The Fighting Women of the Warsaw Ghetto

An excerpt from a new book about women in the resistance during WWII

Fifty-two thousand Jews were deported in the first Aktion in the Warsaw ghetto.

The next day, Freedom members met with community leaders to discuss a response. They proposed attacking the Jewish police—who weren’t armed—with clubs. They also wanted to incite mass demonstrations. Again, the leaders warned them not to react hastily or upset the Germans, cautioning that the murders of thousands of Jews would be on the young comrades’ heads.

Now, in the face of such mass killing, the youth movements felt that the adults were being outrageous in their overcautiousness. Who cared if they rocked the boat? They were shipwrecked and sinking fast.

On July 28, Zivia and her fellow youth group leaders all met at Dzielna.

There was no more discussion.

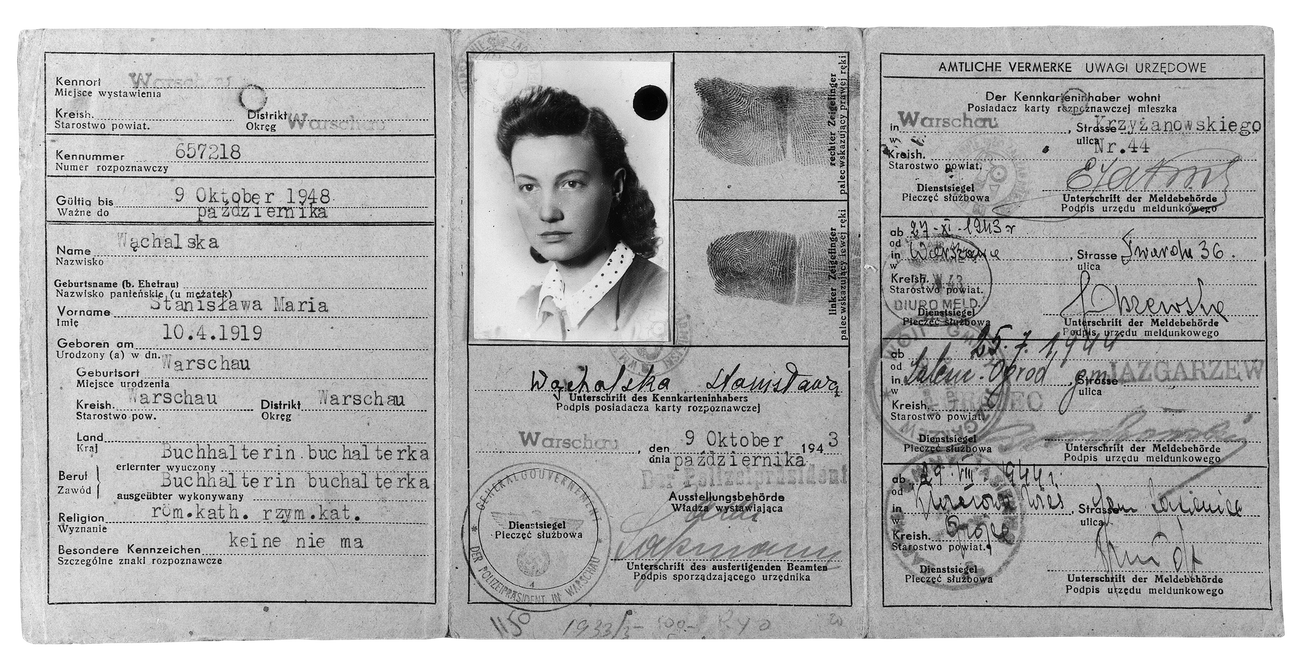

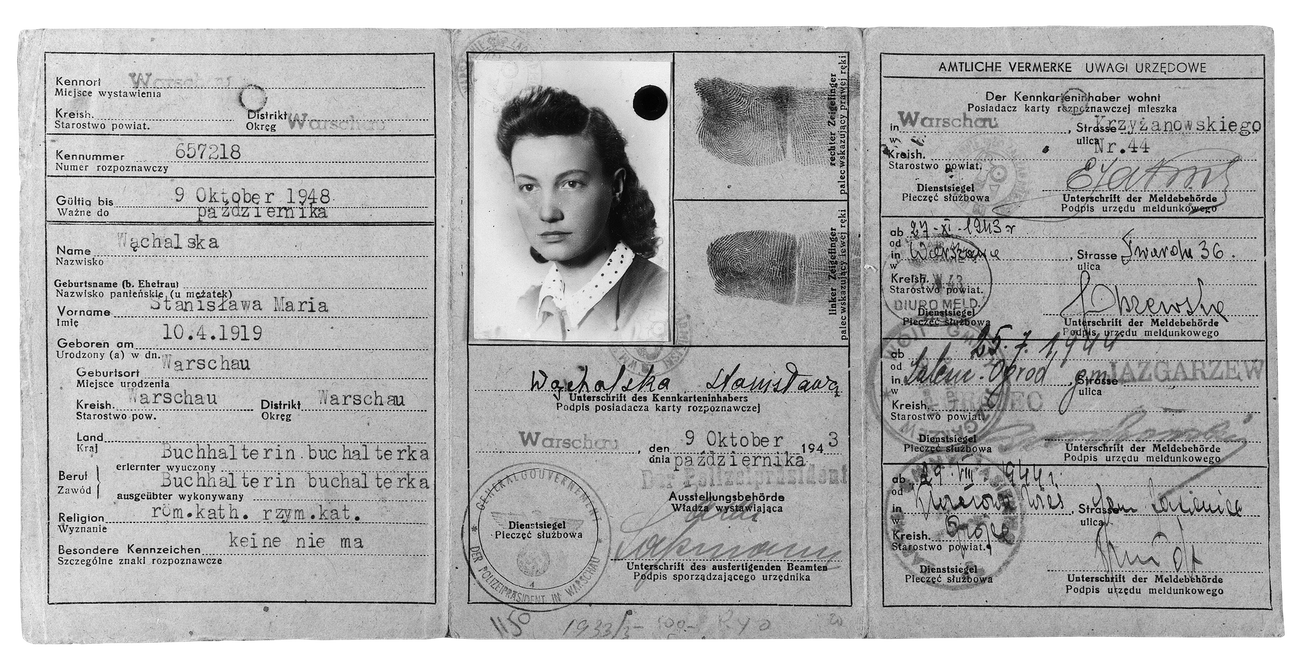

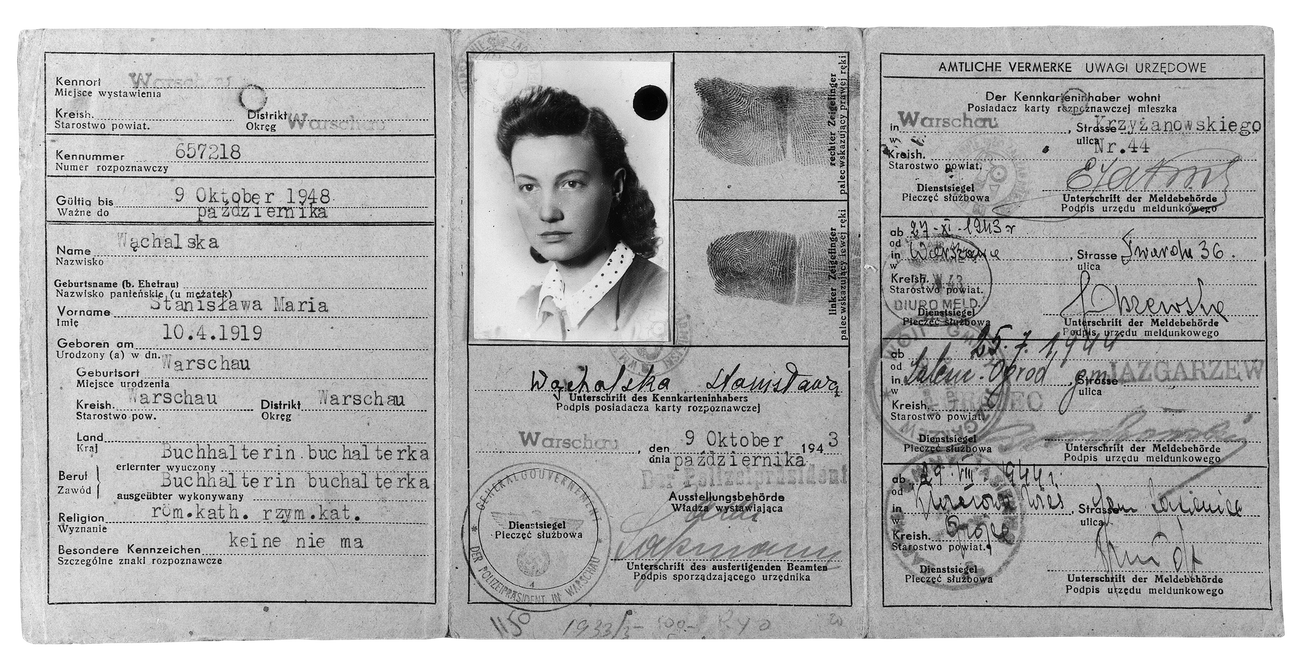

Without the adults or the Polish resistance, they established their own force: the Jewish Fighting Organization. In Yiddish: Yiddishe Kamf Organizatsye. In Hebrew: EYAL. In Polish: Zydowska Organizacja Bojowa, or, the ZOB. The ZOB was no powerhouse. It had no money, no weapons besides those two pistols, and, for the Freedom contingent, not even a local hiding place. (The group hid 140 members at a farm.) Regardless, they had a vision: to stage a Jewish protest. They were Jews fighting as and for Jews. Theirs would be a countrywide operation carried out by the connections that Zivia had already meticulously put in place. Now she would send her young female couriers on life-risking missions, not to distribute educational material or news, but to organize preparations for defense. (Though Zivia had a false ID as “Celina,” she had to stop traveling because of her conspicuously Jewish looks.) Establishing the fighting force assuaged some guilt and anxiety—Zivia felt they could finally move forward on the right path. But with no arsenal or military training, much internal squabbling ensued over how to proceed; the tension mounting as more Jews were taken away to be slaughtered.

Zivia was the only elected woman leader in the ZOB. She was part of a fighting group. She learned to use a firearm. She trained to be on guard duty. She also cooked, laundered, and was responsible for maintaining the young fighters’ optimism and spirit. Other women leaders—Tosia, Frumka, Leah—were sent to the Aryan side to forge ties and procure weapons.

While they waited for arms, the ZOB decided to mark its territory. One night, from its headquarters opposite Pawiak Prison, members headed into the ghetto silence on their first missions, divided into three groups. One group was going to inform the ghetto inhabitants about this new force that would fight on their behalf. They were to put up posters on billboards and buildings explaining that—as they had learned from messengers who had followed the trains—Treblinka meant certain death, that Jews must hide, and the youth must defend themselves. “It is better to be shot in the ghetto than to die in Treblinka!” the slogan read.

The second group was to set fire to abandoned homes and warehouses of looted goods. The Nazis had specialists assess the deported Jews’ possessions, then forced the living to rigorously organize the valuable ones.

The third group was going to commit murder. One of their double agents, a young man named Israel Kanal who was in the resistance and also working undercover in the militia, was to gun down the chief of the Jewish police. The ZOB wanted vengeance, but also to spread fear among the militiamen who were enforcing the Nazis’ edicts.

Zivia was part of the second group. Her heart beat wildly in the dark. Her sweaty palms gripped the ladder as she climbed up rung by rung, the brick of the building brushing her side. A few more steps, and she had scaled the wall, reached her destination.

She and her comrades laid down the incendiary material. But something went wrong. The house didn’t catch fire. They decided quickly to pile up all the flammable contents and set those on fire instead. “Success!” she later noted. “The flames swept into a great blaze and crackled in the night, dancing and twisting in the air. We rejoiced as we saw the reflection of the revenge that was burning inside us, the symbol of the Jewish armed resistance that we had yearned for, for so long.”

Everyone met up at 34 Dzielna Street a few hours later, all three missions having been accomplished; even the Jewish police had been afraid to take down Kanal after he shot the chief of police but failed to kill him. Then, that night, the Russians, bombed Warsaw for the first time. For Zivia, it was a night of pure elation.

And then, a wonder. By late summer 1942, one leader snuck five guns and eight hand grenades from the Aryan side into the ghetto. Tosia used ZOB money to purchase several hand grenades and guns, transported in boxes of nails. Frumka, some say, was the first to bring in weapons; she blended in with a returning labor group carrying a large sack filled with potatoes—and underneath, guns. Vladka, who was approached by a fellow Bundist and asked to work on the Aryan side, became a major weapons source, eventually transporting dynamite into the ghetto’s makeshift weapons lab. The smugglers climbed over the ghetto wall themselves or paid off a Polish guard to whisper a password to a fighter on the inside who would climb up and grab the package. They also brought in weapons through the windows of the houses that lined the ghetto border. Each addition to the arsenal brought ecstasy. Next, plans began for an ambush on the Germans. They would hide in building entrances, attack the Nazis by throwing grenades and then, in the confusion, steal their guns.

The joy of success, however, was curtailed by a new series of setbacks. Instead of jumping on board with the ZOB’s accomplishments, Jewish Warsaw was frightened by its actions. So pervasive was the community’s fear and paranoia that many assumed the recent acts of rebellion were merely German ploys, and that they were being set up to be punished. Jews were pleased to learn that someone had tried to assassinate the Jewish police chief; but they attributed the attempt to the Polish resistance, not believing that their fellow Jews had the strength or courage. Zivia was horrified to see anxious Jews tearing down ZOB posters and beating up comrades who tried to put up more.

Many fighters had been sent out of the ghetto to partisan groups in the forest, where they would be better armed, but most were killed on the way. Then a Young Guard leader, Josef Kaplan, was captured at a weapons storage site and killed. Another beloved leader went to rescue him; he, too, was caught and shot to death. Despondent, the group decided to move its cache to Dzielna. Regina Schneiderman, a young female member, put their weapons in a basket and set out, only to be stopped in the street by German soldiers, who found the arms. (As Antek later reflected: “You can imagine the size of our ‘armory’ if a girl could carry it in a basket.”) This trilogy of tragedies was “a stunning blow,” Zivia said. The group lost morale, commanders, and its plans.

The ZOB continued to debate: Should they fight immediately or strategize carefully? The talk was ceaseless. Meantime, in three Aktions carried out over three months, three hundred thousand Jews were transported from Warsaw to the gas chambers at the Treblinka death camp, and 99 percent of the children from the Warsaw ghetto were killed. It appeared that there would be no Jewish future. The sixty thousand people left within the ghetto walls were unable to look one another in the eye because they had remained alive, Zivia later wrote.

On the last night of the Aktion, September 13, a few dozen comrades sat together at 63 Mila Street. The ones who were riled up, hungering for a hotheaded response, were sent to a different room. The older members, those in their mid-twenties, stayed to discuss what to do next. Conversation was despondent. “We came together and sat,” Zivia wrote, “mourning and bleeding.” Consensus was that it was too much, too late; they were too traumatized. It was time for a group suicide mission. They would take the petrol, kerosene, and single gun that they had left, and set fire to German warehouses, shoot some Nazis, and be killed, but with honor.

Zivia, a pessimist, was outspoken: it was time to die.

It was Antek who spoke up against his colleagues, and his love. First in a whisper, then loudly: “I reject the proposal … The crisis is great, and the shame is great. But the proposed act is an act of despair. It will die with no echo … It is an act that is good for each of us on a personal level, because under such circumstances, death can appear as salvation. But the strength that has held us until now and motivated our activity—was it only in order to allow us to choose a beautiful death? Both in our fight and in our death, we wished to save the honor of the Jewish people … We have a legacy of countless failures, and we shall have a legacy of defeats. We have to start all over.”

His words clashed with the fighters’ moods, arousing incredible anger—he was stalling their only chance. But eventually those who craved a drastic-heroic act couldn’t refute Antek’s logic, and the mass suicide plan was abandoned. The comrades had to stand tall with weapons in their hands and go fight, Zivia knew. Their movement, above all, believed in the collective over the individual. From now on, resistance was the raison d’etre. Even if it killed them.

Zivia got to work gluing the movement back together for its next phase: a militia.

From the book The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos by Judy Batalion. Copyright © 2020 by Judy Batalion. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Judy Batalion is the New York Times bestselling author of The Light of Days: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos, which won a National Jewish Book Award, as well as White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood, and the Mess in Between.