewish activists are joining with Native American groups to fight climate change and destruction of sacred land

“Most of the things I’ve done in my life resemble the other things I’ve done in my life,” Charlotte Levinson explained. “But not so with the Stronghold.”

After 30 years at the helm of the Max and Anna Levinson Foundation, she plans to step down next year to turn the reins over to the next generation of leadership. But there’s one project for which she’ll continue to advocate beyond the end of her tenure: Apache Stronghold, led by Wendsler Nosie Sr. of the San Carlos Apaches in Arizona.

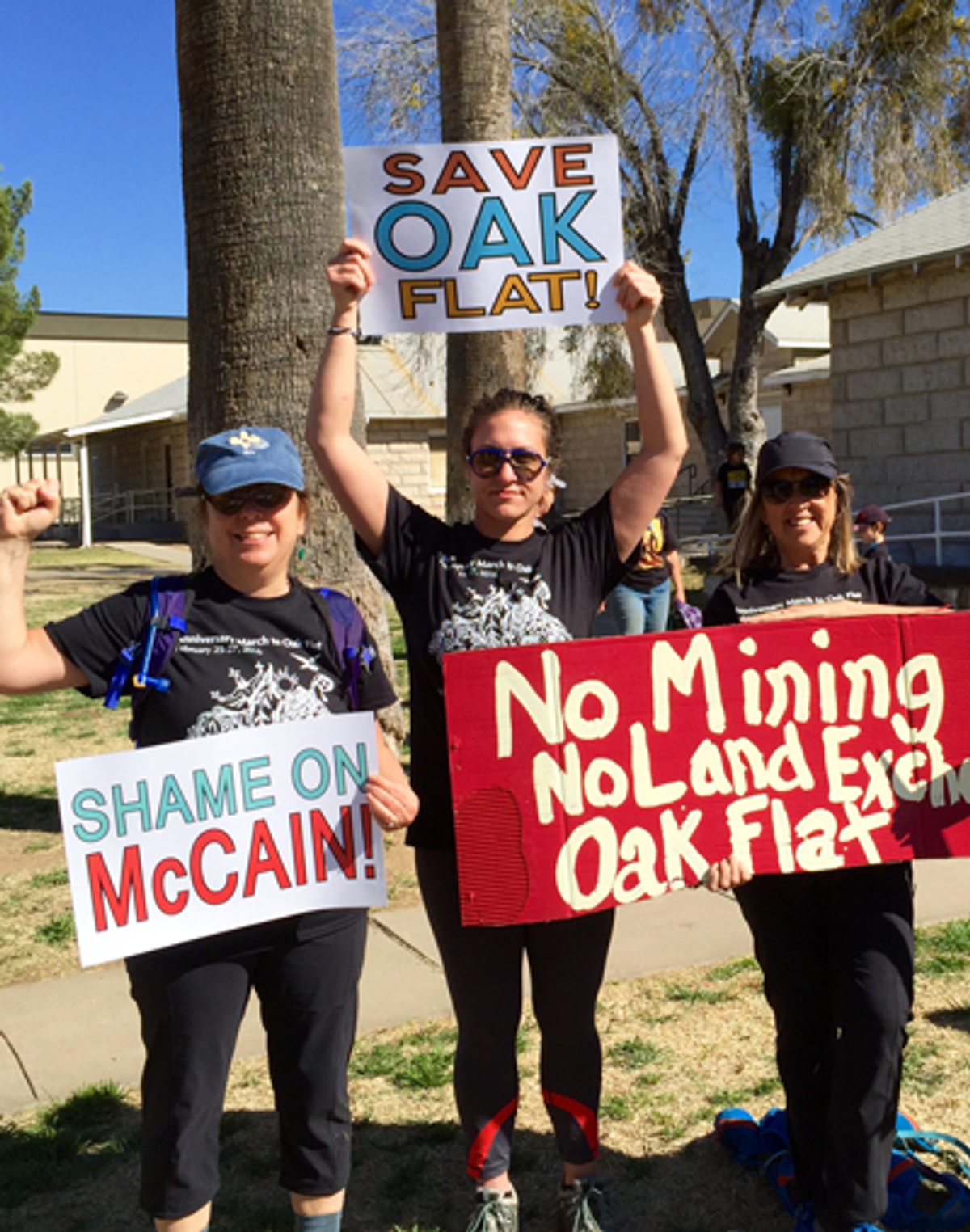

The Apache Stronghold, which is a community association promoting neighborhood programs and civic engagement, has been vigorously defending itself against existential threats on two fronts: at their sacred mountain—Mount Graham, or Dzil Nchaa Si An—where the Apaches’ access to the summit has been sometimes curtailed by federal road closures due to the construction of telescopes by the University of Arizona; and at a ceremonial site called Oak Flat where Resolution Copper plans to gouge out one of the world’s largest copper mines.

According to Reuters, the mine “would tunnel 7,000 feet underground, where rocks radiate heat from the earth’s molten core. It would suck up enough water to supply a city and leave a crater a mile and a half wide and 1,000 feet deep.” The contents of that crater would be piled on the surface nearby in a mountain of 1.6 million tons of waste, blighting the landscape in perpetuity.

The insensitivity to Apache concerns about the destruction of their sacred lands, medicinal plants, and cultural practices over many years has led the Stronghold, perhaps inevitably, to address the larger context of America’s founding with respect to First Peoples—mass extermination and theft of their homelands—and to work for a process of truth and reconciliation.

And that’s something that spoke to Levinson as president of the Max and Anna Levinson Foundation—named for her paternal grandparents, who fled the Holocaust. The philanthropic organization focuses on climate change, strengthening democracy and the free press, bolstering Jewish communal life in the Diaspora, and peace, social, and environmental issues in Israel.

“Germany has many monuments to the Holocaust, but we still haven’t gotten there with respect to the Native genocide,” Levinson said. “Their erasure is still not understood, faced, or in any way confronted in our educational system.”

Since meeting the members of the Stronghold after returning from the 2014 People’s Climate March in New York City, she’s been to Apache lands on five different occasions—walking, praying, camping, drumming, singing, breaking bread—“connecting in reciprocity and mutuality,” and not just human to human.

“I appreciate the Apache way of being in relationship with sister rock, brother canyon, mother earth—reclaiming the natural world in a spiritual and sacred way, that then informs the politics and strategies,” she explained.

At Stronghold events people often form a circle and say a few words.

“I am a Jew,” Levinson said at the Stronghold’s 2016 annual gathering at Dzil Nchaa Si An. “My grandparents were from Eastern Europe. In Europe we were not considered white. Like the indigenous people of the Americas, we were persecuted and killed, and suffered a genocide. My grandparents escaped. They came to New York, and assimilated. They thought that was the best thing to do. But I reject that, and I want to work with others to end all forms of racism, white supremacy, and domination of the natural world.”

Levinson recently hosted members of the Stronghold who were crossing the country in a caravan traveling to the mass rally on June 23 at the U.S. Capitol sponsored by the Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival. Apache Stronghold is an endorsing partner of the campaign, which is uniting poor people across racial, ethnic, and religious divides into a “new and unsettling force” to advance a moral agenda to eradicate systemic poverty. Similarly, Nosie has been working to unite Indian tribes, many of whom are facing their own extreme energy extraction battles. They stopped in Santa Fe, where Levinson and others prayed with them at the historic plaza, the site of a mass execution of 70 pueblo leaders in 1693 by the Spanish colonizers.

Steve Pavey, a documentary photographer, applied anthropologist, and activist who’s been documenting their journey as part of his ongoing Hope in Focus project, wrote in a caption on Instagram:

Overnight hospitality in Santa Fe, NM, from Charlotte connects us as family. This is also what “activism” can look like—becoming family, sharing prayers and becoming more human together, more of who Creator has meant us to be.

*

Levinson is not the only Jewish activist involved in Native American communities organizing around these issues. Two other Jewish climate change warriors in Santa Fe, both of whose work is supported in part by the Levinson foundation, also prioritize supporting Native-led environmental justice projects. And like Levinson, they’ve gotten involved by drawing on their Jewish heritage.

Through its Sol Not Coal program, New Energy Economy, a New Mexico nonprofit devoted to building a carbon-free energy future, has been sharing positive energy with indigenous peoples of northern New Mexico.

Literally.

This spring NEE solarized a community center at the Cochiti pueblo that will reap an annual cost savings of $10,000 for the village of 500. It is the latest of 10 such projects at facilities throughout northern New Mexico, four of which serve specifically Native communities.

According to Mariel Nanasi, NEE’s executive director, there are two threads in NEE’s activist DNA: the thread that’s actively challenging, opposing, and resisting centralized, polluting energy that’s put in the backyards of people of color, and the thread that’s exposing the vision of what’s possible.

“Leaders at Cochiti had heard that we’d solarized Tewa Women United’s headquarters in Tesuque and approached us about a project for their community,” she said. “This is exactly what we’d hoped to spur.”

Nanasi, who as a girl in Englewood, New Jersey, studied at yeshiva, takes to heart a passage from the Beyt Tikkun Hagaddah her family reads on Passover when pointing to the maror:

One of the most radical messages of the Torah is that cruelty is not destiny. Though we tend to treat others the way we ourselves were treated, the message of Torah is that the chain of pain can be broken.

At the event celebrating the installation of the solar panels, Nanasi saw faces “go from wary and skeptical to genuinely smiling.” Especially at the cost savings to the community center, which is in almost constant use as a basketball court for high schoolers, a health-care center for seniors, and meeting space for cultural events for community members of all ages.

“When they realized they would never have to pay another electrical bill, it was a treasure to behold,” Nanasi said.

Cochiti is now looking at solarizing other projects with funding partners that its members met during the collaboration with NEE, and that’s just fine with Nanasi.

Along with spreading the benefits of solar to communities who have traditionally been left out, NEE hopes to help create a demand for energy democracy. In Nanasi’s vision of breaking the chain of pain, nuclear and coal will not simply be traded for solar in a system that tends to skew toward shareholders at the expense of ratepayers.

“Energy is particularly important as a driver of our economy and our wealth. We’re at a moment in time where the energy companies could fall from their towers of greed and exploitation, but the people have to demand that because it’s not going to happen if we don’t,” she cautioned.

*

Rebecca Sobel, climate and energy senior campaigner for WildEarth Guardians, counts Levinson and Nanasi among her most trusted allies in the Keep It in the Ground movement—especially in the campaign to spare the thousand-year-old ruins of Chaco Canyon and the mostly Navajo residents living nearby from the adverse health, cultural, and environmental hazards of extreme oil and gas extraction.

It’s almost too great a number to take in, but 91 percent of the land in New Mexico in the greater Chaco area that’s available to be leased to oil and gas for fracking wells has been leased. The Chaco Culture National Historical Park is in this area, as are hundreds of people whose homes and health are affected by the fracking frenzy in Eastern Navajo.

“Being in Chaco is a profound experience,” said Sobel. “It has a similar feel to being in Jerusalem at the Kotel—a point of power and gathering. For Natives, that feeling comes from standing at the walls of the great houses at Chaco.”

The best that New Mexico Sens. Udall and Heinrich have been able to offer as a legislative protection is a 10-mile buffer around the park, which puts Sobel in the absurd position of having to oppose the Chaco Cultural Heritage Area Protection Act, introduced in May 2018.

“It doesn’t pay any attention to the existing impacts,” she said. “And we want the public health to have the same importance as profits for the oil and gas operators.”

Before her encounter with Chaco, she says she was in a lot of rejection of her Judaism.

“But now I see the draw of it,” she admitted. “Community perseverance and preservation, and the luxury to be able to get there. We’re in an instant community of shared experience. It was surprising to me how much my Jewishness was being picked up by Navajo people.”

The Navajo introduce themselves in the Diné language first by naming their matrilineal clan, then their patrilineal clan, going back to their grandparents’ clans to show how many clans they are connected to. Sobel has followed suit, to a point, introducing herself at meetings in Hebrew by reciting the names of her great-grandfathers.

“I can’t go back further than that,” she said. “But there’s a tribalism connected to the Jews I didn’t know I was connected to—instantly familial.”

Sobel hopes the fight for greater Chaco will inspire those in charge to slow down on the greediness and invest in a just transition.

“We’re at a point that we need to be having conversations based on protecting natural resources for people, like water,” she explained.

Each fracking well generally takes between 2 and 8 million gallons of water, water that is permanently removed from the water system and has to be stored somewhere as waste.

“The organizational goal,” Sobel advised, “is to get people feeling empowered and taking political action to bring on the just transition.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Frances Madeson is a freelance journalist and the author of the comic novel Cooperative Village, a satire on the war on terror set in the Lower East Side of Manhattan.