From Japan With Love

Mysterious photographs lead to some Japanese who rescued Jews from the Holocaust, with a boat, in secret

In 1998, a Japanese man named Akira Kitade, who is now 71, visited his old boss, Tatsuo Osako, for whom he had worked for decades at the Japan National Tourist Organization. As the men talked at Osako’s home in Tokyo, Osako showed him seven photographs, arrayed across two rows on a page of gray paper in an album. All the people in the pictures, Osako told him, were passengers upon the Amakusa-maru, the rickety ship on which Osako had worked as an assistant purser in 1940 and 1941. The photographs all had scribbles—a short message, a partial name, an initial, even one full name—on the backs. The images represented heartfelt thank-yous, perhaps the only presents the passengers could extend.

“It was surprisingly emotional,” Kitade said of his long-ago meeting in Osako’s living room, when we spoke by video chat in late January. “I was shockingly touched, moved. It was exciting, thinking of how Mr. Osako had kept these photos with care for such time, for 60 years. Those seven photos were so neatly preserved.”

The passengers’ three-day crossing of the Sea of Japan on the Amakusa-maru, from Vladivostok, Russia, to the Japanese port of Tsuruga, hardly qualified as a cruise; it was more like a rescue shuttle. From September 1940 to June 1941, the Amakusa-maru and other vessels ferried refugees from the Nazis to shelter in Japan. According to a nine-page memoir Osako wrote in 1995, he worked more than 20 such voyages. Kitade said Osako estimated that there were 400 passengers aboard each.

Some passengers appeared elegantly dressed and wealthy. Most looked “forlorn and lonely, like fleeing travelers,” Osako wrote, and he “felt keenly how sorrowful it was to be stateless and, in contrast, I also felt how fortunate I was to be born a Japanese.”

For years, Kitade wondered about the man and six women whose visages appeared in these photographs. Then, in about 2009, he began scratching at the mystery itching him. He began searching. Last year, Kitade met a relative of one of them.

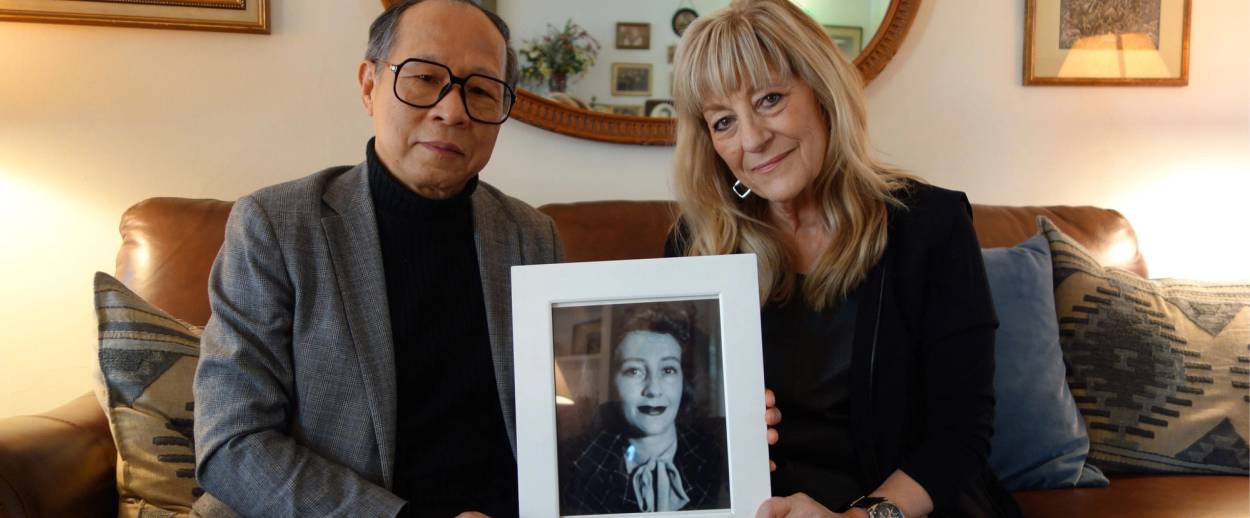

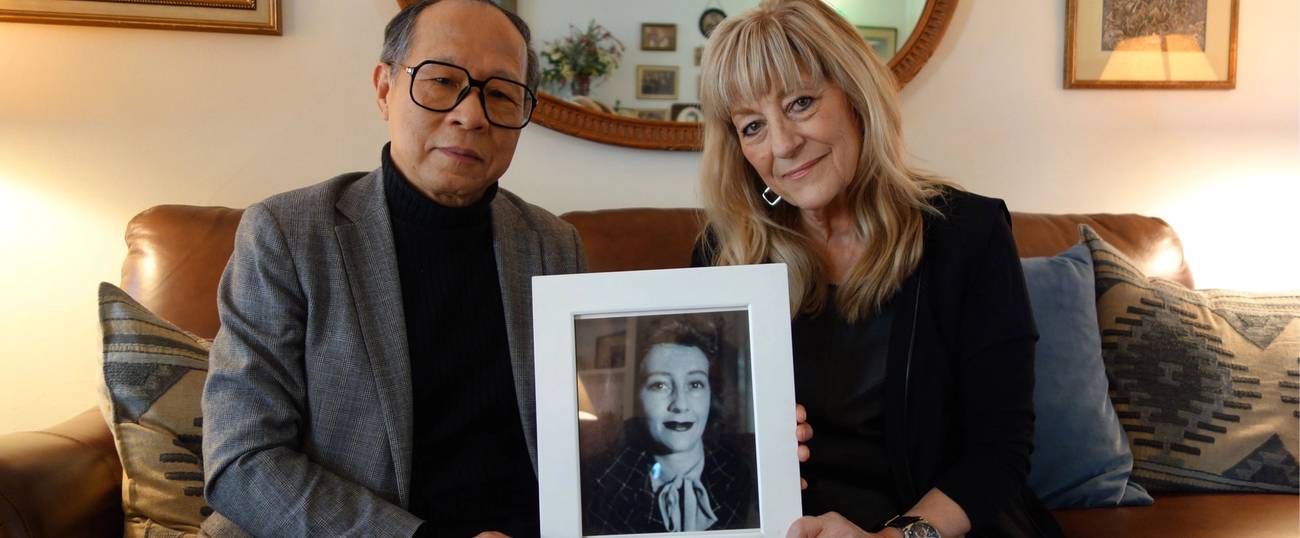

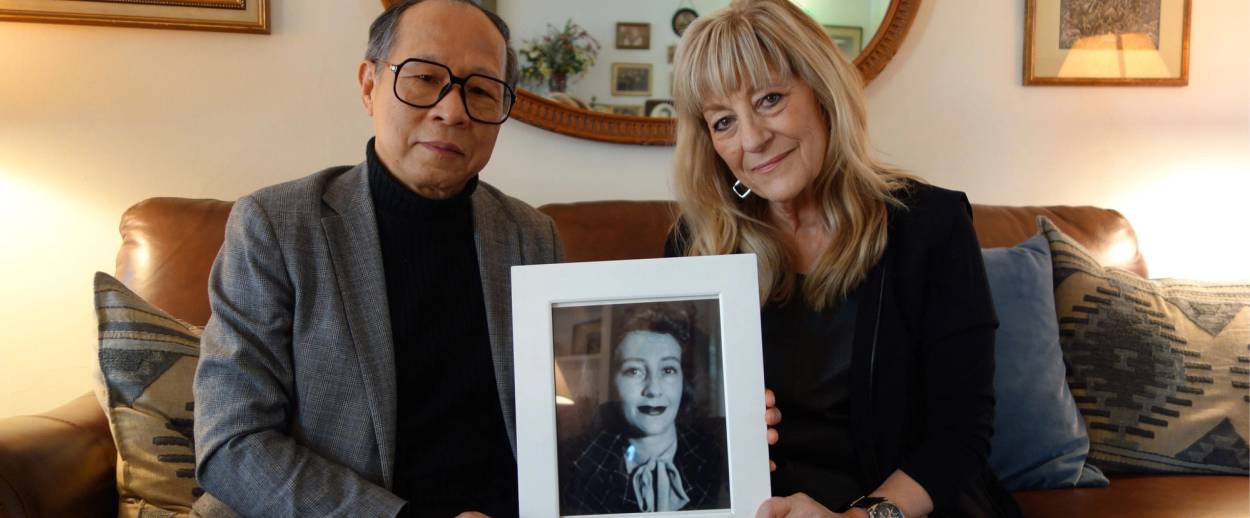

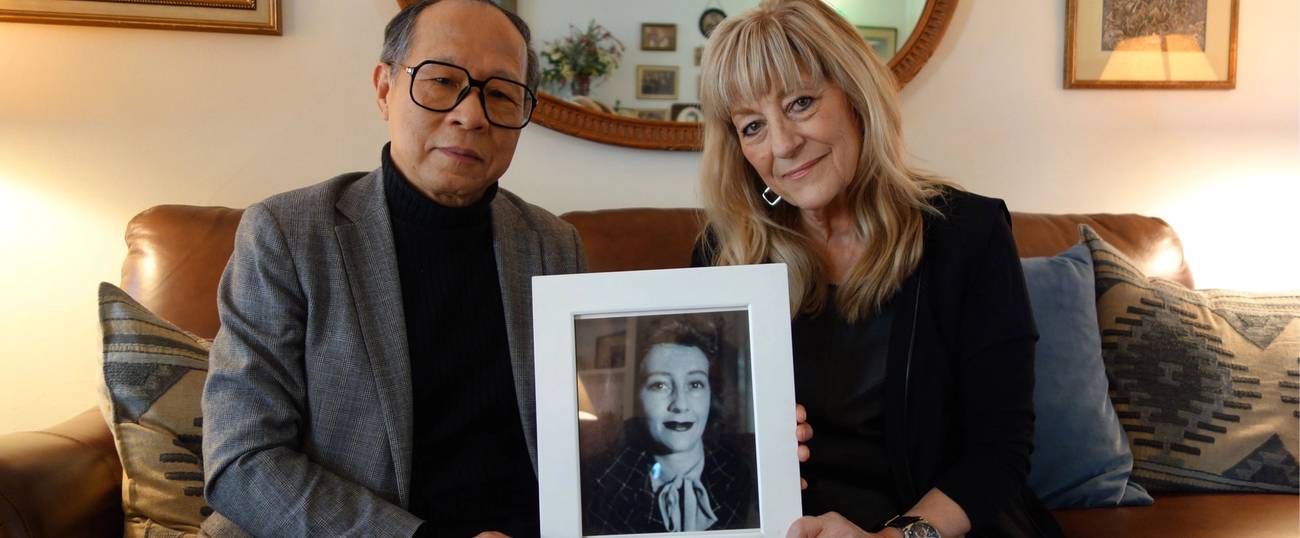

In a living room in Hartsdale, New York, a Japanese television crew noisily prepared its gear. It was early December 2015, and the TV crew had come to interview Linda Birnbach about her mother’s escape from Norway during WWII and arrival in America. From above the mantel and on the shelves behind Birnbach peered the framed faces of relatives, including her late mother, Vera Harrang. Kitade, his face sitting under large-framed eyeglasses, watched silently from a chair opposite Birnbach.

***

This incredible story reaches back beyond Birnbach; beyond her mother, who was one of the passengers; beyond Kitade, who learned of the story from his former boss Osako’s photo album; all the way to Chiune Sugihara, Japan’s consul in the Lithuanian city of Kovno. It was thanks to Sugihara that most of these passengers likely reached Vladivostok on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Beginning in the summer of 1940, Sugihara, defying his foreign-ministry superiors in Tokyo, issued what Yad Vashem, Israel’s national Holocaust-remembrance institution, later estimated to be 3,500 transit visas, with which refugees could cross the Soviet Union and reside temporarily in Japan.

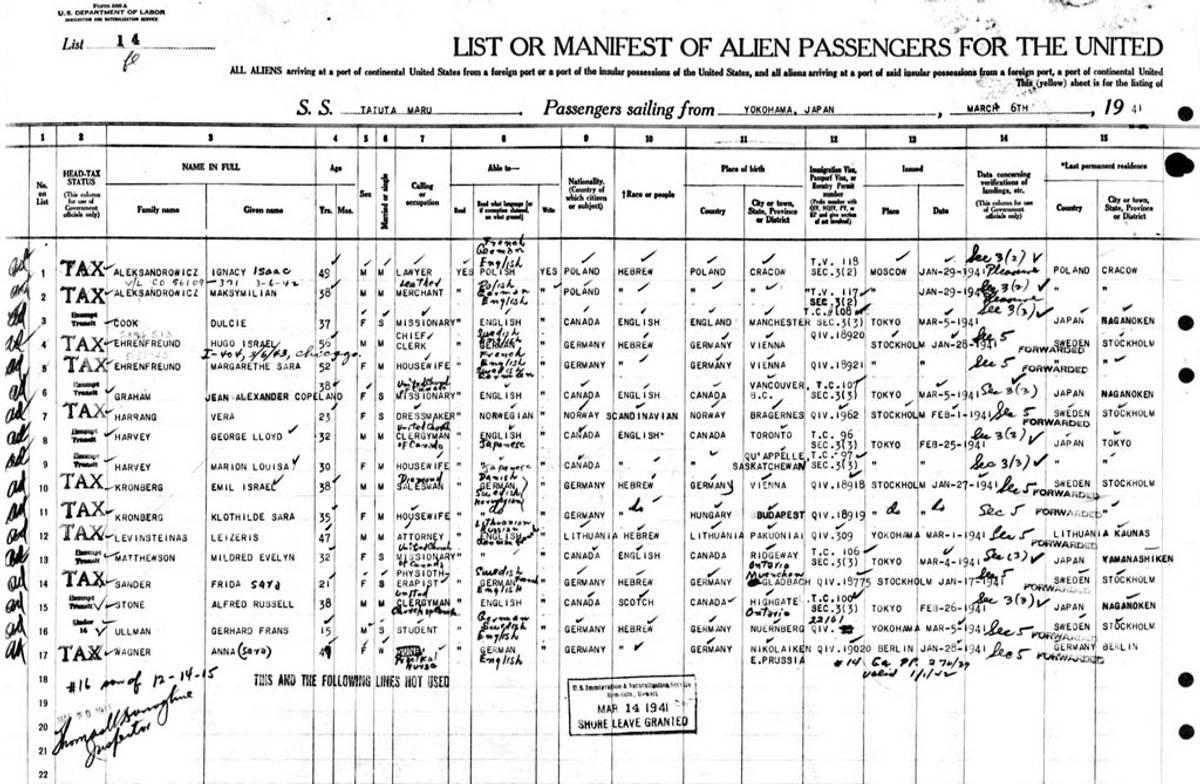

The Amakusa-maru’s staff likely didn’t know of Sugihara. The Japan Tourist Bureau, for which Osako, then in his mid-20s, worked, contracted with an American company and several Jewish organizations to handle the sea crossings. His tasks included checking names and visas against the manifest and disbursing funds forwarded for each traveler. The work was complicated, he wrote, by the pitching boat that often relegated him to bed with seasickness, particularly during winter storms.

While Sugihara, who died in 1986, became a hero in Japan, Kitade felt obligated to honor his late friend. To Kitade, Osako and his colleagues played important supporting roles by being there for the refugees and extending a human touch. The staff was “very nice to me,” recalled Nina Admoni (resident of Ramat Aviv, Israel), who was 8 years old when she and her parents rode the ship to Tsuruga after receiving Sugihara-issued visas and fleeing Vilna. “They would show me around: how the ship operates, the big wheel, the lifeboats.”

“My main theme is not Mr. Sugihara himself, but those ordinary Japanese people who supported Mr. Sugihara’s deed behind the scenes,” Kitade said in the video chat from his living room. “It’s not Sugihara himself who rescued all those Jewish refugees. There were other people who rendered the hand of help. He couldn’t do the heroism by himself.” He relied on people like Osako.

Kitade speculated that Osako, whom he described as a calm, gentle man, was repaying a debt. Osako’s grandfather, Osako Naoharu, was a general who fought in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-5. Japan’s leaders had just received a critical loan from American-Jewish banker Jacob Schiff, who might have acted, in part, because of the anti-Semitism Jews in Russia endured.

“It’s entirely thanks to this banker that Japan could win this war, so 40 years later Mr. Osako helped these Jewish refugees,” Kitade offered. “At that time, Japan could repay Jacob Schiff’s generosity.”

***

To better grasp his countrymen’s heroism, Kitade yearned to uncover the seven passengers’ names and fates. He started digging. He spoke with an Israeli diplomat posted to Tokyo and interviewed people in Tsuruga and in Kobe, a city to which many refugees continued.

Like Sugihara, Kitade couldn’t succeed alone.

One who helped him was Matsudo resident Kiyotaka Fukushima, who’d been fascinated by Jews since meeting an Israeli woman in nearby Tokyo in 1999. An October 2011 newspaper article on Kitade’s search caught Fukushima’s eye. Three years later, a TV feature brought news of Kitade’s having identified the first of the seven passengers, Zosia Gertler. That occurred after a Japanese-Canadian woman and Sugihara admirer named Aya Takahashi saw the Osako photographs that Yad Vashem had posted. She contacted a Montreal woman, whose cousin in New York identified Gertler as her late mother, a native of Lodz, Poland.

Fukushima arranged to see Kitade in April 2015 in Tokyo, where Kitade presented his just-published book about the search, Visas of Life and the Epic Journey: How the Sugihara Survivors Reached Japan.

Fukushima mined the book for clues. Within a month, he’d compiled whatever could be gleaned of the six other missing people and wrote to the International Tracing Service, in Bad Arolson, Germany, which Fukushima knew about from an article he’d once read. His query yielded success with the ITS: a list of passengers who’d boarded the U.S.S. General Gordon in Japan on March 24, 1949, bound for San Francisco. The first page listed 29 passengers, all residing in Shanghai, all presumably refugees. Near the top was one named Antonina Altszuler. On the back of the photograph she’d given Osako, Altszuler’s name appeared as “Altschu”—the last three letters probably ripping off when Kitade removed the photograph from the album’s page. That was in 2009, six years after Osako died, when his daughter retrieved the fragile album with the blue cover and loaned it to Kitade.

Fukushima shared his findings with Mark Halpern, a Pennsylvanian he had met briefly in 2013 in Boston, when Fukushima, then working in the aviation industry, was in the area on business. Their encounter occurred in an unlikely place: the annual conference of the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies. Halpern sought out Fukushima after scanning the registration list and wondering about the Japanese man attending.

Fukushima unearthing the General Gordon manifest turned out to be “Ground Zero” in identifying Altszuler, Halpern said. He would learn that she was born in 1919 in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska, Poland. Altszuler was aboard the Amakusa-maru on March 22, 1941, the date she inscribed on the picture, then lived in Kobe for about three weeks (receiving aid from the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee) before moving on to Shanghai.

From San Francisco, Altszuler traveled to Illinois, met and married a U.S. Army officer, Wallace Babb, returned cross-country and worked for 32 years as a University of California, Los Angeles, librarian. She died, childless, in 1994, bequeathing her entire estate of $592,000 to UCLA’s Holocaust-studies department.

“Without him,” Halpern said of Fukushima, identifying Altszuler “wouldn’t have happened.”

Of the five refugees Kitade’s ad-hoc team has identified, the male passenger was determined to be Nissim Segaloff, a Bulgarian Jew who settled in New York and changed his name to Nicholas Sargent, but for whom no death record was found. One Jewish woman, also from Bulgaria, got married in America, bore three children, and died in 2005, but her family requests anonymity. Only Zosia Gertler appears on a list Halpern viewed of Sugihara-issued transit-visa recipients.

***

Harrang, Birnbach’s mother, wasn’t a “Sugihara Jew,” or Jewish at all. She was a Lutheran, born in 1917 in the Norwegian city of Drammen.

When the Nazis occupied Norway beginning in April 1940, Harrang was in her early 20s and possessed of stunning beauty. Her mother, Emma Johanson, was terrified by the Nazis’ kidnapping of desirable women for their Lebensborn program of breeding a master race of Aryans. She sent Harrang to live with relatives in Johanson’s native Sweden. What Johanson didn’t know was that Harrang already endangered herself by working in the Norwegian underground.

In Sweden, Birnbach told the Japanese television crew, Harrang’s passage to Vladivostok, Tsuruga, and on to America was arranged by Emil Kronberg, a married Jewish businessman from Vienna with whom she’d been having an affair. Harrang “was secretive” and never discussed the journey, Birnbach said.

Birnbach has filled in some blanks since Halpern found her last October. She speculates at her mother’s fondness for Osako and his colleagues. On the picture back, above her signature, Harrang had written in Norwegian, “To the nice Japanese person: Remember me.”

“It was brave of them,” Birnbach said of the ship’s crew. “They … are heroes, particularly for the fact that Japan and Germany were allies. They risked their lives to help other people.”

Escaping eastward “was the only way out for a lot of people. It’s remarkable that she was able to get out, my father was able to get out—even more so because he was a Jew,” she said of Kronberg, whom Harrang married, after he got divorced, in 1942, seven years before Birnbach was born. “I wouldn’t be here if they didn’t get out. That’s the story of so many survivors.”

Birnbach was asked to pose with a white-framed photograph of her mother. The interviewer wondered what she’d tell Harrang now.

“I’d thank her for being brave, for bringing me up the right way and allowing me to respect all kinds of people, whether Jewish or not Jewish. Even though she was not Jewish and it sometimes was difficult for her to be accepted into my father’s family, she made the best of it. I was brought up not in a religious home but in a house that respected tradition.” Birnbach dabbed at her eyes. “I wish she was still here,” she said.

Kitade, Halpern, and Fukushima continue to investigate the identities of the two still-unidentified women among the seven: one who wrote in French, “With all my affection. Marie,” and the other, who wrote in Polish, “Remember me,” but didn’t sign it.

Osako’s family has donated the album page to Tsuruga. It will be displayed in the city’s aptly named museum: Port of Humanity.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Hillel Kuttler, a writer and editor, can be reached at [email protected].