From a Number to a Name

Tracking down the identity of an anonymous Auschwitz prisoner

The man in the photograph has a pleasant face, open and ordinary, clean-shaven with a broad forehead and close-cropped hair. He stands at a workbench strewn with hammers, pliers, and clamps, eyes focused on the screwdriver in his hand, gingerly working some mechanical box.

He does not appear malnourished or abused, certainly not for a concentration camp prisoner. Grime blackens his fingers and nails, as it does his striped camp jacket.

A patch on the jacket depicts a Star of David and, if you zoom in a bit, a number: 177242.

The photo had been floating around the internet for decades, just another anonymous victim of the Holocaust, identified only as an inmate of the Blechhammer labor camp working at an electrical workshop.

My late father, Josef Lajtner, had also been an inmate at Blechhammer, and he also had a number: 177904. He spent 19 months there working as a welder. Because of this vague connection to my father’s past, I had downloaded the photograph from the Yad Vashem archives some 15 years ago.

Yad Vashem had no further information about the photo’s provenance, other than it belonged to one of its very early collections. “Many of those early photographs do not have additional information due to lack of proper cataloging, the various sources they come from, and the general chaos which characterized this period,” said Emanuel Saunders, a spokesman for the photo archive.

With nearly 4,000 prisoners, Blechhammer was the second-largest labor camp, and the largest exclusively Jewish camp, in the Auschwitz archipelago of 40 camps. The prisoners were part of a 40,000-man workforce building Blechhammer North, a synthetic refinery tasked with converting coal into gasoline and fuels for the German war machine.

In researching my father’s timeline through the war, I had also visited the site of Blechhammer camp, about 35 miles from Auschwitz near what is today the Polish town of Kedzierzyn-Kozle. There I met a group of local Polish history buffs, the “Blechhammer 1944 Association,” dedicated to maintaining the region’s history during the war. Their focus is mostly on the U.S. 15th Air Force’s six-month bombing campaign against the Silesian refineries, including Blechhammer.

Over the years, the group has helped track down remains of missing American airmen shot down over the area. In 2019, they completed a yearslong conversion of a derelict air raid shelter into a museum with artifacts from the air campaign and the many POW and labor camps that dotted the area.

One member of the group, Edward Haduch, began to seriously research the Blechhammer Forced Labor Camp for Jews, motivated, he said, by “my deep conviction that the inmates of the camp need to be honored and remembered, and the knowledge that my town is not widely recognized as a significant place on the map of the Holocaust.”

Haduch and I have been exchanging tips and leads for years. With some funding from the local community council, he organized an exhibit about the Jewish camp at the town library. As part of the exhibit, he enlarged the photograph of Prisoner 177242 to poster size. The Auschwitz Museum loaned the exhibit a replica of the blue-gray striped concentration camp uniform. For added realism, it put the number from the poster on the pajama jacket, just like in the photo.

When Haduch told me of his plans a few years later, he asked if I had any way of identifying Prisoner 177242.

In January 1945, reeling from the Red Army winter offensive, Himmler ordered the evacuation of 66,000 prisoners from Auschwitz and its subcamps on what became a series of death marches deeper into Germany. The order vaguely specified that no prisoner fall into the hands of the Russians. Interpretation was effectively left to the SS guards accompanying the prisoner columns. They weren’t called the Death’s Head Division for nothing.

On Jan. 21, some 6,000 of those prisoners left Blechhammer on a 12-day, 180-mile forced march through driving snows and subfreezing temperatures to the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, the designated destination for tens of thousands of evacuees. At least 800 were shot or otherwise died along the way.

Three transport lists survived the war with the names of 6,439 prisoners who were loaded onto open railcars and shipped 300 miles from Gross-Rosen to Buchenwald in February 1945. But it’s the lists themselves that are a marvel of Nazi bureaucratic efficiency even at a time of retreat, chaos, and collapse of the German military.

Each is first divided by nationality—French, Polish, Dutch, Hungarian, Greek, Czech, Russian, and so on. Each nationality is then subdivided into “politicals” and “political Jews,” with some insertions for “mixed race.”

Within each subcategory, names are in alphabetical order. Each typed, single-spaced line is numbered and records the prisoner’s new Buchenwald ID number, last name, first name, date of birth, place of birth, work assignment, and the registration number of his previous camp.

Thanks to the efficiency of the SS, it had taken me only five minutes to find my father’s name on line 1,945, page 33 of the 56-page List II, under “Polish Political/Jews,” after I had first received the lists in 2008, courtesy of the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

So when Haduch asked me some years later to help identify Prisoner 177242, I turned to the death march lists.

Searching line by line, I found him under “French Political/Jews,” line 2,044, page 35 of List I: Jean Grynberg, born Feb. 9, 1904, in Brest, then part of Russia. His job is listed as electrician, just as the Yad Vashem photo had identified him.

I had put a name to a number.

From other Yad Vashem archives, I learned that Grynberg was an engineer and had moved to Paris before the war with his wife, the former Yocheved Bergerman, originally from Bialystok. The couple had one son, Claude, born in 1931.

An archival database of 70,000 French Jews deported to Auschwitz provided more details. The Grynbergs had been seized by Vichy French police collaborators from their Paris apartment at Boulevard Jourdan 32. Today, a pizza and pasta restaurant occupies the ground floor of the six-story neoclassical limestone building.

The Grynbergs were sent to the Pithiviers transit camp, about 55 miles south of Paris. Jean was kept in Barrack 16, separated from Yocheved and Claude, in Barrack 10.

On Sept. 21, 1942, they were among 1,051 men, women, and children sealed in cattle cars that became Transport 35 to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

“The moaning and crying never stopped,” recalled Robert Widerman, who was on Transport 37 from the Drancy transit camp five days later. “More than anything I remember the unbearable stench. The [waste] buckets had no lids. They filled up very quickly and there was no way to get rid of the defecation.”

After the war, Widerman changed his name to Robert Clary and became the actor best known for his role as Frenchie (formally, Cpl. Louis LeBeau) on the TV sitcom Hogan’s Heroes. He recounted his experiences as a concentration camp prisoner and the death march in his 2007 autobiography.

Grynberg’s Transport 35 was stopped at the small railway station of Cosel, about 30 miles from Auschwitz. He and some 150 men were ordered off the train and sent to local labor camps. Yocheved and Claude, then 11, were gassed on arrival at Auschwitz. Of the 1,051 Jews on Transport 35, only 29 are known to have survived the war.

Robert Clary’s Transport 37 was also stopped at Cosel, and he and 175 men removed from the train. When the train arrived in Auschwitz, another 131 men and women were selected for work. The remaining 698 men, women, and children were sent to the gas chambers.

Of the 1,004 people on Transport 37, only 15 men are believed to have survived the war. None of the women did, not Clary’s mother, not his sister.

Though Grynberg and Clary couldn’t have known it, they were saved from Birkenau and likely death because of competition between two SS bureaucracies for able-bodied workers.

In 1942, Blechhammer had not yet been absorbed by Auschwitz, which was part of the Concentration Camp Directorate under Oswald Pohl. Instead, Blechhammer was run by a separate bureaucracy headed by SS Gen. Albrecht Schmelt. Commonly known as the Organization Schmelt, it operated some 100 labor camps and controlled more than 50,000 Jewish workers in the region.

Though both Pohl and Schmelt ultimately reported back to Himmler, both were also in the business of renting out cheap labor to German industry, which increasingly was being stripped of its German civilian workforce by the war.

Over several months, Schmelt removed nearly 10,000 able-bodied laborers from transports of Dutch and French Jews destined for Auschwitz.

Schmelt’s actions outraged Auschwitz Kommandant Rudolf Hoss.

“These men on their own authority, without informing anyone, and without orders from the Reich’s Security Office, stopped the transport trains to Auschwitz,” Hoss wrote from his prison cell after the war. “They took healthy Jews from the trains and exchanged them for their disabled workers or even dead ones … This continued until my complaints moved the higher SS and police leaders to put an end to it.”

Both Jean Grynberg and Robert Clary ended up in Blechhammer.

It wasn’t until April 1, 1944, that Blechhammer was absorbed by Oswald Pohl’s Concentration Camp Directorate. Only then were prisoners tattooed with Auschwitz numbers and exchanged their civilian clothes for blue-and-gray striped concentration camp uniforms.

That means Jean Grynberg had been a forced laborer for nearly two years when the photograph was taken sometime after April 1944. Yet even a cursory examination of the photo confirms some universal truths about survival in the labor camps.

The first goal of survival was to become classified as an “essential” worker. An engineer like Grynberg, or a welder like my father, would have made the cut. This qualified them for more food, about 1,700 calories a day, compared to 1,200 calories for “unskilled” laborers.

A second goal was to get assigned to indoor work, out of the harsh winters that sapped a man’s strength and diminished any chance of survival.

Prisoner 177242 checked both boxes: an electrician working indoors.

However 1,700 calories was still far below the 2,500 required by an average man doing physical labor. Grynberg’s relatively good physical appearance in the photograph indicates he had achieved the third, and perhaps most critical, goal for survival: He had learned how to “organize” more food, which could mean anything from theft to black market trading with British POWs and foreign contract workers at the construction site.

Then came the Russian offensive and the death march to Gross-Rosen. Jean Grynberg, Robert Clary, Josef Lajtner, and thousands of their fellow prisoners were given double food rations—about a pound of dark camp bread, a slice of horsemeat salami, a double measure of artificial honey—and marched out five abreast into the harsh Polish winter.

“The great terror was knowing that, despite your exhaustion, you had to stay on your feet and keep walking,” Clary recalled. “If you sat down to rest or were too weak to go on, you were shot. On the march, we heard constant rifle and pistol shots.”

Rudolf Hoss, promoted from Auschwitz kommandant to a headquarters job in the rear, was dispatched to the Eastern Front for a firsthand look after communications were cut off by the Soviet advance.

Writing from his prison cell, Hoss said, “There was no food. In most cases, the [German officers] who were leading this parade of walking dead had no idea which direction they were supposed to go … It was easy to follow the route of this ordeal of suffering because every few hundred meters lay bodies of prisoners who had collapsed or been shot.”

Gross-Rosen had done little to prepare for the arrival of thousands of prisoners as the camp’s population swelled to more than 97,000.

“Oh, I have tasted hell on Earth and I know what it is,” recalled Clary. “They did not know what to do with us. They shoved us into unfinished barracks—no windows, no doors, no bunks, no straw on the floor, just cold cement—and it’s freezing and muddy outside.”

In his memoir after the war, Walter Spitzer, then a teenager from Poland, remembered “a constant line of prisoners, pulling corpses, or skeletons more precisely, holding them by the tendons and the skin. In the total silence, the only thing we can hear is the dull sound of the skulls and the open mouths scraping on the ground.

“It’s a terrifying spectacle to see the dead carried by the half dead.”

Three days later, Gross-Rosen began shipping prisoners in open coal cars to Buchenwald.

According to the transport lists, Jean Grynberg was registered into Buchenwald on Feb. 10, 1945, the same day as Robert Clary and Josef Lajtner. They were warehoused in Buchenwald’s “Little Camp” down the hill from the main “Big Camp.” Between January and April 1945, 5,200 prisoners died in the “Little Camp.”

Robert Clary was saved by a German kapo in charge of delousing, who arranged to send Clary to the “Big Camp” and the protection of French Communist cadres who pretty much controlled their barracks.

Josef Lajtner was transported to another concentration camp on March 9, about a month before Buchenwald was liberated by Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army. He would escape from another death march and to freedom on April 21.

Jean Grynberg didn’t make it.

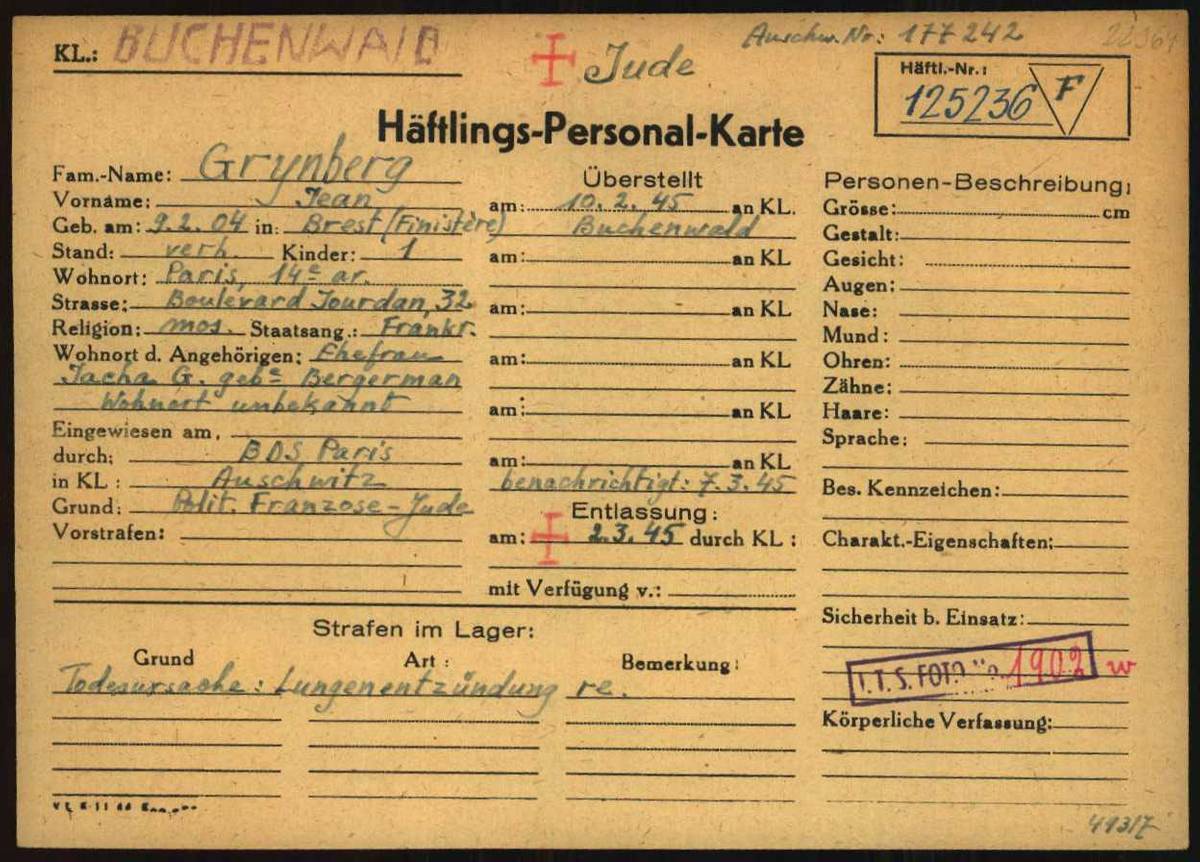

His Buchenwald Inmate Personnel Card, which had been filled out when he arrived, records he died on March 2, 1945, of pneumonia. Grynberg’s body was likely loaded onto a two-wheeled pushcart and dumped into a mass grave with thousands of other nameless victims.

Following protocol, an inmate clerk noted the death on the personnel card with two red ink crosses in the Templar style known as “Deus Vult”—Latin for “God Wills It.”

This article is part of a series for Yom HaShoah.

Mel Laytner, a former foreign correspondent for NBC News and UPI, is the author of What They Didn’t Burn: How Hidden Nazi Documents Proved a Survivor’s Holocaust Stories.