The Frankfurt Lehrhaus of 1920, and Why We Need It a Century Later

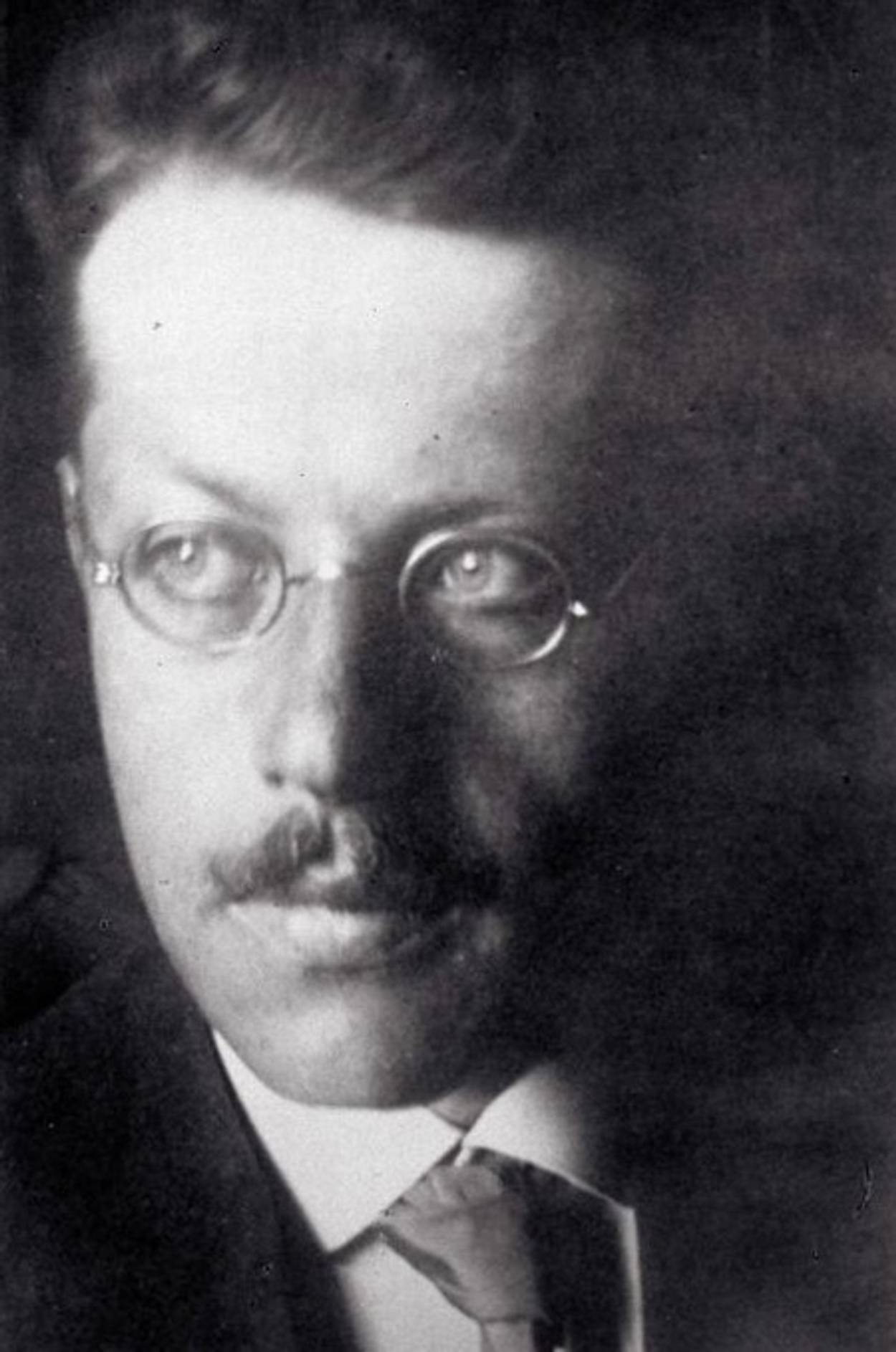

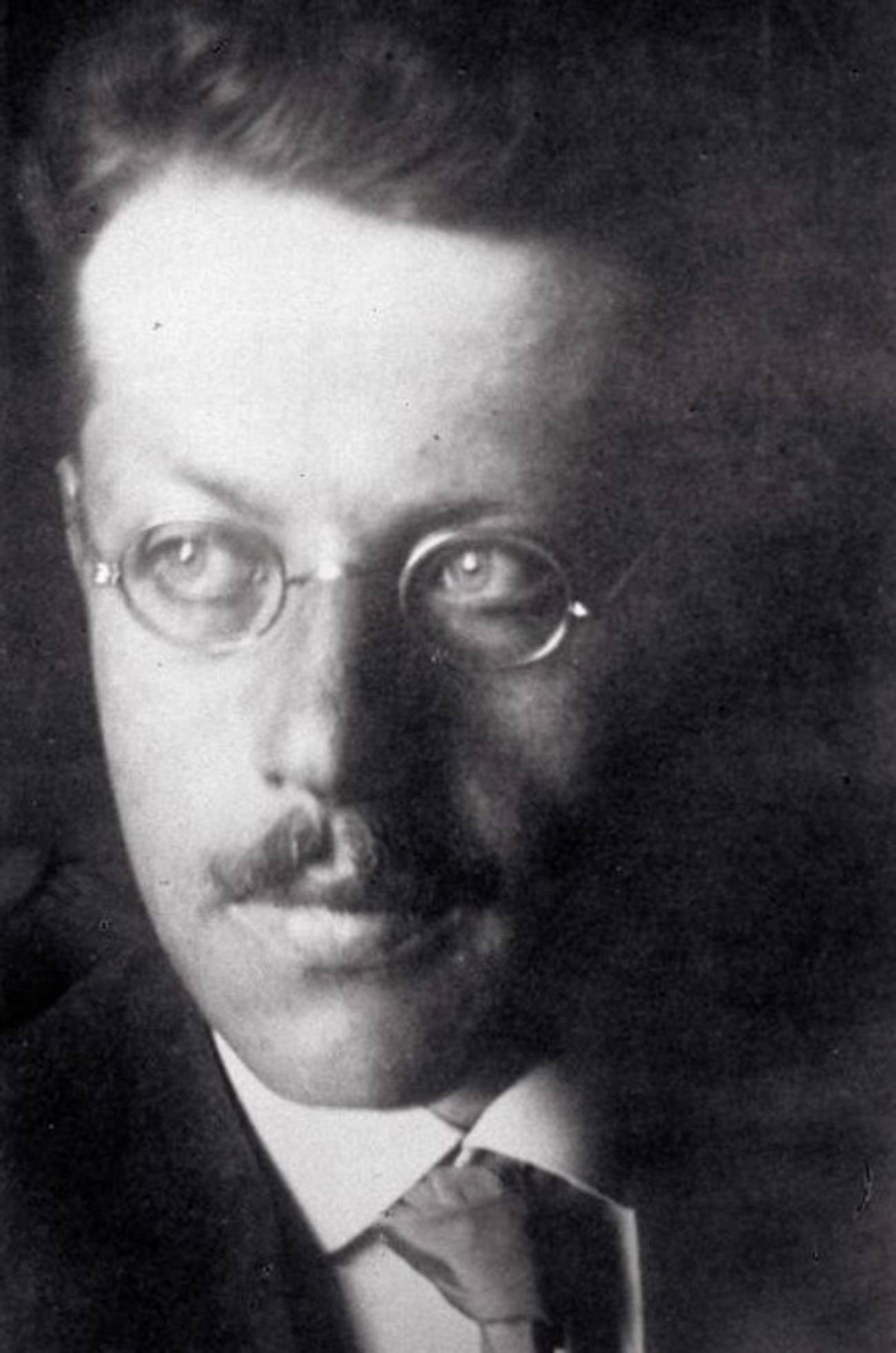

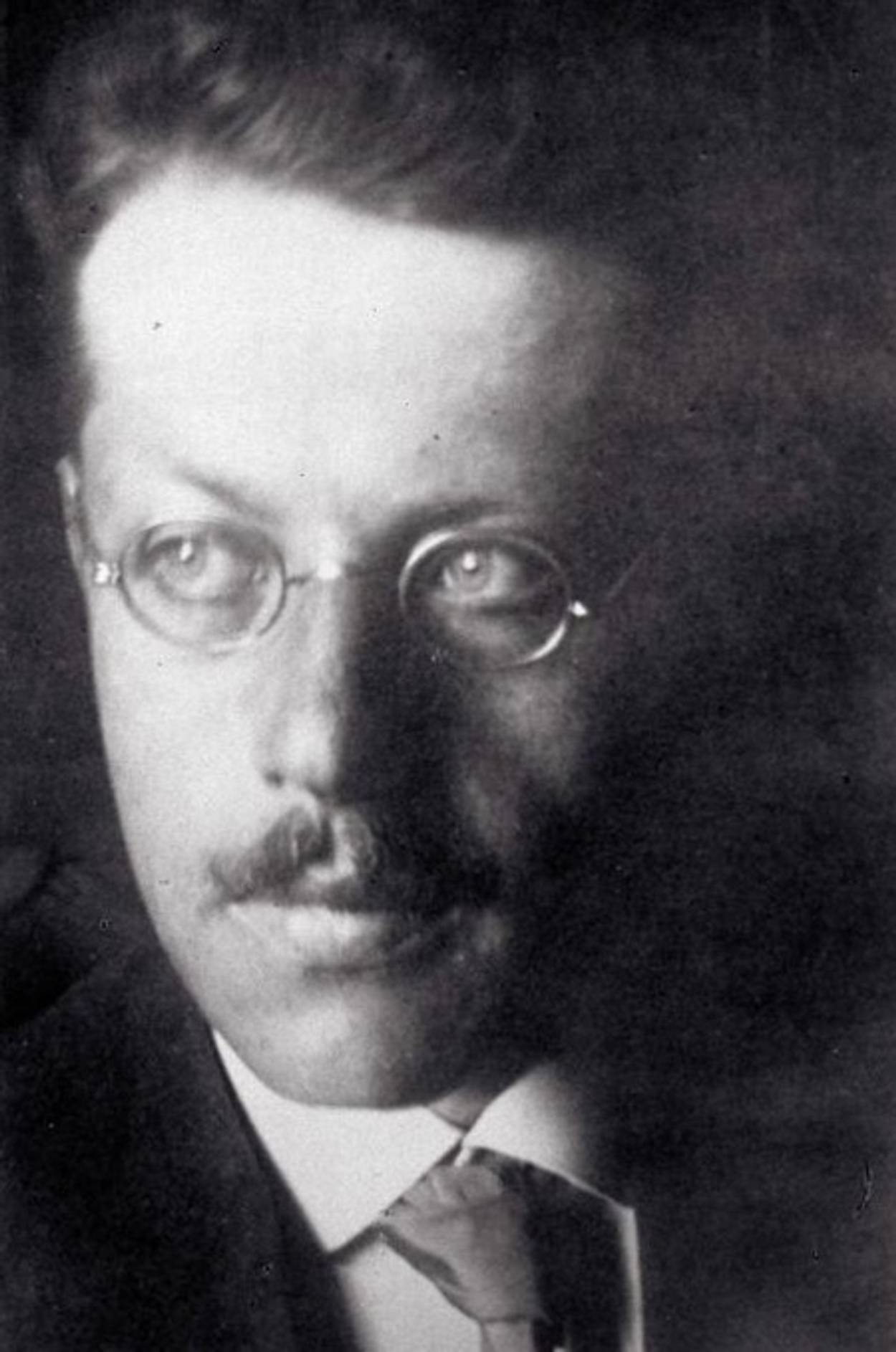

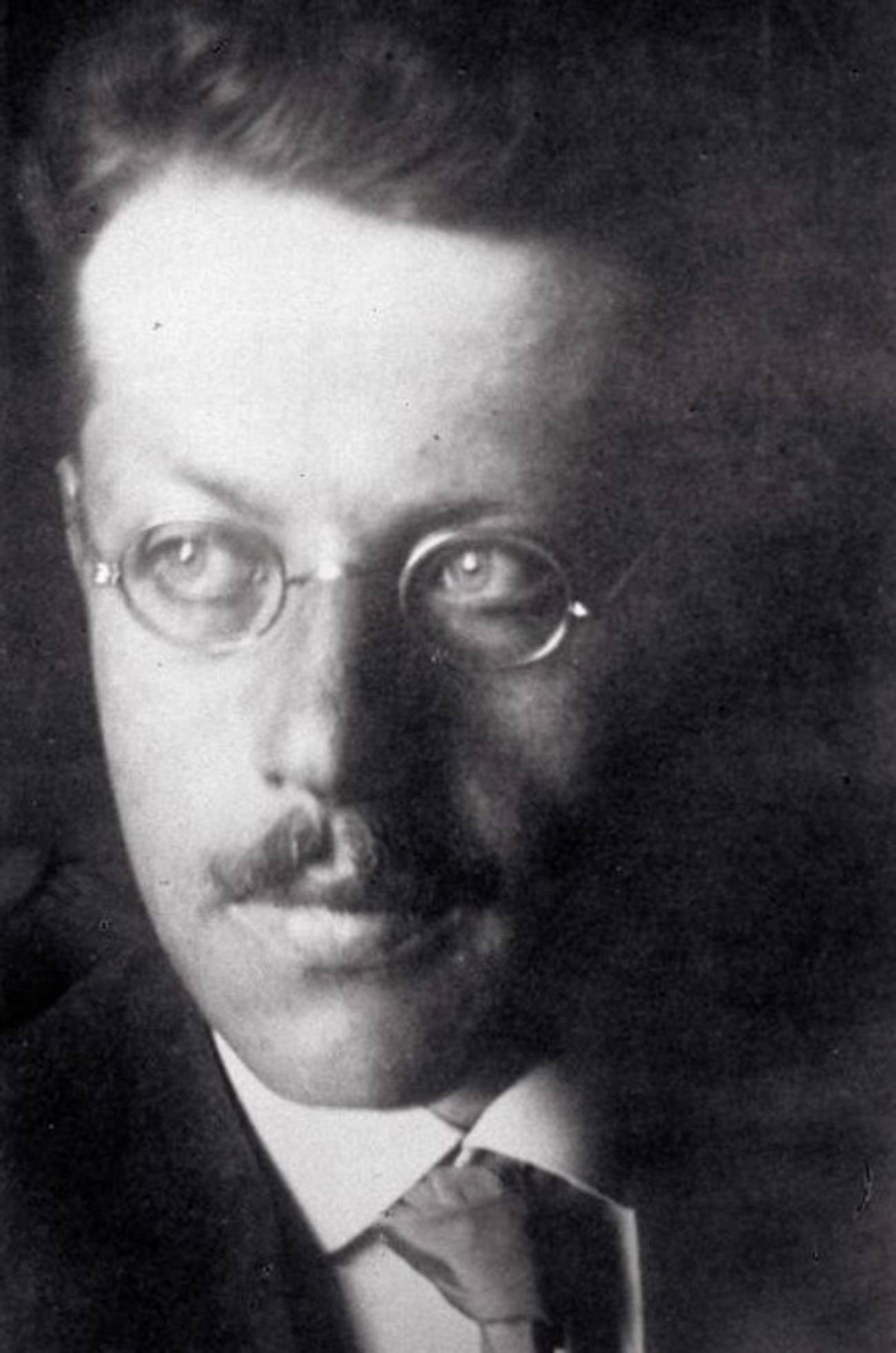

Franz Rosenzweig had the best idea you’ve never heard of

Franz Rosenzweig had completed his doctorate and was on the brink of converting. Raised in an assimilated home, he was planning to follow in the footsteps of friends who had abandoned Judaism for Christianity. In the fall of 1913, however, he opted to deepen his Judaism rather than fulfill his original plan of conversion. With the coming of war, he served in the kaiser’s army. In the trenches, the thinker began writing (on postcards!) what would eventually become his classic, The Star of Redemption, a synthesis of his German and newfound Jewish commitments and a new model of Jewish identity.

This oft-told story features a young intellectual seeker who, at the last minute, swerved away from the baptismal water, stayed within the Jewish fold, and wrote seminal works of Jewish thought. What’s far less considered is how, after encountering Eastern European Jews on the war front and surviving WWI and the 1918 influenza pandemic, the newly minted war veteran made a wild—and practical—intervention in German Jewish life. He eschewed academia and devoted himself to enlightened Jewish spiritual renewal by inaugurating a new kind of adult Jewish learning institute. The reverberations of Rosenzweig’s vision of learning for assimilated Germans like himself can still be felt in Jewish life today. His spirit can be found in numerous contemporary Jewish institutions, practices, and lives, and an appreciation of concepts and practices he pioneered can deepen Jewish life in 2020 and beyond.

The Freie Jüdische Lehrhaus, or Free Jewish House of Learning, launched 100 years ago this year, when Rosenzweig joined with collaborators in Frankfurt and developed an educational institution, and a practical model, meant to speak to Western Jews who were strangers, not “natives,” to Judaism. This Lehrhaus, or house of learning, a revamped beit midrash tailored to assimilated Jews, met in community buildings and rented halls. It lacked modern precedent. The educational experiment riffed on ideas emerging in Weimar Germany concerning adult education, as it synthesized critical academic study of Judaism with Talmud Torah (Torah study), toward a revitalized practice of adult Jewish teaching and learning. Here, Jews ignorant of, and alienated from, Jewish life and tradition acquired knowledge and understanding of Judaism and explored Jewish identity, on their own terms.

As one who underwent a process of dissimilation, Rosenzweig understood the zeitgeist, in which functionally secular Jews struggled to engage with traditional religion. He rejected the status quo, expanding on and redefining the conventional model of Jewish education. He disrupted the existing adult Jewish learning field by centering text study and blurring boundaries between teacher and student. Moreover, this was, as he said at the institute’s inauguration in 1920, “a learning that no longer starts from the Torah and leads into life, but the other way round: from life, from a world that knows nothing of the Law, or pretends to know nothing, back to the Torah. That is the sign of the time.” A new vector for pedagogy signaled openness to innovative, creative engagement. The game had changed for good.

Rosenzweig’s principle of “learning in reverse order” resulted in counterintuitive hiring practices. Largely assimilated, Jewish and Jew-ish characters from the German intellectual and cultural scene, often with limited Jewish knowledge, taught Judaism-related subjects. For example, Eduard Strauss, the renowned chemist who offered a popular Bible course, knew no Hebrew and taught in German translation. The Lehrhaus gave recognized and rising intellectual stars (many of whom merely happened to be Jewish by birth) a stage on which to share their thinking on Jewish texts and ideas. The faculty roster, which encompassed physicians and politicians, artists and chemists, authors and activists, and even some rabbis, reads as a who’s who of early 20th-century German (and European) Jewish minds and culture-makers: Martin Buber, Ernst Simon, Nehemiah Nobel, Gershom Scholem, Leo Strauss, Bertha Pappenheim, Erich Fromm, S.Y. Agnon, Marc Chagall.

Among the 27,000 Jews living in Weimar Frankfurt, the school had far-reaching appeal. One semester, the school enrolled 1,100 students, in courses including Hebrew language, Bible, Near Eastern history, and Jewish thought. But despite initial success, the Frankfurt Lehrhaus only ran from 1920 to 1926. After Rosenzweig contracted what would later be called Lou Gehrig’s disease, a suitable successor could not be found, and the institution faded. Nevertheless, the model had wings. After 1920, institutions called Lehrhaus had cropped up in Mannheim, Stuttgart, Hanover, Cologne, Nauheim, and Wiesbaden, joining the one in Frankfurt, as well as preexisting Volkshochschulen, Jewish adult education institutes, in Berlin and Breslau.

In the 1930s, Buber and later Heschel led a revitalized iteration of the Frankfurt Lehrhaus, which spiritually sustained local Jews when their dignity was being undermined. After WWII, the Lehrhaus lineage took different forms, and each testified in its way to the original. Nahum Glatzer, an early instructor at the Lehrhaus who became a Brandeis professor, conveyed the institution to an American audience; in the 1960s, students of his were among the founders of the Boston-area community Havurat Shalom. On the West Coast, Fred Rosenbaum and fellow Bay Area academics and community leaders founded Lehrhaus Judaica (renamed Hamaqom) in 1974. More recently, in 2016, Orthodox scholars and activists created an online forum, TheLehrhaus.com, concerning the past, present, and future of Judaism, and Orthodoxy in particular.

Today, everywhere that Jews learn outside of a traditional yeshiva context, they are embodying the Lehrhaus spirit. It materializes at Limmud, the global producer of conferences, which seeks to facilitate democratic, nonhierarchical Jewish learning communities. It appears in emergent congregations, such as IKAR, The Kitchen, and Romemu, which affirm liberalism in their adoption, adaptation, and tailoring of Judaism. It surfaces at batei midrash like Hadar, Svara, Bina, Alma, and Paideia, which, in their own ways, center Jewish texts and ongoing hevruta with Jewish sources, toward aims of personal meaning and relevance.

Rosenzweig’s thinking courses through the veins of and animates such institutions, whether people there know it or not (most likely don’t). Nevertheless, there is more we, and they, can glean from the original incarnation of Lehrhaus, back in 1920. Rosenzweig knew some things we would do well to learn anew.

First, Rosenzweig would say that more chemists should teach Bible today, so to speak. Put another way, Bob Dylan and Masha Gessen and Bernie Sanders and Aly Raisman and Michael Sandel and Bari Weiss and Tony Kushner and Tiffany Haddish and Elena Kagan and Gal Gadot and Mark Zuckerberg (and so many others) should teach us Torah. Our best minds and our recognized leaders, those who may be deemed “peripheral” to or “ignorant” of traditional Jewish life, can be authorized as Jewish educators. Rosenzweig’s mantra of “learning in reverse order” can lead to recognition of and appreciation for the depth of secular involvement of our contemporaries (and ourselves)—and engender novel possibilities for fresh exploration of Jewish sources.

Second, Rosenzweig would claim that we ought to pursue existentially conscious, experiential, holistic learning over either detached, intellectual knowledge or parochial Talmud study. In the domains of Jewish learning and scholarship, these are notable suggestions. The Lehrhaus, as a worldly institution of higher education, embodied an alternative to the contemporaneous German research university model and the traditional yeshiva. In this vein, it sought to expose people to sources of transformation and to attune people to possibilities of learning beyond both narrow scholasticism and dense abstractions and theory.

Third, Rosenzweig would assert that, as Jews, we are neither objects of nor castaways of tradition. He implored, 100 years ago, “Turn into yourself, return home to your innermost self and to your innermost life.” In the shadow of Rosenzweig’s 11th-hour return to Judaism and the model of the Frankfurt Lehrhaus, we can take part in an ongoing reimagination of Jewish tradition and education. We can reclaim and recreate tradition in our time, by learning from texts, teachers, peers, students, the world, the divine, and ourselves, and enacting such learning in study houses, on the streets, and beyond. Revised, Lehrhaus-inspired educational models in this 21st century can endow us, as initiates and innovators of tradition, with roots, offer us community, and galvanize us to renewed purpose.

Joshua Krug is the Sommerfreund Visiting Professor of Jewish Studies at the Hochschule für Jüdische Studien.